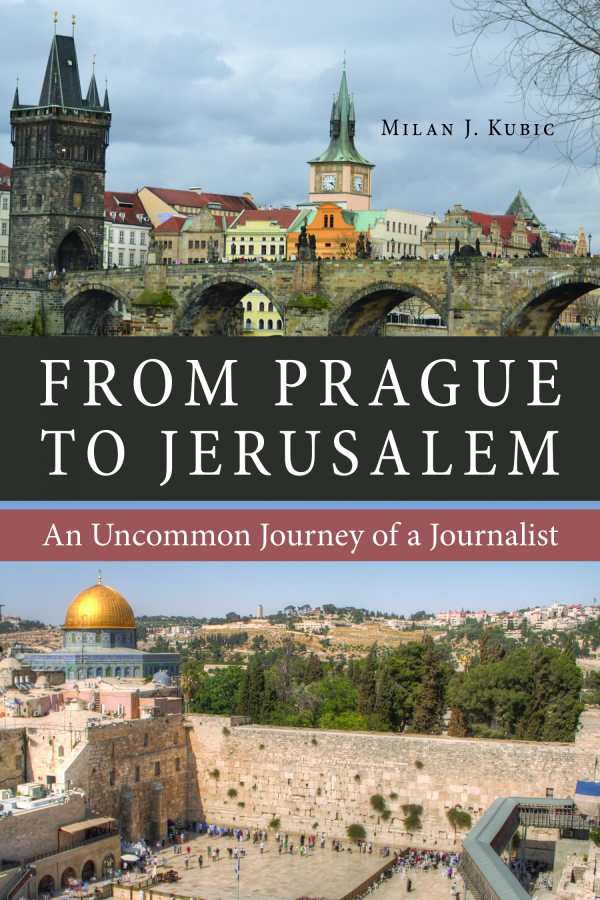

This is an excellent book review of Milan J. Kubic’s book From Prague to Jerusalem. An Uncommon Journey of a Journalist by my friend Miloslav Rechcígl, Jr.

Mila writes:

I have always considered memoir publications important sources of history, particularly after I published my memoir, Czechmate. From Bohemian Paradise to American Haven (2011).

The present autobiographical account of Milan J. Kubic. From Prague Jerusalem. An Uncommon Journey of a Journalist is a splendid example of literature in this category. Interestingly, parts of his story, even age-wise (he is three years older), are not dissimilar from my own odyssey.

Being a journalist, he wrote his memoirs in a highly readable, intimate, and amusing style, although, here and there, he used some uncommon words that forced one to look up their meaning in the dictionary.

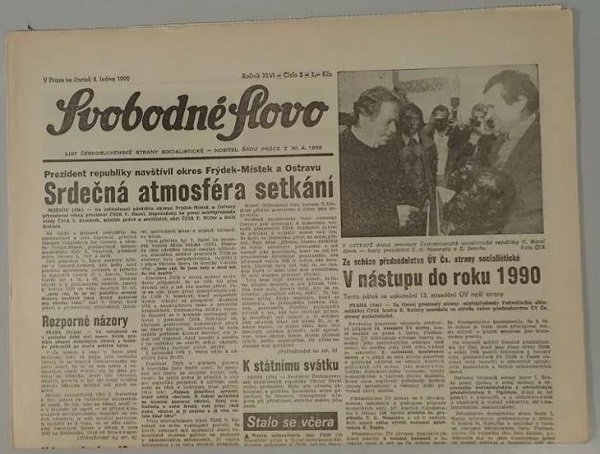

We were both young when we escaped from Czechoslovakia, ending up in the American zone of Germany. However, whereas he was successful on his first try, I was caught at the border and ended up in jail. Nevertheless, I was lucky next year, and after crossing the border, I was moved to a Displaced Persons Camp, which turned out to be in Ludwigsburg, a city in Baden-Württemberg, Germany, about 12 kilometers (7.5 mi) north of Stuttgart, the same camp where Kubic was moved earlier. We then waited there for the US visas to be able to immigrate to the US, although we apparently never met. Interestingly, he got an affidavit from his former boss, the Svobodné Slovo editor, Ivan Herben, with whom I became acquainted in New York and who became my good friend.

We both arrived in the US in the fifties, he in March, while I came one month earlier, where we worked at menial jobs before being able to attend university, get our degrees, and pursue our careers, he as a journalist, while I became a scientist.

Milan J. Kubic is a Medill School of Journalism graduate at Northwestern University who served as a correspondent for Newsweek magazine from 1958 to 1989, covering Washington, South America, Eastern and Western Europe, and the Middle East. Prior to that he worked as a butler and factory worker and served in the US Army intelligence unit during Senator Joe McCarthy’s witch-hunting years.

He was born to a middle-class Prague family, his original name being Kubík. Like myself, he spent his childhood in Nazi-occupied Czechoslovakia, witnessing the Communist takeover of his country in 1948.

