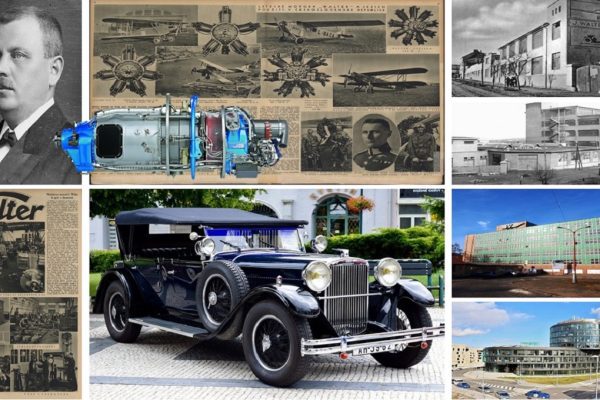

The significant event of October 3, 1953, witnessed the daring border crossing of five determined young men known as the Mašín Gang, equipped with four pistols, as they ventured from Czechoslovakia into East Germany. Driven by a crucial mission, their purpose was to securely convey a classified message from a Czechoslovak general to the U.S. authorities, regardless of the risks involved. Their arduous journey was expected to span three days, leading them towards their ultimate goal of joining the esteemed U.S. Army Special Forces, with the shared vision of liberating their homeland. Little did they know that their audacious act would trigger the initiation of the most extensive manhunt of the Cold War era, capturing the attention and resources of those determined to apprehend them.

Ctirad Mašín

Ctirad Mašín (August 11, 1930 – August 13, 2011) and Josef Mašín (born March 8, 1932) were Czechoslovak brothers who played a significant role in the armed resistance against the communist regime during the years 1951 to 1953. Their actions and the subsequent events surrounding their resistance activities offer a captivating and controversial narrative that sheds light on the complex dynamics of post-World War II Czechoslovakia.

The Mašín brothers were born in Prague and attended high school in Poděbrady following World War II. The rise of the Communist Party to power brought about a transformation of their country’s political landscape, leading to the silencing and persecution of those who opposed the regime. Witnessing the fate of their family’s friends, who were either silenced, vanished, or executed in public show trials, the Mašín brothers developed a strong anti-communist sentiment. Their mother, who had been a friend of Milada Horáková, a well-known victim of judicial murder during the Communist regime, had also experienced the horrors of Nazi concentration camps. The brothers held onto the hope that the United States, having helped establish Czechoslovakia, would eventually intervene and “wipe out Communism.” They drew inspiration from radio stations such as “Radio Free Europe” and “Voice of America,” which seemed to promise an imminent liberation from the communist regime.

Josef Mašín

Motivated by their anti-communist beliefs, the Mašín brothers formed a military resistance group with a small circle of friends. Their uncle, Ctibor Novák, a former Secret Service Officer, joined the group as an advisor. While one source suggests that Novák initially engaged with the group as a means of self-preservation, he eventually became supportive and encouraged the brothers’ actions. The group operated discreetly, with only the brothers and Novák aware of the identities of all members.

The group’s resistance efforts included two raids on police stations in 1951 to obtain weapons and ammunition. Tragically, these raids resulted in the death of two policemen. As their activities became increasingly challenging to carry out, the brothers made the decision to escape to the West, seeking training in partisan warfare from the Americans. They firmly believed that a shooting war against the communist regime was imminent and aimed to return to Czechoslovakia at the forefront of the “liberating” Western armies.

Their first escape attempt failed when a Counter Intelligence Corps (CIC) agent, who was supposed to accompany them, was arrested by the Czechoslovak Secret Service StB. Consequently, the StB arrested Ctirad Mašín, Josef Mašín, and their uncle Novák. The three were subjected to torture, but the StB never discovered their involvement in the police station raids. While Josef and Novák were eventually released after a few months, Ctirad Mašín was sentenced to two years of slave labor for failing to denounce someone else’s planned escape. He endured grueling conditions in a uranium mine near Jáchymov, known for its high mortality rate. Paradoxically, this experience in the Czechoslovak equivalent of the Gulag further solidified his determination to fight against the oppressive regime.

During Ctirad Mašín’s imprisonment, the remaining members of the group attacked a payroll transport and acquired a substantial amount of money. Additionally, they successfully stole four chests containing a total of 100 kg of donarit explosives from a quarry. Their plan was to use these explosives to blow up a uranium train or possibly President Gottwald’s personal train. The final action before their escape was the “Night of Great Fires,” where they strategically placed incendiary devices with time fuses in straw stacks in several Moravian villages. This action served as a protest against the Socialist collectivization of agriculture, intending to not only spread shock and awe but also disrupt the economy of agricultural collectives. Tragically, a firefighter was fatally shot during this operation.

