Věrni zůstaneme is the motto of the Czech Republic Army. It means “We Shall Remain Faithful”, “We Will Remain Faithful”, or “We Remain Faithful”.

After the Nazi seizure of power in 1933, Germany demanded the “return” of the ethnic German population of Czechoslovakia—and the land on which it lived—to the German Reich. In the late summer of 1938, Hitler threatened to unleash a European war unless the Sudetenland was ceded to Germany. The Sudetenland was a border area of Czechoslovakia containing a majority ethnic German population as well as all of the Czechoslovak Army’s defensive positions in event of a war with Germany.

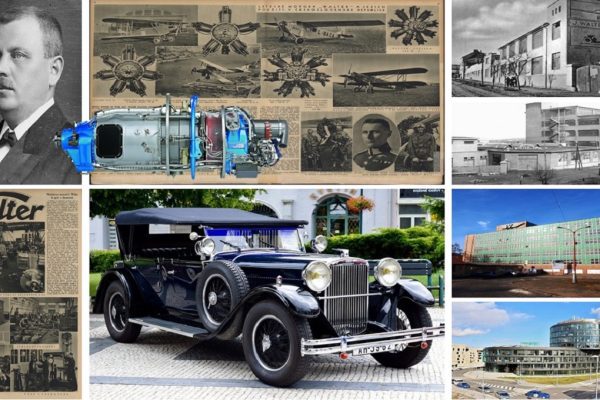

Czech flyer, responding to the Munich Agreement

The leaders of Britain, France, Italy, and Germany held a conference in Munich on September 29–30, 1938. In what became known as the Munich Agreement (or Pact), they agreed to the German annexation of the Sudetenland in exchange for a pledge of peace from Hitler.

1938 was the fateful year, the period of the Munich betrayal and the greatest humiliation of the Czechoslovak Republic. To this day, there are passionate debates among military analysts, historians, and the general public as to whether Czechs should have refused the cession of the Sudetenland and defended the Czech homeland with arms in hand.

For many years, I have often wondered how things would have turned out if the Czechs had responded to the Munich Dictator in 1938 with a fight.

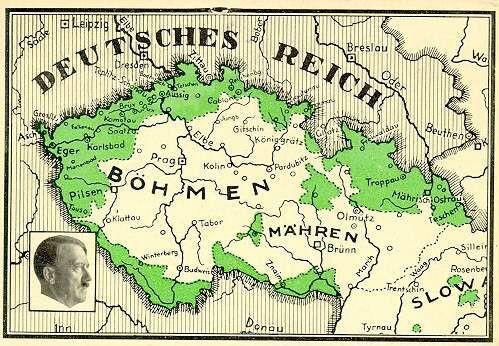

The Munich Agreement

Munich Agreement, (September 30, 1938), a settlement reached by Germany, Great Britain, France, and Italy that permitted German annexation of the Sudetenland, in western Czechoslovakia.

(The Sudetenland encompassed areas well beyond those mountains, however. Parts of the now Czech regions of Karlovy Vary, Liberec, Olomouc, Moravia-Silesia, and Ústí nad Labem are within the area called Sudetenland.)

After his success in absorbing Austria into Germany proper in March 1938, Adolf Hitler looked covetously at Czechoslovakia, where about three million people in the Sudetenland were of German origin. Hitler wanted to unite all Germans into one nation. In September 1938 he turned his attention to the three million Germans living in the part of Czechoslovakia called the Sudetenland.

The Sudetenland was inhabited by over 3 million ethnic Germans, comprising about 23 percent of the population of Czechoslovakia. Hitler said he wanted his people – but his interest in Czechoslovakia was largely economic. Germany had the second-largest economy in the world but had more people than German agriculture was capable of feeding. It was also lacking many raw materials, which had to be imported.

