Imagine if we could travel back in time to Prague. Would you like to go back 100 years with me? The following is a chapter from a book published in 1912, entitled Around the Clock in Europe: A Travel-Sequence by Charles Fish Howell with illustrations by Harold Field Kellogg. Published in Boston by Houghton Mifflin Co., this is an account of Prague from over one hundred years ago. As you read, you may see that some of the spelling is off, but I have tried my best to add current spelling or information to the piece for your understanding. Again, this was written over 100 years ago – I am posting it here in the spirit that we travel back in time to Prague during the early 20th Century. Let’s go!

My notes and additions appear in (parentheses) as shown.

The author has endeavored to catch and present faithful impressions of the streets, their kaleidoscopic animation, and the activities and characteristics of the people; to touch the pen-pictures with a light overwash of the racial and national peculiarities that distinguish each, and to invest them with what insight, sympathy, and enthusiasm he is capable of. It is “fitting the scene with the apposite phrase,” as Mr. Howells has so aptly described the process and as he himself has so wonderfully exemplified it. A formidable undertaking? Indeed, yes; but there is the dictum of Mr. Browning that the purpose swells the account.

These, then, are impressionistic sketches. They are of the moment only. It has been sought, most of all, to give them just that character. They have been written as reflecting the probable observations and emotions of visitors of normal enthusiasm during these hours and in these environs. Under such conditions, it is well to remember, every active mind has its sudden, drifting excursions afield; something in the visible, present surroundings whimsically invokes the subtle genii of Memory and Imagination, and one is whisked off in a breath, and without rhyme or reason, to the most ultimate and alluring Isles of Thought. These swift and scarcely accountable flights are the common experience of all travelers, and the author has felt it to be a part of his task to take proper cognizance of them…

Sweet the memory is to me, of a land beyond the sea.

~Longfellow

~ ~ ~

A brooding, stolid city is Prague; the somber capital of a restless, feverish people. It is the hotbed and “darling seat” of all Bohemia; and Bohemia languishes for her lost independence as Israel did by the waters of Babylon. She does not, however, pine in hopeless despair like the Hebrews, but nourishes a keen expectation of regaining her lost estate, and grits her teeth, in the mean while, with fiery impatience. She points, and with reason, to the fact that the Slavs — Czechs, Slovaks, and Moravians — easily outnumber the Hungarians; yet Hungary is free, and she in bondage. And so Bohemia, for all her exterior of gracious courtesy, is bitter and hard at heart; a people of a passionate, thwarted patriotism; a people that has suffered and been degraded, but that has never for a moment forgotten. Prague is an expression of all this; in her sullen, gloomy architecture; in the persistence of national types and characteristics; and peculiarly in the wild, reckless Moldau*, which visualizes the traditional, savage intolerance that is bred in the bone of the fatalistic Slav.

(*The Vltava River. German: Moldau, is the longest river within the Czech Republic, running southeast along the Bohemian Forest and then north across Bohemia, through Český Krumlov, České Budějovice and Prague, and finally merging with the Elbe at Mělník. It is commonly referred to as the “Czech national river”. Both the Czech name Vltava and the German name Moldau are believed to originate from the old Germanic words *wilt ahwa (“wild water”; compare Latin aqua). In the Annales Fuldenses (872 AD) it is called Fuldaha; from 1113 AD it is attested as Wultha. In the Chronica Boemorum (1125 AD) it is attested for the first time in its Bohemian form, Wlitaua. Source.)

There are too many daws about for Prague to wear her heart on her sleeve, so while she bides her time she presents a smiling mask. It may sometimes be a rather weary smile, and the forests that engulf her are gloomy and sinister; but her skies are not always lowering and overcast, and the peace of her fatigue from the national struggle is profound. It is just this deep, brooding peace that appeals to the stranger within her gates; and along with it he senses here a wonderful charm and underlying subtlety that invests this curious old city with a lambent play of the imagination.

It was of Prague that Alexander von Humboldt said: “It is the most beautiful inland city I have ever seen.” And it must have been of some such spot that “R. L. S.” was mindful when he expressed the paradox that “any place is good enough to live a life in, while it is only in a few, and those highly favored, that we can pass a few hours agreeably.” Restfulness is surely one of the prime essentials of the “highly favored” few; and there is no restfulness at all comparable with that we feel in some venerated spot whose present hush and quiet is a reaction from its other days of fever and turmoil. One finds these qualities in Prague, whose calm and serenity seem doubly intense in contrast with its history of tumult and savagery and the hatred and violence that racked and convulsed it for hundreds of years. It has frequently been lightly disposed of as being an “out-of-the-way place”; but no place is more delightful than an “out-of-the-way” place, and particularly when it has the natural and architectural beauty of this one, or has been the theatre of such unusual and stirring occurrences.

Had we but one hour to spend in Prague we should certainly choose the charmed one between four and five o’clock of an afternoon. The sunshine is then most languid and golden, and the day declines slowly over the castled tops of the Hradschin-crowned slope, and the lengthening shadows of towers and turrets creep out on the river, and the copper domes and ruddy tiles of the Neustadt glow in bright spots against the darkling green of the wooded hillsides. If one does not then feel a profound and elevating sense of tranquillity and translating beauty, it will be because he has eyes to see yet sees not.

Since Prague rests under the imputation of being “out of the way,” — and even Shakespeare set this inland kingdom down as “a desert country near the sea,*” and lost his compass completely in the shipwreck in the “Winter’s Tale” with Antigonus exclaiming: “Our ship hath touch’d upon the deserts of Bohemia”; and a confused mariner replying, “Aye, my lord; and fear we’ve landed in ill time,” — we may, perhaps, be pardoned for observing that in general appearance it is a wooded valley traversed in its full length by a swift, turbulent river, which follows a northerly course excepting where it bends sharply to the east in the very heart of the city. This stream, the Moldau, rushes along as if in desperate haste to throw itself into the Elbe, and seems to have the one idea, as it dashes through Prague, of getting done with its business and on its way at the earliest moment possible. It has scoured its islands into ovals, slashed the rocky bases of the hills, and continually assailed its bridges and quays. But through all its exhibitions of ill humor the Praguers have indulgently condoned and even extolled it; it was only when the beloved and venerated Karlsbriicke fell a partial victim to its violence, a dozen years ago, that patience ceased to be a virtue and the unnatural marauder was comprehensively anathematized with all the sibilant fury of the hissing tongue of the Czech. Speed apart, there is little to complain of with the Moldau; it is broad and of a pleasant deep blue, and the beauty it supplies to the setting of the city is supplemented by the importance of its traffic, the amusements on its many little wooded islands, and the delights of its boating and bathing. In a word, it is a noble stream — and none the less Bohemian, perhaps, for being a little proud and headstrong.

(*Note: In A Winter’s Tale, Shakespeare gives the description of ‘Bohemia. A desert country by the sea.’ as the header to Scene III in Act III of the play. The scene’s opening line from Antigonus to a mariner goes ‘Thou art perfect then, our ship hath touch’d upon / The deserts of Bohemia?’ relaying that perception to the audience. The play was performed for King James at court in 1611. The region of Bohemia (in Czech called Čechy) makes up the western two thirds of the Czech Republic, the remainder being made up by Moravia and Czech Silesia. It’s political, historical, and cultural center is the city of Prague. A picture-map from 1570 shows Bohemia not only at the heart of Europe but as its heart. Source.)

As the afternoon sun lies heavy over Prague one notes with delight how snugly the old city nestles along the river and up the hillsides of the valley, and with what a natural and comfortable air; not at all as though trying, as newer cities do, to shoulder its suburbs out of the way. It seems a perfect type of the mediaeval town, with buildings of solid stone of an agreeable and universal creamy tone, four-square and enduring. It abounds in quaint, high pitched roofs; incurious, turreted spires; in red tiles and green copper domes; and in objects of antique and archaic fascination. Shade trees are everywhere. Indeed, from the thickly wooded heights of the surrounding hills right down to the river quays the gray of the houses and the red and green of the roofs make beautiful color combinations with the feathery foliage.