He made his journalist debut as a young budding student in the fall of 1945, launching a weekly newspaper Žihadlo (The Sting), which became a hit among his classmates. A barely legible mimeographed paper of a few pages extolled American life’s quality while ridiculing Josef Stalin’s leadership. Unfortunately, the paper was of short duration, having been stopped by the Ministry of Interior. To his consternation, he later found out that it was his own cousin Pepík who betrayed him and reported him to STB (Státní bezpečnost), the State Security, which was firmly under Communist control. Paradoxically, some twenty-five years later, this cousin of his begged him to help him when he decided to also seek refuge abroad.

After completing school, Milan Kubic landed a job as a cub reporter for the Svobodné Slovo, a major liberal Czech newspaper, where he remained until his dismissal following the Communist putsch in February 1948.

This was the reason why he decided to get out of Communist Czechoslovakia.

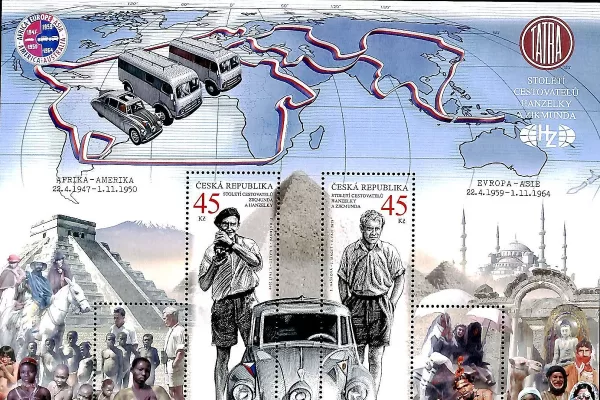

Kubic narrates his life in Czechoslovakia, both under the Nazis and under the Communists, his dramatic escape from Czechoslovakia, and the conditions under which he lived in the German refugee camps. He also describes harsh beginnings and his wife, whom he married before he immigrated to the US. Even though he hardly knew a word of English, he learned it on his own., to such a degree that he was capable of interrogating selected refugees from behind the Iron Curtain and writing detailed reports about what they told him when he worked for the Army intelligence unit during the Korean War.

He was almost thirty when he could return to school and study journalism in earnest. He became an A student by then, leading to his successful journalism career. The latter included stints as a correspondent in Washington, DC (1958-62), bureau chief in Rio de Janeiro (1963-67); bureau chief in Beirut (1967-71): bureau chief in Vienna (1972-73); bureau chief in Bonn (1973-75); and bureau chief in Jerusalem (1976-89).

While in Washington, he covered the White House during the last year of Dwight D. Eisenhower’s Presidency, the US Senate run by Lyndon Johnson and the campaign that elected President John F. Kennedy.

In referring to his stint in South America, he characterized it as “Frustrated in the Hemisphere.” He found the four and half years he spent in this region physically the most demanding and although he worked his heart out, the results were not fully satisfying. He especially disliked and quarreled with the ‘reformadores.’

Not all his South American impressions were negative, however. In November 1965, he joined Bobby Kennedy upon his arrival in Lima, who deeply impressed him. He was telling the Latin Americans to stop their empty posturing and start making real reforms. Kubic also had an interesting encounter in the Brazilian jungle with a tall dignified-looking stranger. When he introduced himself, stating his credentials, the stranger responded in fluent English: “How do you do? I am King Leopold of Belgium.” The retired monarch, an amateur anthropologist, gave him detailed information and guidance about the Brazilian jungle park where they met.

In April 1967, while on assignment in Chile, Kubic was offered as his next beat the Beirut bureau. This was also the time when the Six-Day War started. He then watched the Israeli-Palestinian conflict from Beirut.

Immediately after the Six-Day War, most of the countries on his beat, which included North Africa, Iran, Afghanistan, and Pakistan, closed their borders to US newsmen since they considered them spies. Kubic decided to ignore border regulations and followed the Middle East story wherever it took him. Each time, he had to figure out some ingenious way to outsmart the system, which he described.

Kubic frequently reflected on his conflicting feelings about the Arab-Israeli conflict. Having the reputation of an objective both-sides reporter and not being Jewish opened the door for him to Palestinians because they apparently trusted him and who took him over to show him life in their PLO camps.

While in Beirut, Kubic was intrigued by the happenings in his native country: the Prague Spring and the Czech experiment of liberal “socialism with a human face” under the maverick Communist Party leader Alexander Dubček.

When the Czech borders opened for travelers, Kubic’s brother Mirek unexpectedly arrived in Beirut, who brought him up-to-date on the fate of his family. His father and mother died. After their release from jail, they were assigned the worst and the lowest-paying menial jobs. His cousin Mila was fired from her bank job as a “bourgeois element” and sent to a border region to work as a lumberjack. His brother Mirek was discharged from the army and was sent to dig ditches and mix cement at a construction site. This was part of the regime’s punishment of the whole family for Milan’s escape and his father’s apparent stint in the anticommunist underground.

