Have you ever wondered what the big deal is with Czech Tramping? Why do they walk around with cowboy hats or military fatigues? Who are they, and what kind of a movement it is? The following was written by Jan Pohunek of the Institute of Ethnology, Faculty of Arts, Charles University, Prague, Czech Republic. It was published in FOLKLORICA 2011, Vol. XVI. It is reprinted here with permission of Jan Pohunek, to whom we are very grateful. (Note: The photos and videos in this post have been added by us, Tres Bohemes.) We recommend you read it all the way through.

The article describes the history and major characteristics of an independent Czech youth movement called “tramping.” The movement originated in the 1910s-1920s as an unorganized offshoot of boy scouting and E. T. Seton’s Woodcraft and quickly became popular among urban teens and young adults. It was simply a way of spending time outdoors with friends at first, heavily influenced by early Western movies and Wild West aesthetics in general, but it became a distinctive subculture and cultural phenomenon during the following decades. Some of its unique aspects include specific music, slang, art, and dress code.

Czech tramping is also an interesting example of an early youth subculture, which is comparable to post-WW2 subcultures and which survived into the present day, although its participants were often persecuted, especially under the communist regime. Another topic discussed is the fact that the movement kept its independence even under political pressure, rejected all attempts to organize it hierarchically, and while it sometimes had a dimension of protest culture in the 20th century, it can be considered to be apolitical in general.

The Czech Tramping Hymn

It is now almost a hundred years since an interesting modern folk cultural phenomenon began to establish itself in Bohemia. ‘Tramping’ (1), as it is called nowadays, can be described as an unorganized youth >movement, or a subculture, that is heavily inspired by the romantic image of the American Wild West, and that manifests itself mostly through outdoor social activities such as hiking or camping, accompanied by specific styles of music, slang, architecture, art and clothing.

The tramping phenomenon has influenced modern Czech folklore and mainstream culture, but it has also always been on the brink of legality. This article attempts to present an overview of the history of the movement, its characteristics, and its importance to social anthropology and folklore studies.

AHOJ KAMARÁDE, Settlers club, 1931

The history of tramping in Bohemia is tied to the history of scoutlike youth movements and modern outdoor sports activities. Organizations related to outdoor sports were becoming increasingly popular in Czech society during the 1880s. Some of them were inspired by universal gymnastic movements, especially by their precursor Sokol (2), while others, like the Czech tourist club or clubs of first skiers, were more related to specific emerging sports. Some of these organizations also had their own divisions for children and young adults. Both Lord Baden-Powell’s boy scouting and E. T. Seton’s Woodcraft movements were introduced as a novelty in 1912 by various enthusiasts [Břečka 1999: 11-12].

However, there were also groups of young people, including some former Boy Scouts, who were inspired by these movements and interested in hiking and camping regularly but disliked the tight control and official nature of established organizations. Such groups of “friends” (kamarádi), usually factory workers, apprentice craftsmen, or students, spent their weekends camping in wooded, romantic valleys in the area south of Prague [Hurikán 1990: 14-15; Moidl and Moidlová 2010: 10].

A significant increase in the number of these unorganized campers came after the end of the First World War and the formation of Czechoslovakia. Camping and hiking became more popular among young people from Prague and, increasingly, from other large cities. The reason was that such activities allowed young people to spend weekends together in nature without having to belong to an official organization. The experience of the war contributed to both their desire for personal freedom and their outdoor skills. Another key factor in this process was the notable increase of the influence of American culture, a phenomenon related to American support for the young Czechoslovakia, to the post-war international importance of the United States, and also to the activities of organizations like the YMCA. Films and novels contributed to the popularity of things American as Westerns were imported in great numbers and attracted large audiences (3) [Waic and Kössl 1992: 9, 12-22; Břečka 1999: 11].

Young independent campers were called “wild scouts” because the number of former Boy Scouts had increased after the war. Most of these were recruited from the first generations of Boy Scouts who had outgrown their early teenage years. The concept of rovering as a way to keep such people attracted to scouting even as they become young adults did not fully develop until after 1917 [Břečka 1999: 43], and scouting organizations, with the exception of a few leading Boy Scout clubs, had little to offer them.

The “wild scouts” quickly embraced the romantic life of the Wild West and did so in a playful manner, seeing it as a kind of game or a weekend lifestyle (4). They introduced Western-like items of clothing into their camping equipment, which otherwise consisted mostly of civilian and army surplus clothing. The specifically Western pieces of clothing included studded wide belts, brass sheriff stars, and “Stetsons” created by refashioning old hats; all were homemade. Some groups of “wild scouts” combined their garments in an eclectic manner while others kept a unified style, for example, dressing in black cowboy-like clothing heavily inspired by Tom Mix movies. M1910 US army haversacks became quite popular at this time and became one of the “trademarks” of the movement in the following decades(5) [Hurikán 1990: 19-21; Waic and Kössl 1992: 63; Moidl and Moidlová 2010: 11; description of the haversack available at Rottman and Volstad 1989].

These groups of wild scouts also began to use permanent camping places, sometimes with the consent of the landowner and sometimes without. Cover names were occasionally used for dealing with the authorities when renting a place for camping. Such names included “The Table Fellowship,” “The Fellowship of Filmmakers,” “The Friends of America,” “The Settled Scouts,” and even “The Association of Catholics of the municipality of Prague.” Many names had aspects of a practical joke [Hurikán 1990: 55].

Tents, simple huts, and log cabins were erected, and the term Osada (“settlement” or “colony”) began to be used for both a particular place and the group >linked to it. Osadas adopted romantic names (6) and had their own symbolism, which was represented by flags, badges, and similar items. However, the transition from hiking (7) to sedentary camping was not universal – less frequently visited, smaller, more simple, and rent-free campsites, called campy or kempy, remained in use, especially in areas where it was not possible or necessary to build a larger cabin osada.

The term “wild scouts,” used to describe these campers, was perceived as somewhat pejorative, and around the mid-1920s, they began to call themselves trampové, with the word tramp likely taken from the works of Jack London. The movement spread into other cities during the second half of the 1920s, and its popularity was increased even more by the Great Depression, which forced more people to spend their free time on a low budget. Tramp campsites became centers for amateur sports such as volleyball, canoeing, and even boxing, and for social and cultural life [Waic and Kössl 1992: 14-16, 23-24, 64; Hurikán 1990: 16-19, 23-25; for regional examples see Vinklát 2004: 17; Krško 2008: 13].

