This is the story of Zika and Lída Ascher, famous Czech textile innovators who were entrepreneurs, artists and the United Kingdom’s hottest designer couple. They left Czechoslovakia before the break of World War II and built a textile business empire in the United Kingdom. The tale of Zika and Lida Ascher is one of survival, resolve, and creative innovation.

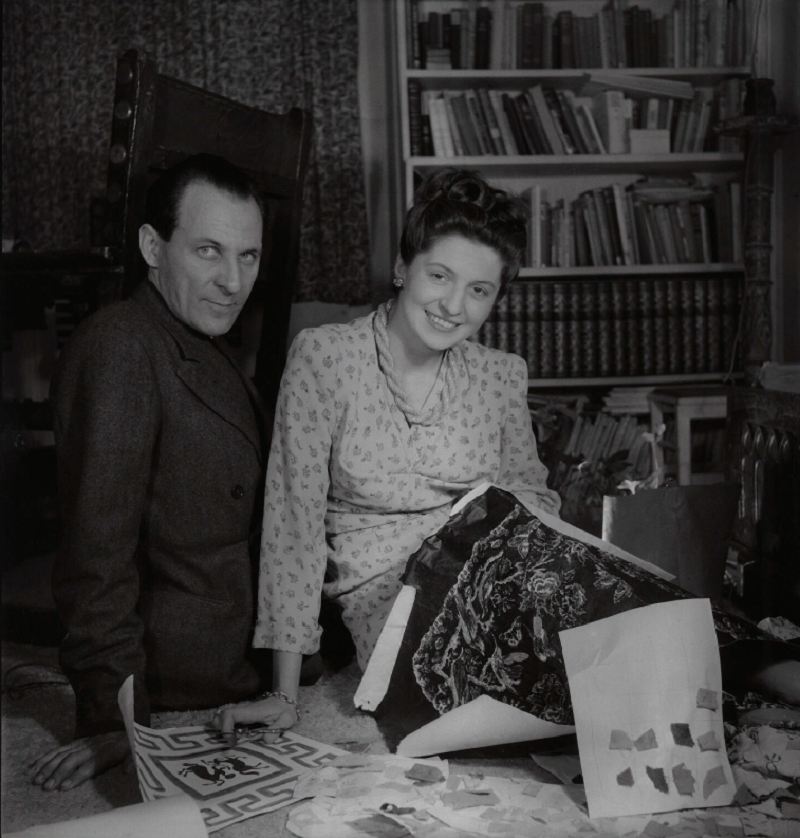

Zika Ascher; Lida Ascher by Francis Goodman Zika Ascher; Lida Ascher © National Portrait Gallery, London

