Today we are revisiting the Golem of Prague. We’ve written about this before in our post The Legend of The Golem but our friend Barbara S. Weitz shared the following information which we’ve decided to share here with you because it’s so interesting. We hope you enjoy it.

Who is the Golem?

The Golem is an ancient Jewish Legend. Various versions exist.

The word golem originally meant lump and derived from the word glam meaning to wrap up. The term, golem, was used in the Bible (Psalms 139:16) to mean a developing or unfinished substance.

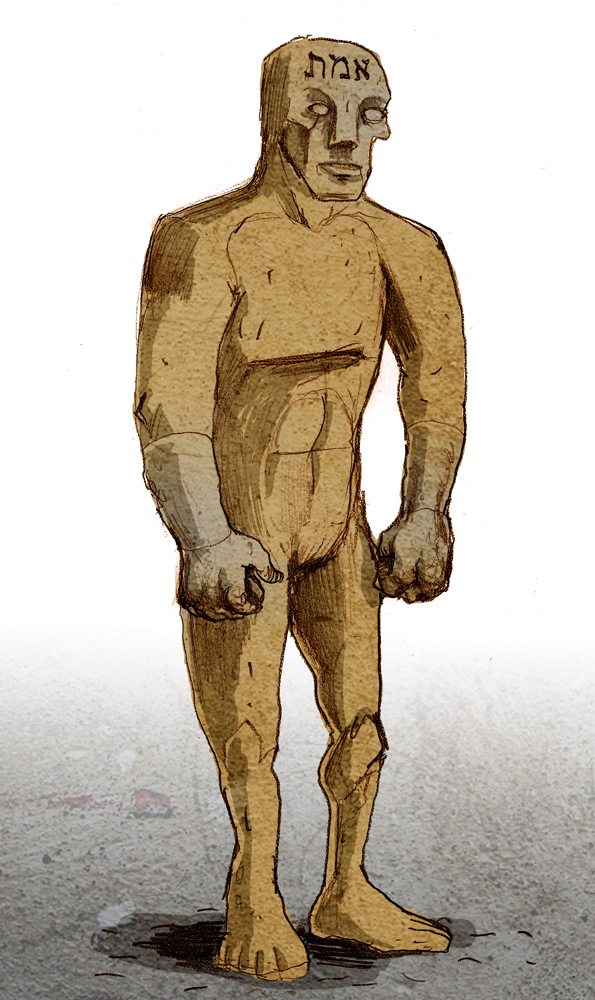

As a monster, golems were originally men made of inanimate material (such as clay or mud) endowed with life. The word “golems” gained its meaning as a monster during the Medieval period from legends of wizards who could bring effigies (figures) to life by using a charm or a written sacred word. The word was often written on paper and placed on the golem’s mouth or forehead. Removing the word would destroy the enchantment and life of the golem.

Anyone visiting Prague has an opportunity to encounter the Golem, the legendary being created and brought to life by Prague’s former Chief Rabbi Yehuda Low.

A Prague reproduction of the Golem

According to legend, the Golem has lain lifeless and undisturbed for centuries behind a small, triangular window in the attic of the synagogue in the Jewish Quarter. Many authors have written about the Golem, making it a popular figure in Jewish and European folklore.

Old New Synagogue of Prague with the rungs of the ladder to the attic on the wall. Legend has Golem lying in the loft.

The Chief Rabbi of Prague, Yehuda Low Ben Bezalel, lived from 1525 to 1609. During this period, the Jews were persecuted repeatedly by Christians, who spread terror through the ghetto. The attacks intensified during Passover when the Jews were often accused of using the blood of Christian children to bake matza, unleavened bread. This malicious slander inevitably stirred up Christian mobs to attack the ghetto, and the vastly outnumbered Jews were too weak to defend themselves.

It was a hopeless situation, until, as legend has it, Rabbi Low received a plan of deliverance in a dream. The instructions were simple: create a being to frighten the Jew-haters away.