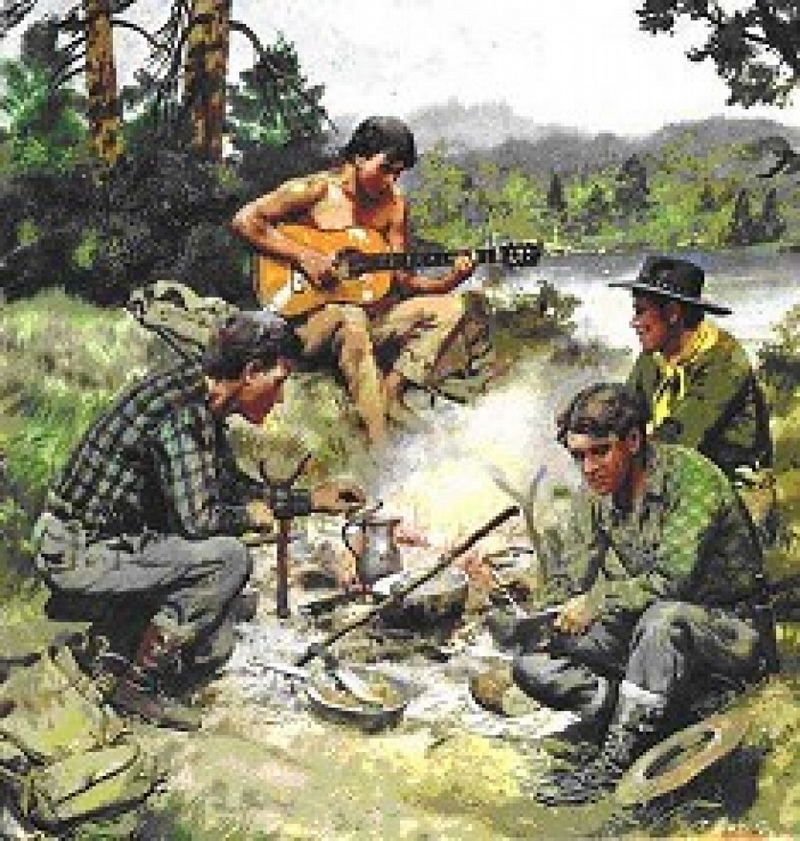

Performing music was especially popular. Initially, “wild scouts” used to sing military-themed songs describing the hard life of soldiers, national and folk songs, and contemporary Czech and American hits. They especially favored melodramatic pieces. The most popular musical instrument was the guitar, but others like the violin, accordion, banjo, or comb were also used. This song repertoire was soon partially replaced with new songs made up by the tramps themselves. At first, these were only rewritten versions of older songs, but with time the song repertoire evolved into a distinct and original genre of “traditional tramp songs”.

These original songs were often created by amateur composers and writers with professional (8) skills. Traditional tramp songs were still heavily musically inspired by contemporary popular music but were usually composed for the guitar and were intended to be sung together by friends around the campfire. Texts of the first original tramp songs were often semi-anonymous and spread and evolved both as oral folklore and through hand-written songbooks (řevníky – “roarbooks”). The typical subject matter of these songs was either humorous or sentimental [Waic and Kössl 1992: 66-67; Mácha 1967: 6 et seq., 26 et seq.; Noha 2007: 22-23].

The word potlach (a word-play on the American Northwestern native term potlatch and Czech verb tlachat – to tattle) was used to describe larger and more ceremonial tramp meetings that included activities such as playing music, reading short stories and poetry, and playing various games by the campfire. Campfires lit at potlachs had a “sacred” status inspired by the symbolism of E. T. Seton’s Woodcraft. To wit, the campfire was usually placed in a decorative stone circle, and it was forbidden to use it for “profane” activities such as burning waste and cooking.

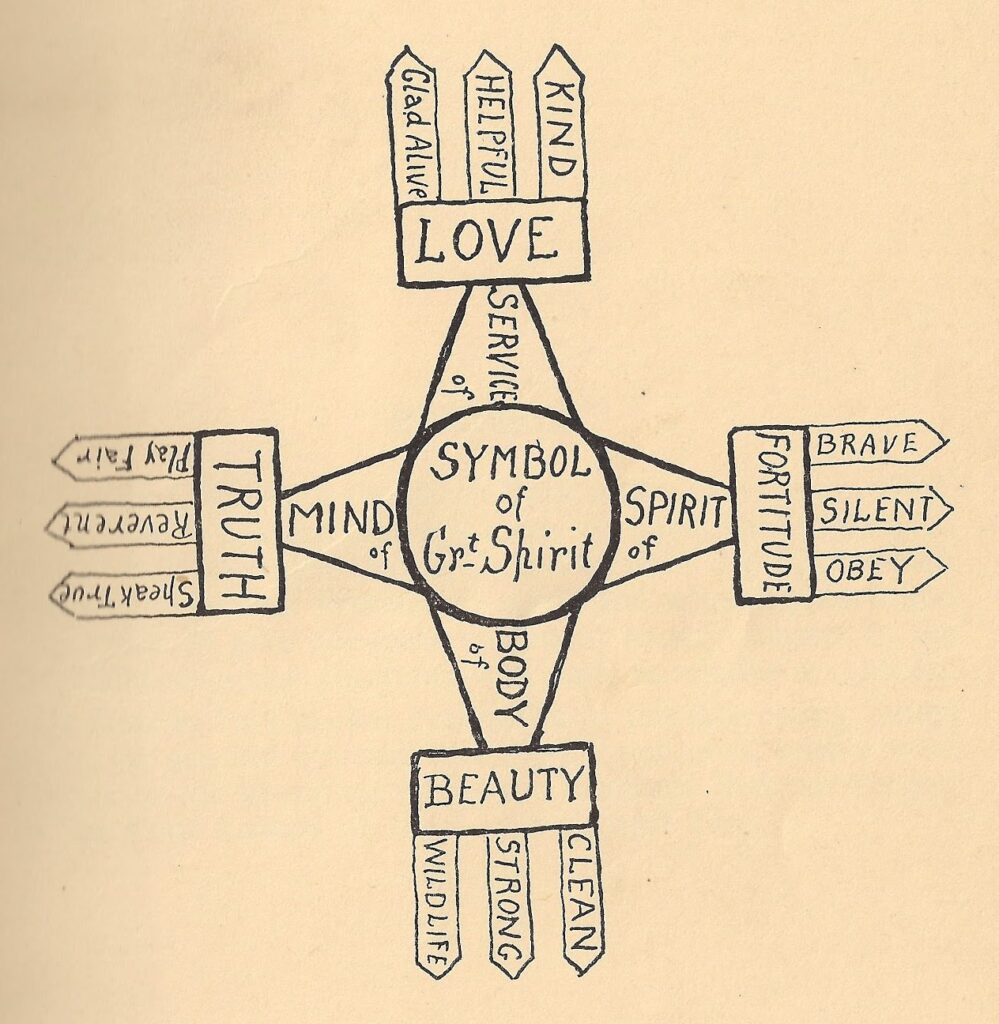

The symbol of Woodcraft – a circle with buffalo horns – was later (possibly as late as after WW2) adopted as a symbol of tramping.

