His name was Vít Fučík and he was born on June 3, 1733, in Vitějovice, and died on November 29, 1804, in Klůs near Strpí. He is known as the First Czech Aviator. Vít Fučík engaged in aerial experiments by attaching wings he crafted himself. According to the existing literature, he conducted a total of four flights to Vodňany and one to Selibov, all originating from his cottage in Klůs between 1760 and 1770.

Many, many, many years ago, a man named Vít Fučík lived in solitude at “Klůs,” near the nearby forest of the same name, in the former Libějice estate. The local people referred to him as “Kudlička.” He spontaneously learned carpentry and carving, and because he was persistently cutting twigs as a young shepherd, he earned the nickname “Kudlička.” When he reached about 50 years old, he made wings for himself, attached them to his body, climbed onto the roof of his cottage, spread his wings, and launched himself into the air.

They say that Vít Fučík flew. They called him the Birdman, the Messenger of the Skies, the Czech Icarus, the Golden Bird, the Heretic on Wings, and the First Czech Aviator…

He flew, and when he flew over a pond, he couldn’t endure the lack of air, so he had to land on the edge of the pond to avoid drowning.

Could it be a reality that a humble individual from an isolated cottage took flight like a bird? Is it conceivable that this individual achieved soaring heights even before the renowned aviators who are globally recognized? If this is indeed the case, what became of this groundbreaking invention? Furthermore, what drives the ongoing quest of those who tirelessly seek to uncover the secrets behind this invention?

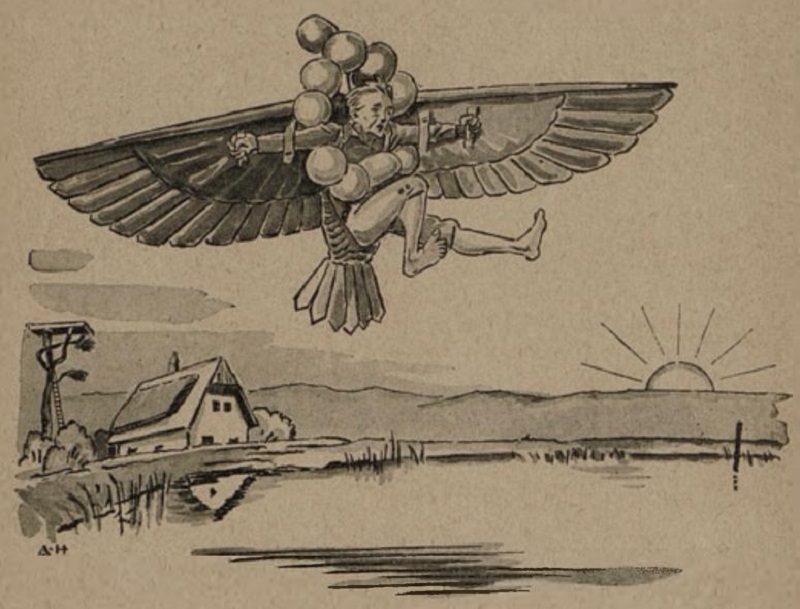

Illustration of Vít Fučík from: Z dějin naši vzduchoplavby.

“He leaned down even more and started running. His leaps were progressively longer and lighter. He’s already beyond the edge of limits. The final push-off. He holds the wings with all his might. Veins are pulsing in his neck, his hands stiff with cramp. Beneath him, he feels emptiness. He’s flying!”