The Sudetenland was inhabited by over 3 million ethnic Germans, comprising about 23 percent of the population of Czechoslovakia. Hitler said he wanted his people – but his interest in Czechoslovakia was largely economic. Germany had the second-largest economy in the world but had more people than German agriculture was capable of feeding. It was also lacking many raw materials, which had to be imported.

The Sudentenland possessed huge chemical works and lignite mines, as well as textile, china, glass factories, and farmlands. It was also home to the Czechoslovak Army’s defensive positions in event of a war with Germany. You can see on the map, the area Hitler wanted was the green area. It included major Czech cities such as Aš, Ústí nad Labem, Podmokly, Most, Cheb, Sokolov, Jablonec nad Nisou, Kraslice, Krnov, Karlovy Vary, Chomutov, Litoměřice, Šumperk, Nový Jičín, Liberec, Žatec, Krásná Lípa, Šternberk, Teplice, Děčín, Opava, Varnsdorf, among others.

You can see all of the cities within the Sudetenland region here.

In April he discussed with Wilhelm Keitel, the head of the German Armed Forces High Command, the political and military aspects of “Case Green,” the code name for the envisaged takeover of the Sudetenland. A surprise onslaught “out of a clear sky without any cause or possibility of justification” was rejected because the result would have been “a hostile world opinion which could lead to a critical situation.”

Hitler told the Sudeten German Party to begin a program of unrest and to make their demands for a plebiscite known to the Czech Government. In April of 1938, this led to the party announcing a plan for Sudeten self-government and the civil unrest grew in intensity. The Sudeten claimed that they were being persecuted and German newsreels backed up this assertion.

In May of 1938, Hitler ordered German troops into positions along the border with Sudetenland. This was to intimidate the Czech government into giving in to the demands of the Sudeten Germans and to provide support for them should the alleged persecutions continue. In response, the Czech army was mobilized and stationed in defensive positions along the border.

Throughout the summer there was a tense stand off between the German and Czech governments. Hitler assured the International Community that all he wanted was for the ethnic Germans to get what they wanted and join Germany. Further rioting took place throughout the Sudetenland and martial law was imposed by the Czech government. It now looked as though Hitler was about to invade.

Decisive action would take place only after a period of political agitation by the Germans inside Czechoslovakia accompanied by diplomatic squabbling which, as it grew more serious, would either build up an excuse for war or produce the occasion for a lightning offensive after some “incident” of German creation. Moreover, disruptive political activities inside Czechoslovakia had been underway since as early as October 1933, when Konrad Henlein founded the Sudetendeutsche Heimatfront (Sudeten-German Home Front).

By May 1938 it was known that Hitler and his generals were drawing up a plan for the occupation of Czechoslovakia. The Czechoslovaks were relying on military assistance from France, with which they had an alliance. The Soviet Union also had a treaty with Czechoslovakia, and it indicated a willingness to cooperate with France and Great Britain if they decided to come to Czechoslovakia’s defense, but the Soviet Union and its potential services were ignored throughout the crisis.

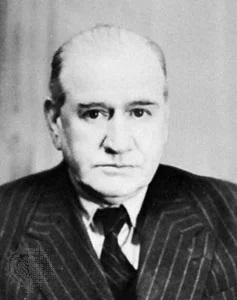

Édouard Daladier.

As Hitler continued to make inflammatory speeches demanding that Germans in Czechoslovakia be reunited with their homeland, war seemed imminent. Neither France nor Britain felt prepared to defend Czechoslovakia, however, and both were anxious to avoid a military confrontation with Germany at almost any cost.

In France, the Popular Front government had come to an end, and on April 8, 1938, Édouard Daladier formed a new cabinet without Socialist participation or Communist support. Four days later Le Temps, whose foreign policy was controlled by the Foreign Ministry, published an article by Joseph Barthelemy, a professor at the Paris Law Faculty, in which he scrutinized the Franco-Czechoslovak treaty of alliance of 1924 and concluded that France was not under obligation to go to war in order to save Czechoslovakia.