Rabbi Low immediately went to work, summoning his wife Edam and his oldest student to help him make the Golem. The creature was to be composed of the four elements: earth, water, fire and air. They prepared themselves spiritually for this task for seven days. And on the 20th day of the Hebrew month of Adar in the Jewish year 5340, at the fourth hour after midnight, they went to the bank of the Moldau River and made the figure out of the clay soil. It was 10 feet tall and had basic human features.

The Rabbi told his wife to circle the prostrate figure seven times and say a certain mystical phrase. Suddenly the clay sculpture became red hot. Then, the Rabbi ordered his student to circle the figure seven times and say another mystical phrase. It cooled down and became damp, and suddenly, an unbelievable thing happened: fingernails started growing and hair covered his body. Now it was the rabbi’s turn to circle the creature seven times. The three of them then recited Genesis 2:7: ‘And God breathed into his nostrils the breath of life and man became a living soul.‘

Source: Etsy

The Golem opened his eyes immediately and stood up.

‘You must know that we have created you from clay and that you are here for one purpose only, and that is to save our people from evil,’ Rabbi Low told the Golem. ‘I name you Joseph. You must only listen to my orders and must do everything I ask you to do.’ The Golem nodded to show he understood. He was able to hear and see but could not talk.

The Golem, dressed in the clothes of the time, sat in a corner of Rabbi Low’s room all day long. He did not even help the Rabbi’s wife, a fact that irritated her. With everything she had to do, she could have used some extra help, but alas, he was not created for that purpose. He was only there to protect the Jews during times of danger. For this, he was able to go through fire and water or wade through dangerous floods.

Finally, the day of reckoning arrived. A small child was found dead in Prague and was thrown on the road to the ghetto. The Jews were accused of cold-blooded ritual murder, and soon, an angry mob carrying torches took to the streets looking for revenge. But the Golem rose to the occasion, pushing through the crowd and finding the very woman who killed the child. The terrified woman quickly confessed to the murder.

From then on, the Golem searched all carriages and wagons entering the Ghetto, to make sure that no dead child was hidden away. Residents of Prague were frightened because of the Golem’s eerie presence, and soon the blood accusations stopped. In fact, the Prague town council issued a decree which declared the accusations baseless and prohibited any repeat of them in the future.

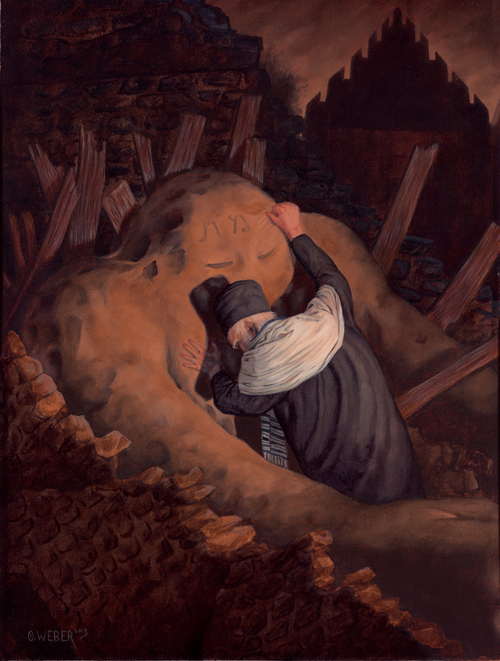

With this decree, Rabbi Low had achieved his goal, so he decided to take the breath of life away from the Golem. The rabbi did not want the Golem to fall into the hands of the wrong people, who might use the creature for evil. So the rabbi, his wife, and student took the Golem up to the small attic of the synagogue, circled around him again, and simultaneously uttered the mystical phrase that had brought the Golem to life but all in reverse order. Then, they wrapped the now lifeless Golem in a tallit (prayer shawl) and left him lying there to this day.

