Do you enjoy going back in time as much as I do? What if I could take you back to Šumava in 1929? You’d stay in the towns, see the Chod people, experience the marketplace, explore the forest, and learn about the mythology and folk tales. The Šumava mountain range stretches across south and west Bohemia, roughly a two hours’ drive by car from Prague. Although, it is a totally different world—a world of deep forests, ancient towns and medieval castles. Would you delight in visiting this enchanted forest?

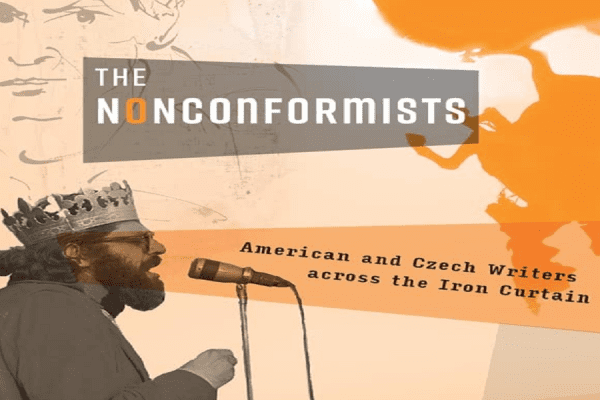

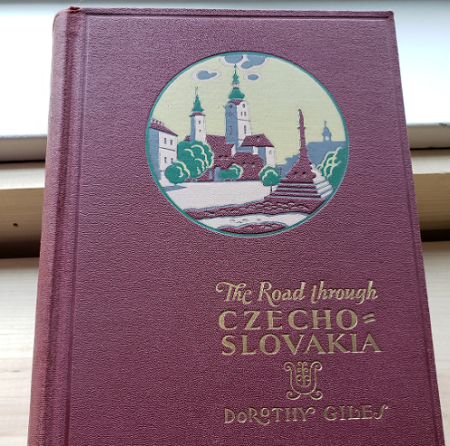

I certainly did when I read this chapter from the book entitled The Road Through Czechoslovakia by Dorothy Giles, 1930. It is a hefty book of 420 pages which takes us on a journey of discovery of the people and places of our homeland. I am sharing the entire chapter here with my addition of photos and footnotes. It’s a long read, so make yourself a cup of tea or coffee, settle in and enjoy…

Dorothy Giles was born on April 27, 1892 in Cold Spring-on-Hudson, New York. She graduated from Cathedral School of Saint Mary, Garden City, Long Island where she studied art and languages. Giles was on the staff of Cosmopolitan Magazine from 1933-1939 and an author. Publications include The Road Through Czechoslovakia, and The Road Through Spain. She was a special writer, editorial consultant and Member American Friends of Czechoslovakia, Pen and Brush. Giles died on December 29, 1960.

Dorothy Giles, was not only an American author, she was a Decorated Knight, Order of White Lion, by President Masaryk of Czechoslovakia – the first woman so honored for recognition of her book, The Road Through Czechoslovakia.

Today I am sharing the entire second chapter of the book, whose subject is the beautiful forest of Šumava, the people of the surrounding villages, history of the battles that took place, and some interesting personalities she meets along the way.

Chapter Two — The Enchanted Forest

Magic place, the Šumava (1). The home of trolls and pixies and those grotesque sprites of wind and fire and water – the ježeniny (2), that whisk through a thousand Bohemian fairy tales—it is the haunt of sprites blest and unblessed, not all of these having been put to captivity by Svatý Prokop (3), that ancient bishop of Bohemia, whose stature, leading a pair of demons on a leash, stands reassuringly over the door of many a parish church on the forests’ fringe.

Photo: Divci Kamen

If any there be who think that these ancient, capricious, disturbing forces no longer exist, that the rusalky (4) whom Princess Teta (5) taught the Czechish folk to placate, are become mere bogeys to frighten naughty children, let him have a care that he himself does not fall into their clutches and forfeit his sight even at such a time as he deems himself the wisest.

Růžena Maturová as the first Rusalka on March 31, 1901, at the National Theater.

It was not yet four o’clock when the Boots knocked me awake. He went with me through the unearthly half light that precedes the true dawn. Even at that hour, the train was filled with county folk. These had evidently been making a night of it in town, to judge from the promptitude with which they fell asleep on the third-class benches amid baskets, bulging linen bundles, even live geese. The approved manner of transporting these fowl would seem to be to bind each one securely in swaddlings of linen cloth which pinion wings and legs, and leave the long necks with the bright eyes and vicious yellow bills to protrude dangerously.

There was also a group of bare-kneed men and women with rucksacks and staffs, bound for a holiday on the trails of the Šumava.

Beyond Plzeň’s (6) modern suburbs with their flat-faced shutterless houses—modern Czech architecture leans to the packing-case type—the rolling plain appeared again with the morning mists curling from it; the floating grey wisps were ghostly reminders of the long veils of the Hussite women which by Žižka’s (7) orders they spread on this same plain to entangle the feet of German soldiery. At Sudoměř (8), here on the wheat lands, was Žižka’s first victory. Legend tells that, as for Joshua the sun stayed its course, so for Jan of the Chalice it sank a full hour before its appointed time, and, in the sudden darkness, he drove the emperor’s forces from the field.

Much of the Thirty Year’s War (9) was waged on the plains of western and southern Bohemia. Plzeň, stronghold of the Catholic Imperial Party, battled Protestant Tábor (10). The two hundred years from the death of Hus (11) in 1415 to the death of the poor Winter King (12) and his English queen (13) at White Mountain (14), are filled with sanguinary campaigns of Czechs against Czechs and both against Austrians and Hungarians.

Day came. We stopped at numberless village stations, mere platforms set down in the everlasting sweep of wheat and clover fields. But each adorned with its boxes of bright flowers as all the railroad stations in the Republic are. The third-class compartments emptied, filled, emptied again. The peasants who left the train knelt on the platform to pull off their boots, stuffed these into their bundles, settle the bundles onto their backs, the trudged away, comfortably barefoot, through the dust.

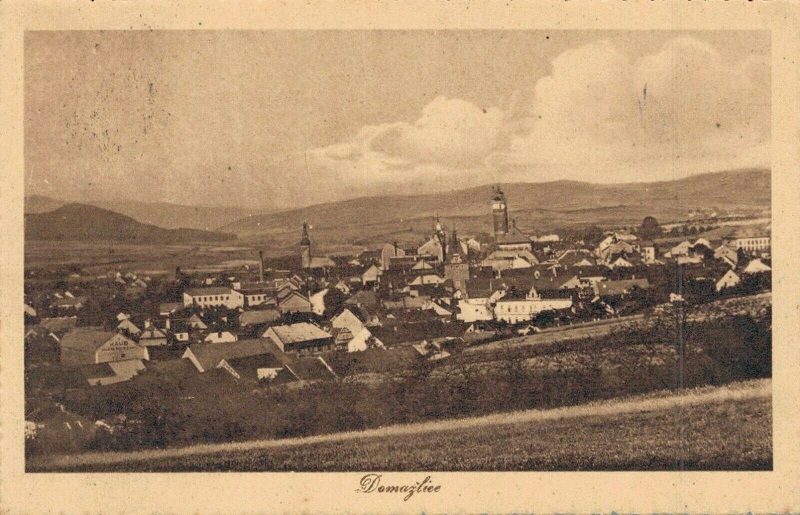

At last, lying dark on the horizon, the curve of the forest. And rising against the wood two strong white towers and the red roofs of a town—Domažlice (15) of the Chods (16).