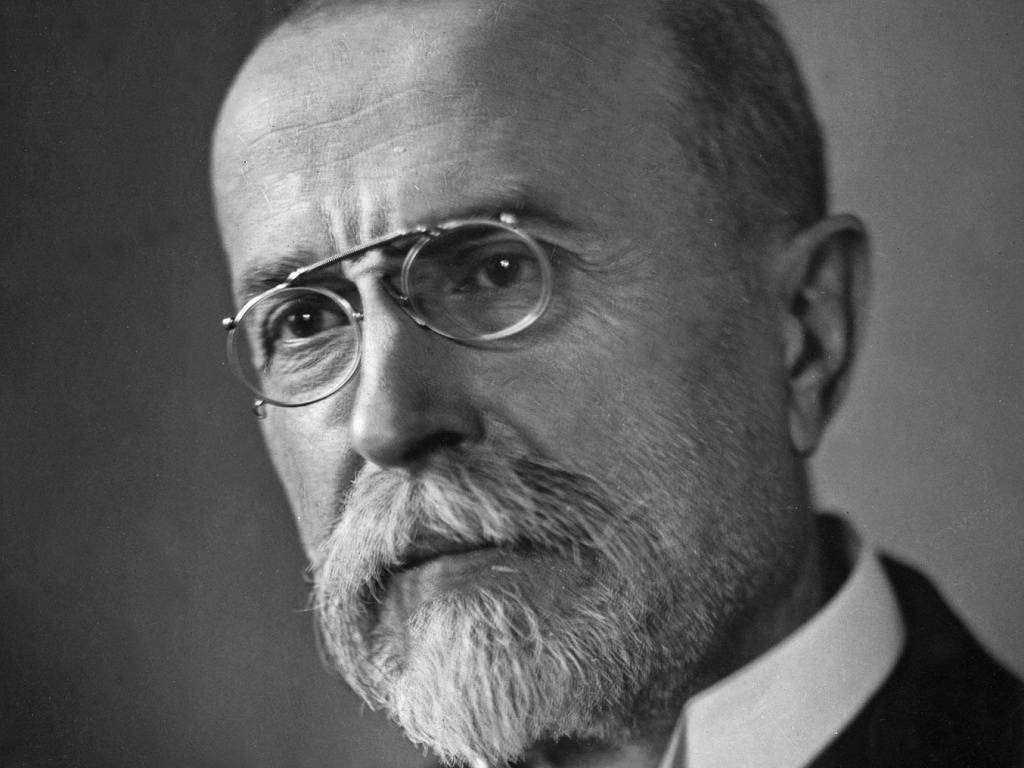

Zika Ascher (April 3, 1910 – September 5, 1992), born Zikmund Ascher was born to a wealthy Jewish family of textile manufacturers in Prague. A world champion skier in his youth, he was known as ‘the mad silkman’, a reference to his bravado and recklessness on the ski slopes and his family’s fabric business. He competed in three world championships, in ’35, ’37 and ’38. He was also picked for the ’36 Winter Olympics in Germany, in Garmisch, but unfortunately hurt himself in the practice race, so he didn’t actually compete.

On day in 1938 Lida Tydlitatova walked into his shop. A beautiful Catholic girl whose father built a magnificent villa on Slunná street in Prague, she immediately caught his attention. Lida was also an accomplished sportswoman, she was a keen skier and swimmer. She was educated, and had attended finishing school in Switzerland and university in Grenoble, France. She was a very proper, pre-war, Westernized Czech lady.

Zika (on the left) and Lida Ascher with an unknown man in Na Příkopě Street in Prague, 1938, Ascher Family Archive

She came into the store because she was frustrated at the lack of decent skiing clothes for women, so much so that she decided to make her own outfit, and went into Zika’s store to buy the fabric.

Zika and Lida immediately had a great rapport and attraction, but Lida’s mother was fiercely anti-Semitic. Despite family opposition, it became clear that Zika and Lida were going to marry. On December 22, 1938, just a few short weeks after Kristallnacht, Zika Ascher was baptized and converted to Catholicism; and two months later the couple married and left immediately on their honeymoon.

For the rest of their lives, the Aschers swore that they had only left Czechoslovakia for a honeymoon trip, but they went first to Norway, only to discover that Hitler had annexed the Sudetenland and they could not return home. In a fortuitous twist of fate, the pair landed at Newcastle with 18 trunks of belongings. They were helped to enter the UK by the Ski Club of Great Britain. By March 20, 1939, they were living in London. It could be said that their passion for skiing saved their lives.

Zika’s family remained in Prague. They secured a certificate to say that they were not Jewish, but Aryan, enabling them to survive although the shop and all Zika’s remaining assets were confiscated, first by the Nazis and then after the war by the Communist regime.

Arriving in London in 1939, Zika and Lida had few contacts or prospects for business. After a short stint in the army he was medically discharged and returned to London determined to set up a textile firm. It was Lida who first began designing fabrics with floral and calligraphy patterns.

Unable to get his business started until late 1941 due to the Battle of Britain, Zika quickly incorporated his firm and set up a silk-screen print works in London. Zika and Lida had no formal training in design, but an innate sense of color, proportion and pattern.