Golem is a Character in Dungeons and Dragons

The golem became part of Jewish folklore in the sixteenth century. The most famous golem in Jewish folklore was created by Rabbi Judah Loew of Prague to protect Jewish people from persecution. Loew’s golem was animated by a small tablet placed under its tongue and the word truth written on its forehead in Hebrew, “ameth.” To kill the golem the tablet had to be removed, and the first letter of “ameth” had to be erased to spell “meth,” meaning death.

The Hebrew letters on the creature’s head read “emét”, meaning “truth”. In some versions of the Chełm and Prague narratives, the Golem is killed by removing the first letter, making the word spell “mét”, meaning “dead”.

In Dungeons and Dragons, golems are giants (over 7-12 feet tall) made of various inanimate substances forming the shape of a person and are granted life by a series of spells cast by a magician or priest. The most common of these golems are made of flesh, clay, stone, or iron. Flesh golems are based on Frankenstein’s monster and must be made using parts from 6 or more bodies of dead people.

(Kytka’s note: A DnD Golem is a construct, a magically created monster in the Dungeons & Dragons role-playing game. They are based upon the golems of Jewish mythology. There are four standard types of golems; these are (from weakest to strongest): flesh golems, clay golems, stone golems, and iron golems.)

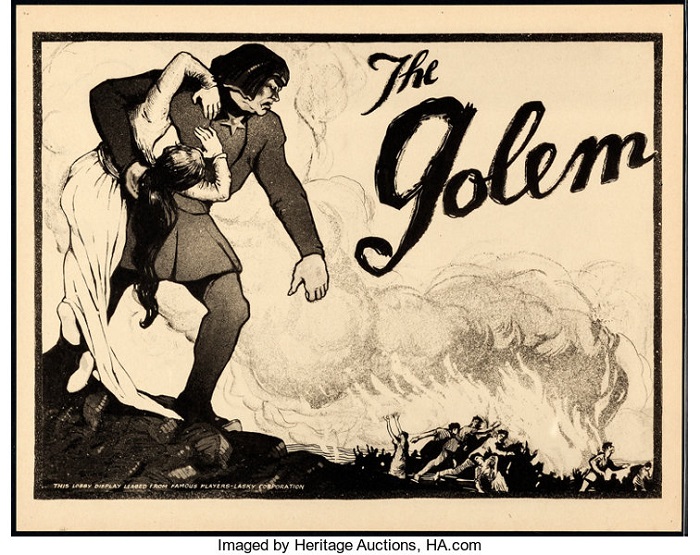

There is a 1920s silent film about the golem.

The Golem has also been made into an opera.

The Meyrink play of the Golem was performed in New York.

Spiritual and Mental Qualities of a Golem

The golem possesses no spiritual qualities, because, quite simply, it does not have a human soul. It has been given the ruah, the “breath of bones”, or “animal soul”, the basic life force in all living things, but possesses nothing higher. It is s typically not given a name. It is not considered a human being, nor does anyone in written accounts particularly concerned with its well-being or express any sadness at its deactivation. This isn’t cruelty so much as emotional indifference. The Golem is simply an animated thing, like a robot, with no real life or desires of its own. The act of creation is holy and more important than the creature itself.

As far as mental ability is concerned, the golem seems something like a well-trained dog, only without the emotional qualities. It understands what is said to it, follows directions, and often reports to only one master (typically its chief creator).

Physical Qualities of a Golem

As demonstrated by the techniques, there are a number of common “ingredients” in the golem recipe: virgin soil, freshwater, and often a Name that is inscribed upon or carried by the creature. There are also a number of common physical qualities attributed to the creature.

Interestingly enough, precise descriptions of these creatures are often vague. Though often depicted in art as large, murky, muddy creatures, or as “humanoid”, original literary sources would suggest they appeared to be human men (or in a rare case or two, a woman). The techniques described above often refer to creating a specific human body. Rabbi Zeira is not aware that the man sent to him is Rava’s creation until he tries to speak to it. Rabbi Loew and his assistants dress their golem in common clothes and present him as a servant; no one except a select few ever know what he really is.