Domažlice.

Domažlice means the Town-of-the-Stay-at-Homes. Just as Chod means One-Who-Walks. On the heights that overlook Bavaria and Bohemia, the Chod clansmen guarded Wenceslas’ (17) kingdom from their hereditary Teuton (18) foes. Their flaming beacons, visible, it is said, as far as Plzeň and Karlův Týn (19), where the sceptre and crown on Wenceslaus were kept, gave warning of invasions.

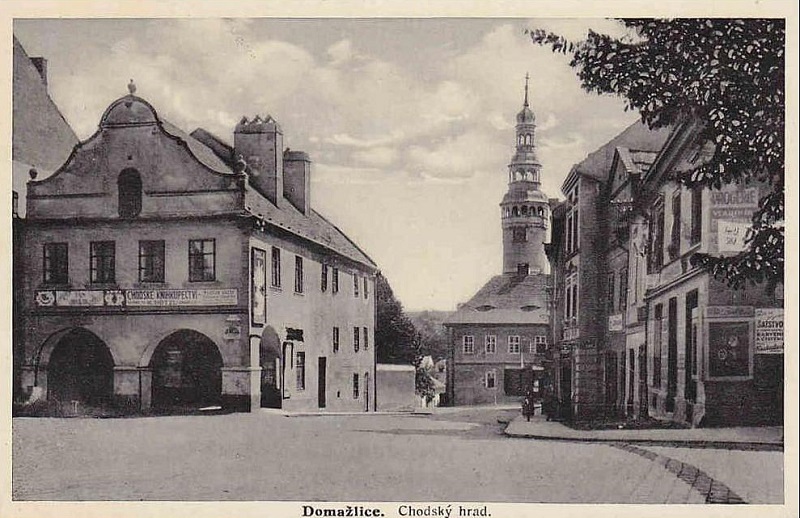

Chodský Castle, 1901.

In return for their service as sentinels, a ninth century privilege—the yellowed parchment is still to be seen in the town museum—relieved the Chods of military service. A not inconsiderable reward, considering Bohemia’s bellicose history. Their tribal banner, with the head of a snarling watchdog, still flutters on great days from the battlements of Chodsky Hrad (20) on the town’s edge.

One must walk the straggling dusty road that leads from the railway to the town gate with its deep arch and the arms of the city above it – arms in which an angel adds his supernatural strength to the resistance of two fortified towers. Homely little shops with pots of red geraniums in their windows nestle against the tower’s battle-scarred stones. They were open, that Sunday morning, and doing a thriving trade in round, sugar-coated koláčes (21) and painted gingerbread, and the hard little green pears that young Czechs and old seem to devour with a national immunity to stomach aches.

Women at the Domažlice Market show off their koláče, Šumava.

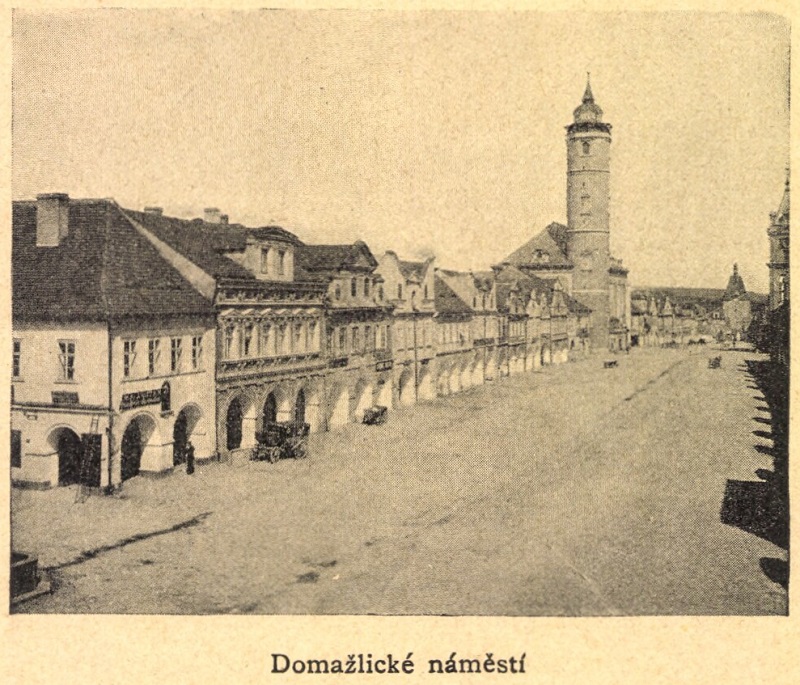

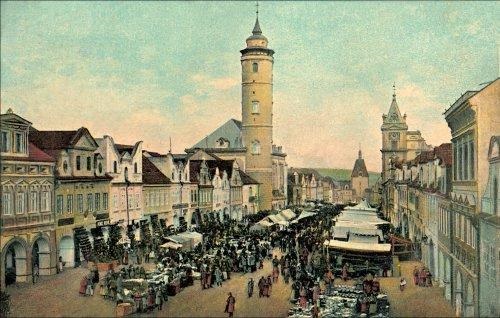

Within the gate, one is at once in the greatest náměstí (22), bordered on three sides by deep arcades upheld by massive-like, strict-minded burgesses leaning forward, propped on stout elbows, to watch the life of the market place.

Town square in 1903.

Gothic doorways, groined and keyed with chipped armorial bearings, now hidden under many layers of republican whitewash, lead from the arcaded street to dwellings and shops.