Their lack of formal training would prove an asset to the young couple as their loose impulsive designs stood out among their more formal competitors.

Zika was a Czech textile businessman, artist and designer who became pre-eminent in the related fields of British textiles, art, and fashion. He created his own textile company with Lida, which made its name with experimental fabrics and scarves designed by famous contemporary artists. Zika had an encyclopedic knowledge of textiles, dyes and chemicals, and Lida had exquisite taste and a willingness to approach artists and designers.

Zika and Lída Ascher, photo: Archives of the Ascher family

Zika had grown up with a keen interest in art, a passion which only grew through visits with his elder cousin Ernst Ascher, who was an African art dealer in Paris and a close friend to André Derain, Georges Braque, and Pablo Picasso.

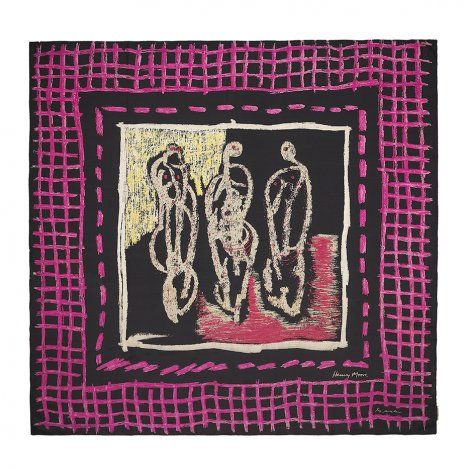

During the war, Zika would often wander the National Gallery looking at the works of contemporary artists such as Henry Moore, Graham Sutherland, and Ben Nicholson. Intrigued by the potential intersection of fine art and industry, and emboldened by the initial success of his firm, Ascher sought out Moore to propose a collaboration.

Ascher felt that textiles were a medium that was accessible to the wider public, and would allow contemporary artists to communicate their modernist ideals about design to a larger audience.

Moore was enthused with the concept and in late 1943 began work on four notebooks specifically for this purpose. Ascher and Moore began translating the artist’s drawings into textiles in 1944.

The printing process was a collaboration between the two men and the first design took six months of patient trials. The spirit or handwriting of the work was more important than an exact reproduction of every small mark and uneven line. Moore used wax crayon and watercolor wash for his sketches, so Ascher had the negatives for the screens made using the same wax resistant technique.

It was during this time of collaboration with Moore that Zika saw the potential of screen-printing as an artistic medium. Screen-printing allowed an artist to produce a work on a large scale that could be editioned and still retain all the original intent and characteristics of the artist’s hand.

Of course, he shared all of this with Lida.

Together, the young couple successfully redefined the bleak face of post-war British textiles throughout the 1940s with electrifying bursts of color and life, which came to symbolize a new era of optimism and hope. They were brave enough to experiment with unconventional fabrics including silk, wool, rayon, parachute nylon, mohair and cheesecloth, producing sumptuous designs that forever altered the fashion landscape.

Watch this one-minute film:

In Britain, he became known as “the Prince of Prints” because the Ascher’s, uniquely among other refugees, developed an extraordinary fashion fabric business whose calling card was the “Ascher Square”, a silk scarf with a design from the great artists of the day.

What was then known as The Ascher Project, to create innovative textiles based on contemporary art, ran in tandem with the Ministry of Information’s propaganda initiative, to introduce modern art to the “man on the street”. The War Pictures at the National Gallery in 1944 included paintings by Henry Moore, and there is footage of Zika Ascher trawling the National Gallery rooms, inspecting Moore’s work. It was not long before Ascher had Moore designing scarves, curtain fabrics and dress fabrics, creating a vibrant new design language that was to be accessible to all.

With Moore as the first participating artist, Zika then launched an initiative referred to as the Ascher Squares. The squares were produced in small, hand-numbered limited editions of 150-600; the screens from which they were printed were destroyed after the series had been made. These works could then be used as scarves or wall hangings.