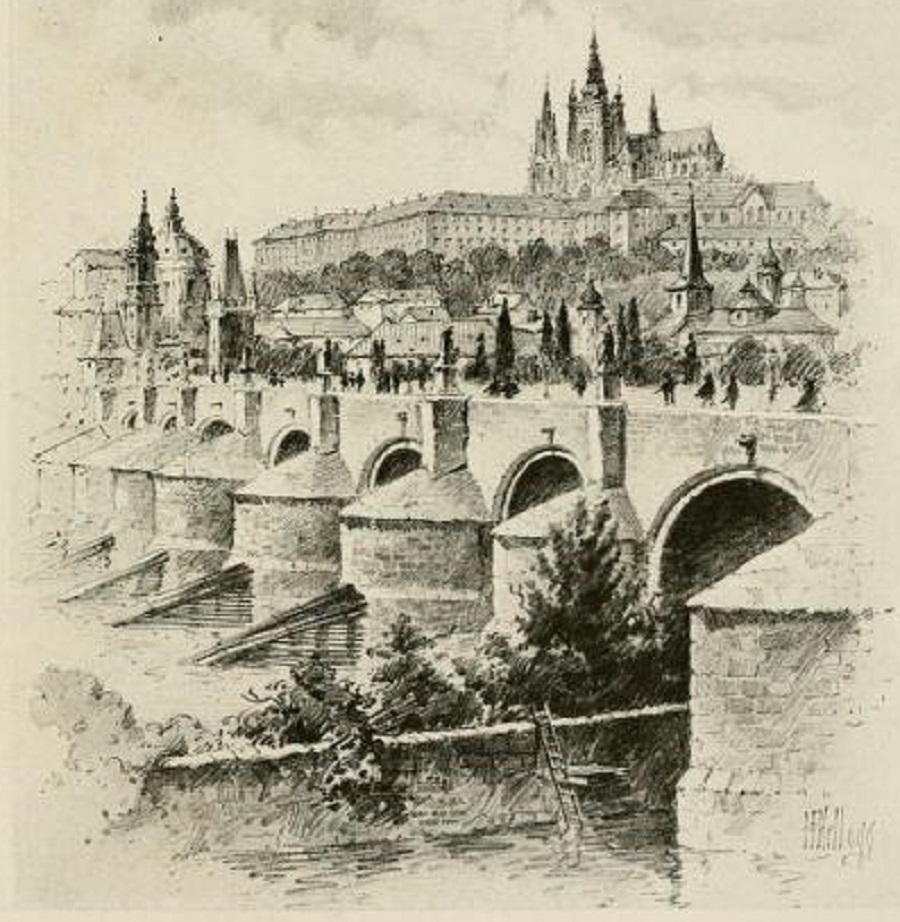

One stands on the old Karlsbrucke (Charles Bridge) and looks upstream and there he sees the rocky heights of the Wyschehrad (Vyšehrad) Hill on which the fair and wise Libussa (Libuše is a legendary ancestor of the Přemyslid dynasty and the Czech people as a whole.) reared her castle when she laid the foundations of the city, thirteen centuries ago, and which he will want to visit later to look over the fortifications and to study the glowing frescoes on the cloister walls of the Benedictine monastery of Emmaus. In the elbow of the Moldau, downstream, he will observe the old sections of Prague huddled together in cramped confusion, with no sign left of the ancient separating walls that once defined the original seven districts, though he is to learn, by and by, that the early names remain unchanged — the Aldstadt (Old Town, or Staré Mesto), and the Jewish Josephstadt (Called Josefov, or the former Jewish ghetto), and around and above them the Neustadt (New Town or Nové Město), which, of course, from an American time-point, is really not “new” at all. On his left, along the river, he sees the Kleinseite (Malá Strana, also known as Lesser Town) spread out, and on the hillside above it that far-famed acropolis, the redoubtable Hradschin (Hradčany), with its dusty, barracks-like royal and state palaces, and the great bulk of the cathedral of St. Vitus rising out of it like some man-made mount. Such is the first bird’s-eye impression of Prague, set in its wooded slopes, stolid and softly colored. Later on one can scrape acquaintance with its rambling, flourishing, modern suburbs, to the eastward and downstream, and wrestle at his pleasure with such impressive nomenclature as Karolinenthal (Karlín) and Bubna-Holeschowitz (Holešovice, or Holešovice-Bubny).

Between four and five o’clock the visitor will find an especial pleasure in noting the activities that prevail in the several little green islands that fret the impetuous Moldau as it hurries through this “hundred-towered, golden Prague.” The dearest of these to the sentimental Czech is bright Sophien-Insel (Sophia’s Island, Slovanský ostrov or Žofín), that you could almost leap onto from the stone coping of the neighboring Kaiser-Franzbriicke.

It always wears a gay and inviting appearance, with café tables set under fine old oaks, but precisely at four, summer afternoons, the leader of its military band lifts his baton and launches some crashing prelude, and the noisy company instantly stills and with nervously tapping fingers and glowing eyes abandons itself to that music passion which is the deepest and most intense expression of the Bohemian temperament. It gives the dilettante a new conception of the power of this inspiring art to observe the significant and varying expressions that play over the faces of a Prague audience under its influence. He witnesses then the profoundest stirring of the Slavic nature and the moving of emotional depths beyond the conception of the reserved and impassive Anglo-Saxon. Especially is this so when the music is of a national character, such as the “Ma Vlast*” symphonic poems of Smetana, or a Slavic dance of Dvorak’s.

(*Note: Má vlast, also known as My Fatherland, is a set of six symphonic poems composed between 1874 and 1879 by the Czech composer Bedřich Smetana. The six pieces, conceived as individual works, are often presented and recorded as a single work in six movements. They premiered separately between 1875 and 1880. You can listen to the pieces by clicking here. – It plays nicely in the background while you finish reading.)

These Bohemian masters, with their fellow countryman, Zdeněk Fibich, constitute a trinity that is reverenced in their native land to an extent that almost passes belief, and that has done so much in making Prague one of the foremost centers of Europe. The music from the Sophien-Insel floats down the river to our vantage-point on Karlsbrucke, mellowed and softened, and contributes just the right pleasing note to the agreeable mood these picturesque surroundings excite. The ponderous, antique old structure on which we stand has the appearance of some full-page color illustration for a charming Middle-Age romance.

For half a millennium it has dug its broad arches into the bottom of the Moldau, stoutly defiant of flood or storm. Its massive buttresses are crowned with heroic statues so deeply revered that pilgrimages are made by the faithful to pay their devotions before them. For a third of a mile this old veteran strides the stream, and at each end he lifts an amazing mediaeval tower well worth a journey to stare at. These ponderous structures, weathered by centuries of storm to a rich brownish black, are pierced by a deep Gothic archway through which the street traffic pours all day. Their sides are decorated with colonnades and traceries, armorial bearings and statues of ancient heroes of the city, and their tops are incredible creations of slender turrets and of pointed roofs so desperately precipitate that they seem like long narrow paving-stones tilted end to end.

Catholic legend and ceremonial run riot on the old bridge. The statues are almost altogether of a religious character, and two of them, the Crucifixion Group and the bronze one of St. John Nepomuc* are practically never passed without the sign of the cross and the raising of hat or cap; in the case of the latter the devout will touch the tablet that marks the spot from which he is said to have been cast into the river, and then kiss their fingers and bless themselves. For St. John Nepomuc, of all the holy martyrs, was Prague’s very own.

(*Note: Svatý Jan Nepomucký – Read about Czechs and their Religious beliefs.)

The legend is dramatic. Father John was the queen’s confessor, five hundred years ago, and when he declined to oblige the king by revealing what the queen had told under the seal of the confessional, his Majesty had him summarily cast into the Moldau, from just where we are standing at the centre of this bridge. The result was far from the expectations of the king, for not only was the poor priest preserved from sinking, but — which is quite as hard to believe of so swift a stream as this — he actually remained floating for four days at the very spot where he fell, and five bright stars hung above him all the while! When they took him out he was dead, and to this extent only did the king succeed. As was perfectly natural, the amazed Praguers could see nothing in all this but an astounding miracle; and when Catholicism had finally displaced the Protestantism that followed the Hussite wars for two hundred years, their clamor for the canonization of Father John eventually resulted in placing the name of St. John Nepomuc in the catalogue of Rome. Equipped with a saint all their own, they adroitly converted the statues of the Protestant John Hus*, that stood here and there about town, into St. John Nepomucs by the simple expedient of adding a five-starred halo to each.

(*Note: John Hus – A Brief Video Overview of the Man.)

Now, if today were the sixteenth of May, St. John Nepomuc’s special day, we should behold the greatest festival of all the year. An altar would be erected beside his statue, here on the bridge, and mass celebrated before enormous kneeling crowds. Bohemian peasants would flock into town from miles and miles around, in all the picturesque finery of the national dress, gala performances would be given at the theatres, an especial illumination of the city made at public expense, and fireworks displayed tonight on Schutzen-Insel (Střelecký Island or Střelecký ostrov). It would be an orderly celebration, too, for the Czechs are more fond of dancing than drinking; and religious enthusiasm would be practically universal, for Prague, which for two centuries was exclusively Protestant, now numbers at least nine Catholics out of every ten of its people*

(*Note, written in 1910. Obviously these statistics are outdated.)

As we look about us this afternoon we derive a vivid consciousness of being very far from home, set down in an environment that is, for Europe, oddly foreign and unfamiliar. The soft, sibilant prattle of the Czechish speech is heard on every hand, and the names on cars and corners are outlandish to us, with their profusion of consonants and curious accent marks like our o and v. One sees a great disproportion in numbers between the German and Czechish population; only thirteen to the hundred are said to be German, but in the opinion of Bohemians that is too many, for the stubborn struggle for the existence of the old national speech and spirit against the threatening usurpation of the eutonic invaders is a real matter of life and death.

As we watch the crowds throng along the bridge the prevalence of the Slavic type is very noticeable: short of body, heavy of head, and with high cheek bones and coarse features. The general expression is one of settled melancholy, bred of their peculiar fatalism. Having heard the “Bohemian Girl*” and read the foundationless libels of popular French literature, one looks about for gypsies; he will be lucky if he finds one. Bohemia, as he should have known, is one of the leading industrial countries of Europe, and Prague is made up of hard-working, skillful mechanics. Energy and resolution are stamped on these serious, rugged faces; on the powerful men, the tall, strong women, and even on the little black-eyed children. And they can do many worthy things well: they market the country’s rich coal and iron deposits, make garnets to perfection, and manufacture beet-sugar by thousands of tons.