Chodsky Castle

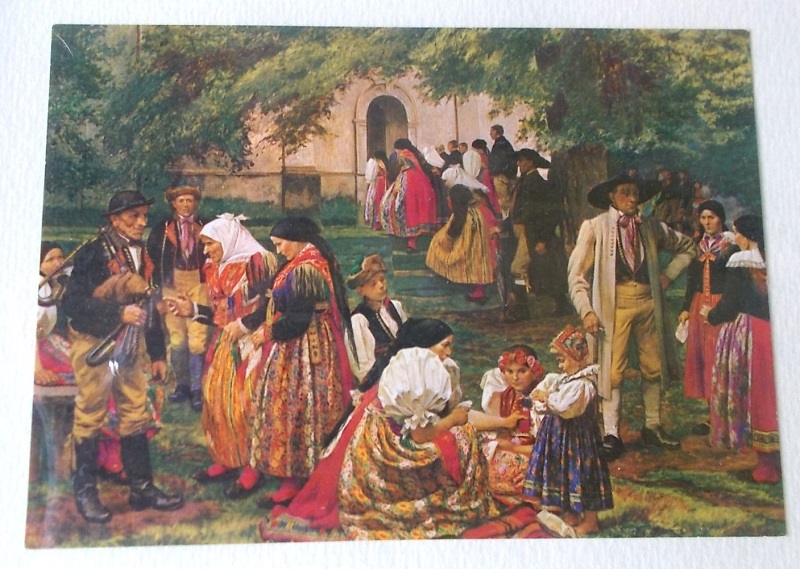

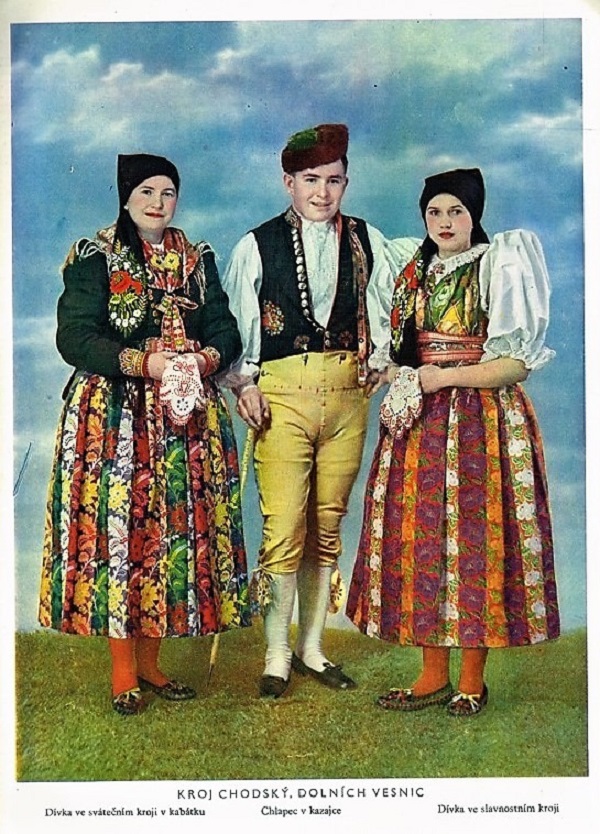

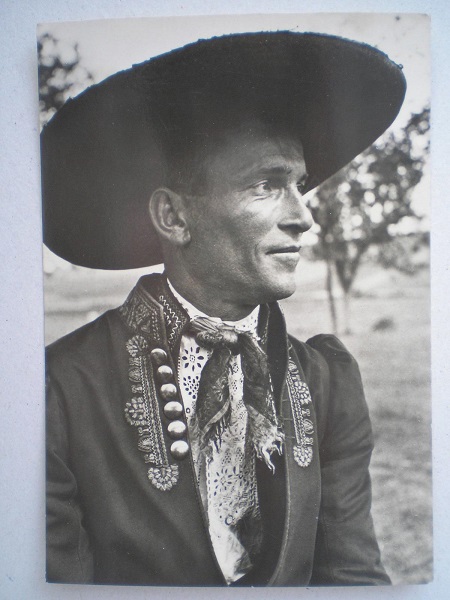

On Sunday morning, when the town’s pulse beats its quickest, the whole effect is strangely oriental; the cool depths of the arcades, where the sellers of cheeses, hot sausages, fruits, painted gingerbread, poppyseed and bundles of dried herbs spread their wares ; the great sun-splashed square, ablaze with lengths of scarlet calico and rows of scarlet stockings on the booths of the travelling merchants; the strolling groups in their distinctive Chod dress—the men in fawn-colored, knee-length trousers, with fine embroidered blue waistcoats over their full-sleeved, white linen shirts—the women scarlet-skirted, scarlet-stockinged, in tight-sleeved, scarlet bodices, their black kerchiefs tied at the nape of the neck and one embroidered end flung proudly over the left breast.

Chod people at a church gathering.

And keeping watch and ward over all, the two tall, round, fortified towers ; that of the church on the right, and the castle’s on the left.

And all this glory of scarlet, all the sizzling of sausages and chiming of church bells, all this peacocking and lovemaking and gossiping under the arches, ends as irrevocably as Cinderella’s ball at the stroke of the clock.

Chod people in traditional dress.

An hour after Mass is over, the square is deserted. The shutters are put up at the shop windows, in the braziers the charcoal is reduced to a heap of ashes.

Chodové | October 1895 by E. Strouhal

Shriven and blessed, and with the week’s provender securely tied in the bundles on their backs, the Chods have gone back to their hills.

Loitering under the arcades are only a few old men, townsmen all, smoking their ruminative, long-stemmed pipes with the painted porcelain bowls and dangling green tassels.

Domažlice, undated. Author not specified. Stored in the archives of Martin Wágner.

It is so in all the country towns of Slavdom (23). You must catch them at the flood. On Sundays and on the days of weekly and more bustling monthly markets, they are ablaze with costume, their streets quick with life.

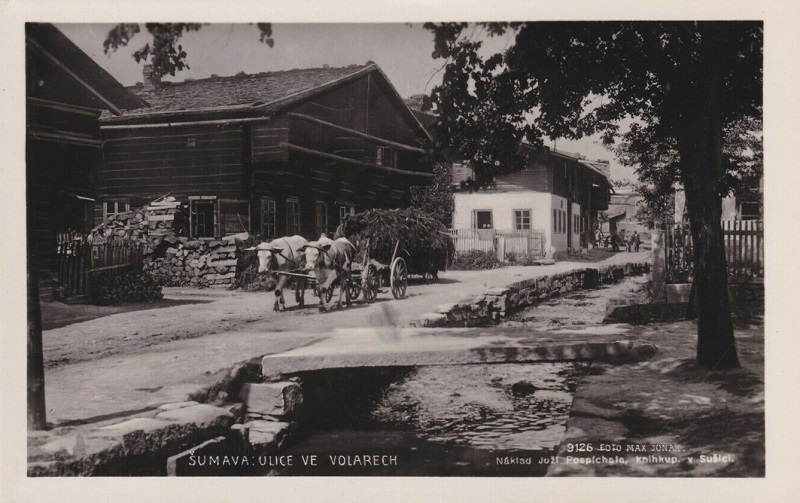

Šumava in 1929 – The Enchanted Forest

At all other times, they are strangely dispirited. No crowd comes running to gather about the casual stranger, as is the lighter way of Latin towns. The traveller comes and goes, and shrugs his shoulders over the waning picturesqueness of Central Europe. If one would know the true life of these people, one must follow the weekly markets, just as in rural England one runs away from the early-closing days. And Sundays become days of excursions and adventures.

Domažlice was the home of the Czech novelist Božena Němcová (24). Her novel, “The Grandmother,” (Babička, 1855) is one of the classics of Bohemian literature.

An hour’s walk out of Domažlice brings you to the height of Újezd (25) where stands the statue of the Chod hero, Jan Sladký (26). More usually he is called simply “Kožina,” after the freehold that he farmed.

When the Hapsburgs (27) revoked the ancient rights of the Chods, Kožina led the clansmen in revolt. The uprising was summarily put down, and the leader was hanged in Plzeň’s market place. His story forms the theme of Jirásek’s (28) novel, Psohlavci (The Dogheaded, 1884) from which is drawn the opera which is so popular with all Czech audiences.

