As you know, I love browsing through old books and magazines. Oftentimes I find a hidden treasure; a bit of information that time has filed away and which sits forgotten. I was looking through the September 9, 1969 issue of LOOK magazine and I came across this article written by the late Leonard Gross. It’s interesting how outsiders view things, and how they are presented to the rest of the world. This is his view of what had happened during the Czechoslovakian invasion 52 years ago today.

They slept that night in peace. The danger, they felt, had ended. Their democratic revolution would live. The Russians would not come in. As they slept, the chief of Czechoslovakia’s secret police, who was scheduled to lose his job within a few days, arrived at Prague’s new airport – to secure the field, he explained, for the arrival of an important Russian delegation. Within minutes, Czech and Soviet agents ringed the field, and airborne troops landed. At 1:00 a.m., the people of Prague awakened to the blaring of taxi horns and to news they could not at first believe.

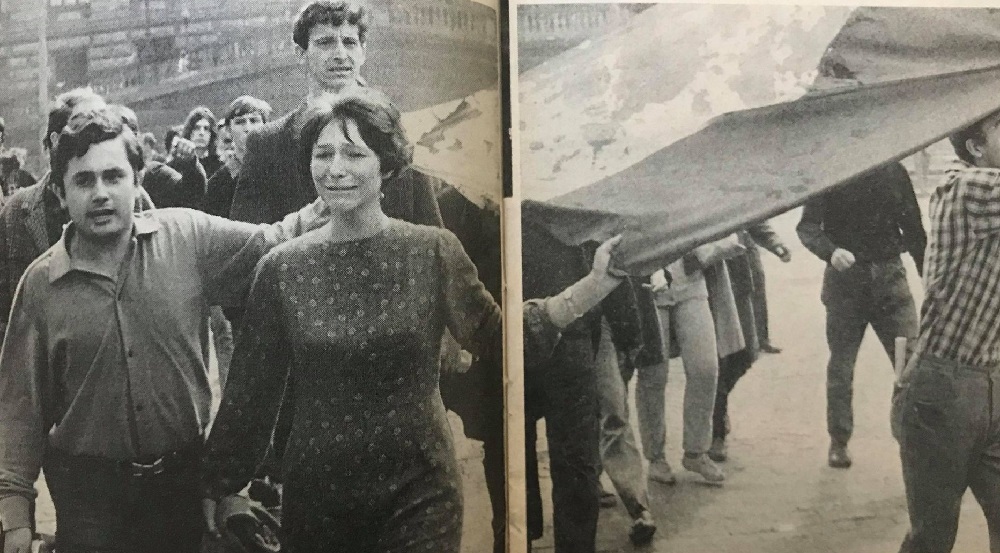

It was all a terrible mistake, they kept saying, and it would soon end, for we are the Russians’ friends. It was a mistake, but it did not stop. At 18 different points, Russian, Polish, East German, Hungarian, Bulgarian troops thundered across the borders of Czechoslovakia to suppress what they had been assured was a counterrevolution. They would be greeted, they were promised, by cheers. They were greeted instead by the sobs of the Czechoslovaks and the contempt of most of the world.