Almost without exception, in original sources, the golem is mute, since the power of speech is connected with the soul, and only God can grant a man a soul. Occasionally I’ve come across exceptions in variants of the story, often in children’s books, in which the creature says a few words or argues not to be deactivated¬this seems to be more of a plot device than anything else. Moshe Idel relates a talk of Ben Sira and his father Jeremiah, who create a golem that promptly asks to be destroyed and tells them how to do it, lest people believe the two mortal men are gods themselves. This is another plot device used to tell a moral and cautionary tale.

The more elaborate stories of Rabbi Loew’s golem (which he calls Yosele) describe the creature as a very physical, almost animal one. He is a large man, possessed of great strength, with acute hearing and a lack of fear. He cannot speak, but comprehends basic instructions, in some cases too literally. He sleeps and can be injured.

In most golem stories (of Loew or others), the creature, empowered by the Name of God on its person, continues to grow larger and stronger from day to day, until it is either no longer practical or too dangerous to keep active. In some stories, it eventually runs amok. In these cases, the ultimate moral is fairly clear: only God should partake in the creation of this sort.

Some medieval rabbis actually debated the hypothetical social situations which might arise if dealing with a golem were a necessity: is it considered murder when you deactivate it? Does it count as a person when you need a minyan (ten people) required to have synagogue services or for other procedures? Should its corpse be handled as a Jewish corpse, and does nonstandard handling of its corpse cause impurity? The general consensus was that the golem is a sort of non-human entity, because it does not possess a soul, nor was it born.

The Classic Narrative

The most famous golem narrative involves Rabbi Judah Loew the Maharal of Prague, a 16th-century rabbi. He is reported to have created a golem to defend the Prague ghetto of Josefov from Anti-Semitic attacks. The story of the Golem first appeared in print in 1847 in a collection of Jewish tales entitled Galerie der Sippurim, published by Wolf Pascheles of Prague. About sixty years later, a fictional account was published by Yudl Rosenberg (1909). According to the legend, Golem could be made of clay from the banks of the Vltava river in Prague.

[Art by Owen William Weber, website.]

Following the prescribed rituals, the Rabbi built the Golem and made him come to life by reciting special incantations in Hebrew. As Rabbi Loew’s Golem grew bigger, he also became more violent and started killing people and spreading fear. Rabbi Loew was promised that the violence against the Jews would stop if the Golem was destroyed. The Rabbi agreed. To destroy the Golem, he rubbed out the first letter of the word “emet” from the golem’s forehead to make the Hebrew word “met”, meaning death. The existence of a golem is sometimes a mixed blessing. Golems are not intelligent – if commanded to perform a task, they will take the instructions perfectly literally.

The Golem as Protector

In Jewish legend, an image or form that is given life through a magical formula. A golem frequently took the form of a robot or automaton. In the Hebrew Bible (see Psalms 139:16) and in the Talmud, the term refers to an unformed substance. Its present meaning developed during the Middle Ages, when legends arose of wise men who could instill life in effigies by the use of a charm. The creatures were sometimes believed to offer special protection to Jews. The best-known of the golem stories concerned a Rabbi Löw of 16th-century Prague, who was said to have created a

the golem that he used as his servant.

[The Rabbi and the Golem by Lindsey Leigh, Freelance Illustrator.]

Literary Aspects of the Legend of the Golem

The Legends concerning the golem, especially in their later forms, served as a favorite literary subject, at first in German literature-of both Jews and non-Jews-in the 19th century, and afterward in modern Hebrew and Yiddish literature. To the domain of belles lettres also belongs the book Nifla’ot Maharal im ha-Golem (“The Miraculous Deeds of Rabbi Loew with the Golem”; 1909), which was written after the blood libels of the 1890s. The connection between the golem and the struggle against ritual murder accusations is entirely a modern literary invention.