The black embroidery which ornaments the collars of the Chod costume to this day is a mark of perpetual mourning for their hero.

The tower gate guards the entering in of Domažlice from the plain. From the opposite end of the náměstí—one has recourse perforce to the Czech name, since so few of these market places are square ; the majority being like Domažlice’s, a tapering oblong—a sign post put up by the Czech Tourist Club (29) pointed me to the forest.

The market place dwindles into a street with a row of pollarded sycamores shading the rosey, old house gables ; the street in turn dwindles into a country road shaded inadequately with rows of distorted plum trees. The road becomes a path.

A path in the Šumava Forest today.

The forest came forward to meet it, and took me into its dark embrace.

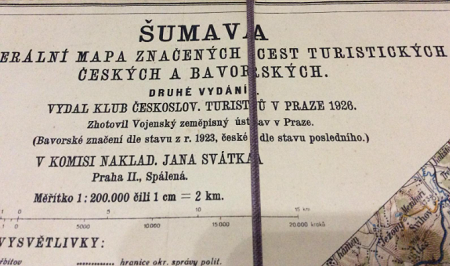

It was early when I started, fortified with a map and guide to this part of the Šumava. The Czech Tourist Club publishes these little booklets, one for each section of the republic that is walkers’ ground. They give all the trails, the distances, the locations of refuges where food and emergency accommodations may be had, and the significance of the painted blazes that mark the paths.

My little map, bought in Domažlice from the knihkupecs—the literary tradition which decrees that all booksellers shall be eccentrics would seem to have evolved the Czech name for the profession—showed innumerable paths leading across the Pass to Bavaria. How much Bohemian history has poured through that cleft between Český les (30) and the Šumava! Chod beacons flaming on the heights again and again to warn Prague of the ever dreaded German advance. When Žižka won his celebrated “Victory” of Domažlice, the defile was packed with the retreat of the German Catholic forces. Pell-mell, foot and horses, master and man together, they thronged the narrow way. The Pope’s legate, Henry of Winchester (31), the son of an English king with the blood of Agincourt (32) in his veins, tore the shamed battle standard from the bearers and hurled it beneath his horse’s hoofs in disgust.

My way led not over the Pass but eastward, along the inner edge of the Šumava which curves from Domažlice in a southeasterly direction to Český Krumlov (33), a distance of some fifty-six English miles. Two peaks read their heads from the forested granite ridge ; Javor (34) on the Bavarian side, and Bohemian Boubín (35), standing four thousand feet above Prachatice (36).

Šumava people working in the forest together.

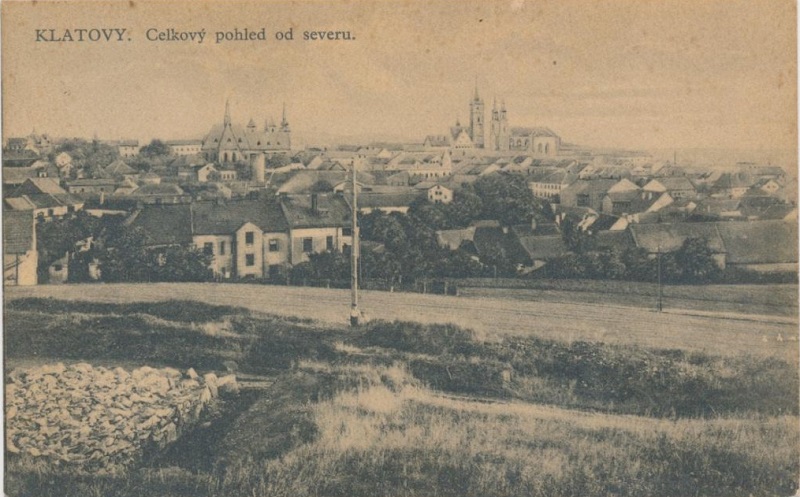

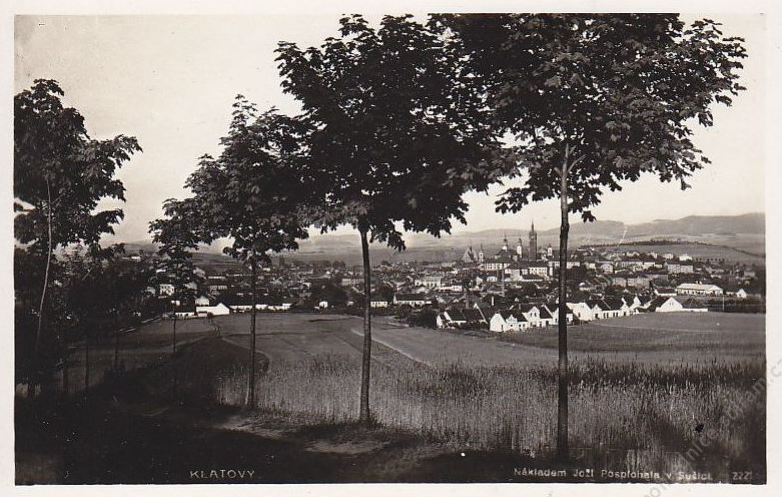

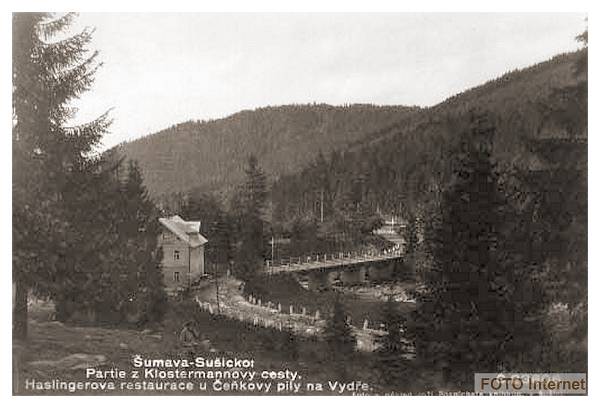

I had no thought to go so far, though the Guide held out alluring suggestions for walking trips of four days and more, with opportunities to stay overnight in the klostermann huts (37) maintained by the Tourist Club ; only to Klatovy (38), a town described in high terms both for its “architectural memorabilia” and the comfort of its Inn of the White Rose (39).

Klostermann Mountain Hut is the work of architect Bohuslav Fuchs. It was built in 1924 as a Czech Tourist Club mountain hut for tourists.

Klatovy lies from twenty miles east of Domažlice. By sending my luggage ahead by train, and making an early start I might expect to reach U Bílé růže by nightfall.

Every forest is a world of its own, a complete and separate universe into which the things of the open have no right of entry. And all are different. These vast tracts of the Šumava in which millions of trees have seeded, sprung up, flourished and crashed to their fall to become in turn fodder for new green generations, has been protected for more than a thousand years.

It is not wild at all, the Šumava. It has none of the lusty vigor, the exuberant, pushing growth of the Maine and Michigan woods ; it lacks the lonely exaltation of the high timber lands of our American Northwest. It is stately and ordered.