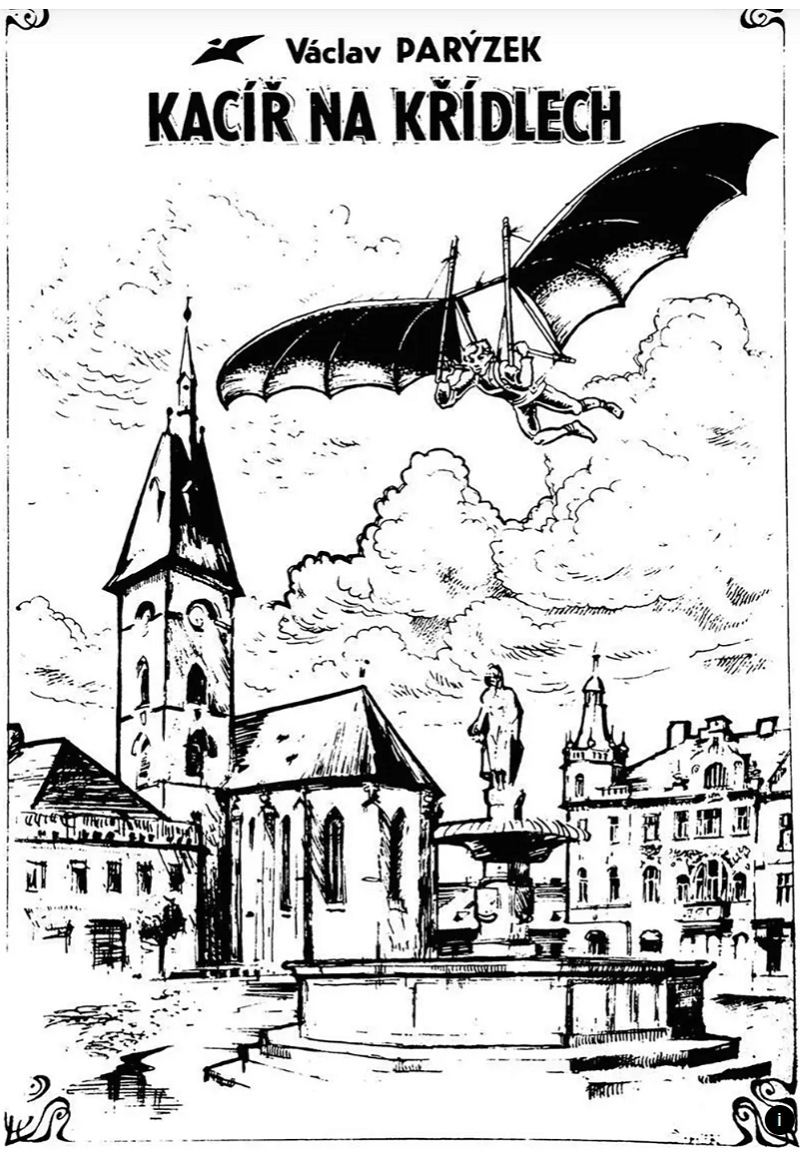

This is how writer Václav Parýzek envisioned the overcoming of earthly gravity by the first human in his novel “Kacíř na křídlech” (Heretic on Wings). In it, he describes the life of Vít Fučík, a South Bohemian serf, who supposedly ascended several months, perhaps even years, before November 21, 1783, when the Montgolfier brothers launched the first balloon with a human crew in Paris.

Did he really fly or not?

Indeed, he flew…

During the summer of 1920, Captain Antonín Mašek, serving in the Prague Air Corps, spent his vacation in Týn nad Vltavou. He heard of a local aviator and grew intrigued: What if he truly flew before the Montgolfier brothers? Enthusiastic Captain Mašek, with the help of local district governor Anton Böhm, delved into the investigation. He questioned witnesses, visited the solitude near the village of Strpí where Fučík lived, and even spoke with his great-grandson.

He fastened the wings with a leather harness. On it, he attached pig bladders filled with marsh gas, which lifted him.

“My great-grandfather, named Fučík, from whom I am the descendant of the fifth generation, according to accounts preserved in our family, indeed flew. His aircraft consisted of massive metal wings, connected to a special suit sewn entirely from large bladders. He moved the wings using his hands… he took off either from a pond dam located about 50 steps from the house or from a sturdy pine tree adapted for this purpose and located not far from the dwelling,” recounted seventy-five-year-old Strpí local Josef Straka.

Fučík’s Wings

He drilled holes into the metal frame of the wings and attached goose feathers in them. He then connected the wings with a leather harness, a sort of yoke. Onto this harness, he affixed pig bladders filled with marsh gas from the surrounding wetlands, which lifted him.

The Ministry of Defense Investigates

“Considering this information to be quite important, I hereby notify the command of the aviation department and kindly request that, in coordination with the 13th division, further steps be taken to investigate the matter. I emphasize that Fučík would have preceded the invention of the balloon by twenty years, the French Montgolfier brothers, and by 150 years the first aircraft designers altogether,” wrote Mašek in a letter addressed to the Ministry of National Defense. Major Václav Rypl took charge of the initiative, and the ministry, in collaboration with the Military History Institute, launched an extensive investigation.

Even more stories circulated among the people. Small Vít reportedly weighed barely fifty kilograms, but he was a diligent worker, skillful carver, joiner, and mechanic. He earned the nickname “Kudlička” because he always carried a small knife with him, and he was often seen deftly crafting pieces of wood with it.

“My wife Aloisie Pytlíková, nee Skalická, informed me that her great-grandfather Jan Skalický, who was the mayor of Vodňany from 1823 to 1837, told her (the children) that a certain cobbler from Strpá flew over Strpá Pond with wings he had made himself, and that a large number of people from the town of Vodňany witnessed the flight,” said Josef Pytlík, the director of the school in Vodňany, to Rypl.

Messenger of the Skies

The legends about the flying of the “citizen of Strpá” were confirmed by several long-time residents. They also provided various details passed down orally through their families. As Václav Rypl writes in his book “From the History of Our Aviation,” Kudlička allegedly first took flight from his cottage above the nearby Strpá Pond, but he “couldn’t catch his breath and had to land on the ground at the edge of the pond to avoid drowning.”