Other communal activities of tramps included sports tournaments, meetings in country pubs, and playing practical jokes. Typical practical jokes popular among tramps were called kanadské žertíky (Canadian jokes). These were usually attempts to disconcert friends or other groups of tramps in a funny way, sometimes even in a rather harsh but socially acceptable manner. A “Canadian joke” had to be accepted stoically and repaid in kind when possible.

The tramp movement and mainstream culture often found themselves in conflict for a number of reasons. There was a strong leftwing, or even pro-communist faction in tramping, including some people who dressed in a “Soviet” style and used Red Army equipment and Communist badges. This styling was, however, more romantic than violent or radical. It should also be noted that some tramps joined the Interbrigades in the Spanish Civil War. But while this left-wing faction was notable, tramping remained apolitical and unorganized on the whole. [Waic and Kössl 1992: 45-49, 91-92; Krško 2008: 89-102; Noha 2007: 29-30]

Tramps were seen as a disturbance by many figures of authority either because of their disrespect for rules or because of their supposed low level of morals, even though tramping was not fundamentally anti-system, nor was it a free love movement. It was, however, part of the more liberal wing on the First Republic’s social scale. Tramps were both welcomed in the countryside because tourism as a whole increased revenue in poor regions and shunned because they did not behave “properly” and were sometimes, often unjustifiably, suspected of petty thievery and misbehavior.

The most important attempt to get tramping under control was the “Kubát’s Law” of 1931, a decree of the Czech provincial president Hugo Kubát, which forbade unmarried couples camping together, swimming where prohibited, and swimming without proper bathing attire. It also outlawed the carrying of firearms and the singing of “indecent” songs. This decree led to an increase in the persecution of tramps by the gendarmerie and also inspired unsuccessful attempts to organize the movement to increase its importance. These attempts mostly originated among left-wing tramps, but all of them were short-lived and did not succeed in encompassing the majority of tramping culture. [Waic and Kössl 1992: 37-60; Hurikán 1990: 246-247]

The decree of 1931 was ruled to be unconstitutional by the Supreme Court in 1935 [Hurikán 1990: 247], and tramping rapidly became even more widespread, reaching more regions, Slovakia included, and encompassing more social classes. It became a part of the recognized popular culture in the 1930s, especially because of the popularity of prolific singers and composers of tramp music, some of whom became professional performers. Some tramp music was performed by professional singers who were not tramps.

(Note: We’ve written posts about this before. See Czech Tramp (Tramping) News Covers from 1930 and Tramp Music Songbook Covers Pre-1940s – links open in a new window.)

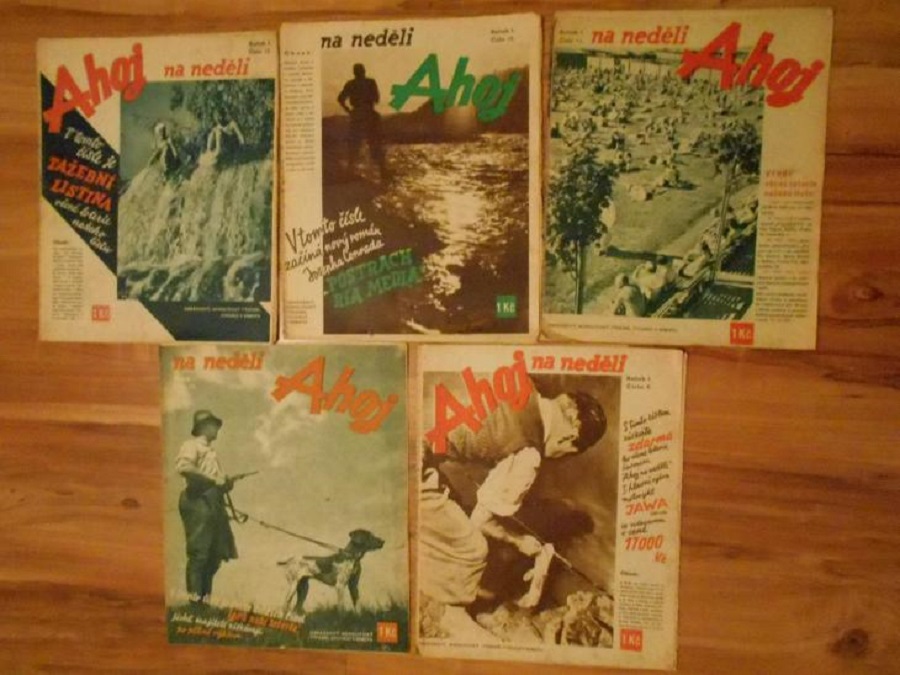

The movement, while still viewed ambivalently by the authorities, prospered. More magazines published by tramps and for tramps, like Tramp, Naše osady (Our colonies) or pages in Ahoj na neděli (Ahoy for Sunday), were printed on both amateur and commercial levels [Hurikán 1990: 230-232].

(Note: See 1929 Tramp Magazine covers here – opens a new window.)

Sports and clothing shops sold professionally manufactured equipment for tramping. Movies and books about Czech tramps were two more indications of tramping’s public acceptance. There were, however, rumors that the movement was losing its edge and becoming too close to mainstream culture. (9) [Waic and Köosl 1992: 33-34]

The Nazi occupation of the former Czechoslovakia and the Second World War did not influence tramping directly; being a tramp was not in and of itself a reason to be persecuted, but the personal freedoms associated with this pass time were limited, and some tramps drew suspicion to themselves by participating in resistance activities or joining foreign armies [Waic and Kössl 1992: 91-98; Noha 2007: 34-36]. More intensive persecution, leading to a temporary decline in tramping, came in the 1950s after the Communist coup d’état of 1948. The Communist regime attempted to destroy or control all youth movements, replacing them with a unified supplemental education model based on the Organization of Young Pioneers (Pionýrská organizace) and the Union of Czechoslovak Youth (Svaz československé mládeže – SČM). Junák, the most important and largest organization of Czech and Slovak scouts, was taken over by Communist collaborators and dissolved in 1951.