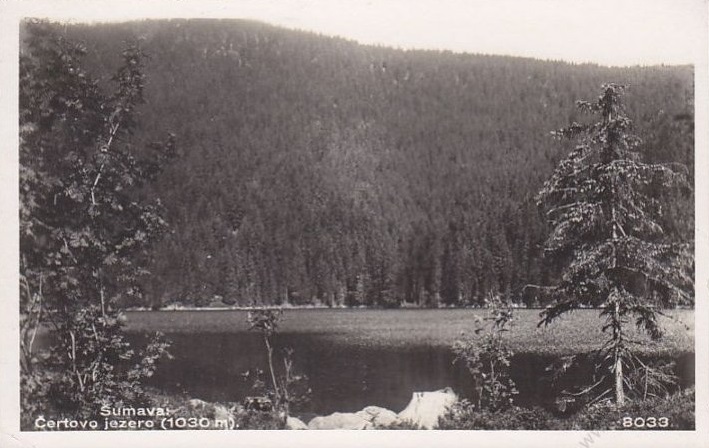

It marshals its serried files of spruce and pine as its overlords marshalled their armies. It knows no revolt, no sudden temperamental moods of dells and ravines, or open barren spaces. The brooks that rush through it to become rivers to water Bohemia—brooks well stocked with trout, but woe to the tourist who would poach their waters—tumble into picturesque waterfalls, or steal away into still black tarns.

No, the Šumava is incredibly, incurable romantic. It is a picture book forest, a setting for a Tennysonian Lady Clares and Lord Ronalds (40) ; a terrain of Andrew Lang (41) adventures.

It was wonderfully still, that day, as I walked there. No birds sang ; not a rustle betrayed the presence of the summer wind. The thick carpet of dried needles was delightfully springy under foot. The path’s edge was outlined in pale grey mosses, and here and there buttons of tiny orange and red mushrooms.

The Guide spoke warningly of the danger of wandering from the paths ; it threatened peat bogs and bottomless lakes. Being written no doubt, for literal, sober-minded tourists intent on mileage, it made no mention of the ježeniny who are known, by those wise in forest lore, to lie in wait for foolish travellers to rob them of their eyes. It marked the lakes and springs, but gave not a single paragraph to the water sprite who dwells therein. The Šumava water sprite has a fondness for appearing to maidens in the guise of a monster frog. He croaks his wooing and when he prevails, leads the enchanted damsel down under the waters to his palace. There he shuts up her soul in one of the apothecary jars that line his shelves and returns to the water’s edge too await another bride (42).

It was close on noon, and I figured that I had walked more than half my journey, when the quick barking of a dog gave warning of habitation.

Around a turn of the path I came on a clearing—and a cottage. It might have been one of those rustic barometers with Fair Weather in a blue apron, and Storm in a yellow bodice, popping in and out of its door by turns.

On a bench beside the door sat a forester in his proud green livery with the chamois brush in his hat.

Typical Czech Forester, Šumava in 1900s.

The dog’s bark was not fierce but welcoming, and the forester rose and beckoned me to a seat on the bench. His daughter came from the cottage and the two questioned me, turn and turn about, in German, who I was, whence I had come, and whither I was bound.

Cottage in Šumava.

The forester was a lean grizzled veteran of the forest ; the girl , tall and straight and lovely in her blue skirt and white linen blouse with the shirt full sleeves. Her head was unbound by any kerchief and the long virginal braid fell across her shoulder. As she leaned against the dark frame of the cottage door, she was like a shaft of sunlight that had found its way to the forest’s heart.

In response to their questions, how I, a stranger, hoped to find my way in the Šumava, I showed them the map and guide. The forester handled them scornfully.

“There is more in the Šumava than is set down here,” he said. “I have lived here all my life ; my father and my grandfather were huntsmen for the Prince Swartzenberg (43). But even I do not know all that the forest holds. Even they did not know.

Perhaps you have heard the story of Helen’s castle?”

I shook my head.

“It happened a long time ago. Our Bohemian King Henry had a daughter named Helen. She was very beautiful. The king wanted to marry her to the king of Hungary. But Helen loved a young count, Graf von Altenburg. He was not royal, you see, but he was very clever. While the king was away at the wars, the Count came here to the forest. He built a castle. It was the most wonderful castle in the world, finer even than Karlův Týn. You have seen Karlův Týn?”

“Not yet,” I said.

“Ah, well, this castle was still stronger and more beautiful. Finer than the great house of the Swartzenbergs (44) in Český Krumlov. The Count fitted it with furniture all of gold and jewels. He stocked the pantries with food, and the cellars with wine. Then, that no one should know where the caste stood, he killed all the workmen who had done the building. When all was ready he brought the Princess here.

“They were very happy in the forest castle, just those two together. They hunted the stag and they fished for trout in the streams. And at night they went back into the castle and drew up the drawbridge and slept in safety.

“Then one night, a wayfarer knocked at the castle gate. He was an old man so they let him in. They did not now that it was really King Henry come hunting his daughter. They even asked him about the king.

“‘He is dead,’ said the old man, craftily.

“And Helen clapped her hands and cried for gladness.

“The old man who was her father and the king said nothing ; only listened.

“In the morning he went away. But he came back. Oh yes, soon. With a great army. He besieged the castle and broke down the wall, and set fire to the towers. Helen and the Count fell on their knees and cried to him to spare them. At last he did. He took them away to Prague, and it is said that Helen never laughed again. But the castle was destroyed, and no man to this day can tell you where it stood.

“Now, there is something not in your book,” he finished.

“It’s a fairy tale,” his daughter said.

Her words, or perhaps the presence of her ripe loveliness stirred some resentment in him. “She wants to leave the forest,” he said harshly. “She is not happy here.”

“I go to be married.”

“Married,” the forester snorted. “To a cutter of pearl buttons. A man who comes and goes, and eats and lies down when a whistle blows. To a townsman who lives in a cottage for which you must pay rent. And then he has not it all to himself!”

The girl’s lip curled proudly, but she made no reply.

+ + + + +

I came into Kaltovy on the path of the sunset. The last kilometer lay across fields of carnations. The growing of these flowers is Kaltovy’s chief industry. There were women and girls at work in the rows of silver-leaved plants. They straightened as I passed and regarded me gravely.

The glory in the west touched the little town’s two towers—the Black Tower of the lords of Rožmberk (45), long ago owners of the Šumava, and the White Tower of Panny Marie, by which Klatovy is saved now and through eternity.

The Guide, whatever the forester may have thought of it, had not erred about Klatovy. The town has a fine stone-paved square with a fountain and rows of fourteenth century houses that lift towering gables as though hopeful of attaining the grandeur of the two towers, and the Bílá růže.

From Klatovy, forest trails lead over the ridge of the Šumava to Železná Ruda (46), the frontier town, and thence down to St. Florian’s Abbey (47) on the Danube near Linz (48), an establishment so rich that the bankers of Genoa were content to accept it as security for the three million crowns they loaned Maria Theresa (49) for her war against Frederick the Great (50). Florian is a much sought patron in the wooden villages of the Bohemian forest. One passes many a cottage with a niche over the door wherein stands a statue of the saint with his two brimming water pails. And over his head in its Roman helmet that has furnished Czech fire companies with a model headgear, the verse:

House and home trust I to Forian’s name ;

If he protect it not, his be the shame.