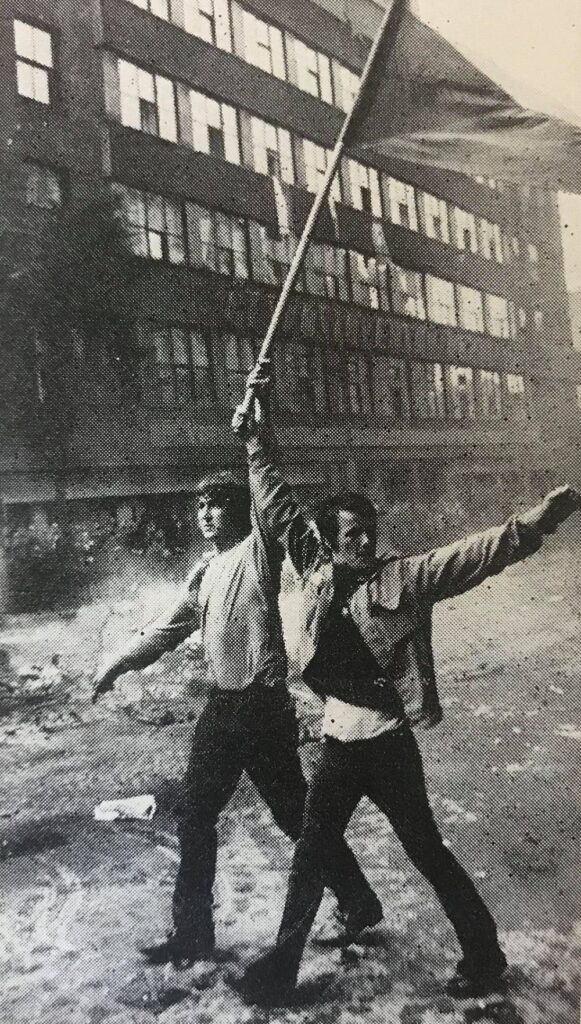

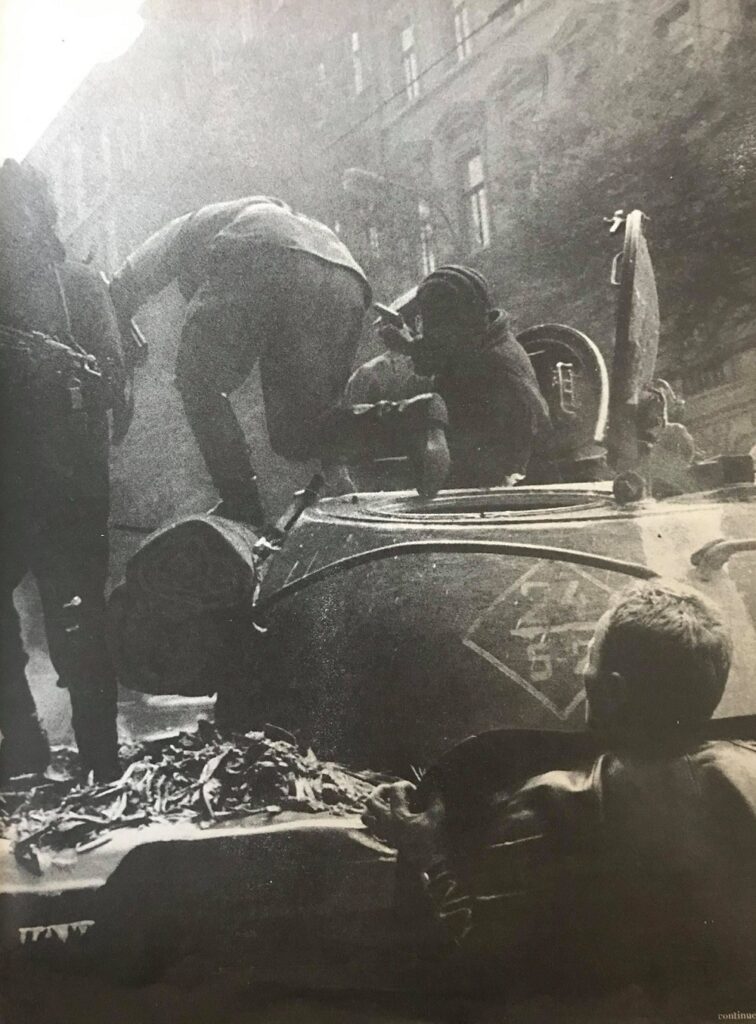

Students and workers raced to the Prague radio building. As long as the station could broadcast, the world would know what had happened. In May, 1945, Czech resistance fighters had seized the same building and come under heavy attack from the Germans. Now, 23 years later, Czechoslovaks built barricades against the Russian and other Warsaw Pact tanks, overturning buses, trucks and trolleys. When the tanks arrived, the Czechoslovaks pierced their reserve-fuel cylinders with pointed metal rods and set the fuel aflame.