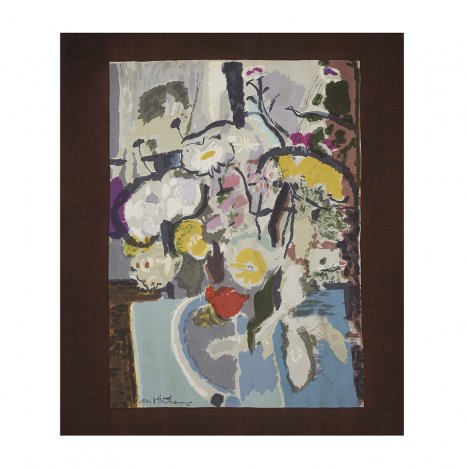

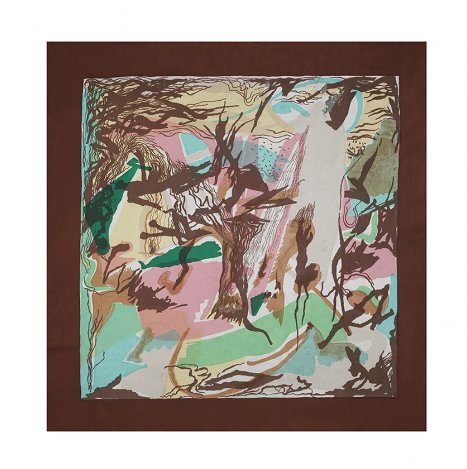

The Ascher’s then began approaching top artists, including Matisse, André Derain, Graham Sutherland, Ivon Hitchens, Hodgkins, Marie Laurencin, Jean Cocteau, Antoni Clavé, and others, to produce designs for a special collection of scarves known as the Ascher Squares.

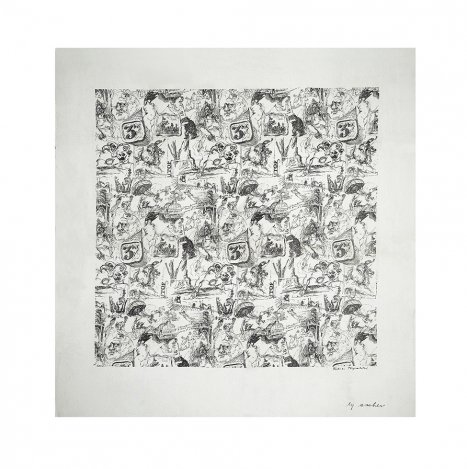

The pair made a series of pioneering innovations, collaborating with the world’s leading artists on a series of iconic silk scarves known as the Ascher Squares. The project quickly grew through word of mouth among the British artistic community. Barbara Hepworth, Ben Nicholson, and Graham Sutherland created works, while younger artists such as Lucian Freud and Robert Macbryde also collaborated with Ascher. Having had great success with British artists, Ascher set his sights on the vibrant artistic community in France. Enthusiasm for Ascher’s project was not shared by all, and Henri Matisse’s agent said that he would not even present the artist with the idea.

The artists of the Ascher Squares project represent a cross-section of the post war European art community. They were old and young, eminent and emerging, sculptors, painters, and theater designers. They came from England, France, Greece, Spain, America, and Russia. What they shared was a unique inspiration to do something new and different, and bring life back to a war-torn Europe.

Fueled by his passion and belief in the project, he determined that his success was dependent on speaking with the artists directly. Picking up the phone he called Matisse, Derain, Picasso, and Braque. Productive relationships with both Matisse and Derain followed and once again the project blossomed.

Soon Ascher found himself working with Marie Laurencin, Alexander Calder, Jean Cocteau, Nicolas De Stäel, Oscar Dominguez, and Antoni Clavé among others.