In October 1953, the group made their second attempt to escape to the West, driven by the belief that World War III was imminent as propagated by Radio Free Europe broadcasts. They aimed to participate in the invasion they believed was forthcoming. The group successfully crossed the border to East Germany near Hora Svaté Kateřiny (Deutschkatharinenberg) during the night of October 3rd to 4th. However, their journey to West Berlin was not without challenges. Misunderstanding an announcement on a train, they mistakenly took a train back to their starting point, further complicating their escape. Subsequently, their attempts to hijack a car and another train failed, attracting attention from the police.

Train Station at Luckau Uckro

At Uckro station (now Luckau-Uckro), the police awaited the group and checked passengers. When challenged, the group opened fire, resulting in the death of one policeman and injuries to two others. The group’s actions led to a manhunt, with the pursuit intensifying as their identities became known. The East German police, along with the Kasernierte Volkspolizei (Baracked People’s Police) and even Soviet Red Army troops stationed in the GDR, were involved in the search. Thousands of individuals were involved in hunting down the four anti-communists. Reports of sightings led to numerous gun battles, with casualties among pursuers and innocent bystanders.

The group managed to escape the encirclement at Waldow and continued their journey. Eventually, they reached West Berlin, with Ctirad Mašín hiding under the floor of a suburban train, while Josef and Milan Paumer crossed the border on foot.

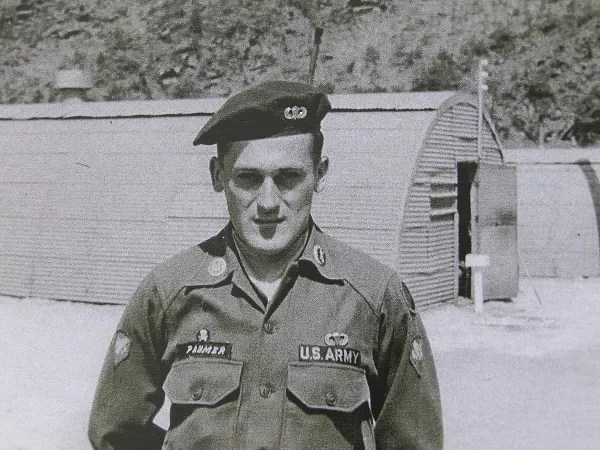

Milan Paumer

Milan Paumer (April 7, 1931 – July 22, 2010) rose to international prominence as a member of the Mašín Gang, a Czechoslovak anticommunist resistance group known for its audacious actions during the early 1950s. Engaging in a series of daring robberies targeting both money and arms, the gang became infamous for their lethal encounters, resulting in the deaths of seven individuals. Their exploits earned them notoriety as they managed to evade the most extensive manhunt ever witnessed in the Eastern Bloc. In October 1953, the group successfully crossed the Czech border into East Germany, navigating their way to West Berlin amidst the relentless pursuit of an estimated 25,000 East German policemen, soldiers, and secret agents. Despite facing intense firefights that claimed the lives of four East German policemen and left two gang members wounded, Paumer and the remaining two members accomplished their objective, reaching the West and eventually finding refuge in the United States.

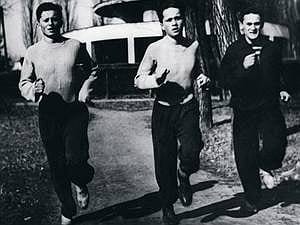

Ctirad “Ray” Mašín

Once in the West, the Mašín brothers enlisted in the United States Army Special Forces at Fort Bragg, North Carolina, serving for five years. Milan Paumer also fought in the Korean War. In the 1960s, Josef Mašín Jr. settled in Cologne, West Germany, while the brothers remained in the United States, refusing to set foot in Czechoslovakia until they were fully rehabilitated. Milan Paumer returned to Poděbrady, Czech Republic, in 2010 and passed away the same year. Ctirad Mašín died in Cleveland, Ohio, in 2011.

The repercussions of the Mašín brothers’ resistance activities were significant. In Czechoslovakia, individuals associated with them faced severe punishment, with executions, imprisonment, and mistreatment of family and friends. The communist propaganda machine exploited the Mašín’s actions, portraying them as looters and brutal murderers. These events were used to justify strict control over society and the ruthless treatment of any opposition.

Josef “Joe” Mašín

In 2005, the Czech and Slovak Association of Canada honored the Mašín Brothers and Milan Paumer with the prestigious Thomas Masaryk Award, acknowledging their remarkable contributions. Later, on February 28, 2008, Czech Prime Minister Mirek Topolánek presented the Mašíns with the newly established “Prime Minister’s Medal” at a ceremony held at the Czech Embassy in Washington. Subsequently, on March 4, 2008, another ceremony took place in the Czech Republic, where Milan Paumer was also decorated.

It is worth noting that the Prime Minister’s Medal is a personal decoration, not one bestowed by the Czech state. Prime Minister Topolánek’s intention was to initiate a dialogue on the concept of the “third resistance,” which refers to the anti-Communist struggle, controversially categorized alongside the first and second resistances against the Austro-Hungarian Empire (1914-1918) and Nazi occupation (1939-1945), respectively. By initiating such discussions, Prime Minister Topolánek hoped to pave the way for the Mašíns’ eventual official state recognition.