Over time, he improved his wings to the point where he could fly to the town of Vodňany, which was up to five kilometers away. Local resident Izák Arnšteiner, a Jewish man, recalled from his childhood the story of a man who, on the eve of Sabbath, September 19, 1783, emergency-landed on the window of the Vodňany synagogue.

“The Messenger from Heaven” startled the present believers. Eventually, the conviction prevailed that they were witnessing the arrival of the anticipated Messiah, and they generously rewarded him. From then on, his friends nicknamed him the “Golden Bird”…

“If God wanted humans to fly, He would give them wings!” And so, the joiner cut up his wings and crafted crucifixes from them.

However, occasionally, the wings failed. When Kudlička attempted to fly all the way to Písek, the gas from the bladders leaked out on the way, and he had to make an emergency landing near the village of Selibovo. During another flight to Vodňany, he was caught by a storm on the dam of the Černoháj Pond. “Here, he fell onto a large stone on the dam and was seriously injured in the chest. He probably broke bones and completely stopped flying,” recounted his great-grandson Josef.

The aviator took a long time to heal from the injuries sustained. The parish priest of the Church of St. Stephen on Bílá Hůrka also rebuked him thoroughly for tempting God: “If God wanted humans to fly, He would give them wings!” And so, the joiner cut up his wings, made crucifixes out of them, and hung them on the surrounding trees as a sign of repentance… But he didn’t stop dreaming.

Facing Trial for Heresy

“Noble, honorable, and learned gentlemen, dear friends and acquaintances!” begins the letter from Lorenz von Gamsenberg, the Prácheň region’s governor, addressed to the Písek council on August 12, 1780. He requests that Josef Riedl and Jiří Kozlík from Vodňany, Josef Štika, Vojtěch Krump, and Vít Fučík from the estate of Libějovice be brought before the Písek court of justice due to “their involvement in prayers to St. Crown or St. Christopher.”

The phrase “to pray to St. Christopher” could be interpreted as a euphemistic term for witchcraft or heresy. “There were rumors about Fučík that he could fly using a special contraption. Such a thing could, of course, only be possible with the help of supernatural beings,” suggests Jan Bauer in his book Bílá místa českých dějin (Blank Spots in Czech History).

However, there is a simpler explanation. St. Christopher and St. Corona (or St. Crown, also known as St. Corona, a martyr from the 2nd century) were popular patrons of treasure seekers. The forbidden “prayers,” or rather incantations, were meant to assist people in searching for hidden wealth in the ground. It’s possible that Kudlička, bored after the forced end of his aviation experiments, found a less dangerous hobby…

Whether one way or another, it’s certain that the ominous-sounding accusations did not end tragically. A hundred years had passed since the era of the Inquisition’s tribunals. Times had changed. During the Enlightenment reforms, similar magic was considered more of an attempt at fraud than heresy. As a result, the joiner could quietly spend almost another quarter of a century in his solitude in Klůs.

Introduction

On August 12, 1780, an intriguing summons arrived in the historic town of Vodňany, marking the beginning of a story that would transcend time and capture the imagination of generations. The accused were linked to forbidden prayers to St. Koruna and Kristof, and among them was a name that would become synonymous with innovation, daring, and a relentless pursuit of dreams – Vít Fučík.

Unveiling the Legend

Nestled within the careful confines of the Vodňa Museum, the original document of that summons still exists, preserving a fragment of history that speaks volumes about the accused and their forgotten stories. Although the details of most accused from the Libějovice estate have faded from regional history, Vít Fučík’s legacy remains alive. Over 200 years later, he remains one of the most renowned personalities of Vodňany.

The First Czech Aviator

Despite the relentless efforts of historians, including those with military expertise, Vít Fučík is widely regarded as the first Czech aviator. In the years spanning 1760 to 1790, he embarked on an extraordinary journey fueled by a fascination with birds’ flight. Inspired by nature’s design, he constructed wings for himself, which allowed him to soar through the skies. His experimentation wasn’t limited to the vicinity of his cottage in Klůs; he ventured over Strpský pond and even made a memorable landing near the Vodňany synagogue, much to the amazement of the local Jewish community.

An Enduring Legacy

Vít Fučík’s legacy extended far beyond the reach of his flights. The skilled carpenter’s life inspired countless individuals, and his tale resonated with writers, journalists, and screenwriters who sought to capture his legendary courage and determination. Despite the passage of time, his story continues to serve as a timeless reminder of the power of ambition and the pursuit of seemingly unattainable goals.

Innovation and Resilience

As we revisit the pages of history, the name Vít Fučík shines as a beacon of innovation and resilience. His early endeavors into flight, driven by craftsmanship and boundless dreams, remain a testament to the human spirit’s unyielding desire to conquer new frontiers. While his physical flights might have ended, his legacy continues to inspire generations, reminding us that even in the face of uncertainty, with unwavering determination, we can reach for the skies and beyond.

Was Vít Fučík the Czech Icarus?