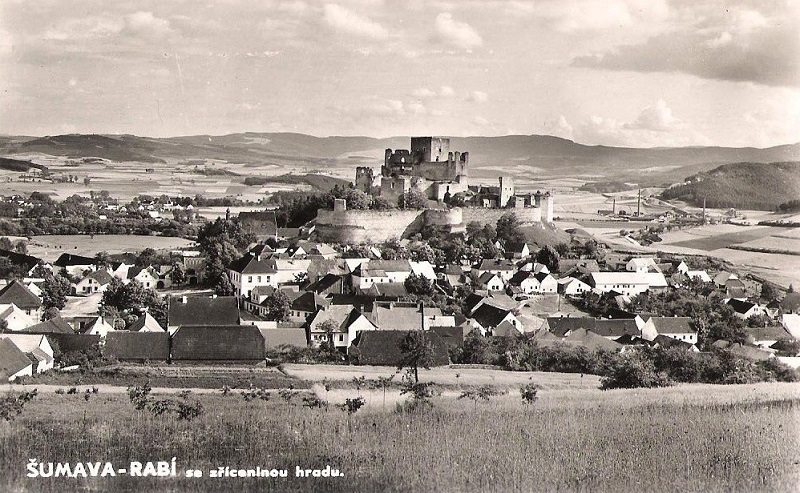

A railroad skirts the forest running from Domažlice across southern Bohemia to join a network of other lines at Brno in Moravia. There is also a complexity of local motor buses linking village and village. But by no amount of juggling of train and bus schedules could I work out a way of leaving Klatovy in the early afternoon, stopping off at Sušice (51) to visit the ruined fortress of Rabí (52), and continuing to Písek in the evening.

Sušice in Šumava.

The Bílá růže’s proprietor, the porter, the waiter and his imp, and two or three habitues of the inn’s combination coffee house and billiard saloon, which serves the town as a men’s club, agreed unanimously that I must depart from Klatovy by automobile.

Equally unanimous was the verdict that the automobile should be that of Antonín Šrámek. The imp was dispatched in one direction, the porter girded his green baize apron tighter about his loins and set forth in another, to find Antonín and his car.

Produced, Antonín proved to be a worn-looking little man whose age might have been anywhere between thirty and fifty. He seemed to wear habitually a puzzled expression. His eyes, deepset under overhanging brows, were intent on some secret search. They did not look out, but in. He accepted me, my luggage and destination without question, except to ask whether I was prepared to pay the charge of two and a half crowns a kilometer for his solitary return drive to Klatovy while I went on by train. Reassured as to this, he sighed deeply, cranked his engine and with deep bows from the group at the Bílá růže’s door, we started.

The road, white and dusty, stretched across the fields to the southeast. The July sun blazed on the golden wheat stubble where old women gleaned.

Here and there in the patches of clover the mowers were whetting their scythes, preparatory to cutting the green growth and piling it to dry on the dead spruce trees set up in each field. To the left of us, as far as the eye could reach, stretched the alternating narrow green and gold and brown stripes that are the result of division and redivision of the peasants’ land holdings. On our right, beyond narrow fields, lay the forest.

I thought with longing of its cool dark paths ; the invigorating fragrance of its breath. I spoke of this to Antonín.

He nodded, understandingly. He was himself forest born, he informed me. He had come from the old town of Vimperk (53) where the press still turns that printed battle Bibles for the Hussites in 1484.

“And are there ježeniny in the forest there?” I asked lightly.

There were many who thought so, he said. Forest dwellers were apt to be superstitious. He had known men who refused to go into Šumava without a sprig of bramble in their hats. The bramble, the avowed, would ward off the most dangerous ježeniny.

Stožecká kaple by the legendary Šumava photographer Josef Seidel.

Others, more pious, trusted to the stump of a church candle carried in the pocket. But these, I must understand, were all ignorant persons, without education. They accepted without question all that the old people and the priests told them. He, Antonín Šrámek, was neither Catholic nor Protestant. A liberal, a free thinker ——

The plain dipped suddenly, and we sped through a whitewashed, deep-thatched village set between green grass walls. The women were washing linen in the trickle of muddy water than ran down the middle of the straggling street ; flocks of geese fled squawking from before our wheels.

Czech geese in Šumava.

The road lifted, mounted the plain again. Before us stretched the forest, and against the forest, on a barren shoulder of hill rose a shattered silhouette of grey bastions and towers. Antonín pointed his finger, “Rabí.”

We left the car in the village at the base of the hill where the castellan gave us the key and pointed to his embonpoint and the mug of beer awaiting his consumption as excuse for not accompanying us. The drive, stone-paved under the grass of centuries of disuse, leads steeply to the gate. Rugged and lonely, the old fortress rears its shaggy head above the village’s small concerns.

Rabí Castle in 1708.

Samo (54), chief of the Slavs, built the first citadel here in the seventh century, when he battled Dagobert (55), king of the Franks (56), and forced him to recognize the Šumava as the boundary between the two empires. The present castle, all that remains of it, dates from the thirteenth century.

Today, only broken stones testify to the height of its towers, the impregnability of its walls. Two moats, the inner one tumbled into the rock of the hill site, gridle the fortress. Within these, gates and courtyards, great subterranean dungeons and treasure chambers, a chapel with delicate window looking to the east, and the ruins of the Knights Hall tell the story of the past. Here, no doubt, the Minnesingers (57) struck their harps and sang the ballads of the Niebelungen (58). Here came fast-riding couriers from Crécy (59), bringing news of their King John’s (60) death, and the Black Prince (61) of England, taking for his shield the motto and device that had been Bohemia’s. Here, relaxed after supper, wandering friars, well-lined abbots, troubadours and captains of mercenaries recounted the gossip of Carinthia (62), Württemberg (63), Burgundy (64), and Provence (65). Here men slapped their sides over the latest escapade of the Tyrol’s Ugly Duchess (66) ; muttered their suspicions of the black magic practiced by the Jews ; toasted, hands on a sword hilts, the Maid of Orleans (67).

Rabí was a Rožmberk fortress when Žižka led his troops to besiege it. An arrow from the parapet cost the Hussite leader his left eye. “Old rhinoceros Žižka,” to quote Carlyle’s (68) phrase, was a son of the Šumava, born in the enchanted forest.

National park Sumava in Czech Republic

“He was the greatest general,” said Antonín Šrámek suddenly. “Greater than Napoleon (69).”

It was then I thought to ask him about the War.

“Yes,” he said simply. “For seven years I fought. Four times I was wounded. When the War came, the Mayor stood up in the square. He said we Bohemians were of Austria, and we must defend our fatherland against the Italians. We went away south to fight. In the mountains. It was hard there in the snows. The mountains are not like our mountains. The forests, too, are different. My company was with the Hungarians. But they were good fellows in their way. When things were very bad, Kaiser Karl (70) came to visit us. He said that we were all Austrians and soon the War would be over, and we would go back to our homes and all would be well.