A similar fate befell other scouting clubs and organizations, such as the gymnastic movement Sokol, the League of Czech Woodcrafters, and the YMCA. Scout leaders and older Boy Scouts were persecuted and subjected to lengthy imprisonments and judicial murders. They were described as members of counter-revolutionary imperialist organizations and potential fifth-column organizations. Some of them went into exile; others drastically limited their activities or managed to recreate undercover scout clubs illegally or under the guise of various sports and tourism clubs. After the regime solved the “problem” of scouting, its repressive forces also increased their pressure on tramping [Břečka 1999: 221-226].

The position of tramping was, however, different from that of organized sports and scouting – there was no central organization of tramps, and even various osadas or other communities were organized in an informal manner and based on personal friendships. Legalized weekend cabin colonies usually had some formal structure, and it was possible to destroy that organization, but much harder to destroy shared community places, as these colonies often consisted of private properties too small to be nationalized. The most common methods of persecution included various bans on communal activities, brutal police attacks on potlachs, roundups of tramps on railway stations, and everyday minor harassment, including random police patrol destruction of any items of clothing which looked too “American”.[Vinklát 2004: 56; Mácha 1967: 80-84; Kučerová 1997: 13-15].

It should be noted that there was a lack of commercially available clothing acceptable for tramping because of the general supply problems of the post-war economy, while many uniforms and army surplus items were readily available. Parts of American uniforms were especially sought after and became quite prevalent in Western Bohemia, the only region liberated by the Americans. Military clothing became increasingly popular with tramps because it was practical for outdoor activities, unobtrusive when worn in forests, and, if they were items of Western origin, included an aspect of symbolic passive resistance [Altman 2003:266]. Tramps also began to wear emblems with symbols of their Osada on their left sleeves; these emblems were called domovenka and were possibly inspired by military emblems or scouting badges (10). Such personal usage of symbols also reflected changes in tramping, as it was not easy to create new colonies of cabins, and there were many osadas that had no permanent legal, communal place and preferred to hike and use simple hidden campsites (campy). The number of tramps decreased, and a partial generation divide appeared for the first time – many older tramps reduced their activities and found inner exile in communal life in their cabin colonies. On the other hand, younger tramps, who were not very numerous, preferred hiking to sedentary camping and understood, and sometimes even proudly accepted, the role of pariah assigned to them by the communist regime. Tramping was still a kind of escapism and inner exile, not an official, fully-fledged resistance movement, but its antagonism to official structures was more pronounced [for comparison, see Kučerová 1997: 13-15: Noha 2007: 37].

The decline in tramping was reversed during the 1960s when the Communist regime was undergoing the slow liberalization that culminated in the events of the Prague Spring of 1968. The first positive mentions of tramping in the official press appeared in 1963, and the movement’s popularity among a new generation of young adults increased steadily [Vinklát 2004: 72-73; Kučerová 1997: 16-21; Petrová 2009: 61-63].

There were several reasons for this. More people joined the ranks of tramps because the level of persecution was lower, and thus the activity was more acceptable. At the same time, tramping still included aspects of disrespect for authority, informal friendship, and personal freedom. American culture remained popular with young people, and new Westerns, some filmed in the Eastern Bloc, were shown in cinemas. Traveling abroad became possible in the late 1960s, but it was still fraught with bureaucratic and economic obstacles. Thus the idea of tramping remained as a kind of game that allowed participants to create their own little romantic adventures, using the Czech landscape as a backdrop for the projection of their imagination.

The 1960s also introduced some other changes in tramping. While there was a strong and sometimes politically active left-wing in pre-war tramping, the actual Sovietization of Czechoslovak society and the stigmatization of tramps after 1948 proved to be a fatal blow for this leftist part of the movement. The social structure of tramps changed too. Many tramps of the 1920s and 1930s were members of the lower social classes: workers or apprentice craftsmen. By contrast, the society of the 1960s was more homogeneous, and tramping was no longer a predominantly blue-collar form of recreation [Kučerová 1997: 16-21]. The general consensus in post-war tramping was that the movement was apolitical, which actually constituted a political statement in its own right because it took place in a society where almost everything was expected to have a political dimension. Another reason for tramping being apolitical dates back to pre-war times and was based on the belief that tramps should be friends with each other. Heated political debates, it was felt, could quickly turn personal and thus did not belong at a campfire [see Hurikán 1990: 246-247; Waic and Kössl 1992: 48-49]. Communist control of the formal, totalitarian organization of all aspects of Czech and Slovak society and the permanent presence of political propaganda had only increased the need for escapist, egalitarian, and informal social space.

Post-war changes included the further evolution of tramp music, which had absorbed influences from American country music, bluegrass, and modern folk. This transformation had been taking place since the 1950s but culminated in the late 1960s with the appearance of a new and powerful generation of tramp musicians represented, among others, by the groups Greenhorns and Hoboes. New tramp music was more open to being intermingled with other genres, and song lyrics included not only the relatively simple sentimental, exotically-romantic, and humorous motifs found in earlier times but also more complicated symbolic, sarcastic, or earthy motifs, similar to those used by non-tramp modern folk singers and songwriters. This experimentation was sometimes criticized by older tramps who felt that earlier and now traditional tramp music was endangered and might disappear. But both old and modern songs coexist in the common tramp repertoire today [Vinklát 2004: 72; Mácha 1967].