Interest in the golem legend among writers, artists, and musicians became evident in the early 20th century. The golem was also invariably the benevolent robot of the later Prague tradition and captured the imagination of writers active in Austria Czechoslovakia, and Germany. The outstanding work about the golem was the novel entitled Der Golem (1915; Eng. 1928) by the Austrian writer Gustav Meyrink (1868-1932), who spent many years in Prague. Meyrink’s book, notable for its detailed description and nightmare atmosphere, was a terrifying allegory about man’s reduction to an automaton by the pressures of modern society.

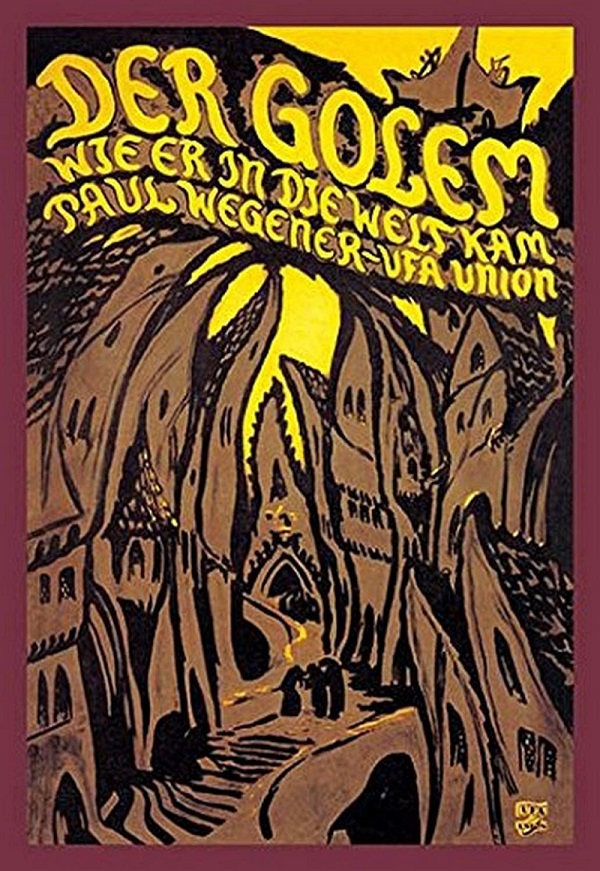

The Golem, German film from 1920.

The Golem – How He Came into the World (Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam) is a film of great power, as hypnotic as a German Expressionist vision of life as a waking dream. The dim light and looming shadow were photographed by Karl Freund (born on January 16, 1890, in the Bohemian city of Koeniginhof, then part of the Austria-Hungarian Empire; now known as Dvur Kralove in the Czech Republic; who also shot two German Expressionist masterpieces: Fritz Lang’s Metropolis and F.W. Murnau’s The Last Laugh. Freund later emigrated to America.

(Kytka’s note: The Golem was released in German cinemas on October 29, 1920, heralding, with its fantastic themes, excessive acting, and distorted scenographies designed by Hans Poelzig, the advent of Expressionism which began with the film The Cabinet of Doctor Caligari (1920 ) by Robert Wiene.)

Hans Poelzig’s stylized sets convey the claustrophobia of ghetto life, with curved stone walls and sharply pointed roofs. The two sets of circular stairs the characters climb down to enter the rabbi’s study look like the twin chambers of a human heart.

However, The Golem is not really a German Expressionist story; it is more a combination of Jewish mysticism and fairy tale. Director Wegener portrays the supernatural elements of the story without irony or psychological explanation as if we were truly in medieval Prague when people would have believed that an amulet and an incantation could bring a clay figure to life.

In the following years since The Golem‘s release and rediscovery, it has been considered an early classic in horror cinema, and one of the first films to introduce the concept of the “man-made monster”. The film is listed in 101 Horror Movies You Must See Before You Die, a spin-off of 1001 Films You Must See Before You Die, which the authors called “a classic of German expressionist cinema” It was presented at the Star and Shadow cinema in 2014 as part of the British Film Institute’s Gothic season.

The 1920 film set in the Jewish ghetto of Prague laid the groundwork for one of the most iconic horror films of all time.

The film is an early example of the man-made monster genre and was a predecessor to the wildly influential Frankenstein film that came out a decade later, directed by James Whale and starring Boris Karloff.