(*Note: The Bohemian Girl is an Irish Romantic opera from 1843, composed by Michael William Balfe with a libretto by Alfred Bunn. The plot is loosely based on a Miguel de Cervantes’ tale, La Gitanilla.)

Who has not heard of Bohemian glass, or Pilsener beer? And shall we belittle the resourcefulness of Bohemia, with the prosperous resorts of Karlsbad (Karlovy Vary) and Marienbad (Mariánské Lázně) well within the western boundary of the Bohmer Wald*? If this does not convince, one has only to run over to Dresden, seventy-five miles away, which he can reach by rail in four hours at an outlay of but eight florins, and ask any one where the finest farm produce comes from and what section yields the best fruit and honey, butter and eggs, milk and cheese.

(*Note: The Bohemian Forest, known in Czech as Šumava and in German as Böhmerwald, is a low mountain range in Central Europe. You may like to read our article, The Ancient Bohemian Forest Known as Šumava.)

If now we can manage to look away from the bridge and its crowds, we shall observe that the afternoon activities of the river-life of Prague are manifold and highly interesting. There is a prodigious bustling about of longshoremen on the fine, broad quays, and boats of many descriptions and diversified cargoes are laboriously struggling upstream or drifting guardedly down. From time to time huge, unwieldy rafts pass along to the din of vigorous shouting and hysterical warnings. Bathers at the riverside establishments are adding their share of laughter and frolic, their diversions watched with vast amusement by the afternoon idlers loitering along the embankments. On our right the shaded walks and trim lawns of the popular Rudolf s-Quai (Anyone???) are comfortably filled with a leisurely company of promenaders and of nursemaids airing their charges.

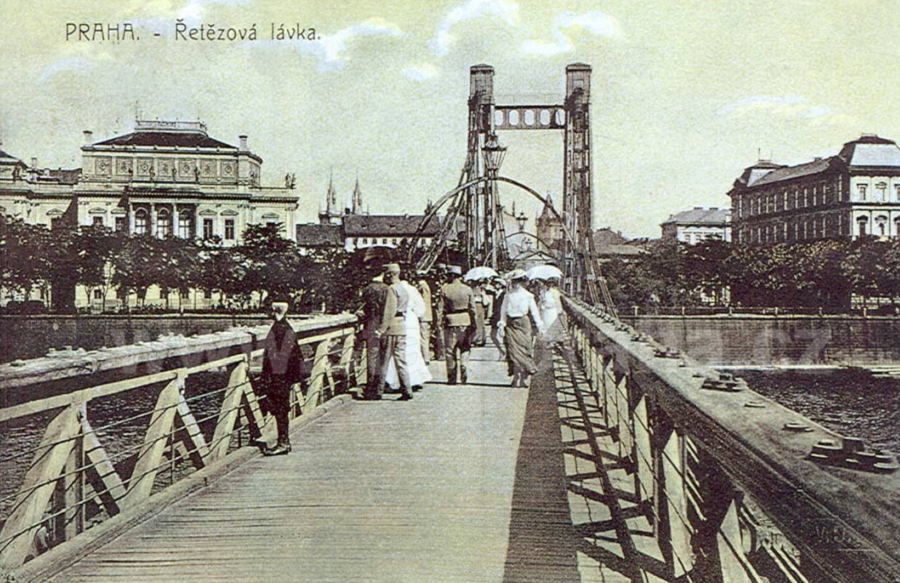

All this contributes an agreeable note of homeliness and contentment and seems eminently in harmony with the prevailing serenity and peace of the surrounding groves. There is at hand a little chain footbridge which they call the Kettensteg*, and in a beautiful clump of lindens at its end rise the sculptured porticoes of the classic Rudolfinum, Prague’s noble home of the arts and industries. Enter it, and you find whole halls devoted to the work of Bohemian artists, with the school of old Theodoric of Prague represented in surprising completeness, an entire cabinet filled with the engravings of that famous Praguer, Wenzel Hollar, and many of the most beautiful paintings of such celebrated Bohemians as Gabriel Von Max, Vaclav Brozik and Josef Manes.

(*Note: The Rudolfova lávka also Železna lávka, German mostly Kettensteg was a chain and pedestrian bridge over the Vltava in Prague. It was the predecessor of today’s Mánes Bridge (Mánesův most) and was located north, downstream from it. The structure was built from 1868 to1869 and was the third suspension bridge in the capital of Bohemia.)

With artistic bridges arching the river in whichever direction you look, with music and soft voices welling up from the gay islands, and with a full and virile life at cry along the quays, you find yourself about as far removed as possible from the atmosphere of Longfellow’s “Beleaguered City“

Beside the Moldau’s rushing stream, With the wan moon overhead, There stood, as in an awful dream, The army of the Dead.

~Longfellow, Beleaguered City

Assuredly, there is no “army of the dead” at this hour beside the Moldau, whatever there may be under the “wan moon” in a poet’s eye. On the contrary, there is an army of the living, a quarter-million of them, and it marches without resting, day in and day out, along the Graben* and the stately Wenzels-Platz (Wenceslas Square or Václavské náměstí), and through the venerable Grosser Ring (Old Town Square or Staroměstské náměstí) and the narrow, crooked alleys of old Josephstadt.

(*Note: Na příkopě, informally also Na Příkopě, Na Příkopech or Příkopy, is a street in the center of Prague, Czech Republic, connecting Wenceslas Square with the Republic Square. Na Příkopě street leads on the site of former 10-meter-wide and 8-meter-deep moat from 1234, which led along the medieval walls of the Old Town. Water flowed directly from the Vltava river and when the moat was filled, the Old Town formed a closed island. The moat was covered in 1760. After covering, chestnut trees were planted here and the street was named Ve starých alejích (In old alleys). In 1845-70 the street was named Kolowratská třída and since 1871 bears the name Na Příkopě. Because it was one of the few very wide streets in Prague, it soon became a traffic artery. Since 1875, the first line of the Prague horse-drawn tram has been lead here, which has been electrified since 1899. In 1919, Můstek became the first intersection in Prague to be controlled by a traffic policeman. In 1927, then the second intersection with the light signaling – the first being Hybernská-Dlážděná-Havlíčkova intersection.)

Walk east across Karlsbrucke, pass under the Gothic arch of the somnolent Aldstadt Tower (Old Town Bridge Tower or Staroměstská mostecká věž), with the stony statue of Karl IV on your left, and you will shortly emerge on the Grosser Ring and can settle the matter for yourself. This fantastic Ring is the oldest and most famous square of the city, still preserving its ancient appearance. You find it an irregular quadrilateral, surrounded by quaint, gloomy, colonnaded houses, churches, and dilapidated palaces. There towers in its center a somber memorial column, called the Mariensaule*, commemorating Prague’s liberation from the Swedes at the close of the Thirty Years’ War. The very first thing to catch the eye is the singular Teynkirche (Kostel Matky Boží před Týnem, Týnský chrám or Church of Our Lady before Týn) — the old Gothic church where John Hus so often preached, where the astronomer Tycho Brahe lies entombed in red marble, and in whose shadows, through five centuries, many of the bloodiest events of the city had their inception and execution. The influence of Hus on the Europe of his day was so great and has continued so long that it is hard to realize that he had only reached his forty-sixth year when the Council of Constance sent him and his friend, Jerome of Prague, to the stake.

(*Note: Mariánský sloup or Marian column of Prague is a religious monument consisting of a column topped with a statue of the Virgin Mary, located in the city’s Old Town Square. The column was erected in 1650, shortly after the conclusion of the Thirty Years’ War. It was demolished in November 1918, coinciding with the fall of Austria-Hungary.[1] In 2020, the column was reconstructed, with planned completion on 15 August 2020.)

The old Teynkirche, where he so often attacked the doctrines of Rome, still rears its battered and darkened bulk from behind a melancholy row of colonnaded houses and gazes solemnly and patiently over them at the noisy Ring, its lofty spires curiously clustered with airy turrets like hornets’ nests on some old tree. Directly opposite, the modern Gothic Rathaus (Town Hall) shoulders up to the moldering tower of its predecessor whose famous clock (Prague Astronomical Clock, Prague Orloj or Pražský orloj) has delighted its thousands with the surprising things the automatic figures do when the hours and quarters roll around. Just at hand, a portion of the old Erkerkapelle (Archbishop’s Chapel – the old windows part of the old towne hall) still stands in excellent preservation, and you could not find more beautiful Gothic windows in all Prague, nor finer canopied saints nor more richly sculptured coats of arms. Before this building — a place of hideous history — the best blood of the city was spilled after the fall of Bohemian independence at the fateful battle of the White Hill, three centuries ago, when twenty-seven nobles were butchered here on the scaffold.