Greenhorns Playlist – 180+ Videos / Songs

Liberalization ended abruptly with the Warsaw Pact invasion of 1968 and the beginning of political “normalization”. Scouting, renewed for a short time in 1968, was forbidden again and again continued under the guise of various other organizations [Břečka 1999: 239]. While undoubtedly totalitarian and able to use coercive violence, the regime was not as brutal as in the 1950s. The secret police were everywhere, and dissidents were persecuted, but almost nobody, including the more pragmatic Party members, actually believed in the victory of Communism, and the regime focused on preserving the status quo. This included allowing people to pursue their hobbies instead of participating in political life as long as these activities did not clash with the desired image of a socialist society and did not include potentially suspicious acts like traveling to Western countries or publishing uncensored texts or music. Many people from the cities turned to summer huts and former German cottages in the countryside and used them as second homes. This process led to an additional increase in recreational suburbanization near large cities, often at places where ramp cabin osadas, which had lost part of their historically simple character, had been located (11). The invasion of 1968 also initiated a wave of emigration; some of these emigrants were tramps, and they adhered to their lifestyle even in exile. There are still tramp ex-pat osadas in countries like the United States, Canada, and Australia.

The regime was antagonistic to tramping but did not attempt to destroy it completely as it had in the 1950s. Instead, it kept tramping under surveillance and practiced a certain level of police harassment while still permitting sanctioned pro-government organizations to run events such as music festivals featuring folk and country music and granting some space to tramps in the popular youth magazine Mladý svět (Young World). The most important music event sanctioned by the government was the competitive festival Porta, a massive non-political but politically supervised event. The Porta was popular with tramps, but not only with them, and introduced many genuine new musical talents, including young tramp musicians.[Vinklát 2004: 182-183]

Not all cultural activities related to tramping were official, however. Some were, and some were not. Many tramps were prolific amateur writers and poets, and their works were published in legal, semi-legal, and samizdat publications [Petrová 2009: 61-72]. The submissions to an influential contest for amateur tramp writers and poets named Trapsavec were established in 1971, then banned for political reasons, and then their publication was renewed in 1979. (consulted 26 June 2011)].

The themes of tramp poems and stories most often centered on poetic descriptions of nature and tales from the lives of tramps; they could also be related to tramp outdoor experiences in other ways. There was also a prominent element of the fantastic and of mystery fiction in these tales. Some of them included science fiction elements, often presented in a light-hearted manner, while others were based on contemporary legends popular among tramps. These were usually tales about ghosts and strange murders with motifs taken from campfire legends or related to legend tripping [for definitions, see Tucker 1999: 205-208].

The revolution of 1989 opened many new possibilities for Czech tramps, including freedom of speech and association. At the same time, the number of actual tramps dwindled noticeably over the course of the 1990s. (12) The reasons for this decline have not yet been analyzed, but there are probably three main factors.

The first one is freedom of movement combined with the affordability of foreign travel. Since 1989 it has been relatively easy to visit other countries, even exotic and distant ones, and there has been no need to find substitutes for such experiences by romanticizing the Czech landscape.

The second factor was tied to the increasing diversity of possibilities for self-realization. Under the Communist regime, there had been lots of free time because there was a lack of emphasis on effectiveness in many jobs. Simultaneously, recreational possibilities were limited, and the system made it difficult for talented hobbyists or people with organizational skills to stand independently and turn their hobbies into professions. This was reversed after the Velvet Revolution – there were suddenly many more possibilities of self-realization in occupational and recreational activities. This was combined with an increasing emphasis on effectiveness on the job and work productivity. These factors negatively affected the amount of leisure time that most people, especially minor entrepreneurs, who have started their own businesses, could enjoy.

The third factor is generational and related to the role of tramping as a passively anti-establishment subculture with ties to the “second culture” of the more politically active underground. Tramps, with their escapist mentality and emphasis on freedom and friendship, can be considered to be a part of the “inner exile” movement, communities located in the grey zone between the social world of the communist party and the underground of dissenters.

After the revolution, however, the need for such lifestyles was lost. Most young people did not feel the need to participate in such mild and passive anti-establishment activities, and competition from other subcultures and movements of possible anti-establishment or generational significance increased. The youth of the 1990s and 2000s were also more interested in participating in specialized out-of-school activities that were more profitable than scout-like clubs based on universal education. And there were fewer young people with outdoor skills and inclinations toward spending their free time out in nature – which meant that there were also fewer potential tramps.

It is, however, interesting that while tramps are not the subject of political persecution in today’s Czech Republic and Slovakia, tramping itself as an outdoor activity still remains on the brink of legality because of the manner in which it utilizes the landscape [Altman 2003: 260]. Czech forests, and the landscape in general, are free access areas according to law. This applies to privately owned forests as well as public land, although access may be limited for justifiable reasons such as game-keeping, the protection of property from vandalism, military training, and, most significantly, the protection of nature. Camping in forests without a permit, and especially making campfires, is illegal in most cases for safety reasons. This leads to a conflict of interests between tramps, with their disrespect for authority, and state agencies for the protection of nature and wildlife. Such conflicts became most apparent in sandstone areas such as the so-called Bohemian-Saxon Switzerland or Bohemian Paradise. These were popular with Czech tramps who built their camps under sandstone abris. The management of these areas, which were often archaeological sites dating back to the Mesolithic era, attempted to restore them to as nearly a natural state as possible and tried actively to locate and fine groups of tramps. The management was in turn, attacked by tramps for an indiscriminate and excessively severe approach [Jenč and Peša: 2006: www.ontheroads.net;

www.roverky.cz (consulted 26 June 2011)]. Such conflicts of interests sometimes problematize relations between tramping and environmental movements in general – even though both groups are claiming to be nature-friendly and had occasionally cooperated in the past when both were members of the “grey zone” of Communist Czechoslovakia [Petrová 2009: 77-78].

Tramping in 2010 is certainly different from the tramping of the first “wild scouts,” but the difference has been achieved more by accretion than by replacement. There is a generational difference between younger tramps, who tend to prefer hiking and simplicity, and older ones, who are focused on weekend communal life in cabin colonies. However, these are not two separate groups but two sides of one continuum. Both old pre-World War II and modern tramp songs are played by campfires, and large potlachs are usually attended by all generations. There is also a difference in clothing: younger tramps prefer either simple clothing in natural colors or parts of military uniform (13), while decorative cowboy-like and western-styled clothing is more often seen among members of the older generation.

Defining tramping today as a single unit may be problematic, as it is both a way of spending time outdoors and also a lifestyle. The movement has its core of traditionalists and lifestyle tramps, but there is no formal divide between these and the fringe represented by occasional campers or people who have some of the attributes of tramps but do not consider themselves to be members of the movement. The attributes in question include wearing tramp-like clothing, adhering to the unwritten ethical code of tramping (which includes friendship even with unknown tramps and respect for nature), spending leisure time in a tramp-like manner (camping and hiking), respecting the traditions of the movement and following tramp customs (e.g. using a special handshake, greeting others with the word ahoj (14), addressing all other tramps as kamarád and using special tramp nicknames for friends (15)), being a member of an osada, considering oneself to be a tramp, and being considered a tramp by other tramps.