In the wake of the Communist regime’s downfall, Milan Paumer returned to his native Czech Republic and settled in his hometown. However, his presence remained a subject of controversy, with some condemning him as a murderer while others lauded him as a heroic figure of resistance. In recognition of his actions, the Czech government honored Paumer in 2008, and Prime Minister Petr Nečas praised his courageous decision to combat Communist oppression. The complex legacy of Milan Paumer continues to spark debate and reflection, highlighting the nuanced perspectives surrounding his involvement in the struggle against authoritarian rule.

The question of whether the five fighters of the Mašín Gang are to be regarded as villains or heroes remains a subject of contention. Critics argue that their actions, such as Ctirad’s slitting of a policeman’s throat while he was incapacitated, and the group’s killing of six individuals, including a wages clerk, paint them as villains. Detractors of the gang contend that their objectives were pursued through irresponsible and inappropriate means, inflicting more harm than good and exhibiting excessive violence. Furthermore, their engagement in criminal activities such as robbery further tarnishes their image. During the era of totalitarianism, the group was consistently portrayed as villains, with even the popular television series “Major Zeman” depicting their capture by the fictional Communist policeman.

However, there are those who lend their support to the Mašín Gang, asserting that Nazism and Communism shared a similar absence of the values and principles necessary for a democratic and moral society. From this perspective, the group’s acts of eliminating Communist policemen and those responsible for safeguarding state and Communist funds are seen as justified. Advocates for the Mašíns argue that they were engaged in a struggle against a horrific regime and should be recognized as heroes. Regardless of these differing viewpoints, there is unanimous agreement on one aspect: the extraordinary courage displayed by the five fighters.

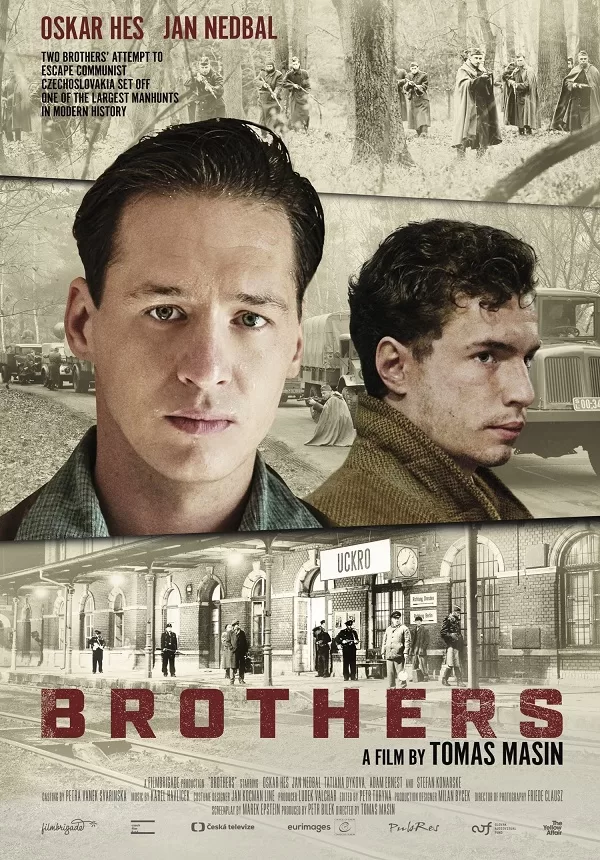

Click to learn more about the film here.

Numerous books, documentaries, and fictional adaptations have been created to recount the story of the Mašín brothers. However, perspectives on their actions remain deeply divided. They are revered by some as heroes who defied an oppressive regime, while others condemn their methods, particularly the acts of violence that claimed innocent lives.

The controversy surrounding the Mašín brothers continues to spark debates and divide public opinion in the Czech Republic. Efforts to gain official state recognition for their resistance struggle persist, as politicians grapple with the challenge of reconciling the brothers’ actions with the complex history of Czechoslovakia’s post-war era.

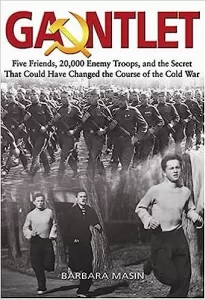

Recommended book: Gauntlet: Five Friends, 20,000 Enemy Troops, and the Secret That Could Have Changed the Course of the Cold War.

The Institute for the Study of Totalitarian Regimes received an open letter from Josef Mašín, Ctirad Mašín and Milan Paumer, in which they express themselves regarding the event from the beginning of the 1950’s of the last century that has been hitherto inaccurately reported in the media, concretely, information about one of the planned actions of their resistance group – the assassination of the chairman of the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia and the President of the Czechoslovak Republic, Klement Gottwald.

Regarding the Czech film, you can view the trailer:

* * * * *

Thank you in advance for your support…

You could spend hours, days, weeks, and months finding some of this information. On this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

We appreciate you more than you know!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.