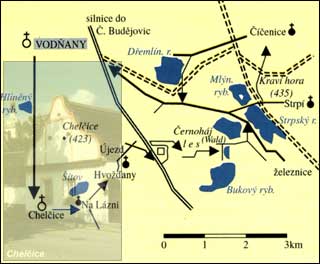

Route: Vodňany – Chelčice – Na Lázni – Hvožďany – Újezd – Černoháj Forest – Strpí – Číčenice – Dřemlín Pond – Vodňany Total Circuit Length: 18 km. (Vodňany Tour for Vít Fučík)

In the circuit to the south and east of Vodňany, we come across the early Baroque hexagonal chapel of St. Mary Magdalene from 1660-3 and the former spa near Chelčice. Through Hvožďany and the Černoháj Forest, we reach the place where Vít Fučík, nicknamed Kudlička, conducted his flying experiments. He lived in the latter half of the 18th century in the solitude of Klůs, which falls under the village of Strpí. A skilled craftsman – carpenter and carver – with a good reputation throughout the Vodňany region, he is said to have flown long before the Montgolfier brothers conquered the skies with their balloons. M. Veselý wrote an interesting short story about him called “Bird Man” based on oral traditions passed down through several generations.

A brief excerpt from it gives us a certain picture of Vít Fučík’s flying: “Once he attached those bladders (supposedly from pigs), which he filled with gas from the surrounding ponds (marsh gas, chemical formula CH4), around his body, dressed in a suit with wings, and against the western wind, towards Vodňany, he jumped from the attic window into the air. With strong, well-developed craftsman’s arms, he waved like a bird. He fairly successfully flew over the nearby Strp Pond… In due time, he ventured towards Vodňany, and even aimed to reach the market in Písek, but only made it to Selibov. After his fourth flight to Vodňany, he fell on the dam of Černoháj. He broke his ribs.” What the reality was, whether it was different, we will probably never know. Let’s at least keep the romantic notion.

Golden Bird or Heretic on Wings

The following is my translation of a document by Bohuslav Trnka entitled Zlatý ptáček, nebo kacíř na křídlech? (Golden Bird or Heretic on Wings?) from February 14, 2012.

Technological discoveries in the past often made slow progress, sometimes only gaining popularity in specific regions or countries, and sometimes falling into oblivion until later epochs brought them to the world’s attention or reinvented them. This was also the case with the beginnings of flying in South Bohemia, where this history is intertwined with the name of Vít Fučík – Kudlička for over two centuries.

The thorough investigation was carried out mainly by Captain Ing. Antonín Mašek, a member of the aviation corps in Prague. In close cooperation with District Captain Dr. Anton Böhm from Týn nad Vltavou, he explored the given location, acquainted himself with and talked to witnesses and descendants of the Fučík family. From them, he obtained numerous interesting, albeit sometimes conflicting, pieces of information. Among the results was the discovery that the first aviator in South Bohemia undertook a total of five flights between the years 1760-1770 from the Klůs homestead near the village of Strpí. Four of these flights were to the nearby town of Vodňany, and one was directed towards Písek, interrupted near the village of Selibov near Tálínský Pond. During one of the flights to Vodňany, he allegedly landed near the local Jewish synagogue, which caused a tremendous commotion among the present worshippers and quickly led to the general belief that the awaited Messiah had arrived. He was generously rewarded and from then on, the folk epithet “Golden Bird” was added to his nickname “Kudlička.”

Captain Mašek further discovered that Fučík was a skilled carver, carpenter, and mechanic. The only aspect in which the mentioned researcher was probably mistaken, as witness testimonies suggest, was the use of bladders filled with marsh gas, which were supposed to lift the aviator’s body during flight. Similar misconceptions accompanied many naturalists for years, yet a simple mathematical calculation could have revealed the necessary buoyancy, yielding a clear result. Moreover, the technical equipment for capturing marsh gas and injecting it into bladders was hardly conceivable in that era.

In 1920, Captain Mašek formally submitted the conclusions of all his research and inquiries to the 13th Aviation Department of the Ministry of National Defense in Prague, recommending further investigation. This was based on the potential confirmation of all the information about Fučík, which would mean surpassing the precedence of French balloonists P. de Rozier and d’Arlandes. They achieved the first ascent using a hot air balloon (montgolfière) on November 21, 1783.

Following Captain Mašek, another aviator, Major Václav Rypl, took up the task of tracing the footsteps of Fučík under the initiative of the Ministry of National Defense. During the years 1922-1926, he focused on studying available source materials, corresponding with witnesses, and utilizing archival and registry records. He succeeded in verifying the accurate date of Fučík’s death in 1804 according to the death register of the parish office at the Church of St. Stephen in Bílá Hůrka, where Fučík was laid to rest in the local cemetery.