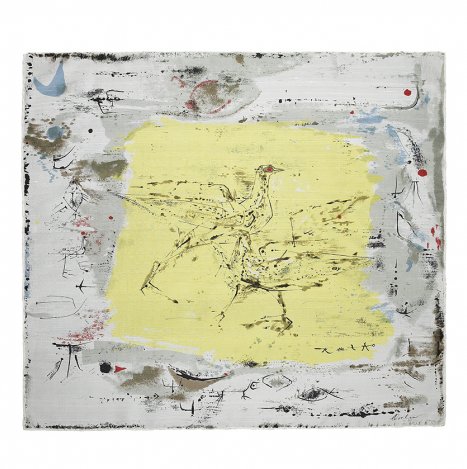

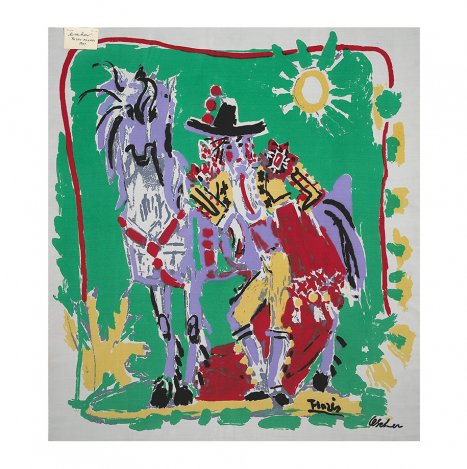

Let’s look at some of the famous and beautiful Ascher Squares from the Ascher Squares website.