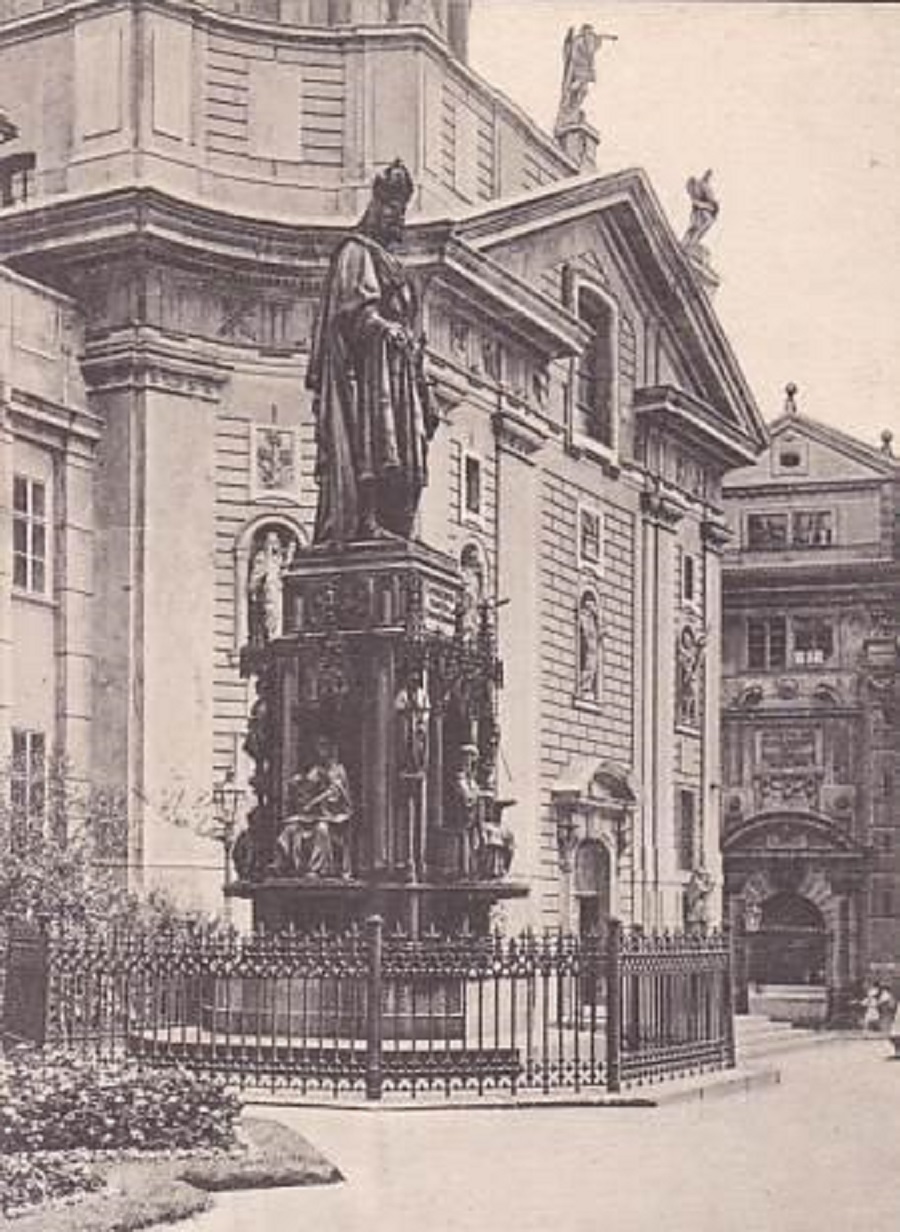

A dozen years passed, and again blood soaked this earth, with the stony-hearted Wallenstein executing eleven of his chief officers for alleged cowardice at the battle of Lutzen. Prague still shows the palace of Wallenstein, and those of the other two famous generals of his period, Gallas and Piccolomini. The Clam-Gallas Palace is just at hand, in the Hussgasse (Jan Hus Memorial), distinguished for its beautiful portal flanked with colossal caryatids and sculptured urns, and surmounted by a marble balustrade wrought with the perfection of life. A final note in the Old-World charm of the Grosser Ring is contributed by the ancient Kinsky Palace (Kinský Palace or Palác Kinských is now National Gallery Prague) is a former palace, now an art museum, adjoining the Teynkirche, in the elaborate baroque architecture despised of Mr. Ruskin. People in the manner and seeming of today walk and talk, barter and sell under the nodding brows of these historic buildings, but the visitor stands among them unconscious of their noisy presence in the spell such storied surroundings cast on every phase of fancy and imagination.

There is a peculiar fascination about aimless rambles in Prague. Modern improvements have come, of course, but many an old and rare landmark has been reverently preserved, with the result that you can scarcely turn a corner or cross a square without coming face to face with some fantastic and blackened architectural fragment that holds you spellbound with wonder and delight. Whole sections, indeed, are of such a character; as you would find were you to fare forth from the Grosser Ring and seek adventures by crossing the Kettensteg and invading the region beyond the Rudolfinum.

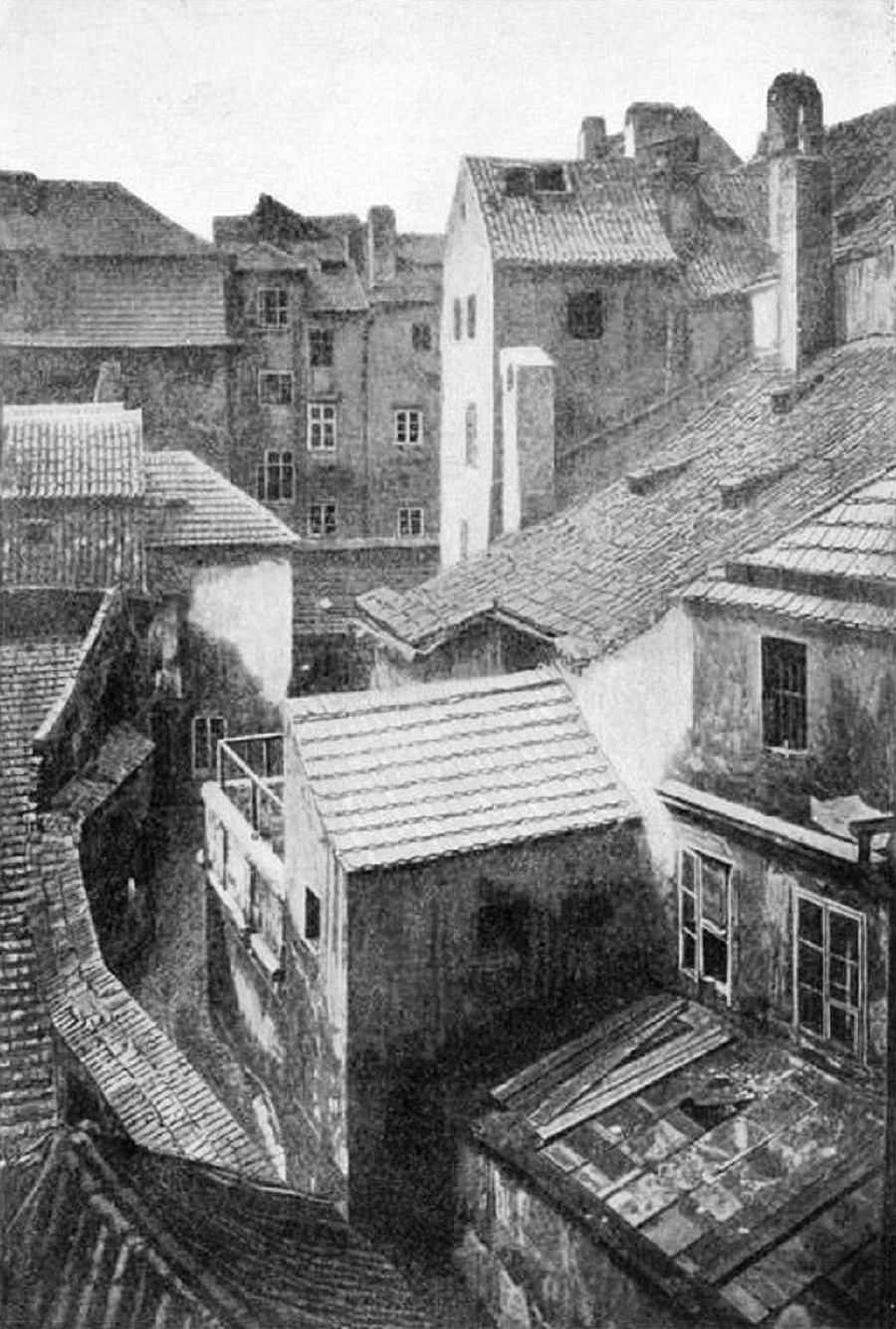

With almost the suddenness of tumbling into a river you would find yourself groping, even at this bright hour of the afternoon, in the black and twisting mazes of the old Jewish Ghetto that still goes by the name of Josephstadt. Here you have at once all the detail and color of a romance of the crusades. Everything appears aged and eccentric. The time-weary, saddened, ramshackle houses project their upper stories feebly and seek to rest their wrinkled foreheads on one another; tortuous, winding alleys that you can almost span with your outstretched arms reel giddily all ways from a straight line, plodding wearily uphill and sliding helplessly down. On all sides there seems to be a general feeling that nothing matters, that everything comes by accident or caprice.