Although subsequent acquired materials did not immediately confirm Fučík’s flights, V. Rypl compiled a preliminary study on this case, complementing it with biographies of other aviation pioneers. This effort resulted in one of the earliest works on the history of Czechoslovak aviation, published as a book in 1927 under the title “Z dějin naši vzduchoplavby” (From the History of Our Aviation). Since then, numerous newspapers and magazines have explored similar themes, and there’s hardly a domestic aviation history reference that doesn’t mention Vít Fučík and his flying apparatuses.

A more comprehensive material, presented in the form of a biographical narrative, was the samizdat publication by Václav Parýzek, aptly titled “Heretic on Wings” (Vodňany 1988). The author synthesizes his long-standing research and inquiry, drawing from documents at the State Regional Archive in Třeboň, notes from Ing. J. Raab, memories of the Vodňany chronicler M. Veselý, articles by Ing. Mašek, Maj. Rypl, Dr. Böhm, and writings from the former branch of Masaryk’s Aeronautical League in Vodňany. Based on these sources, he attempts to outline the tumultuous life stories of the South Bohemian aviation pioneer and substantiate his actual existence until his death in 1804.

Aside from several authentic records, the photocopied summons to the appellate court in Písek is particularly intriguing, preserved in the Vodňany museum and dated August 17, 1780, with the following text (adjusted):

“To the most respected, noble, honorable, and learned, especially dear gentlemen and friends. Since the illustrious Royal Appellate Chamber on the 18th of the previous month of July discovered and today announced that, through established investigation into participation in prayers to St. Crown or Christopher, some are accused and others found complicit, namely Josef Riedl and Jiří Kožlík from Vodňany, not less so Josef Štika, Vojtěch Krump, and Vít Fučík from the Libějovice estate, they are to be once again brought before the capital city court in Písek for a criminal trial. Let the magistracy not fail to have these individuals brought here to be handed over to the aforementioned criminal court early in the morning of the 17th of this month… Regional governor appointed by the Imperial Roman Emperor and King, Lorenz I. von Gamsenberg of the Prácheň region.” The outcome of the process and any potential punishments are not yet known, but it is certain that this transpired shortly before the official accession of Emperor Joseph II, on the eve of an era later termed the Industrial Revolution. Indeed, the second half of the 18th century is significantly marked by profound changes in the realms of thought, politics, economy, and culture, reflecting this reality through significant inventions of its time.

But let’s return for a moment to the documents in the Aeronautical Archive of the South Bohemian Museum in České Budějovice. From the manuscript of Dr. Böhm’s council, discovered by archivist R. Šerý in the former Hausrova printing house in Týn nad Vltavou, we encounter additional passages that, from today’s perspective, bring forth intriguing comparisons related to the Fučík case, corresponding to the conclusions at hand: “When (Fučík) grew old, relatives, sons-in-law Vavřinec Straka and Matěj Hraba, following his instructions, constructed a new apparatus that was used for flying by the sons of Schwarzenberg officials from Libějovice. This time, they attached the aircraft with a rope to prevent it from flying too far away … The damaged wing parts were stored in the attic of the Klůs homestead until 1860, when a learned gentleman from Prague came and took them away…”

From this citation, one might deduce that Fučík’s third design took the form of a kite-like suspended glider, which, in stronger winds, could remain airborne by being tethered or held by assistants, and upon release, would glide down to the ground with the pilot. Examples of this hypothesis can be found not only in ancient history (the use of kites in China with an observer to monitor enemy incursions, 13th – 14th century) but also in the early 20th century.

Before the First World War, South Bohemian modelers, in collaboration with their colleagues from Prague, attempted the construction of lightweight suspended gliders (weighing between 14 to 40 kg), inspired by the example of German glider Otto Lilienthal, who conducted over 2000 test flights with suspended gliders between 1891 and 1896. These gliders, flown against the wind from slopes, covered distances of up to 200 meters and remained in the air for 10 to 12 minutes. It’s worth mentioning Czech-Budweis structural engineer V. Verner with his “Lili,” and F. Šíp from Vimperk with the “Šumava” glider. All of them essentially built upon Fučík’s design concepts for heavier-than-air aircraft, refined through the experiences of Lilienthal.

A marginal note in the manuscript mentioning that around 1860 a learned gentleman from Prague took away remnants of Fučík’s glider’s wings could pertain to K. V. Zenger (1830-1908), a professor at Prague’s Polytechnic and a pioneer in applied physics, particularly in the fields of airflow and meteorology. The fact that the first mentions of Fučík appeared in Prague’s press the following year, 1861, leads to the speculation that perhaps one of the few direct proofs of the existence of the South Bohemian glider ended up in university archives (the collection of the Royal Czech Society of Sciences). It’s possible that parts of Fučík’s wings served as prototypes for other aviation pioneers. Identical design elements could then directly point to the project of the well-known but unsuccessful Czech aircraft, Kadeřávek’s “mávavý křídla” (flapping wings) airplane (1866), human-powered and designed to flap its wings. V. Kadeřávek (1835-1881) was an assistant and mechanic at Prague’s Polytechnic.

