A Poem on the Anniversary of the Velvet Revolution

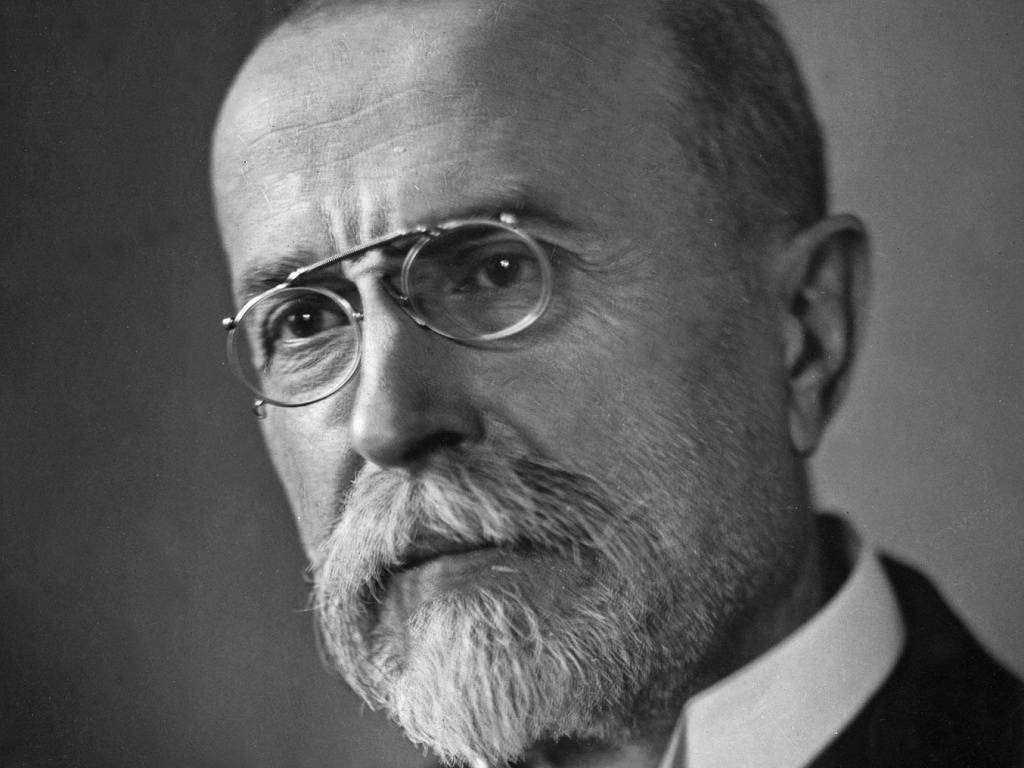

Dear readers, on the occasion of the 31st anniversary of the Velvet Revolution, we are bringing the poem A Prayer by a Czech author living in Australia, Professor Josef Tomáš. With the poem A Prayer, the author expressed his feelings of how he, at the end of 1989, perceived an incredible event, the end of communism in his homeland.

The work illustrates the dark background of socialism, the arrest of his comrades and the persecution by the StB and the then regime, which Professor Tomáš experienced.

“One day in August, I went to my scout friend Jirka. I rang the bell at the gate of the house when his mother appeared in the window, waving desperately, asking me to walk away. Later I found out how lucky I was, because at that moment StB was in the house arresting Jirka. I didn’t see him until two years later on two visits, as I am describing in the poem. And five years later, when he received clemency from President Novotny. He then spent some time in a sanatorium in the Highlands, because he had a lung breakdown. Then followed 21 years of separations, when I emigrated. After 1989, I met him several times, he worked as a laborer and was eventually murdered,” says Professor Josef Tomáš.

A PRAYER

Yes – blessed art thou among lands! –

And yet – alone – of your free will –

never would you have managed

to free yourself from the iron grip

of that all-consuming evil,

because we, your fruit, your people,

have only ever been half-blessed…

Like the wick of an oil lamp, at one end

– soaked through with the fear of extinction –

we are heavy, thick and reeking,

and on the other? – there, only rarely,

we burn with an exquisite light,

our unexpected ignition

surprises us most of all!

What are we anyway? –

Whether light or heavy, always shallow

In our feet and heads rarely at home

Forever flitting between two poles

Often sinking into deep stupor

Not finding anywhere a fourth dimension…

You, our country,

so many times devastated,

more than half depopulated,

starved of your own speech …

How do you muster that miracle power

that lifts you out of humiliation?

Now at last you can stop your wailing,

you, with your heads filled with gloom.

Were we not promised

that a few righteous ones would suffice

to save the whole universe?

– and we just one small country!