There is much in there that was used for future horror movies for ages.

This idea of bringing something to life, of creating something you think is going to save you and then works against you… It’s a theme that runs through many horror movies, beginning with The Golem.

You can watch the 1920 film, The Golem, in its entirety below…

Golems are frequently depicted in movies and television shows. Programs with them include the following:

- The Golem (German: Der Golem, shown in the United States as The Monster of Fate), a 1915 German silent horror film, written and directed by Paul Wegener and Henrik Galeen.

- The Golem and the Dancing Girl (German: Der Golem und die Tänzerin), a 1917 German silent comedy-horror film, directed by Paul Wegener and Rochus Gliese.

- The Golem: How He Came into the World (German: Der Golem, wie er in die Welt kam, also referred to as Der Golem), a 1920 German silent horror film, directed by Paul Wegener and Carl Boese.

- Le Golem (Czech: Golem), a 1936 Czechoslovakian monster movie directed by Julien Duvivier in French.

- The Emperor and the Golem (Czech: Císařův pekař a pekařův císař) is a two-part Czechoslovak historical fantasy comedy film produced in 1951.

- Daimajin (Japanese: 大魔神) is a Japanese film released in 1966.

- It! (alternate titles: Anger of the Golem and Curse of the Golem) is a 1967 British horror film made by Seven Arts Productions and Gold Star Productions, Ltd.

- Miss Golem (Czech; Slečna Golem), 1973. Directed by Jaroslav Balík.

- Golem, the Spirit of the Exile (French: Golem, l’esprit de l’exil) is a 1992 drama film directed by Amos Gitai.

- Golem is a short Animation By Alon Boroda and Ron Nadel from 2006. Watch on YouTube.

- The Golem is a 2018 Israeli period supernatural horror film directed by Doron and Yoav Paz, and written by Ariel Cohen.

Further Studies

- The Golem by Gustav Meyrink (Dover, 1976 (1928)

- The Golem by H. Leivick (in The Dybbuk and Other Great Yiddish Plays), Bantam, 1966

- The Golem of Prague by Gershon Winkler (Judaica Press, 1980)

- The Sword of the Golem by Abraham Rothberg (Bantam, 1970)

- The Prague Golem: Jewish Stories of the Ghetto by Chajim Bloch (January 1, 2002)

- The Red Magician by Lisa Goldstein (Pocket, 1983)

- The Golem in Literature, Film, and Stage, article by Mark R. Leeper Copyright 1985, 1992, 1994, 1996, 2002 by Mark R. Leeper

- Golem, a play by Moni Ovadia

- Le Golem or The Man of Stone (1936) by Julien Duvivier

- Snow in August by Pete Hammill, June 11, 2013

- Snow in August, television movie, 2001

- The Golem and the Jinni by Helene Wecker, Harper Publishing

- The Golem at International Movie database.

(Note: Film and book list is from both Kytka and Barbara.)

Guest Post Author

Prof. Barbara S. Weitz taught at FIU for 30 years and was the Director of the FIU Study Abroad Program to the Czech Republic for 22 years. Included in the program was a 2-week Czech Cinema course which included participation in the prestigious Karlovy Vary Film Festival held every summer.

Prof. Barbara S. Weitz taught at FIU for 30 years and was the Director of the FIU Study Abroad Program to the Czech Republic for 22 years. Included in the program was a 2-week Czech Cinema course which included participation in the prestigious Karlovy Vary Film Festival held every summer.

Retired, Florida International University

Director of Film Studies

Director of Czech Studies Program

Director of JCC Israeli Film Series

Read her entire profile here.

Connect with Barbara on LinkedIn or at 10 Stars.

Thank you in advance for your support…

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks, and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

We appreciate you more than you know!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

I have seen this character and never knew the background. Now I know. Thanks.

I find it interesting to think of the Golem as the first Frankenstein, something I never considered before. Thank you for another excellent article.

Fabulous essay!