Zao Wou-Ki

Robert Colquhoun

Philip Jullian

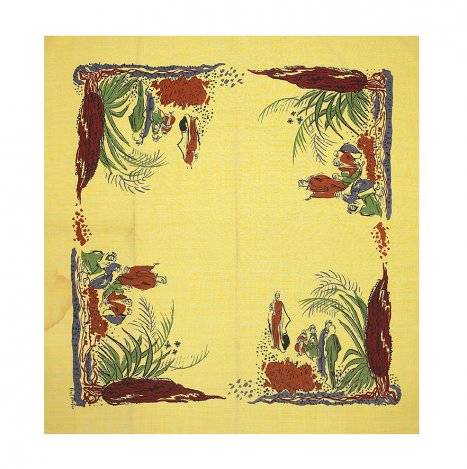

Pedro Flores

Pablo Picasso

Oscar Dominguez

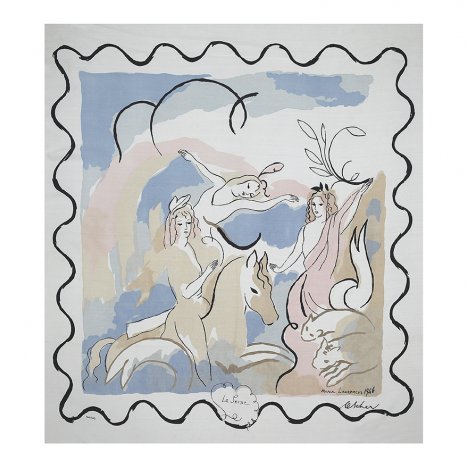

Marie Laurencin

Keith Vaughan

Julian Trevelyan

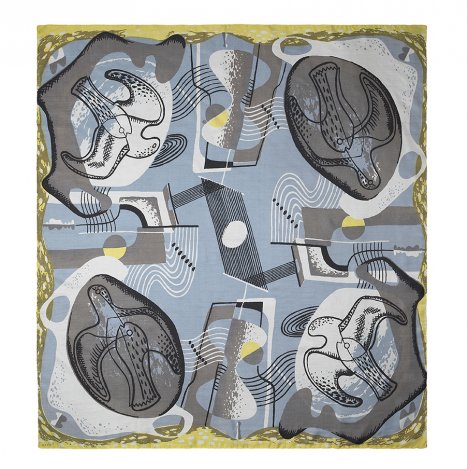

John Tunnard

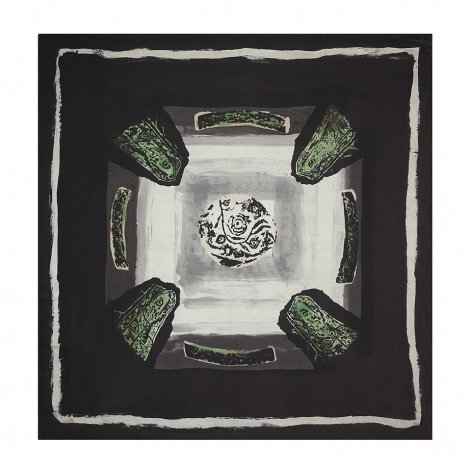

John Piper

Jean Michel Atlan

Jean Hugo

Jean Cocteau

Ivon Hitchens

Henry Moore

Henri Matisse

Gerald Wilde

Françoise Gilot

Francisco Bores

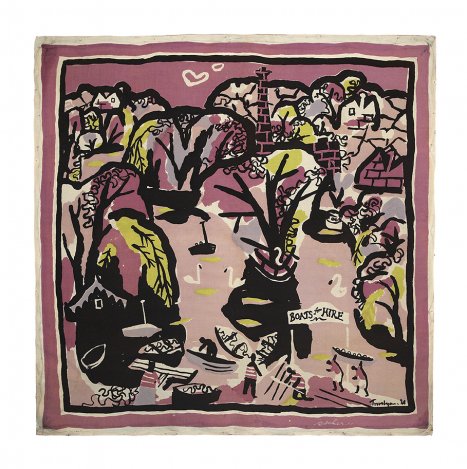

Feliks Topoloski

Christian Bérard

Cecil Beaton

Ben Nicholson

Antoni Clavé

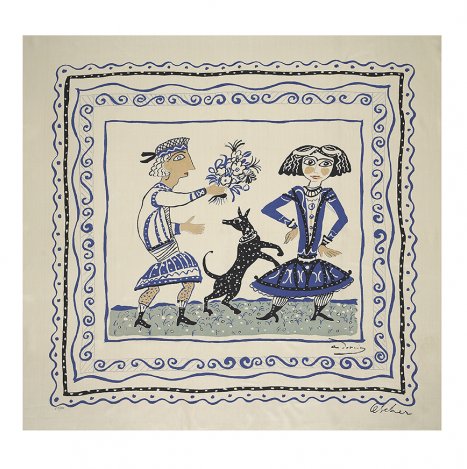

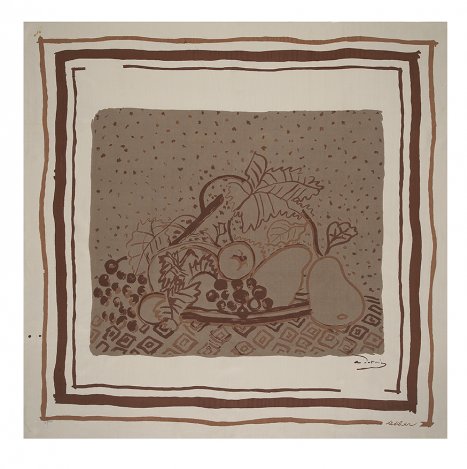

André Derain

André Derain

Alexander Calder

By 1947, Ascher had set up a Paris office in an old gallery space, utilizing frames left behind from the previous tenant to display his squares. By presenting them in this manner, Ascher was likening them to oil paintings and the public seemed to agree, as the noted art critic Sacheverell Sitwell commented after the 1947 show of thirty-seven squares at the Lefevre Gallery: “It is after all, a method by which the sketches of great painters can be brought into many homes in England and abroad…Not a few of these Ascher scarves will be framed upon walls a hundred years from now, for they are among the best and most characteristic products of our day”.

Harper’s Bazaar published an article at the same time noting, “it is a symptom of the real importance of these textiles that they should hang in a gallery of such high prestige.

These squares fall into two quite separate classes. Some are pictures; some are pure designs. But in every single case the artist’s work has been translated with skill and sympathy into terms of fabric. The original sketches have been so carefully worked on that, through all the technical processes of reproduction, the artist’s spirit and quality are retained.