You, room, flooded with white light

They are praying, they are singing

Mostly simply existing

But turning their gaze in quite different directions

To the usual ways of writing and speaking

Oh you, a time which let women until recently Christian

march in the streets of Czech cities, only now with red scarves,

and let unwashed workers play at soldiers,

and bought the peasants for thirty pieces of silver,

and out of loudspeakers declared several grave sins

– envy, hatred, pride – to be the highest virtues;

and then, a few years later, I saw marching at Wilson Station

the evicted farmer, now convict-soldier František Šeda,

rifle-less, black epaulettes and bloody calluses,

and saw how the borderline of the Russian occupation

ran through a hastily-built barracks at Dolní Žďár,

halfway between Ostrov nad Ohří and Jáchymov,

(imagine, a piece of my homeland, on which I was strictly forbidden

to step, and when I did so anyway, just for a few meters,

a miserable Czech informant immediately made sure

that I was led under Czech submachine gun to the police station

and investigated there for many long hours – by a Czech!),

and from that forbidden side, from uranium Equality and Unity

and uranium Brotherhood, Czech convicts were brought

to the barracks for visits, among them my twenty-year-old friend

Jirka Mráz, sentenced to fifteen years in the mines,

riding in pickups in the biting frost of January,

in closed buses in the stifling summer –

expert architects of such a vicious pigsty,

those halfwit Czech-Communist screws –

I am a witness to it all, I went there twice,

in the same year that in the Marxist library

I felt evil’s hypnotic presence – the protoplasm of evil – on my skin:

it stared at me from the monstrous grey

of the Marxist-Leninist pseudo-teaching manuals…

Perhaps because of all that, and much more,

I, still young, knew where evil dwelled;

where and how it entered unguarded Czech heads,

and then, with their help, flooded the hundred-towered city –

Towers of empty temples – hands unfolded

Windows of crumbling houses – living emptied

Hands of abortion doctors – lives annihilated

Eyes of frightened parents – respect eradicated

Words of corrupt teachers – young minds violated

Speeches of treacherous leaders – crimes uncastigated

and finally the whole Czech land –

Ploughed meadows – you, the dead beetles

Shrivelled fields – you, the dead soil

Poisoned forests – you, the dead birds

Polluted rivers – you, the dead fish

Crumbling barns – you, the dead cattle

Deafened dwellings – you, the dead love

So tell me, how did you manage to free yourself

from that host of omnivorous evils? –

Where did that other power come from,

at first betrayed by us and soon after suppressed by Him –

that power of good? – Those few students perhaps? –

Those few, just briefly righteous,

but cynical once again soon after? …

Oh no, no! That power must be from somewhere else!

Only their mothers’ love could it have been –

or, more likely, their mothers’ fear:

“They beat our children! They beat our children!” …

But in fact, it was you,

you, the Earth, our Earth!

You who are incarnate in mothers! –

Yes, none but you,

you good, great, mighty Earth!

Was not your colour always

the colour of all great mothers:

the mothers of Krishna, of Buddha, of Christ?

You, blue-white, embodied in all mothers!

We had to fly as far as the Moon,

to finally see you as you are:

Blue-white hovering

In unimaginable loneliness

Through the ultra-black emptiness

Of the boundless universe

Now we finally understand those emotionalists,

to whom you have appeared since time immemorial;

always as a celestial queen,

always above your fountain of water,

and with your wall of rock behind you…

Like a blue-white celestial queen –

Tower of ivory,

House of gold,

Ark of the Covenant,

Gate of Heaven,

with tears in your eyes warning of destruction,

urging us to repentance, to redemption!

Oh, stay with us! Don’t leave us!

– ora pro nobis peccatoribus et nunc et in hora mortis nostris

And they continue to pray…

In a room flooded with white light…

Turning their gaze in a quite different direction…

OM MANI PADME HUM

(And in Czech…)

Modlitba

Báseň k výročí Sametové revoluce

Vážení čtenáři, k příležitosti 31 let od Sametové revoluce přinášíme báseň Modlitba od českého autora žijícího v Austrálii, pana profesora Josefa Tomáše. Básní Modlitba vyjádřil autor své pocity, jak závěrem roku 1989 vnímal neuvěřitelnou událost, konec komunismu v rodné vlasti. Dílo ilustruje temné pozadí socialismu, zatýkání jeho kamarádů a perzekuci ze strany StB i tehdejšího režimu, které profesor Tomáš zažil.