The publisher of the “Myslivecké zábavy” (Hunting Amusements) magazine in Prague, a former Schwarzenberg forester, was the first to unveil the veil of mystery surrounding the unknown South Bohemian Icarus when, in the aforementioned year of 1861, he published his private investigations as follows:

“My father, Václav Špatný, 85 years old, residing in Skočice near Vodňany, told me that many years ago, a man named Vít Fučík lived on the solitary Klůs, so named after the nearby forest, on the former Libějovice estate. The local people called him Kudlička.”

He learned carpentry and carving on his own, and because as a young shepherd, he was often seen carving with a small knife, he was given the nickname “Kudlička.” When he was around 50 years old, he made wings for himself, tied them on, and climbed onto the roof of his cottage. Then he spread his wings and took to the air.”

His profession as a carpenter, former shepherd, assistant forestry worker, and later a gamekeeper is confirmed by various records of debts from his estate proceedings. For instance, the village of Malovice owed Fučík – Kudlička payment for delivering wooden statues of Saint John, Saint Vojtěch, and Saint Florian.

Although Vít Fučík, also known as Kudlička, lived to a considerable age, he didn’t advance further in aviation after his initial attempts. His name is just the beginning of the long journey of others in the field: experts in aerodynamics, who were theoretically preparing for the glorious era of domestic aviation – such as ing. G. Finger, dr. F. O. Vaňek, ing. J. Trunečka, and many others. So, while the honor of the first human ascent in a balloon is attributed to the French, and the glider flights to the Germans and Otto Lilienthal, let the simple cottage-dweller Vít Fučík have his honorable place among them.

Source: Catalog Ceskoslovenske zapalkove nalepky 1961-1963 by Jiri Sperk

Evidence

“Flying would have left traces in official reports or church records,” notes Jiří Dufek, a FAMU professor preparing a book about the South Bohemian aviator.

This aligns with the opinion of the former head archivist of the Schwarzenberg Archive, Antonín Markus, who wrote in 1922, “I believe that Fučík perhaps wanted to fly and constructed some kind of aircraft, conducted experiments – naturally with no success – and injured himself in the process. If he truly managed flights to Vodňany, Písek, etc., I consider it unlikely that our archives wouldn’t have preserved anything about it.”

For a human to be lifted by wings, they would need a wingspan of 15 meters and a wing area of about 20 square meters.

Furthermore, the laws of physics work against Kudlička. Swamp gas methane (CH4), also known as the “souls of the drowned,” is lighter than air, but… As calculated by engineer Jan M. Raab in 1940, methane has a lift capacity of 0.57 kilograms per cubic meter. This means that Vít Fučík would need nearly 20,000 bladders to lift himself. However, this would only work if they didn’t weigh anything. With an average weight of 55 grams each, a bladder filled with methane wouldn’t even lift itself. Thus, air travel is not feasible.

Human strength alone simply isn’t enough for takeoff. Wings powered by flapping arms would need a wingspan of 15 meters and a wing area of about 20 square meters, according to Raab’s calculations. And for flying with such wings, the human skeleton would have to be arranged similarly to that of a bird: huge, disproportionately developed upper limbs and atrophied lower limbs. Additionally, the bones would need to be hollow for lightness.

But what about a hang glider? In the Vodňany region, winds usually blow from west to east, and Vodňany is east of Klůs. Could the joiner have lifted against the wind, which, in combination with low weight, enabled gliding?

Bohuslav Trnka, the author of the book “Zlatý ptáček, nebo kacíř na křídlech” (Golden Bird or Heretic on Wings), believes that might be the case. He writes, “The construction resembled a kite-like hang glider that could sustain itself in the air during stronger winds, anchored or held by assistants, and after release, glided to the ground with the pilot.”

This hypothesis could be supported by the manuscript of Anton Böhm, preserved in the Aviation Archive of the South Bohemian Museum in České Budějovice. “When (Fučík) grew older, his relatives, sons-in-law Vavřinec Straka and Matěj Hraba, constructed a new machine according to his instructions. This time, they tied the aircraft with a rope to prevent it from flying too far,” it reads.

Supposedly, officials from Schwarzenberg’s administration in Libějovice witnessed the attempt, as well as, according to Mr. Straka, “some professors from Prague.” Allegedly, the son of one of the officials managed to take off, but shortly after, he crashed and destroyed the wings.

“In the flat landscape between the ponds, even today’s hang glider pilots wouldn’t be able to glide, except perhaps if they were towed by a car,” adds Jiří Dufek. He supports this with a record in Reitinger’s chronicle from the 19th century.

According to him, in 1820, a group of young men from Vodňany collected “forty golden guilders from their fathers, purchased steel springs, goose feathers, bladders, ropes, and dyed canvas,” and in the hope of getting rich by demonstrating flying, they went to see the cottager named Kudlička (who must have been his son-in-law or grandson, as Vít had been dead for sixteen years). This Kudlička had previously attempted flying and fell into a pond. With their knowledge, they intended to correct his mistakes, built wings, and one of them jumped from the ground, dislocating his arm from his shoulder.” That was the end of their attempts at flying.