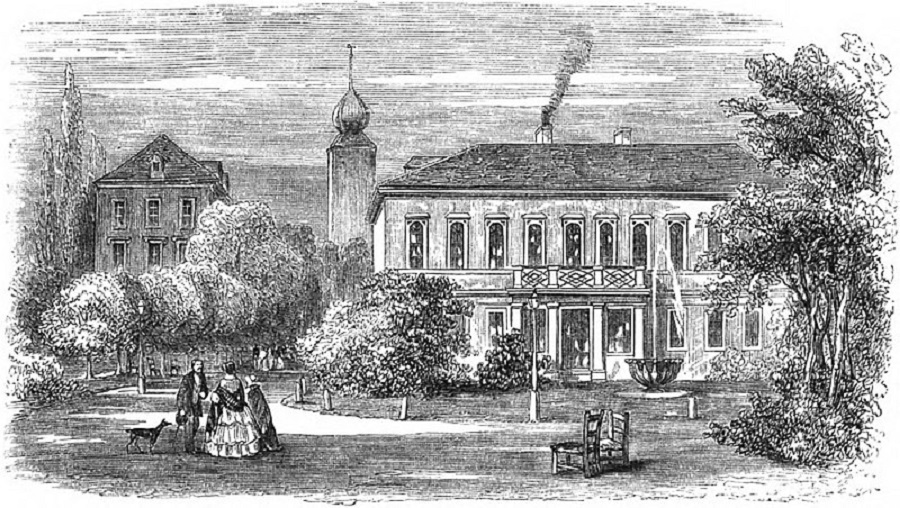

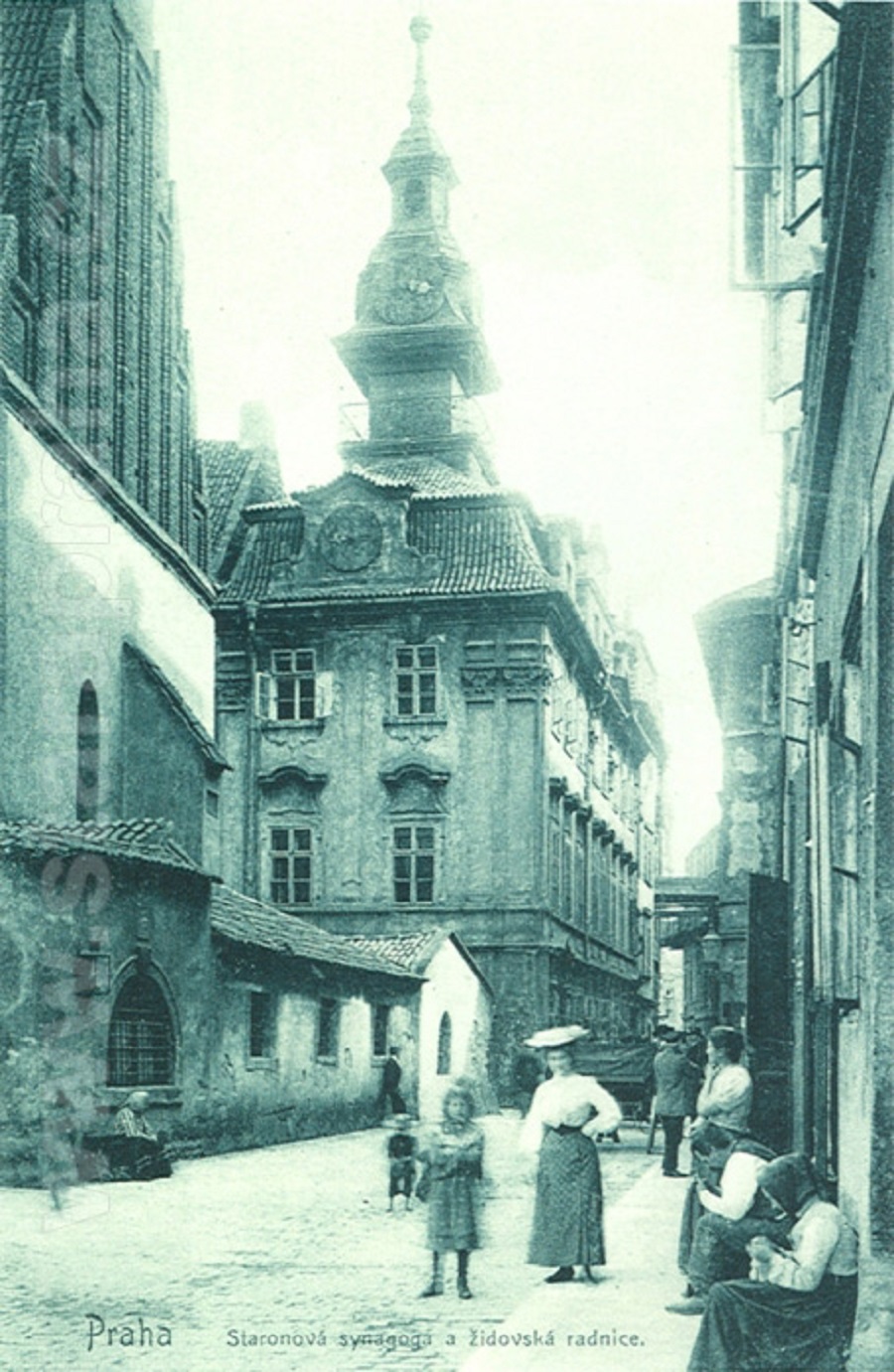

Over the frowzy heads of slovenly children quarreling in the doorways, glimpses are to be had of dark and filthy interiors, from which foul odors escape to the street. Long-coated, unkempt patriarchs of Israel lope solemnly by, with rounded shoulders and hands clasped behind; and if you follow in their wake you will sooner or later arrive at a curious, melancholy Rathaus (The Jewish Town Hall or Židovská radnice) that is a rare jumble of architectural orders and has an extraordinary steeple that might once have done time on a Chinese temple. This very inclusive structure, persisting in its oddities to the end, makes a great point of staring down at the gaping crowds out of a big belfry clock that has one dial Hebrew and one Christian. But a single marvel is as nothing in this old wonderland where, as Alice would have remarked, things become “curiouser and curiouser.”

If your eyes popped at the Rathaus what will they do at the gaunt, barnlike synagogue next door! Here is the thing that every visitor to Prague goes straight to see. Its early history is lost in legends, but you will be disposed to credit them all — even to that one about the Prague Jews fleeing from Jerusalem to escape the persecutions of Titus — once you have seen its doleful walls and breakneck roof, and have passed through the narrow black doorway into that shadowy tomb of an interior. Brass lamps depend by long chains from the smoky ceiling, but they only intensify the gloom with their feeble light and deepen the feeling of creepy depression.

Visitors are told that during the horrors of the Hussite wars this black hole was literally packed with the bloody corpses of Jews and that, in a bitter spirit of defiance, no attempt was made for three hundred years to efface the frightful stains. Little wonder that the Prague Jews evolved out of their hatred an ancient malediction that ran: “May your head be as thick as the walls of the Hradschin, your body grow as big as the city of Prague; may your limbs wither away to birds’ claws, and may you flee around the world for a thousand years!”

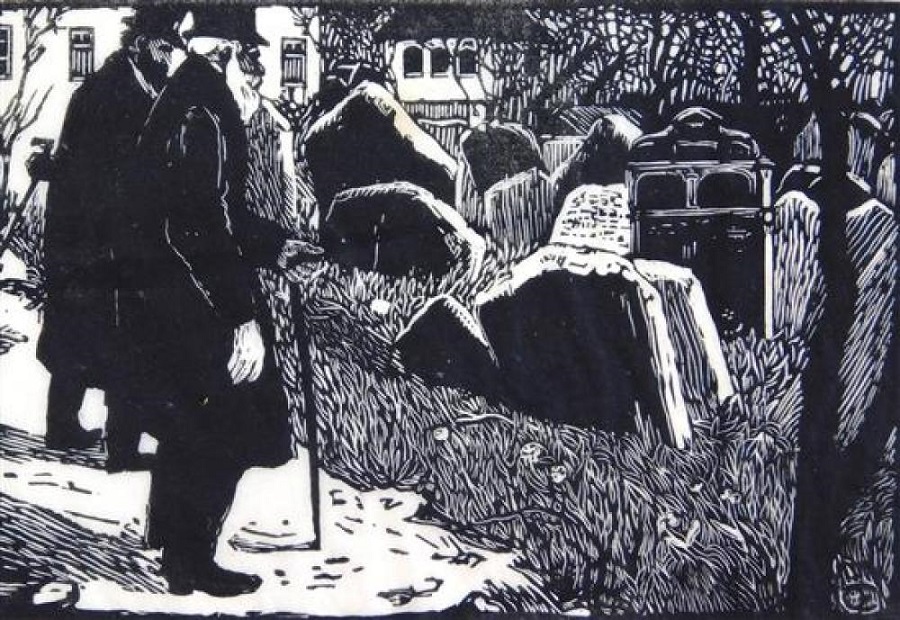

It is like escaping from a sick-bed to come out of this chamber of horrors and cross the street to the quiet and hush of the wonderful old Ghetto cemetery. Here we have another of the “sights” of the Josephstadt. In the refreshing coolness of its elder-trees one looks about on as extraordinary a three acres as can be found anywhere in all Europe. The Jews insist that they have buried here for twelve or fourteen hundred years, and inscriptions can be found that date back at least half that far. By the simple process of spreading new layers of earth, this plot has been packed with graves six deep; and all that was accomplished a hundred and fifty years ago, the cemetery not having been in use since the middle of the eighteenth century. The closeness of the black, mossy tombstones, and their toppled and huddled look, suggest the troubled shouldering of some gigantic, ghoulish mole at work deep down in the horror-crowded darkness underground. The ancient tribal insignia of Israel are found graven on these tottering slabs, — the Hands of Aaron, the Cup of Levi, the Double Triangle of David, the Stag, the Fish, etc., — and here and there you come across those little’ piles of stones heaped on graves that mark a Jewish act of reverence for the resting-place of some long-buried ancestor.