„Jednoho srpnového dne jsem šel ke svému skautskému kamarádovi Jirkovi. Zazvonil jsem u branky domu, když v okně se objevila jeho matka a zoufale mávala rukou, abych šel pryč. Později jsem se dozvěděl, jaké jsem měl štěstí, neboť v té chvíli bylo zrovna v domě StB a zatýkalo Jirku. Viděl jsem ho pak až za dva roky při návštěvě, jak to popisuji v básni. A později až za 5 let, když dostal milost od Prezidenta Novotného. Strávil pak nějaký čas v sanatoriu na Vysočině, protože měl rozpad plic. Pak následovalo 21 let odloučení, když jsem emigroval. Po roce 1989 jsem se s ním několikrát sešel, pracoval jako dělník a nakonec ho zavraždili,“ vypráví profesor Josef Tomáš.

MODLITBA

Vskutku — požehnaná jsi mezi zeměmi! —

Přesto však — sama — ze své vůle jen —

bys nebyla nikdy dokázala

vyprostit se z ocelového sevření

onoho všezachvacujícího zla,

protože my, tvůj plod, tvoji lidé,

jsme odjakživa sotva napůl požehnaní …

Jako knot lampy jsme: na jedné straně

— nasáklí strachem z nepřežití —

jsme těžcí, hustí, páchnoucí,

a na té druhé? — tam jenom zřídka kdy

zazáříme intenzivním světlem,

sami pak nejvíc překvapeni

tím nečekaně náhlým vzplanutím!

Co jsme to vlastně? —

Ať lehcí či těžcí vždy jen dvojrozměrní

V nohách i v hlavě málokdy přítomní

Mezi dvěma póly věčně kmitající

V hloubku otupění často upadající

Čtvrtý rozměr světa stále nenacházející …

Ty naše země!

Tolikrát už jsi byla zpustošená,

více než zpola vylidněná,

své vlastní řeči pozbavená …

Odkud bereš onu zázračnou sílu

na pozvednutí se ze svých ponížení?! …

Přestaňte konečně naříkat,

vy věčně zachmuření!

Nebylo nám snad přislíbeno,

že pár spravedlivých postačí

k záchraně celého vesmíru?

— natož pak jedné malé země!

Pokoji bílým světlem zalitý!

Oni se modlí oni zpívají

Oni většinu času jen tak prostě jsou

Ale docela jiným směrem zahleděni

Než jak se píše nebo mluví nahlas

Ó ty dobo, kterás dovolila ženám ještě nedávno křesťanským

pochodovat ulicemi českých měst, teď však s rudými šátky,

a povolilas nemytým dělníkům, aby si hráli na vojáky ve zbrani,

a katolické rolníky sis koupila za třicet stříbrných panských polí,

a z ampliónů jsi prohlásila několik hlavních hříchů

— závist, nenávist, pýchu — za nejvyšší ctnosti,

a kdy o pár let později jsem zahlédl u Wilsonova nádraží

pochodovat vojína Františka Šedu beze zbraně,

zato ale s černými výložkami a krvavými mozoly,

a viděl jsem též, jak narychlo sbitým barákem v Dolním Žďáru,

napůl cesty mezi Ostrovem nad Ohří a Jáchymovem,

procházela hraniční čára Rusáky zabraného území

(představ si to, kus mé vlasti, a já měl přísně zakázáno

tam nohou vkročit, a když jsem to na pár metrech ignoroval,

malý český člověk-udavač se ihned udýchaně postaral o to,

abych byl odveden pod českým samopalem na strážnici

a několik dlouhých hodin tam byl vyšetřován — Čechem!),

a z té zakázané strany do toho baráku sváželi k návštěvě

z uranové Rovnosti a Svornosti, a z uranového Bratrství,

české trestance-mukly, a mezi nimi mého dvacetiletého

na patnáct let odsouzeného kamaráda Jirku Mráze,

a to za třeskutě mrazivého ledna na otevřeném náklaďáku

a v dusném horkém létě v uzavřeném autobuse —

na to měli, na takovou zlomyslnou sviňárnu,

ty vymiškované mozky komunisticko-českých bachařů —

já jsem toho svědek, já tam dvakrát byl,

a to bylo ve stejném roce, kdy jsem v ulici Celetné

fyzicky pocítil hypnotickou přítomnost zla — protoplazmu zla:

uhrančivě na mě zírala ze zrůdně šedivé barvy

příruček marxisticko-leninského pseudo-učení …

Pro toto všechno snad, a ještě pro mnohem mnohem víc,

jsem už za mlada dokázal rozpoznat, kde zlo přebývá,

a kudy a jak vstupuje do strachem připravených českých hlav,

aby pak s jejich pomocí zaplavilo nejprve stověžaté město —

Věže prázdných chrámů — ruce nesepjaté

Okna zanedbaných domů — žití prázdné

Ruce potratných lékařů — životy zabité

Oči ustrašených rodičů — úcto uprchlá

Slova prodejných učitelů — mysli znásilněná

Projevy zrádných vůdců — činy zločinné

a z něho nakonec i celou českou zem —

Louky zaorané — vy broučci mrtví

Pole poprášená — ty půdo mrtvá

Lesy otrávené — vy ptáčci mrtví

Řeky znečištěné — vy ryby mrtvé

Chlévy zanedbané — vy dobytčata mrtvá

Obydlí ohlušená — ty lásko mrtvá

Prozraď mi tedy, jak ses dokázala osvobodit

od tolikerého všezničujícího zla? —

Odkud se v tobě vzala ta druhá síla,

ta nejprve námi zrazená a brzy nato jím potlačená

síla dobra? — že by těch několik studentů? —

Těch pár, jen na krátký čas spravedlivých,

zanedlouho však opět malověrně cynických? …

Ó ne, ne! Ta síla musela přijít zcela odjinud!

Jedině láska jejich matek to mohla být —

anebo, ještě spíše, ta obava matek:

„Bijí naše děti! Bijí naše děti!“…

Ale to jsi potom byla vlastně ty,

ty Země, naše Země!

Ty, která se přece ztělesňuješ v matkách! —

Ano, nic jiného nežli ty,

ty dobrá, veliká, mohutná Země!

Tvá barva byla přece

barvou všech velkých matek:

matky Kršny, matky Buddhy, matky Krista.

Ty modrobílá, vtělená do všech matek!

Museli jsme odletět až na měsíc,

abychom tě konečně mohli takto spatřit:

Vznášení modrobílé

V osamělosti nepředstavitelné

Prázdnotou černočernou

Vesmíru neohraničeného

Nyní konečně rozumíme těm několika citlivcům,

kterým ses tady už odedávna zjevovala;

a pokaždé jako nebeská královna,

a vždy nad pramenem své vody,

a se stěnou své skály za sebou …

Jako modrobílá nebeská královna —

Věži ze slonové kosti

Archo úmluvy

Bráno nebeská

Dome zlatý —

se slzami v očích varující nás před zkázou,

nabádající nás k pokání, k polepšení!

Ó zůstaň s námi! Neopouštěj nás!

— ora pro nobis pecatoribus et nunc et in hora mortis nostris

A oni se nadále modlí …

V pokoji zalitém bílým světlem …

Docela jiným směrem zahledění …

OM MANI PADME HUM

Notes:

The line when murderers were hanged by murderers alludes to events in Czechoslovakia after the Communist coup of February 1948, which was followed by a series of public and secret trials. Between 1948 and 1956, a total of 244 people were executed on political charges and a further 8,500 died as a result of torture or in prison. At least 100,000 people were imprisoned for acts against the Communist state. In 1950, there were 422 concentration camps in Czechoslovakia in which prisoners were held under gruesome conditions. That year, the number of prisoners in such camps amounted to 32,638 men and women.

The line the cruellest of years, nineteen fifty-two refers to the show trial in Prague during November 1952, whose main accused was Rudolf Slansky, first secretary of the Czechoslovakian Communist Party. Slansky and eleven other high-ranking party officials were sentenced to death.

(Sources: Adapted from Communist Crimes and The Return of Agnes of Bohemia.)

The Velvet Revolution Monument

Nine bronze hands protruding from a wall honor the student uprising that led to the fall of Czechoslovakia’s Communist government. The plaque acts as a memorial to the non-violent student uprising of 1989 that led to the downfall of Communism in what was then known as Czechoslovakia. The outstretched hands, their fingers splayed in a “V” for victory, represent the students who faced off against riot police, sparking a series of protests against the government. The students were commemorating the 50th anniversary of when the Nazis stormed Prague in 1939. On that occasion, students were attacked by police as well.

Today, people honor the students and their fellow dissidents by leaving candles, wreaths, and ribbons at the memorial. If you visit around November 17th, the day the uprising began, you will possibly get to see the memorial when the hands are holding lit candles, the fingers dripping with melted wax. The plaque is no longer in its original location—it’s said it had to be moved because all the items tied or placed on the memorial raised concerns about fire safety. Others say the decision to relocate the plaque was made to allow larger crowds to gather and pay their respects at the site every November 17. The plaque can be a little hard to find, as it’s so small. Your best bet is to head to the National Theatre, then backtrack up the street heading away from the river, and the plaque will appear on the right-hand side. Location: 1 Národní, Prague, 110 00 (Coordinates: 50.0816, 14.4134).

Special Thanks to Professor Josef Tomáš.

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Thank you in advance!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.