Tramping has left a deep mark on Czech culture over the hundred years of its history. It has been one of the preferred forms of recreation and socializing for several generations of young people, especially in the 1920s-1930s and the 1960s-1980s. The tramp lifestyle has contributed to the general popularity of tramp music and related genres such as folk and country (16). Tramp songs are often played by campfires, even by non-tramps, and constitute a large part of the folk repertoire. Tramping has also influenced the character of the suburban landscape and recreational architecture because tramp osadas function as a nucleus and inspiration for other recreational colonies. Various artifacts produced by members of the movement, such as carved totems, invitation cards (video), diaries (cancák), small clothing accessories, communal event memorabilia, and others, can be considered to be a part of modern folk art. The subculture also has its own legends, traditions, and slang.

From a social scientist’s point of view, tramping, because it originated as an offshoot of scouting and a unique reflection of the romantic image of America in Czech society, also represents a much bigger and multi-faceted social phenomenon. It is an unorganized, open-ended, self-sustaining movement that can be considered to be both a precursor to post-WW2 youth movements such as the Hippies or the rock subculture – and also a distinct alternative to them.

Tramping bears characteristics that allow it to be labeled as a youth subculture from a sociological point of view. It was and still is usually adopted in the late teenage years, a liminal period in which the constraints placed on social behavior are challenged and independence from the family is sought. It leads to the creation of distinct communities which offer belonging and status. It also has a dimension of collective rebellion directed against mainstream society. This countercultural aspect is relatively mild in the case of tramping but ever-present and part of the movement’s moral code. The movement’s distinctive identity is supported by its symbols in material culture, art, and folklore [for details on youth subcultures, see Hodkinson 2007: 2-5 and following].

The history of tramping also provides a unique insight into a youth-subcultural movement whose evolution was partially rebooted by outside influences. The tramping of the first half of the 20th century began as the hobby of a few and a fringe offshoot of a respected scouting movement. It then gained mass popularity during the 1920s as a prominent youth subculture with countercultural aspects and was heading for absorption by mainstream culture in the 1930s. These development stages seem typical for many youth-subcultural movements of the 20th century, but this was probably the first modern and large-scale youth subculture to be born and experienced in Bohemia. A possible local precursor, the romantic movement of the 19th century, was influential but more an expression of generational protest than an attempt to create an independent social space. As it turns out, tramping was not allowed to be completely absorbed (or exploited) by the mainstream culture. The Communist regime pushed it back into the grey zone and, through attempts to tame it, paradoxically boosted its aspects. By then, however, the movement was already deeply rooted in Czech society, and mainstream culture embraced tramp motifs whenever it was politically possible. This development of acceptance, which took place in the late 1960s and also in the 1980s-1990s, in some ways mirrored the original evolutionary stages of the movement.

Tramping has been repeatedly described as a unique phenomenon in the previous paragraphs. The aforementioned primacy of tramping as a modern Czech youth-subcultural movement is only one of the reasons for making such a statement. Another reason lies in the fact that it has always been limited to Czech and Slovak populations: all known tramp osadas in other countries are formed by ex-pats, and while the word “tramping” is still used in English to describe various hiking activities, the meaning is different. It is, therefore, advisable to use the term “Czech tramping” or something similar in cases of possible confusion.

Czech tramping, while not officially connected with a specific nationality, was not adopted by many members of other groups, the large German minority of pre-war Czechoslovakia included. A similar movement of slightly different origin, the Wandervogel, was more popular among Germans. Wandervogel was (and still is) a youth romantic hiking scoutlike movement officially founded in 1901. It differs from tramping in terms of its slightly higher level of organization and the fact that is draws its inspiration from German mythology and history rather than from the American Wild West. [http://www.wandervogel.de/ (consulted 26 June 2011)] There is no mention of tramping bearing any relationship to the Wandervogel. Rather, it is more likely that both movements sprung up independently and grew to fill similar niches. There were friendly contacts between representatives of the two groups, but these were more accidental than frequent [Vinklát 2004: 8-9].

The relationship between tramps and Czech scout-like organizations was often verbally antagonistic, at least on the official level, as there was competition between them; at the same time contacts on the personal level were far less tense. There were many people who were active in both, especially when the communist regime banned scouting. In such times, the “them” of the “us versus them” divide were the Communists. Totalitarian regimes also indirectly forced banned Boy Scout clubs and similar organizations to create proxy clubs under a “false flag,” and if such clubs were also banned, their leaders and older members often continued their activities as tramps, at least for a while. This blurred the borders between the different movements and eased the transmission of customs, songs, symbolism, and people between them [Makásek 2004: 5- 6; Krško 2008: 62-69]. For example, the typical tramp handshake is now often also used by cavers, rock climbers, young tourists, folk musicians, and others. Western reenactment and living history of Euro-Indian groups also became part of this milieu around the 1970s [http://indiancorral.cz/cz/index.php?p=3 (consulted 26 June 2011)]. But whilst there certainly were personal connections between them and tramping and attempts to recreate Native American customs in a realistic way had already existed previously (especially among woodcrafters), their focus was often different. Tramping stresses hiking and communal activities with friends and does not favor the introduction of many rules. Their dress code is forever under discussion, but a tramp’s clothing does not need to be realistic. Tramps of today usually do not go outdoors to imagine that they are cowboys, as they more often did in the 1920s and 1930s. The movement has stabilized; it has a long tradition and most tramps leave their homes on weekends simply to be tramps. (17)

Notes

- The word tramping was introduced into the Czech language from English as a description of an activity – similar to the introduction of camping or, more recently, bungee-jumping. Its meaning has shifted from the original English and is used solely for describing the subculture in question or the behavior of its participants. Other transcriptions include trempink or trampink. Tramping as an activity may be called trampování or trempování; a participant in the activity is a tramp or tremp. This variance does not indicate a difference in meaning of the word; it just represents different attempts to resolve conflicts between Czech and English pronunciation.[Pergelová 2004: 30-31]

- For example the Catholic gymnastic movement Orel or the social-democratic Dělnické tělovýchovné jednoty (Workmen’s Gymnastic Unions).[Břečka 1999: 12]