Then came the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia. The abrupt collapse of the Prague Spring caught thousands of Czechs and Slovaks stranded in Vienna while on vacation, who were now struggling with the agonizing choice between remaining in the West or returning behind the Iron Curtain. Newsweek wanted Kubic to report the story, which eventually led to his new assignment in Vienna.

Although Kubic stayed in Vienna for only one year and a half, this gave him the opportunity to cover Poland, Yugoslavia, and Hungary. He also succeeded in getting a two-week visa to communist Czechoslovakia, after being, initially, turned down by the Czech Embassy in Washington. This visit was not happy because he was constantly tailed there by three two-sleuth teams. Nevertheless, he got the chance to talk to some ordinary people of his generation who had never joined the Communist Party. He even bumped into his brother Mirek in Prague but had steered clear of him for his sake and his own.

Kubic’s assignment to cover East Europe was then enlarged by adding the West European beat while moving from Vienna to Bonn. Moreover, he was also assigned the responsibility of the new Bonn bureau chief.

He found the new environment a mixed blessing. On one hand, West Germany was the opposite of the slothful morass in East Europe: It was a stellar showplace of modern technology and orderly achievement. On the other hand, Kubic still had his memories of World War II: the brutality and humiliation of the Nazi occupation of his native country. Whenever he talked to some elderly German, he always asked himself what that fellow did during the War. At the end of this tour, he played a role in debunking the presumed Hitler diaries, which English language publication rights were offered to Newsweek for sale by Stern magazine.

The last part of the book, which is both autobiographical and historical, concerns Kubic’s last stint in Jerusalem, Israel, from mid-February 1976 till 1989. He found the country fascinating, especially for a reporter. He marveled at the enormous combativeness of Israeli politicians, in contrast to the country’s ethnocentrism, cohesiveness, and the sense of one-family feeling that all the Jews possess. He was greatly impressed by Israel’s success in creating a thriving Western society and nation: a stable democracy, well-functioning institutions, cradle-to-grave welfare, and a modern economy.

Nevertheless, he also saw some negatives, questioning their legendary intelligence services, the government’s genius for press relations, the double-faced occupation policy, etc. He also found faults in several reputed Israeli leaders. Nevertheless, generally, he was delighted by much of what he found in Israel, above all, by the people he dealt with as a journalist.

In many ways, this is a unique publication that offers here-to-fore unknown information. Apart from the glimpses at the author’s life, the monograph focuses on the world personalities Kubic met and the political environment he happened to be in. His unconventional characterization of historical figures who shaped the destiny of mankind throws new light on the memorable events in the 1960-1990 period. His engrossing and riveting monograph, full of intrigue and insight, should appeal to readers and historians interested in world history and politics.

Miloslav Rechcigl, Jr., Rockville, Maryland

Milan J. Kubic was a correspondent for Newsweek magazine from 1958 to 1989, including stints as bureau chief in Beirut, Vienna, West Germany, and Jerusalem. Born in Czechoslovakia, Milan was a refugee and lived in displaced person camps in the U.S. zone in West Germany from June 1948 to February 1950.

From Prague to Jerusalem: An Uncommon Journey of a Journalist is the story of a Czech boy who, after being forced into labor by the occupying Nazis and escaping from the Communists to the United States without speaking a word of English, ends up becoming one of the most prolific American journalists of the second half of the 20th century. Anyone interested in geopolitics or who wonders what life was truly like under the Nazis and Soviets will find it fascinating. It reads like the story of Forrest Gump, with vignettes of traveling the Amazon with Bobby Kennedy (including pictures), having lunch with Dwight Eisenhower, and accidentally meeting King Leopold II of Belgium in the jungle.

Guest Post Author

Mila Rechcígl

Miloslav Rechcígl, Jr. is one of the founders and past Presidents of many years of the Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences (SVU), an international professional organization based in Washington, DC.

He is a native of Mladá Boleslav, Czechoslovakia, who has lived in the US since 1950.

Read his entire profile here.

Discover Mila’s many books on Amazon.

Thank you in advance for your support…

We tirelessly gather and curate valuable information that could take you hours, days, or even months to find elsewhere. Our mission is to simplify your access to the best of our heritage. If you appreciate our efforts, please consider donating to support this site’s operational costs.

See My Exclusive Content and Follow Me on Patreon

You can also send cash, checks, money orders, or support by buying Kytka’s books.

Your contribution sustains us and allows us to continue sharing our rich cultural heritage.

Remember, your donations are our lifeline.

If you haven’t already, subscribe to TresBohemes.com below to receive our newsletter directly in your inbox and never miss out.