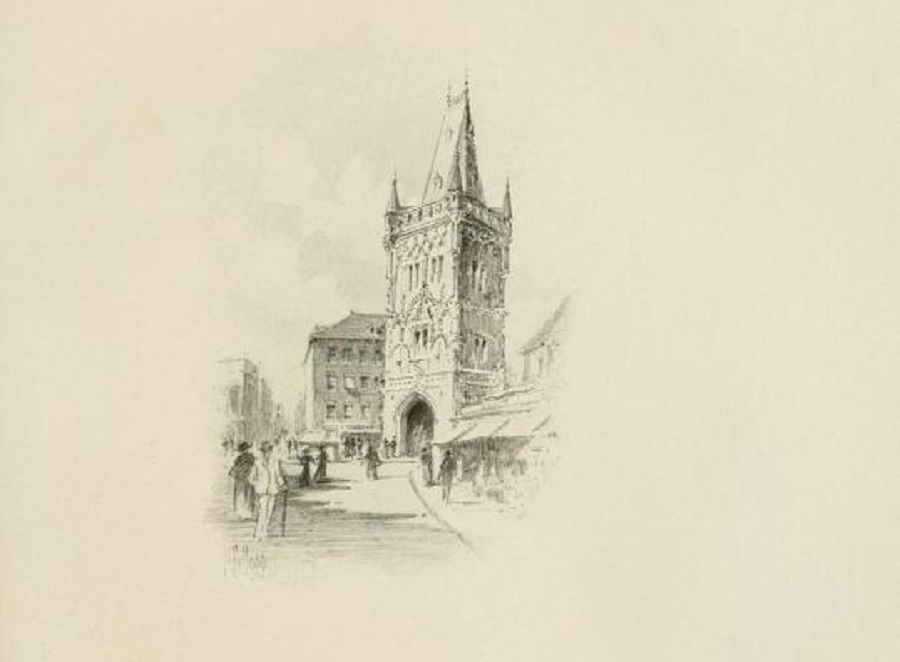

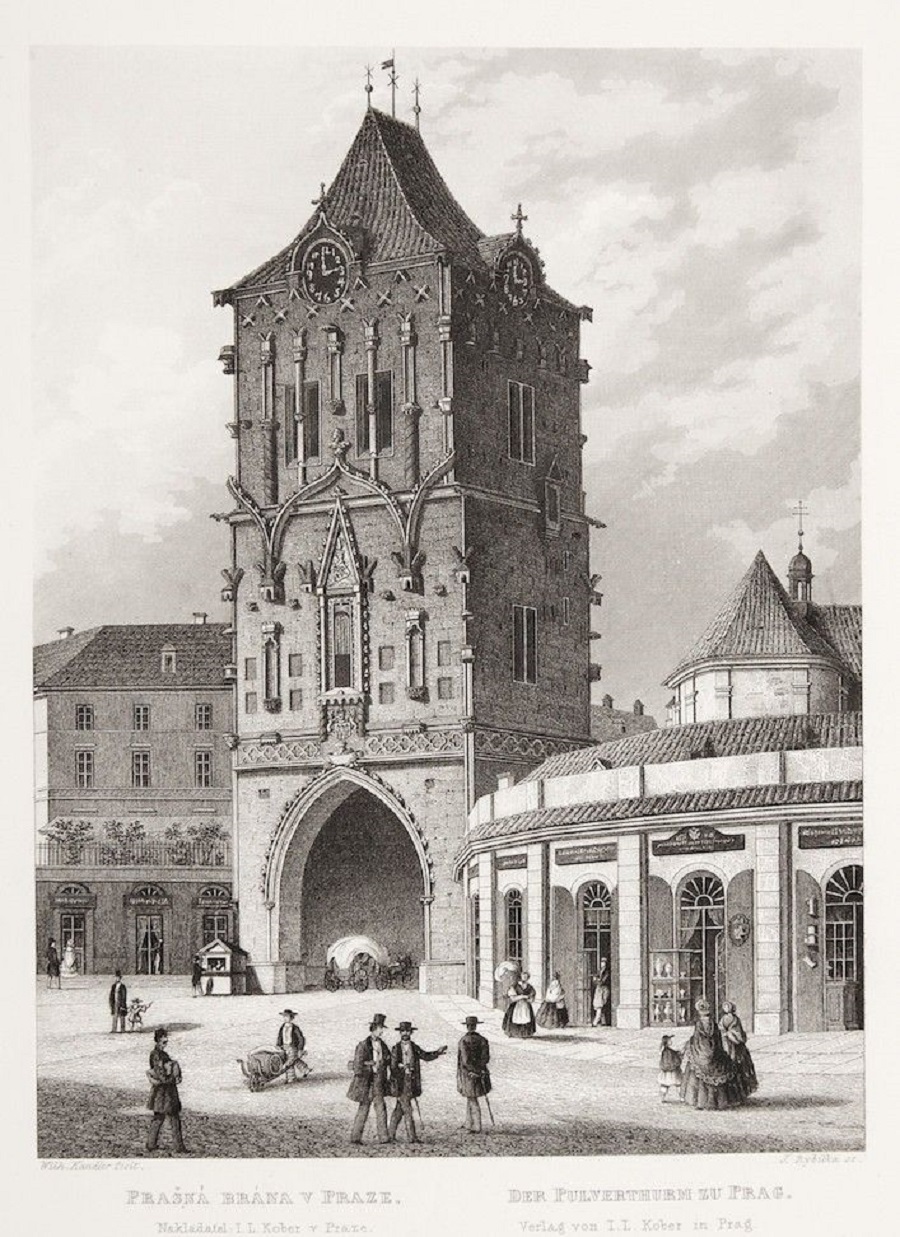

Hold to a generally southern direction in your afternoon stroll through the narrow Ghetto alleys, and shortly you will meet with a fine reward in the shape of a face-to-face contemplation of one of Prague’s most cherished antiquities, the Pulverturm*. They may have once stored powder here, as the name implies, or they may not; but almost anything looks to have been possible to this sturdy, brown survivor of the Middle Ages, under whose broad Gothic archway the twentieth-century crowds are passing day and night. Set solidly down in the thickest stream of traffic, it has the look of those unconquerable obstructions that have to be tunneled through. It looms above you, a great, dark, dusty mass, out-of-time in every particularity of design and decoration. Stubbornness and defiance are expressed in every line; and with its atmosphere of drowsy aloofness and mystery there is such an element of loneliness among such modern surroundings that one could almost believe he sometimes hears the old veteran sigh. Certainly you would say it is brooding over memories centuries dead, so incongruous and distrait is its seeming, so anachronous are its whimsical turrets, fantastic roof, statues, arms, and sculptured traceries. This impression of isolation is enhanced as one reflects that the most ultra-modern of Prague’s new buildings all stand within easy range, could one of the Pulverturm’s ancient archers take up a position in any of those lofty turrets and wing an arrow from his stout crossbow toward what quarter of the heavens he chose.

(I*Note: The Powder Tower, Powder Gate or Prašná brána) is a Gothic tower in Prague, Czech Republic. It is one of the original city gates. It separates the Old Town from the New Town. The Powder Tower is one of the original 13 city gates in Old Town, Prague. Its construction began in 1475. The tower was intended to be an attractive entrance into the city, instead of a defensive tower. The foundation stone was placed by Vladislav II. The city council gave Vladislav II the tower as a coronation gift.)

When you have passed under the arch of the Pulverturm, you have entered the Graben, and so reached the business heart of the city. The Graben has nothing toay to suggest the “Ditch” that its derivative source implies, unless you fancifully regard it as a moat of the modern commercial ramparts. On the contrary, it presents a busy array of all the leading hotels, shops, restaurants, and cafes. Overhead-trolley cars splutter along it, and you see gray stone buildings of irregular roof -lines with skylight dormers in the tiles, and Veneian blinds in the windows, narrow sidewalks decorated in mosaic designs, and active throngs of strong-featured men, and bareheaded, vigorous women whose chief pride of dress concerns itself with capacious aprons elaborately embroidered. Were you to visit the second-story cafes, whose gay window-boxes look so inviting from the street, you would find games of chess and checkers in progress at this hour, and more than one merchant who had stolen from his shop to have a look at the “Prager Tagblatt” over a glass of Pilsener or “three fingers” of the plum brandy they call slivovitz or a dram of tshai — which is tea and rum — or a cup of tee — which is just plain tea and cream. Coffee and chocolate, of course, would be found in general demand.