Earlier, on March 22, The Times of London had stated in a leading article by its editor, G.G. Dawson, that Great Britain could not undertake war to preserve Czech sovereignty over the Sudeten Germans without first clearly ascertaining the latter’s wishes; otherwise Great Britain “might well be fighting against the principle of self-determination.”

Sudeten Germans marching in Karlsbad, Germany, April 1937.

On April 28–29, 1938, Daladier met with British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain in London to discuss the situation. Chamberlain, unable to see how Hitler could be prevented from destroying Czechoslovakia altogether if such were his intention (which Chamberlain doubted), argued that Prague should be urged to make territorial concessions to Germany. Both the French and British leadership believed that peace could be saved only by the transfer of the Sudeten German areas from Czechoslovakia.

Neville Chamberlain.

In mid-September Chamberlain offered to go to Hitler’s retreat at Berchtesgaden to discuss the situation personally with the Führer. Hitler agreed to take no military action without further discussion, and Chamberlain agreed to try to persuade his cabinet and the French to accept the results of a plebiscite in the Sudetenland.

Daladier and his foreign minister, Georges-Étienne Bonnet, then went to London, where a joint proposal was prepared to stipulate that all areas with a population that was more than 50 percent Sudeten German be turned over to Germany. The Czechoslovaks were not consulted. The Czechoslovak government initially rejected the proposal but was forced to accept it on September 21.

On September 22 Chamberlain again flew to Germany and met Hitler at Bad Godesberg, where he was dismayed to learn that Hitler had stiffened his demands: he now wanted the Sudetenland occupied by the German army and the Czechoslovaks evacuated from the area by September 28. Chamberlain agreed to submit the new proposal to the Czechoslovaks, who rejected it, as did the British cabinet and the French. On the 24th the French ordered a partial mobilization; the Czechoslovaks had ordered a general mobilization one day earlier. Having at that time one of the world’s best-equipped armies, Czechoslovakia could mobilize 47 divisions, of which 37 were for the German frontier, and the mostly mountainous line of that frontier was strongly fortified.

The Dreesen Hotel in Bad Godesberg, Germany, where Neville Chamberlain and Adolf Hitler met on September 22, 1938.

On the German side the final version of “Case Green,” as approved by Hitler on May 30, showed 39 divisions for operations against Czechoslovakia.

The Czechoslovaks were ready to fight but could not win alone.

In a last-minute effort to avoid war, Chamberlain proposed that a four-power conference be convened immediately to settle the dispute. Hitler agreed, and on September 29 Hitler, Chamberlain, Daladier, and Italian dictator Benito Mussolini met in Munich. The meeting in Munich started shortly before 1 PM. Hitler could not conceal his anger that, instead of entering the Sudetenland as a liberator at the head of his army on the day fixed by himself, he had to abide by the three Powers’ arbitration, and none of his interlocutors dared insist that the two Czech diplomats waiting in a Munich hotel should be admitted to the conference room or consulted on the agenda.

(From left) Italian leader Benito Mussolini, German Chancellor Adolf Hitler, a German interpreter, and British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain meeting in Munich, on September 29, 1938.

Nevertheless, Mussolini introduced a written plan that was accepted by all as the Munich Agreement. (Many years later it was discovered that the so-called Italian plan had been prepared in the German Foreign Office.) It was almost identical to the Godesberg proposal: the German army was to complete the occupation of the Sudetenland by October 10, and an international commission would decide the future of other disputed areas.

German Chancellor Adolf Hitler (left) and British Prime Minister Neville Chamberlain (third from left) in Munich, Germany, shortly before the signing of the Munich Agreement, 1938.

Czechoslovakia was informed by Britain and France that it could either resist Germany alone or submit to the prescribed annexations. The Czechoslovak government chose to submit.