Buoyed by the success of the squares show, Ascher determined to mount a second exhibition the following year of larger works, known as wall panels, which Ascher completed with Matisse and Moore. Matisse’s contributions to the exhibition, Océanie, la mer and its accompanying composition, Océanie, le ciel, occupy a critical position in the artist’s late work.

The genesis of the Océanie project dates to early 1946, when Ascher approached Matisse about designing a fabric wall hanging. Matisse did not immediately accept Ascher’s offer, but asked him to visit again the next time that he came to Paris. When Ascher returned several months later to the artist’s apartment, he found Matisse sitting on his bed, paper and scissors in hand, directing his assistant to pin cut-out shapes directly onto the walls of the room. Two adjacent walls were almost entirely covered with white silhouettes of birds, fish, sponges, coral, and seaweed, which Matisse proposed that Ascher reproduce as a pair of panels.

In addition, Matisse would create two designs for squares and four works for repeating textiles. These screen-printed linen wall hangings represent Matisse’s earliest use of the paper cutout, his most important form of artistic expression during his last years, to create mural-sized compositions. The panels are the first works in Matisse’s oeuvre that draw explicitly upon his memories of a 1930 voyage to Tahiti, the iconography of which would become the mainstay of his late cut-outs.

Matisse wrote to Ascher: “The beauty of the sky, the sea, of fishes and coral plunged me into the inaction of complete enchantment. The local color of the objects was not changed but their reflection seen in the light of the Pacific, gave me a sensation comparable to one that I have experienced when looking into the interior of a large golden bowl, with eyes wide open I absorbed everything as a sponge absorbs liquid. Only today did I remember these marvels with a tenderness and precision, which joyfully enabled me to execute these two panels”.

Moore’s contribution to the 1948 Lefevre exhibition were two large scale panels, Reclining Figure and Two Standing Figures, featuring the same vibrant colors and energetic lines as are seen in many of his textile sketches. The subject matter and overwhelming scale of the two panels is most closely related to Moore’s preparatory drawings for his sculptures. The panels posed similar printing challenges as the squares for Ascher, who was determined to capture the texture which resulted from the interaction of the watercolor over the wax crayon in the artist’s preliminary drawings as well as his varied color palette. Moore himself took an active role in the printing process, visiting Ascher’s studio to carefully inspect each work and to personally sign the pieces.

Concurrent to their work with artists, the Ascher business in the couture textile trade was flourishing. From the late 1940s on, Ascher’s unique take on color and print design also found admirers in such designers as Dior, Balenciaga, Givenchy, and Lanvin. Ascher’s ability to trend set reached its summit in the autumn collections of 1958 when almost every single major designer used the same new innovative Ascher mohair fabric as a focus of their collection.

The Aschers’ work in textiles and art represent the postwar ambition to do something different, something avant-garde. Their vision was to promote optimism in a postwar society that was often dreary and depressing. They were truly Czech textile innovators. The concept of the Ascher Squares-of collaboration between artist and designer, of freedom within an industry that had always been highly structured-was new. No instruction was given, no restriction placed upon creativity. “Make art” was the request, “let inspiration be the guide.” The artists so employed represented a cross-section of Europe itself. They were English, Spanish, Greek, Russian, American, French in a sense, the Ascher Square is both a representation of postwar liberation and the state of art in the whole of Europe at the time.