One passes out of the Graben into the fine boulevard of the Wenzelsplatz, and at once exchanges bustle and uproar for the quiet and dignity of the most beautiful and stately avenue of the city. It is broad and well-paved, with buildings of elaborate design, with shop fronts protected by bright awnings and with fine shade-trees every few yards along its entire length. At the corner of the Stadt Park, one finds a beautiful cascade fountain, and beside it a noble building which is the center of all that is best and most intense in the new movement for the reviving and vitalizing of the national spirit among Bohemians — the new Bohemian Museum. Were you to enter it you would doubtless be astonished to see how many souvenirs of Bohemian history have already been assembled there, — autographs and documents, ancient musical instruments, art objects, flails of the Hussites, and scientific collections. Such is the intellectual Bohemia of today.

From this pleasant stroll one wends his way back to the Karlsbrucke, and as he passes the buildings that still remain of the ancient famous university, thoughts are kindled of the wonderful renown this institution had, six centuries ago, when it was easily the foremost educational institution of the world (Charles University in Prague or Univerzita Karlova.) Fifteen thousand students, from every quarter of the earth, gathered to hear its celebrated savants, and the revels and achievements of those days have gone down in prose and rhyme. Five thousand students still attend, two thirds of them Czechs and the others German; but the revelry of today is largely the bitter and bruising encounters that are continually arising between these conflicting hot-heads. The intellectual impulse is strong in Prague. It has polytechnic institutes, art schools, and learned societies, and one of the most famous conservatories of music in the whole of Europe.

The west bank of the Moldau, the Kleinseite district, was royalty’s region in the olden time when Bohemian kings and queens dwelt in the huge Hradschin on the ridge of the hill. Seen from the Karlsbriicke, toward five o’clock, the long slope rises toward the declining un with many more suggestions, even now, of the pomp and circumstance that have departed than of the modernism that has taken their place. There is a dreary and saddening array of closed and boarded palaces, arcaded and many-windowed, whose owners are rich and powerful Bohemian nobles with a preference for the gayeties and frivolities of the court life of Vienna.

One regards with especial interest the long, rambling one of Wallenstein, to make room for which one hundred houses had to be torn down, where this rival of royalty retired in the interval of imperial disfavor and held magnificent court with hundreds of followers and attendants. Among the many chambers of that great honeycomb was one equipped as an astrological cabinet — for Wallenstein always had faith in his star. How vividly it recalls the Schiller dramas and the operations of the uncanny Ceni! “Such a man!” exclaims a character at the conclusion of “Wallensteins Tod.” Born a Protestant, he well-nigh became their exterminator; turned Jesuit, the Jesuits distrusted and hated him. With his sword he made and unmade kings and carved out principalities for himself — and yet he was but fifty-one years old at the time of his assassination!

Like an aged soldier nodding in his armchair in the sun, the Wallenstein Palace (Valdštejnský palác), once passion-rocked and treachery -haunted, basks this afternoon in an atmosphere of the intensest calm and peace. To ramble through it is to learn history from a participant. One courtyard, in particular, is so serene and lovely as to be really unforgettable. One entire side of this enclosure is a lofty, echoing loggia three stories high, with arching spans for a roof supported on graceful, towering columns. Within the loggia are heavy sculptured balustrades, and a broad flight of marble steps flanked by huge stone urns leads to a beautiful open space of soft lawns bordered with simple flowers. It was a favorite resort of Wallenstein’s, and he called it his sala terrina. In its present mellow and half-deserted beauty it is a place for a poet to dream way a life in.

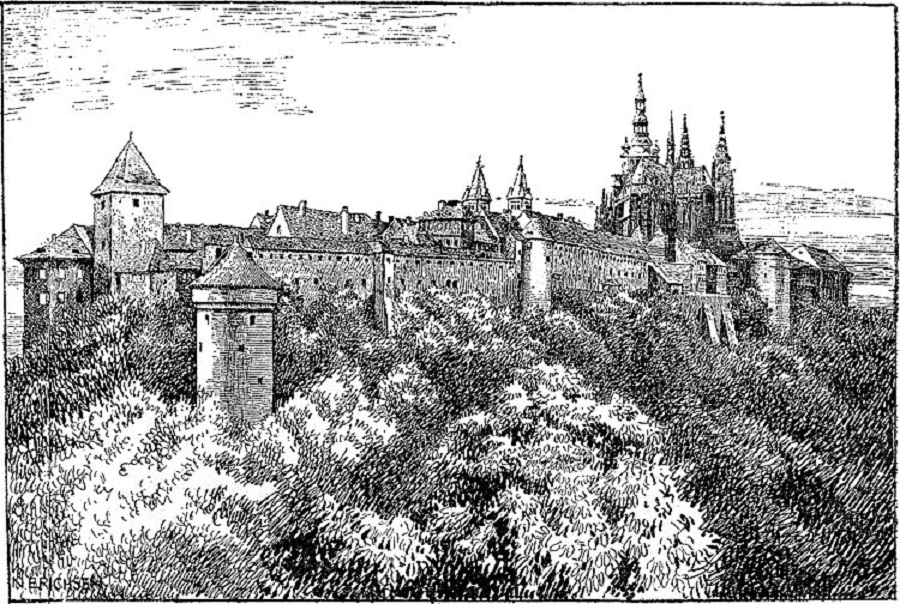

Staring gloomily down on the Kleinseite, and set solidly far above it on a precipitous hill, the rugged old Hradschin, Prague’s acropolis, warms into mild ruddy tones in the afternoon sun. I have said it reminds one of a barracks, such an enormous, rambling affair as it is; though its commanding situation and impressive proportions would immediately suggest to a stranger some more consequential employment in other days.

(Note: You may wish to read Where Nerudova Street Got its Name.)

Undoubtedly it is the most striking feature of Prague. One might think it a solid architectural mass, as seen from the Karlsbriicke, but on closer inspection it resolves itself into a series of separate structures falling into irregular groups, but which, taken together, composed the setting of the imperial court during the long period of Bohemia’s independence.

That splendid fragment, the vast cathedral of St. Vitus, supplies a worthy centerpiece; and is full of interest, too, with its rich Gothic windows, chapel walls set with precious stones, marble tombs of the Bohemian kings, and the wonderful silver monument to St. John Nepomuc. Indeed, the whole Hradschin abounds in rich surprises. Such, for instance, is the venerable church of St. George, awkward and archaic, which has stood for nine hundred years and is the sole memorial in Bohemia of the earliest period of Romanic architecture.

Every one, of course, hurries up to see the rude royal palace of the Hofburg, on the edge of an adjacent steep hill, from the windows of whose Kanzlei Zimmer the Imperial Councilors were “defenestrated” and the Thirty Years’ War, in consequence, precipitated upon the troubled states of Europe. And then there is the archbishop’s palace, across the quadrangle from the Hofburg, in whose courtyard the church authorities impotently burned the two hundred Wycliffe books that John Hus had loaned them with the challenge to read and, if they could, refute.

Two grim towers on the eastern extremity, the Daliborka and the Black Tower, have no end of creepy legends of tortures and prison horrors. The former takes its name from a romantic knight, Dalibor, who is said to have been long confined there and of whom and his solacing violin we hear at pleasant length in Smetana’s opera of that name.

One of the most curious sights of the Hradschin is the low, drawn-out Loretto* church, with a maximum of frontage and a minimum of depth, like city seminaries for young ladies. Among the red tiles of its steep roof, giant stone saints perform miracles of precarious footing, and out of the center of the facade, on a base of colossal spirals, rises an antique belfry spire set with domes and turrets and bearing aloft a huge clock dial like a burnished shield. Surely, somewhere in this Hradschin-wonderland occurred the unrecounted events of that much-interrupted narrative of the “King of Bohemia and his even Castles,” which Trim tried so hard to tell to Uncle Toby Shandy; and may we not be confident that the charming Prince Florizel, whose strange adventures Stevenson has so gracefully recounted, once lived and courted perils in these romantic surroundings!

(*Note: Loreta is a pilgrimage destination in Hradčany, a district of Prague, Czech Republic. It consists of a cloister, the church of the Lord’s Birth, the Santa Casa and a clock tower with a famous chime.)

It is to be hoped that every visitor will have more than one hour in Prague; and then, of course, he will want to go up to the Hradschin and loiter through and about it at his leisure. He will find large and beautiful gardens where he can rest under noble trees and enjoy an inspiring view of the city in the pleasant companionship of statuary and fountains. When he has exhausted this viewpoint he can secure quite another from the colonnaded verandas of the Renaissance Belvedere; or, perhaps better still, he will journey out to the picturesque Abbey of Strahow (Strahov Monastery or Strahovský klášter), embowered in blooming orchards that are vocal with blackbirds, and from its yellow stuccoed walls look down on the dense forests of the Laurenzberg (Petřín Hill) sweeping in billowy green to the very banks of the Moldau.