- Popular authors included J. F. Cooper, J. O. Curwood, Z. Grey, B. Hart, J. London and E. T. Seton. One of the most popular early movies was the 1917 American serial Bull’s Eye directed by J. W. Horne featuring Eddie Polo. [Waic and Kössl 1992: 13; http://www.imdb.com/title/tt0008935/ (consulted 26 June 2011)]

- “Aničkas, Máničkas and Boženkas became Annies, Maries, Bobinas or Daisies, Betsies and Virginies overnight; it was even worse concerning boys. Jarda became Harry, Pepík became Bob, Ota turned into Brandy, Zdeněk into Iron Fist or Wintrop, Edie and sometimes even Swenny, Grizly, Káča, Říman, Bill, Old Saterhand (sic), Farnum, Dawson, Jack etc. etc. (…) There were never so many sheriffs in the world as in Bohemia in 1919-1920. There was not a group without a sheriff, not even a couple without a sheriff.” [Hurikán 1990: 16-17]

- The haversack, of all pieces of camping equipment used by tramps, probably has the most slang terms attached to it. Most of them are derived from the term US torna (U.S.backpack) – usárna, úeska, uzda, usařina or usranec (the last one being a word play on US ranec – a US pack – and usranec – a slang neologism which also refers to a piece of excrement or a “shitty” person) or its shape – hadraplán (a rag plane), špekbuřt (a speckwurst) or mrtvý dítě (dead child). The style of packing a haversack is considered to reflect the personality and skills of its owner.[http://www.ontheroads.net/rubrics/tramping/batoh_uska/uska.php (consulted 26 June 2011)]

- The Name of an osada was often preceded by the abbreviation T.O. (standing for trampská osada). Other letters were sometimes added to emphasize the place of origin of the osada or its other characteristics – for example T.O.P. could mean trampská osada pražská (a tramp osada from Prague). Some examples of characteristic names of various tramp osadas and camps follow: Ztracená naděje (Lost Hope, 1918), Měsíční údolí (Moon Valley, 1922), El Paso (1927), Fort Adamson (1930), Grey Grizzly (1931), Askalona (Ashkelon, 1933), Pistolníci (Pistolleros, 1944), Zlatý klíč (Golden Key, 1956), Mimo zákon (Out of the law, 1963), Cabaléro (Caballero, 1966), Mississippi (1967), Mývalové (Racoons, 1976), Ministerstvo vnitra (Ministry of the Interior, 1979), The Thirten Stars (sic, 1986), Zlatokopové (Gold Diggers, 1987), Kamarádi dlouhých cest (Friends of Long Journeys, 1988), Galadriel (1994), Pod Psí skálou (Under the Dog Rock, 2002), Krakonošovo Quantanamo (Rübezahl’s Guantanamo, 2008). Selected from an extensive list in [Moidl and Moidlová 2010: 136-163].

- The most common terms used for tramp trips were vandr (from Czech version of German wandern – to wander, to hike) and čundr (from German tschundern – to wander, to walk in a sliding manner) [Pergelová 2004: 31, 25].

- Some popular early composers and performers of traditional tramp music were Jenda Korda, Pedro Mucha, Jarka Mottl, Eda Fořt, Géza Včelička and Eduard Ingriš.[Hurikán 1990: 201-210; Mácha 1967]

- There is a word in tramp slang that describes a non-tramp in a pejorative manner – paďour. The word is etymologically unclear, but probably related to the word padavka (weakling) or the word djaur – a non-Muslim person – which was taken from the adventure novels of Karl May and other authors and used by tramps as ďaur – a playful, non-serious invective. Thus pa-ďour acquires the meaning of “false or imperfect djaur” – a double invective. The process of tramping or of individual tramps losing their edge was called zpaďouření (a process of turning into a paďour). A term used for a passively malevolent nontramp is mastňák (greaser), stereotypically a fat, sweaty bourgeois-like person leaving waste in the forest, especially greasy papers left after a picnic. [Waic – Kössl 1992: 64-65; Pergelová 2004: 28]

- An extensive online collection of domovenkas, flags of tramp osadas and other related art may be seen at: [http://picasaweb.google.com/nastramp (consulted 26 June 2011)].

- [Zapletalová 2007] offers an overview of the Czech summerhouse phenomenon; discussion of its relation to tramping appears on pages 24-25.

- There are almost no estimates of the total number of tramps during different historical periods, including the present. Researchers studying tramps often base their comparisons on the numbers of tramps at the most popular suburban passenger train lines. According to them, there was usually at least one wagon full of tramps on weekends for each day train during the 1920s, 1930s, 1970s and 1980s. Today, the number is just 10 tramps on such a train. [personal opinion: P. Borský, Jílové u Prahy, 2010]

- The wearing of these uniform components is usually motivated by tradition, their suitability for outdoor activities, simplicity, and unobtrusiveness in nature. Since the 1990s there are also some groups of tramps who consider themselves to be fans of military history. They wear real uniforms (usually post-WW2 American ones) and combine their trips with activities such as airsoft games or survival training. Such “war games”, while taken quite seriously during the course of play, still retain their recreational character and are not necessarily linked to political extremism. [Krško 2008: 102; Moidl and Moidlová 2010: 13-16]

- The word ahoj! probably originates from the English sailor’s greeting a hoy! [Pergelová 2004: 24], it was extensively used by canoeists and tramps and later entered mainstream Czech language, where it is used as a common informal greeting.

- The nicknames of tramps are most often Americanized versions of their given names (Marie = Mary), word-plays on their names (Rudolf = Rudan), animal names or attempts to characterize the tramp metaphorically or by a typical feature of their body or behavior [Pergelová 2004: 18-19].

- Examples of both old and contemporary tramp music may be found on many Czech internet sites. Searches for keywords “Ryvola” and “Hoboes”, “Greenhorns” and “Vyčítal”, “F. T. Prim”, “Nedvědi” or “Wabi Daněk” on YouTube usually offer representative examples of modern tramp music sung by professionals and advanced amateurs. Older songs dating to 1920-1930 are less well represented on the internet, but searches for “stará trampská píseň” or “Vlajka vzhůru letí” on YouTube also yield some results. Texts with chord markings for guitar may be found at [http://www.zpevnik.wz.cz/?id_a=82 (consulted 26 June 2011)] for example. A Facebook group dedicated to tramp songs up to the 1970s also exists and many examples, both recordings and movies from recent live plays, are posted there: [http://www.facebook.com/group.php?gid=87010509354 (consulted 26 June 2011)]

- A collection of photographs of modern tramps may be seen for example at Jan Moravec’s online gallery: [http://www.etf.cuni.cz/~moravec/fotky/ind-tr.html (consulted 26 June 2011)

Bibliography

Altman, K. 2003: “…jak někteří trampují” […how do some of them tramp], in Rajče na útěku. Kapitoly o kultuře a folkloru dnešních dětí a mládeže s ukázkami [Tomato on run. Chapters about culture and folklore of today’s children and youth with examples], J. Pospíšilová, (ed.) Brno: Doplněk.