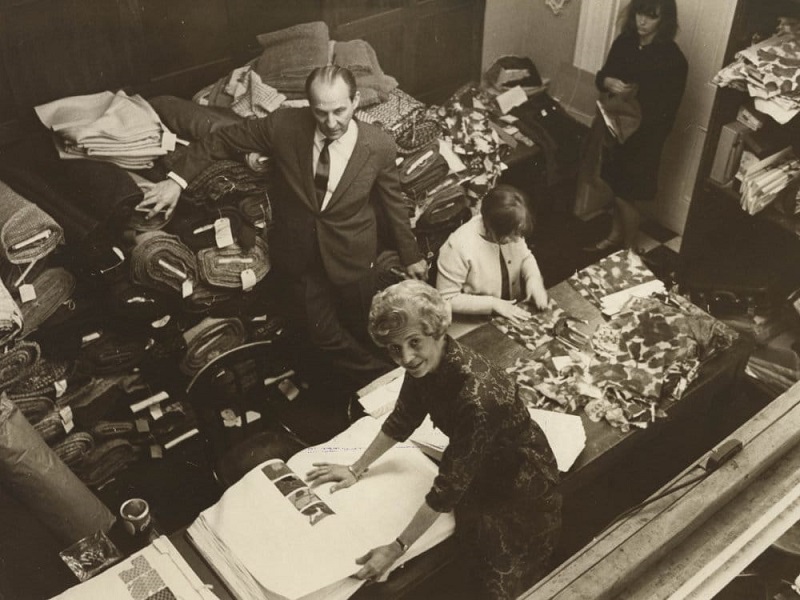

Following on the success of their collaborative scarves, the Aschers were able to set up new, larger premises in the late 1940s, where they continued to produce accent wearable silks in collaboration with artists from across Europe.

The Aschers branched out into floral motifs throughout the 1950s, designing and printing fabrics featuring hummingbirds, flowers, radishes and bees, breathing exuberant life into the British fashion industry and attracting high profile designers including Christian Dior, Cristobel Balenciaga and Yves Saint-Laurent.

Jardin Japonais, afternoon dress Christian Dior, spring/summer 1953, Blue Bird, screen-printed silk. Fabric © Peter Ascher, Ascher Family Archive

In fact, Ascher fabrics were immensely popular from the 1940s to the 1980s, frequently appearing in top fashion magazines, and used by European fashion houses including Chanel, Lanvin-Castillo, Pierre Cardin, Alberto Fabiani, Ronald Paterson, Mary Quant, David Sassoon, and others.

In the 1960s Zika and Lida made further pioneering designs with brilliantly colored and patterned mohair in acid sharp shades of orange and pink, stunning audiences into disbelief with a fabric described by American Vogue as “soft, thick, weightless as a moth’s wing, spun together out of mohair, nylon and wool…”

In the decades that followed the Aschers continued to experiment with bold patterns and unusual fabrics, including the humble cheesecloth, along with chenille, plastic-coated printed cotton and even paper-based textiles, taking an ever-expanding array of experimental risks.

By the 1970s, popularity was so high they were producing upwards of 2,000 scarves a day to keep up with demand.

Watch this two-minute video about these Czech textile innovators:

Ascher’s legacy is governed by their only son Peter. A 264-page book about the work of Ascher and his wife Lida, by Valerie D. Mendes and Frances M. Hinchcliffe, in collaboration with Lida Ascher, was published by the Victoria and Albert Museum (V&A) in London, to coincide with a 1987 retrospective exhibition of the Aschers’ work. The title Ascher: Fabric, Art, Fashion, describes the breadth of their achievements in these three related fields.

Ascher Squares Designed by Matisse, Moore, Derain, Sutherland, Hitchens, Hodgkins, Laurencin, Cocteau and Others is a catalogue, with an introductory essay by by Sacheverell Sitwell, published in 1948.

Ascher: Fabric, Art, Fashion is an illustrated catalog published to accompany an exhibition at the Victoria and Albert Museum, April 15–June 14, 1987, on the textile designs of Zika Ascher and Lida Ascher.

The Museum of Applied Arts in Prague organized a large research and exhibition under the title Šílený hedvábník (in English The Mad Silkman) in March 2019. The pages of The Mad Silkman are filled with pictures of the exclusive designs made for the Aschers, which became both the famous scarves and then printed fabric for the world’s top fashion designers.

Enjoy!

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8.

Thank you in advance for your support…

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

We appreciate you more than you know!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.