At this hour a sharp point of light, seen from the observation tower on the summit of the Hasenberg (Nebozízek), marks the location of a little white church on a distant hilltop — and when you have been told all about what happened there at the fatal battle of the White Hill you will have listened to the bitterest chapter in the whole history of Bohemia and will know how the national life of this kingdom gasped itself out, three centuries ago, in the panic and rout of the ” Winter King’s ” ill-managed soldiery before the fierce infantry of Bavaria.

There fell the state won by the flails of a fanatical peasantry whose sonorous war-hymn, “Ye Who Are God’s Warriors,” had so often struck terror into the ranks of the finest armies of Europe. Those were the men whom the furious Ziska (Jan Žižka) led — Ziska, the squat and one-eyed, the friend and avenger of Hus; “John Ziska of the Chalice, Commander in the Hope of God of the Taborites.” Such was the terror in which this dread chieftain was held by his foes that they feared him even after his death and declared that his skin had been stretched for drum-heads to summon his followers on to victory.

Since the battle of the White Hill there has been little for Prague in the way of war except sieges and captures ; and it has mattered little to her whether it was Maria Theresa come to be crowned, or Frederick the Great come to destroy, or the Swedes of Gustavus Adolphus come to plague and offend. Suffering has been her regular portion. During the Thirty Years’ War alone, Bohemia’s population declined from four million to fewer than seven hundred thousand.

The stranger on the Karlsbriicke will turn from thoughts of Ziska’s peasants to regard with increased interest the occasional specimen of the countryman who strides past along the bridge with no embarrassment at appearing in the streets of his capital in the costume of his nation. Behold him in his high boots, tight buff trousers, well-embroidered, blue bolero jacket with many buttons, broad lapels and embroidered cuffs, his soft shirt puffed out like a pigeon, and the jaunty Astrachan cap cocked to one side. And there, too, marches his wife; boots laced high, bodice bright and abbreviated, petticoats short and broad and covered by a wide-bordered apron, her arms bare to the shoulders, and her headdress of white linen very starchy and stiff. Sometimes one passes wearing a hat that suggests Spain, but he, too, as they all do, wears the tight trousers and the close-fitting knee boots. In time one learns to distinguish the Slovaks and Moravians by their long, sleeveless white coats, tight blue trousers, and white jackets with lapels and cuffs embroidered in red.

One hears many interesting things about these peasants. Throughout the year, it is said, they fare frugally on black bread and a cheese made of sheeps’ milk, to which is added an occasional trout from the mountain streams. The great age some of them attain speaks well for the diet. Strangers who go up into the hills to stalk chamois and have a go at the big game come back with surprising stories of the inherited deference that is still paid in the country to caste. They will tell you that the peasant still kisses the hand of the lord of the soil. The Praguer thinks highly of his country brother, though he finds a vast amusement in observing his rustic antics when he comes to town on St. John Nepomuc’s Day and shuffles about the streets, wide-eyed and gaping, after the manner of rus in urbe the world over.

Curious stories are told of peasant customs. Christmas is their day of days, and preparations for its proper observance are made long in advance. They believe it to be a season when evil spirits are powerless to injure and may even be made to aid. When the great day arrives, the cottages are scrupulously cleaned, fresh straw laid on the earthen floor, and the entire household assembled for a processional round of the outbuildings. In the course of this ceremonial parade, beans are carefully dropped into cracks and chinks of the buildings, with elaborate incantations for protection against fires. Bread and salt are offered to every animal on the place. The unmarried daughters are sprinkled with honey-water to insure them faithful and sweet-natured husbands. The family drink of celebration is the plum-distilled slivovitz.

(You may be interested in A Look Back at Czechoslovakia Before World War I.)

What effective use the great national composers of Bohemia — Smetana, Dvorak, and Fibich — have made of the native melodies and costumes! Smetana, a friend and protege of Liszt, — the master utilizer of Hungarian folk-themes, — was determined that Bohemia, too, should have music of a distinctively national character; and in his eight operas and six symphonic poems, as well as in his beautiful stringed quartette, the “Carnival of Prague,” he abundantly realized his ambition. There is no more popular opera played in Prague today than his “Bartered Bride.” One hears a great deal of Smetana in talking with the people of this city; of his poverty and sadness, his final deafness, and of how, when fame at last crowned him so completely, he was dying in an asylum here.

Music is a favorite topic of conversation in Prague. A violin player in one of the local theatre orchestras was no less a person than the great Dvorak, a pupil of Smetana’s; and he, too, added to Bohemian musical glory with his Slavonic rhapsodies and dances and the splendid overture that he constructed on the folk-melody “Kde Domov Muj.” There was a sort of Bach-like foundation for all these composers in the early litanies f the talented Bishop of Prague. The Czech temperament finds its natural expression in music. It is even insisted that their most popular movement, the polka, was invented by a Bohemian servant girl*.

(*Note: The first polka was written by František Matěj Hilmar. You can read about it at this link: František Hilmar, Father of the Polka)

Certainly there has been no lack of beautiful legendary material on which to construct effective compositions. These traditional stories are all full of sadness and superstition, and they always revolve about simple, natural elements — the rain, the mountains, the valleys, ghosts, and wild hunters, and, above all, that most recurrent and universal of themes, love.

Could we win favor with some old Praguer this afternoon and entice him into the sunny corner of Karl IV’s monument place, beside the bridge, we should close out our hour with many a captivating and romantic story that would alone have made our visit well worth while.

Such, for example, is the legend of the “Spinning Girl.” Deserted by her lover, she wove a wonderful shroud threaded with moonbeams, and in this she was buried, and by its magic she appeared to him on his wedding night and lured him to leap to his death in the river. And there is the story of the “Wedding Shirt”: A girl implores the Virgin either to let her die or restore her absent lover who, unknown to her, has been dead some time. The Virgin bows from the holy picture, and forthwith the pallid lover appears and conducts his sweetheart by a midnight journey to the spot where his body lies buried. Thereupon ensues a desperate struggle by fiends and ghouls to capture the soul of the girl, who is finally rescued by the interposition of the Virgin to whom in her terror she appeals. The wedding shirts that she had brought as her bridal portion are found scattered in fragments by the sinister spirits on the surrounding graves. The flight of the maid and her ghostly lover is vividly depicted at length, and is expressed, in translation, by such lurid lines as — “O’er the marshes the corpse-lights shone, Ghastly blue they glimmered alone.”

One of the most romantic of these legends is the “Golden Spinning-Wheel.” A king loses his way while hunting and stops for a drink at a peasant’s cottage. There he finds a marvelously beautiful girl, to whom he eagerly offers himself in marriage. This girl is an orphan, with a stepmother and stepsister who are cruel and jealous. Under pretense of accompanying her to the king’s castle they lure her into a black forest and slay her, taking great pains to conceal her identity by removing and carrying with them her eyes, hands, and feet. They then proceed to the castle and the wicked daughter successfully impersonates the good one, whom she closely resembles. Seven days of wedding festivities ensue, at the end of which the king is called away to the wars. In the mean while a mysterious hermit — a heavenly messenger in disguise — takes up the dead body in the forest, dispatches his lad to the castle and secures the eyes, hands, and feet by bartering for them a golden spinning-wheel, a golden distaff, and a magic whirl. hus equipped, he miraculously restores the girl to life and limb. When the king returns from the wars he invites his false bride to spin for him with her new golden wheel, and forthwith the magic instrument sings aloud the whole miserable story. The furious king rushes to the forest, finds his real sweetheart, and installs her in his castle, while the murderers are mutilated as she had been, and cast to the wild wolves.

It may be thought that I have gone somewhat out of my allotted way in taking such notice as I have of the superstitions, customs, and music passion of the Bohemians, but I cannot believe that a satisfactory idea of Prague can be had in this, or any other hour, without some conception of the fundamental traits that so powerfully sway this people.

For the real significance of the city lies deeper than its surface-showing of wooded hillsides sown with quaint buildings and a broad blue river rushing under many bridges; it is its peculiar raciness of the soil that underlies the Czech’s mad devotion to his capital. Expressing, as only Prague does, so much that is dear and beautiful to him, it centers in itself the most burning and passionate interests of the race. Without some knowledge of this desperate attachment one would fail utterly to grasp the force and truth of such a fine observation as Mr. Arthur Symons has made on the devotion of the Bohemian to this city: “He sees it, as a man sees the woman he loves, with her first beauty; and he loves it, as a man loves a woman, more for what she has suffered.*”

(*Note: In the summers of 1897 and 1899, the British decadent poet and critic Arthur Symons visited Prague. His impressions were mixed. Underneath a “modern Prague … in the image of Vienna”, he wrote, “the Bohemian still sees a phantom city”, a “strange” and “sombre” place. He found uncanniness in Prague’s traces of the Gothic and Baroque, and described them in ways that echo his own earlier characterization of decadent literature as a blend of “over-subtilizing refinement upon refinement”, “spiritual and moral perversity” and fantasy. “Bernini in his most fantastic mood never conceived anything so fantastic [as Charles Bridge]”, Symons claimed; the Jewish quarter, especially the cemetery with its haphazard layering of antique graves, offered an eerie melancholy.” Source.)

We love our beloved Prague, and cannot wait to return.

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Thank you in advance!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.