Could we at least find the damaged Kudlička’s wings? Allegedly, the remains of the wings lay in the attic of the Klůs homestead for many years. According to Josef Straka’s account, around 1860, “a learned man from Prague came and took them with him.” This mention could refer to Václav Kadeřávek, an assistant at the Prague Polytechnic, or his superior, Professor Václav Zenger of the Czech Polytechnic Institute.

In the 1860s, Kadeřávek constructed a model of an ornithopter, an aircraft with flapping wings. He optimistically named it the “Czech Airplane.” “With this aircraft, he indeed made two attempts, the first in the courtyard of the Voštěp Brewery, whose brewmaster, Mr. Jednorožec, was among his foremost supporters, and the second in the presence of several friends on the Letná plain in Prague. The apparatus moved in a manner similar to a bird that, mortally wounded, tries in vain to escape its pursuers, but it did not rise to any significant height,” describes Ottův slovník naučný (Ott’s Encyclopedic Dictionary) under the entry for “Samolet” (Airplane).

Did perhaps the young assistant from the polytechnic get inspired by Kudlička’s wings? In that case, we might find them in one of the museum storage facilities! “I’ve gone through the entire catalog of the polytechnic institute, but unfortunately, I didn’t come across any ‘samolet’ or Václav Kadeřávek. There are only documents related to Václav Zenger’s professional career,” Kamil Mádrová from the Czech Technical University Archive told Magazín.

We had a similar outcome at the National Technical Museum Archive. “I tried to search the records of acquisitions for the collections of the National Museum and at the Ohrada Castle near Hluboká, where Prince Schwarzenberg established a hunting museum in 1842 that still exists today, but in vain,” concludes Jiří Dufek.

Is it a pity for the beautiful dream? Not at all! While it took another hundred years for the German Karl Lilienthal to successfully take off with controllable gliders, dreamer Kudlička didn’t risk unnecessarily. With his broken ribs, he showed the dead-end path in the development of aviation. Thanks to him, through trial and error, humanity eventually reached the airplane heavier than air.

Fučík’s Lineage

The lineage of Vít Fučík originated from the village of Hracholusky on the Libějovice estate. After the Thirty Years’ War, Jiří Fučík managed one of the local mills, followed by Jan and then Šimon Fučík. Although the kinship ties among them are not unequivocal in light of the sources, the agnate line can be reliably traced from Šimon onwards. This Šimon was the great-grandfather of Vít Fučík, known as Kudlička. With his wife Anna, he had children Ondřej (~ November 23, 1669), Matěj (~ February 7, 1671), and Mariana (~ May 14, 1673), all born in Hracholusky. He passed away before the year 1700, and his widow between the years 1715-1719.

Andřej, the elder of Šimon’s sons, was mentally disabled, remained single, and lived with his brother Matěj, who took over the farm. On November 1, 1695, Matěj Fučík married Dorota, the surviving daughter of Lukáš Havrda from Šipoun. From this marriage, children were born: Marianna (*circa 1696), Václav (*circa 1698, † 1699), Jakub (*1700), Žofie (*1702, † 1705), Pavel (*1705, † 1709), Vít (*1707), Václav (*1709), Jan (*1712), Vavřinec (*1714)7, and František († 1720). Their father Matěj lived to be 63 years old and passed away in Hracholusky on August 3, 1734, while his wife Dorota died there on November 20, 1742.

The homestead in Hracholusky was inherited by their son Vít. His younger brother Jan (~ May 29, 1712) married Marianna Koptová in Vitějovice on November 24, 1732. They initially lived as tenants in Vitějovice, where their firstborn Vít was born on June 3, 1733. He later became renowned for his aviation attempts. Following him were Ondřej (*1734, † 1735), Pavel (*1736, † 1736), Bartoloměj (*1737, † 1737), Lucie (*1738), Kateřina (*1741, † 1742), and Matěj (1743). All these children were born in Vitějovice.11 In 1749, Jan Fučík took over a homestead in Velký Bor worth 63 Meissen groschen from Vít Havlíček. Since Vít Havlíček was unable to manage further, he willingly transferred it as compensation. Jan Fučík collected fees from the villagers between 1750 and 1758, but due to debts, he could no longer manage. Therefore, in 1760, he passed the business to Jakub Faktor, the husband of his daughter Lucie. Jan Fučík became a widower on February 25, 1767, and on April 9, 1769, his youngest son Matěj passed away in Bor, and Jan himself died the following day.”

Over Time Researchers Verified Facts

- Vít Fučík was born on June 3, 1733, in Vitějovice.

- He began as a shepherd and a helper in forestry work, and later worked as a gamekeeper.