“Then there was peace. An officer came from Prague. He said that we Czechs are not Austrians any more. He said that we must defend our fatherland against the Hungarians. They sent us away to Slovakia, to the Carpathians, to fight the Hungarians. For three years there I fought the men who had been my comrades. It is hard to understand…”

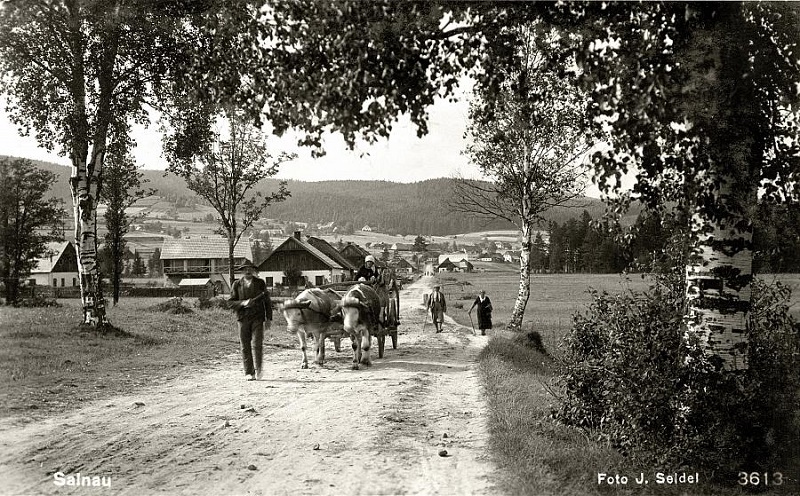

Historic photo from Salnau (now Zelnava) in Šumava.

The sun had dropped behind a shoulder of the Šumava. The shadow of the forest fell on us.

I looked at Antonín Šrámek. He had taken off his hat and he stood there twirling it in his hand. The old cloud of bewilderment had settled again on his face. His eyes continued that secret inner search.

Is it only in the enchanted forest that the ježeniny lie in wait to rob men of their sight? Only in the fairy tales that false voices lure and betray?

I looked at Antonín Šrámek’s hat. No, there was no sprig of saving thorn.

If you loved this, you will certainly enjoy these other posts we’ve created:

The Ancient Bohemian Forest Known as Šumava

Tomáš Holý in the Bohemian Forest – Trilogy of Films

Šumava National Park (The Bohemian Fairytale)

Poledník Lookout Tower – Then and Now

Or perhaps a short documentary, Our Šumava, with English subtitles:

Footnotes:

1) Šumava (aka Bohemian Forest) – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C5%A0umava_National_Park

2) Ježeniny also Jeziňky – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/The_Jezinkas

3) Svatý Prokop – Saint Procopius of Sázava was a Czech canon and hermit, canonized as a saint of the Catholic church in 1204.

4) Ruslaka – In Slavic folklore, the rusalka is a typically feminine entity, often malicious toward mankind and frequently associated with water, with counterparts in other parts of Europe, such as the French Melusine and the Germanic Nixie.

5) Princess Teta – Daughter of Croccus, Sister of Libuše (Princess of Bohemia), Kazi (Princess of Bohemia), and Libuse van Bohemen

6) Plzeň – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Plze%C5%88

7) Jan Žižka – Jan Žižka z Trocnova a Kalicha was a Czech general – a contemporary and follower of Jan Hus and a Radical Hussite who led the Taborites. Žižka was a successful military leader and is now a Czech national hero. He was nicknamed “One-eyed Žižka”, having lost one and then both eyes in battle.

8) Battle of Sudoměř – The Battle of Sudoměř was fought on 25 March 1420, between Catholic and Hussite forces. The Hussites were led by Břeněk of Švihov, who was killed in battle, and Jan Žižka, whose forces proved victorious.

9) Thirty Years’ War – The Thirty Years’ War was largely waged within the Holy Roman Empire from 1618 to 1648. One of the most destructive wars in European history, it caused an estimated 4.5 to 8 million deaths, and some areas of Germany experienced population declines of over 50%.

10) Tábor – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/T%C3%A1bor

11) Jan Hus – Jan Hus, sometimes anglicized as John Hus or John Huss, and referred to in historical texts as Iohannes Hus or Johannes Huss, was a Czech theologian and philosopher who became a Church reformer and the inspiration of Hussitism, a key predecessor to Protestantism, and a seminal figure in the Bohemian Reformation.

12) Winter King – Frederick V was the Elector Palatine of the Rhine in the Holy Roman Empire from 1610 to 1623, and reigned as King of Bohemia from 1619 to 1620. He was forced to abdicate both roles, and the brevity of his reign in Bohemia earned him the derisive sobriquet “the Winter King”.

13) Elizabeth Stuart, Queen of Bohemia – Elizabeth Stuart was Electress of the Palatinate and briefly Queen of Bohemia as the wife of Frederick V of the Palatinate. Because her husband’s reign in Bohemia lasted for just one winter, Elizabeth is often referred to as the “Winter Queen”.

14) White Mountain (Bílá Hora) – The Battle of White Mountain was an important battle in the early stages of the Thirty Years’ War. It led to the defeat of the Bohemian Revolt and ensured Habsburg control for the next three hundred years. It was fought on 8 November 1620.

15) Domažlice – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Doma%C5%BElice

16) Chods (Chodové) – The Chodové (Chods, “Walkers”, “Patrollers” or “Rangers”) are an ethnic group living in western Bohemia. Today, the Chodové live in an arc of villages near the western border of the Czech Republic, including major population centers in Domažlice, Tachov and Přimda.

17) Wenceslaus – Wenceslaus I, Wenceslas I or Václav the Good was the duke of Bohemia from 921 until his death probably either in 935 or 929. His younger brother, Boleslaus the Cruel, is commonly considered the perpetrator of Wenceslaus’ assassination by the Czech public and the Roman Catholic Church.

(18) Teuton – The Germanic peoples were historical groups of people that once occupied Central Europe and Scandinavia during antiquity and into the early Middle Ages.

19) Karlův Týn (aka Karlštejn) – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl%C5%A1tejn

20) Chodsky Hrad – https://www.domazlice.eu/o-domazlicich/pamatky/pamatky-v-domazlicich/chodsky-hrad-v-domazlicich-243cs.html

21) Koláč (Koláče, plural) – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Kolach_(cake)

22) Náměstí – A town square in an open public space, commonly found in the heart of a traditional town but not necessarily a true geometric square, used for community gatherings.

23) Slavdom – 1: the whole body of Slavs, 2: the area inhabited by or under the influence of Slavs.

24) Božena Němcová – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Bo%C5%BEena_N%C4%9Bmcov%C3%A1

25) Újezd (okres Domažlice) – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C3%9Ajezd_(Doma%C5%BElice_District)

26) Jan Sladký Kozina was the Czech revolutionary leader of the Chodové peasant rebellion at the end of the 17th century. Jan Sladký Kozina was first named Rosocha, after Rosoch Farm, which from 1632 had belonged to his grandfather, and on which he was born and grew up.