Břečka, B. 1999. Kronika čs. skautského hnutí [Chronicle of Czechoslovak scouting movement]. Brno: Brněnská rada Junáka.

Hodkinson, P. 2007. “Youth cultures: A critical outline of key debates,” in Youth cultures. Scenes, Subcultures and Tribes. Hodkinson, P. and W. Deicke, (eds.). New York – London: Routledge.

Hurikán, B. [pseud. of Peterka, J.] 1990. Dějiny trampingu [History of tramping]. Praha: Novinář.

Jenč, P. and V. Peša. 2006. “Projekt Obnova skalních dutin stavu přírodě blízkému v CHKO Český ráj” [Project “Renewal of rock cavities into a state close to nature”] in Pískovcový fenomén Českého ráje [Sandstone phenomenon of Bohemian Paradise] Jenč, P. and L. Šoltysová (eds). Turnov: ZO ČSOP Křižánky 41-50. .

Krško, J. 2008. Meziválečný tramping na Rakovnicku [Interwar tramping at the Rakovník region]. Rakovník: State provincial archive at Prague – State provincial archive at Rakovník.

Kučerová, B. 1997. Tramping po roce 1945 [Tramping after 1945]. Diploma thesis. Charles University – Faculty of gymnastic education and sports: Praha.

Makásek, I. H. 2004: Kluci z Neskenonu. Cesta ekumenického skautingu [Boys from Neskenon. Path of ecumenical scouting.] Nika: Praha.

Mácha, Z. ed. 1967: Kronika trampské písničky [Chronicle of tramp song]. Praha: Bonton.

Moidl, Z. and O. Moidlová. 2010. Sbírka trampských domovenek a jiných atributů [Collection of tramp sleeve patches and other attributes]. Liberec: ROSA.

Noha, R. 2007. Odlesky táborových ohňů [Reflections of campfires]. Jílové u Prahy: Regional museum at Jílové u Prahy

Pergelová, K. 2004. Trampský slang ve slovanském kontextu [Tramp slang in Slavonic context]. Intermediate term thesis. Prague: Charles University – Department of Slavonic and Eastern European Studies. Also available at: teketapa.sweb.cz/Slang_-_Klara.doc

Petrová, J. 2009. Zapomenutá generace osmdesátých let 20. století. Nezávislé aktivity a samizdat na Plzeňsku [Forgotten generation of the eighties. Independent activities and samizdat at Plzeň region]. Plzen: Jana Petrová.

Rottman, G. and R. Volstad. 1989. US Army Combat Equipments 1910-1988. London: Osprey Publishing.

Tucker, E. 1999. “Tales and legends”. in Children’s Folklore – A Source Book. B. Sutton-Smith, J. Mechling, T. V. Johnson and F. R. McMahon (eds.). Logan: Routledge, 193-211

Vinklát, P. D. 2004. Kronika trampingu v Jizerských horách. 1934-2004 [Chronicle of tramping at Jizera Mountains 1934-2004]. Liberec: Knihy, 555.

Waic, M. and J. Kössl. 1992: Český tramping 1918-1945 [Czech tramping 1918-1945]. Praha: Práh, Liberec: Ruch.

Web Pages

The following were all consulted on June 26, 2011. (We have removed the ones which are no longer active.)

- Bull’s Eye (1917).

- Der Wandervogel

- Domov trampů v zahraničí

- Indian Corral. Indian Hobby in the Czech Republic

- Klasické trampské písně – zpěvník s akordy [Classical tramp songs – a

- songbook with chords]

- On the Roads – Diskuze – Tramping vs ochrana přírdy, ubývání “divočiny”, … [On the Roads – Discussion – Tramping vs. protection of natre (sic!), diminution of “wilderness”.

- Sdružení Avalon – Trapsavec [Avalon Association – Trapsavec]

- Zakládací listina nezávislé občanské iniciativy Roverští patrioti [Foundation charter of independent civic initiative Patriots of Roverrocks].

Guest Post Author

Jan Pohunek

Jan Pohunek currently works at the Department of Ethnography, National Museum, Prague, Czech Republic. Jan does research in Archaeology, Historical Anthropology and Cultural Anthropology. His skills and expertise include Folklore, Ethnography, and Social and Cultural Anthropology.

See his profile and read some of his other works at Academia.edu.

We tirelessly gather and curate valuable information that could take you hours, days, or even months to find elsewhere. Our mission is to simplify your access to the best of our heritage. If you appreciate our efforts, please consider donating to support this site’s operational costs.

See My Exclusive Content and Follow Me on Patreon

You can also send cash, checks, money orders, or support by buying Kytka’s books.

Your contribution sustains us and allows us to continue sharing our rich cultural heritage.

Remember, your donations are our lifeline.

If you haven’t already, subscribe to TresBohemes.com below to receive our newsletter directly in your inbox and never miss out.

I simply wanted to compose a brief message in order to express gratitude to you for the remarkable advice you are placing on this site. My time-consuming internet lookup has at the end of the day been recognized with brilliant concept to share with my great friends. I’d repeat that we visitors are unequivocally endowed to live in a wonderful place with so many brilliant people with very helpful suggestions. I feel really fortunate to have discovered your website page and look forward to some more excellent times reading here. Thanks once again for your amazing work, dedication, writing, and passion for everything Czech.

This has been my life with my Czech friends.

My dad took me with him to many potlachs. When I was younger, it was fun to get lost in the woods. When I got older, I took girlfriends and we had fun skinny dipping in the river. In the evenings, everyone was drunk by the bonfire singing songs and being happy together. My father is not gone, and I seek out the last few older Czechs who still keep up this tradition. I’m sure I’ve seen you at a potlach, Kytka.

I now have a much better understanding of my Czech friends love for signing and playing guitar by a campfire with a sausage roasting on a stick.

Very cool.