Before leaving Munich, Chamberlain and Hitler signed a paper declaring their mutual desire to resolve differences through consultation to assure peace. Both Daladier and Chamberlain returned home to jubilant welcoming crowds relieved that the threat of war had passed, and Chamberlain told the British public that he had achieved “peace with honor. I believe it is peace for our time.” His words were immediately challenged by his greatest critic, Winston Churchill, who declared, “You were given the choice between war and dishonor. You chose dishonor and you will have war.”

Indeed, Chamberlain’s policies were discredited the following year, when Hitler annexed the remainder of Czechoslovakia in March and then precipitated World War II by invading Poland in September. The Munich Agreement became a byword for the futility of appeasing expansionist totalitarian states, although it did buy time for the Allies to increase their military preparedness.

The Czechoslovaks were dismayed by the Munich settlement. They were not invited to the conference and felt they had been betrayed by the British and French governments. The agreement averted the outbreak of war but gave Czechoslovakia away to German conquest.

The Munich Agreement had the opportunity to stop the war but failed due to its weak predecessors and the strong pattern of appeasement towards Hitler that had already been established.

Meanwhile, the 1938 Munich Agreement resulted in S.S. mastermind Reinhard Heydrich becoming the de facto ruler of Prague – which is another horror story in itself.

From my friends at Czech Movie:

The famous final words of Edvard Benes’s funeral speech, delivered over Masaryk’s coffin on 21 September 1937, became a symbol of the democratic anti-fascist Czechoslovak resistance, and symbolically also the title of the film, which was to be a kind of message from the exiled government in London to the Czechoslovak public.

Step by step, this comprehensive account traces the uneasy journey of the Czechoslovak anti-fascists, beginning with the bitter Munich prologue of autumn 1938 and the even sadder 15 March 1939. It goes on to recount the difficult years of the ‘golden era’ of the German blitzkrieg, during which the Wehrmacht occupied most of Europe. It does not shy away from the critical moments of domestic and foreign resistance, and it does not gloss over any of the more important moments of the Second World War, whether on the Eastern, Western, or North African front.

The triumph of the predominantly democratic coalition of the victorious United Nations is symbolized by the film’s climax, which is a summarizing and generalizing speech by President Edvard Benes, reporting both on the activities of the foreign resistance in London and Moscow and on the first steps in the liberated homeland that the domestic governments of Czechs and Slovaks should and could have taken during the first weeks and months of the Third Czechoslovak Republic’s brief existence. Needless to say, these were intentions and intentions which differed considerably from what actually began to happen in our country from May 1945.

A completely unknown and rarely screened documentary by the outstanding Czech director Jiri Weiss.

I’m very glad that this film has gained attention and has been transferred to DVD.

I’m very glad that this film has gained attention and has been transferred to DVD.

The bonus features from the Front and the returns and convalescent homes are also a great addition to this film.

I hope that this work will soon become more widely known.

You can order this film in Czech with English subtitles from the Czech Movie website.

I have purchased many films from them over the years and have always had excellent service – highly recommended!

Or, if you speak Czech, you can watch it on YouTube below.

Note that the DVD is of excellent quality, offers bonus features, and has English subtitles.

It is a must for anyone interested in this part of Czech history.

Sources:

- Britannica, The Editors of Encyclopaedia. “Munich Agreement”. Encyclopedia Britannica, 23 Sep. 2022.

- United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. “Czechoslovakia”. Holocaust Encyclopaedia, 23 Sep. 2022.

- History Net. “How the Munich Agreement Unleashed the Butcher of Prague”, 23 Sep. 2022.

I’d love to read your comments!

We tirelessly gather and curate valuable information that could take you hours, days, or even months to find elsewhere. Our mission is to simplify your access to the best of our heritage. If you appreciate our efforts, please consider making a donation to support the operational costs of this site.

You can also send cash, checks, money orders, or support by buying Kytka’s books.

Your contribution sustains us and allows us to continue sharing our rich cultural heritage.

Remember, your donations are our lifeline.

If you haven’t already, subscribe to TresBohemes.com below to receive our newsletter directly in your inbox and never miss out.