27) House of Hapsburg – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_Habsburg

28) Alois Jirásek was a Czech writer, author of historical novels and plays. Jirásek was a high school history teacher in Litomyšl and later in Prague until his retirement in 1909. He wrote a series of historical novels imbued with faith in his nation and in progress toward freedom and justice.

29) Czech Tourist Club – Czech Tourist Club (Czech: Klub českých turistů, KČT), known also as Czech Hiking Club was created in 1888. With over 40,000 members, it is a large organization responsible for maintaining the dense Czech Hiking Markers System. The first long-distance tourist route through the Czech Republic led through Brdy to Šumava and was marked by the Czech Tourists Club in 1912.

30) Český les aka Upper Palatine Forest https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Upper_Palatine_Forest

31) Henry of Blois often known as Henry of Winchester – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Henry_of_Blois (The author has this wrong as Henry of Winchester lived 1096-1171 and she’s discussing events which took place some 300 years later.)

32) The Battle of Agincourt was an English victory in the Hundred Years’ War. It took place on 25 October 1415 near Azincourt, in northern France.

33) Český Krumlov – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C4%8Cesk%C3%BD_Krumlov

34) Velký Javor – The highest mountain in the Šumava and Bavarian Forest.

35) Boubín is a 1362 m high hill in the South Bohemian region of the Czech Republic. It is 3.5 km east of Kubova Huť village. Most of the hill is covered by a primeval forest called Boubínský prales which has been a natural preserve since 1858.

36) Prachatice – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Prachatice

37) The cultural monument Klostermann’s Cottage was built in 1924 by the Czechoslovak Tourist Club. The cottage was named after the writer Karel Klostermann, who allegedly tapped the foundation stone. The newly renovated building offers great cuisine, relaxation and entertainment. Klostermann’s cottage is located in the very heart of Šumava , in the picturesque village of Modrava (990 m above sea level). Its location is ideal for cross-country skiing in winter, when a number of cross-country trails are maintained by machine, and in summer for cycling and hiking. Source: https://www.kudyznudy.cz/aktivity/klostermannova-chata-modrava

38) Klatovy – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Klatovy

39) Inn of the White Rose, U Bílé růže – An interesting change of hands and history to this location. http://klatoviny.blogspot.com/2021/03/klatovske-hotely-i-u-bile-ruze-u-mesta.html

40) Alfred, Lord Tennyson, 1st Baron Tennyson (1809 – 1892)was an English poet. He was the Poet Laureate during much of Queen Victoria’s reign. Lady Clare and Lord Ronald were characters in his work.

41) Andrew Lang (1844 – 1912) was a Scottish poet, novelist, literary critic, and contributor to the field of anthropology. He is best known as a collector of folk and fairy tales.

42) Although she does not name him, the author is writing about Vodník. He stores the souls in teapots. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vodyanoy

43) Karl Philipp, Prince of Schwarzenberg -https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Karl_Philipp,_Prince_of_Schwarzenberg

44) Swartzenberg – The House of Schwarzenberg is a German (Franconian) and Czech (Bohemian) aristocratic family, and it was one of the most prominent European noble houses. The Schwarzenbergs are members of the German nobility and Czech nobility and they held the rank of Princes of the Holy Roman Empire. The family belongs to the high nobility and traces its roots to the Lords of Seinsheim during the Middle Ages. The current head of the family is Karel, the 12th Prince of Schwarzenberg, a Czech politician who served as Minister of Foreign Affairs of the Czech Republic. The family owns properties and lands across Austria, Czech Republic, Germany and Switzerland. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/House_of_Schwarzenberg

45) Rosenberg family – The Rosenberg family (Czech: Rožmberkové, sg. z Rožmberka) was a prominent Bohemian noble family that played an important role in Czech medieval history from the 13th century until 1611. Members of this family held posts at the Prague royal (and later imperial) court, and they were viewed as very powerful lords of the Kingdom of Bohemia. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rosenberg_family

46) Železná Ruda – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/%C5%BDelezn%C3%A1_Ruda

47) St. Florian Monastery – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/St._Florian_Monastery

48) Linz – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Linz

49) Maria Theresa – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Maria_Theresa

50) Frederick the Great – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Frederick_the_Great

51) Sušice – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Su%C5%A1ice

52) Rabí – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Rab%C3%AD_Castle

53) Vimperk – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Vimperk

54) Samo – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Samo

55) Dagobert – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Dagobert_I

56) Franks – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Franks

57) Minnesinger – German lyric poet and singer of the 12th–14th centuries, who performed songs of courtly love.

58) Nibelungen – The term Nibelung is a personal or clan name with several competing and contradictory uses in Germanic heroic legend. It has an unclear etymology, but is often connected to the root nebel, meaning mist.

59) Crécy-en-Ponthieu, Calais. Battle of Crécy – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Battle_of_Cr%C3%A9cy

60) John of Bohemia – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/John_of_Bohemia

61) Black Prince – Edward, Prince of Wales, whose dark armor earned him the name “the Black Prince.”

62) Carinthia is a southern Austrian region in the eastern Alps that encompasses Austria’s highest mountain, Grossglockner.

63) Württemberg is a historical German territory roughly corresponding to the cultural and linguistic region of Swabia. The main town of the region is Stuttgart. Together with Baden and Hohenzollern, two other historical territories, Württemberg now forms the Federal State of Baden-Württemberg.

64) Burgundy is a historical region in east-central France.

65) Provence, a region in southeastern France bordering Italy and the Mediterranean Sea, is known for its diverse landscapes, from the Southern Alps and Camargue plains to rolling vineyards, olive groves, pine forests and lavender fields.

66) Margaret of Tyrol was one of the 14th century’s wealthiest heiresses. As the heiress to the Duchy of Carinthia and County of Tyrol in present-day Austria, she was a very desirable bride. She inherited land caught between three powerful rivalling dynasties: the Habsburgs of Austria, the Luxembourgs of Bohemia, and the Wittelsbachs of Bavaria. Margaret would marry into the latter two. She would spend much of her life making and breaking alliances with these families. However, she would face much slander in her life, which would lead to her going down in history as “the ugly Duchess.”

67) The Maid of Orleans tells the story of Joan of Arc, the 15th-century French heroine who freed the citizens of Orleans, led French troops in glorious victories over the English, and helped Charles VII to be crowned King.

68) Thomas Carlyle book, Frederick the Great.

69) Napoleon Bonaparte, and later known by his regnal name Napoleon I, was a French military and political leader who rose to prominence during the French Revolution and led several successful campaigns during the Revolutionary Wars.

70) Charles I or Karl I was Emperor of Austria, King of Hungary, King of Croatia, King of Bohemia, and the last of the monarchs belonging to the House of Habsburg-Lorraine to rule over Austria-Hungary. During the first part of World War I, he became a skillful military leader without any political influence. The young emperor’s two main aims, the reform of the Austrian Constitution and an acceptable peace, proved to be out of reach. Nevertheless, he consistently refused to resign and died in exile.

Thank you for your support – We appreciate you more than you know!

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Thank you in advance!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.