- He bought a cottage in Klůs.

- He died on October 29, 1804, at the age of 71, from tuberculosis

- He was buried at the cemetery near St. Stephen’s Church on Bílá Hůrka.

Exploring Fučík’s Terrain

The excursion route traverses a flat landscape, along the embankments of smaller and larger ponds such as Strp and Dřemlín. Their glistening surfaces add charm and color to this part of the Vodňany region.

Route Description

Map From Vodňany, we start from the bus station, Zeyer Gardens, following the blue hiking trail – heading south – to Chelčice, which is about 3.5 km away. Also, cycling route no. 1099 leads there. From Chelčice, starting at the crossroads, we continue along the blue markers to the church. In front of it, we can see a barn with sundials and then follow the road from roadside crosses to a field path leading to the hexagonal chapel of St. Mary Magdalene, originally early Baroque, from 1660-3. From there, we head to the Na Lázni buildings. Here, we leave the blue trail and walk straight along a field path past a cross to the road on the outskirts of Hvožďany. Eventually, we arrive at the square, and after passing a little chapel, we turn left and continue straight along the road to Újezd, where we turn right at the intersection. After the village, the original road ends. We then follow an approximately 100 m stretch alongside the new road (to České Budějovice) to a spot where we can cross to the other side. We follow the asphalt road back, passing by the mill. After about 300 m, we turn right onto a field path heading towards the Černoháj Forest (0.8 km stretch). At the beginning of the forest, we continue straight along its edge (with Bukový Pond on the right, otherwise Lukavec). Afterward, a less distinct path turns left, then about 300 m to the right (past a cross from 1884) – until we reach a junction in front of a small pond. We continue along the forest path on the left and after about 150 m, at the next crossroads, we turn right. Exiting the forest, we turn left onto the paved road and, after around 300 m, we arrive at a bus stop near the village of Strpí. The road follows a lovely section along the dams of ponds. After the railway, we reach a crossroads, where a small road (ideal for cyclists) under Kraví Hora Hill leads to Číčenice in less than 2 km. If we visit Strpí, we’ll see a chapel from 1833, and from the road, we’ll have a beautiful view of the ponds and wooded hills on the horizon. In Číčenice, we turn right on the road to see the square with an interesting chapel before returning to Vodňany on the left side. After about 0.7 km past the village, we turn left onto a road along the dam of Dřemlín Pond, leading to the road from Dívčice (Radomilice) to Vodňany. On the right, we’ll see the dominant tower of the Vodňany church, with the last 2 km of comfortable walking ahead. This road also follows cycling route no. 1080.

In Literature

Book 1) Ladislav Stehlík recalled Vít Fučík’s character and life experiences, including his flight experiments, in his work Země zamyšlená (The Contemplative Land).

Book 2) The story of this aviator from the 18th century is also mentioned in Jiří Hajíček’s novel Dešťová hůl (Rain Stick).

YOU Can Help Bring His Story to English Readers

Book 3) There is also a book entitled Z dějin naši vzduchoplavby (From the History of Our Aviation) by Václav Rypl written and published in 1927, which I NEED YOUR SUPPORT TO TRANSLATE.

Every year, through our Czech Revival Publishing, we reach out to a select group of donors and sponsors who share our passion for introducing new Czech and Czech-themed literature to English-speaking audiences. We invite contributions to support the creation of fresh literary works in various genres, including fiction, literary prose, poetry, drama, memoirs, literary non-fiction, children’s and young adult literature, journalism, essays, biography, and history.

This book will primarily delight enthusiasts of the history of conquering the blue sky, as it delves into all the successful and unsuccessful, well-documented and less-documented attempts at human flight, whether in balloons or on wings. The book also includes many interesting photographs and drawings.

If you have a passion for aviation or a keen interest in history and would like to contribute to the publication of this book through a translation grant, you have the opportunity to do so by visiting this link.

In appreciation of the donor’s invaluable support, we intend to prominently feature their acknowledgment in the book itself, as well as in all marketing and promotional materials. The specific wording and placement of this acknowledgment will be collaboratively determined by the publisher and the donor or sponsor, ensuring alignment with the book’s design and prior to initiating the book’s marketing campaign. You have the opportunity to contribute by making a donation in your name, the name of a loved one, or even in the name of your business.

Your contribution makes the translation of this book possible. Click here to support the publication of this book as a donor/grantor.

Post sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8.

We tirelessly gather and curate valuable information that could take you hours, days, or even months to find elsewhere. Our mission is to simplify your access to the best of our heritage. If you appreciate our efforts, please consider making a donation to support the operational costs of this site.

You can also send cash, checks, money orders, or support by buying Kytka’s books.

Your contribution sustains us and allows us to continue sharing our rich cultural heritage.

Remember, your donations are our lifeline.

If you haven’t already, subscribe to TresBohemes.com below to receive our newsletter directly in your inbox and never miss out.