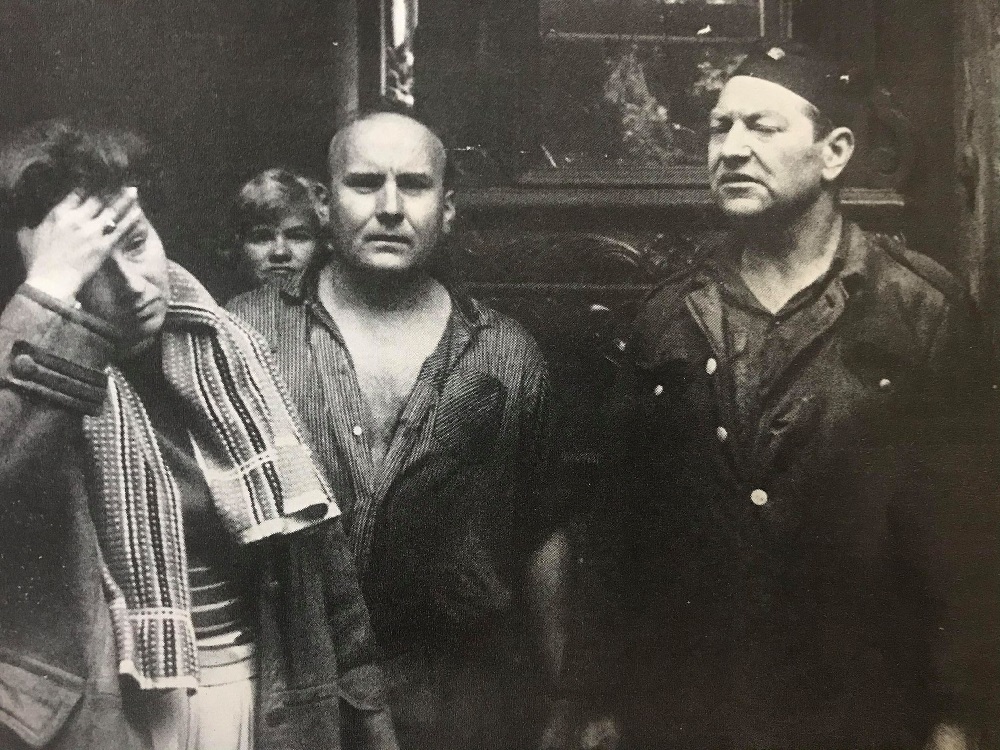

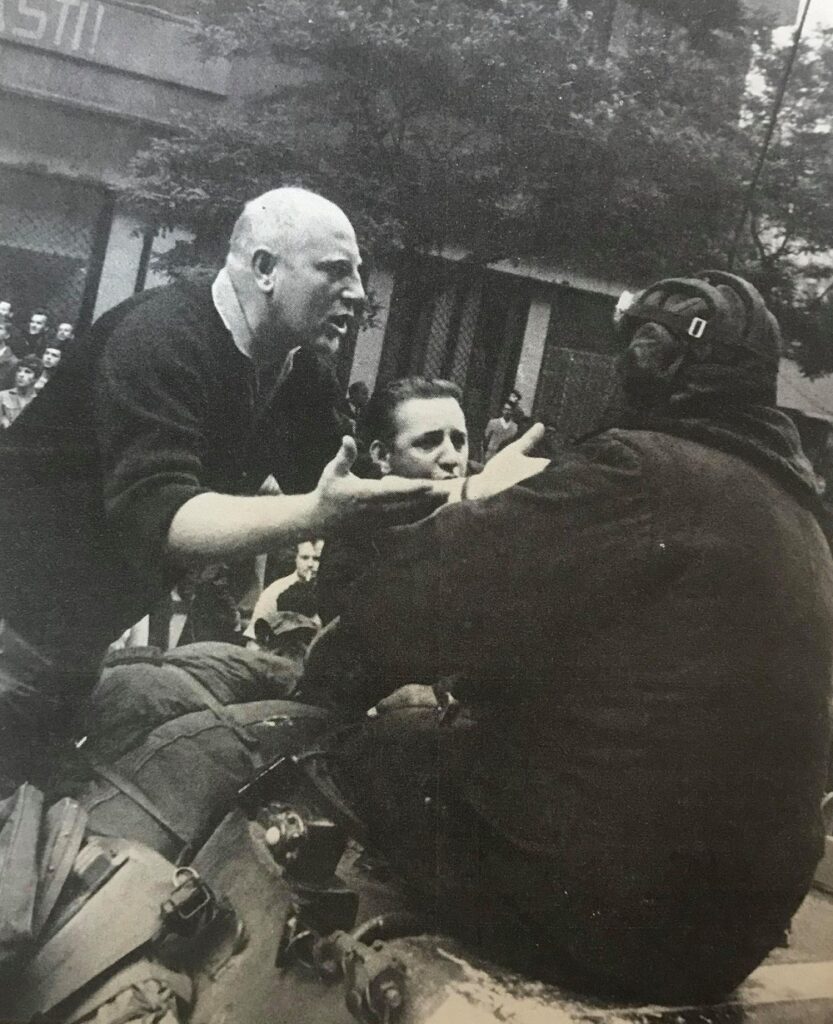

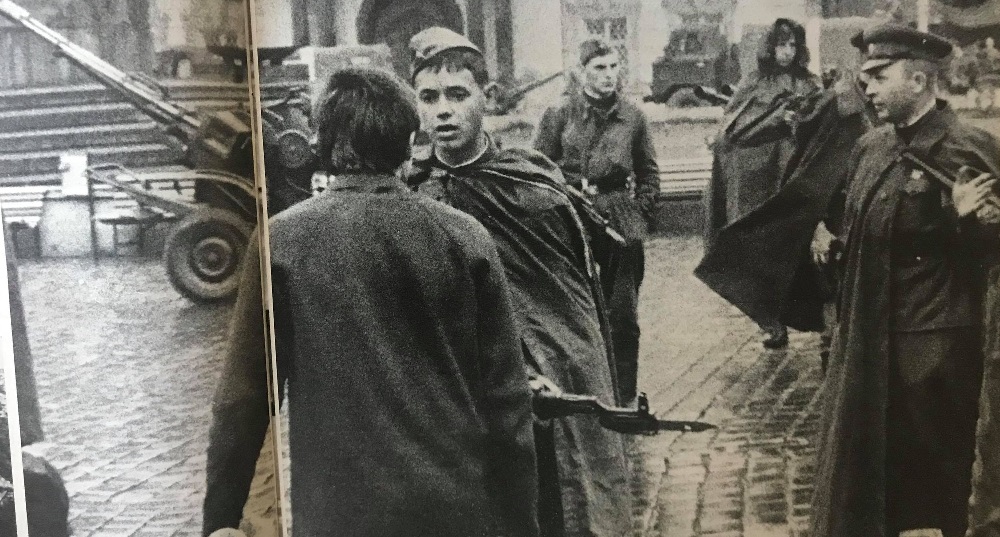

As the soldiers clambered out, the Czechoslovaks threw rocks and jibes. The invaders were ordered not to shoot. Through the night, most complied. But at 7:00 a.m., a rattled soldier fired – above, and then into the crowd.

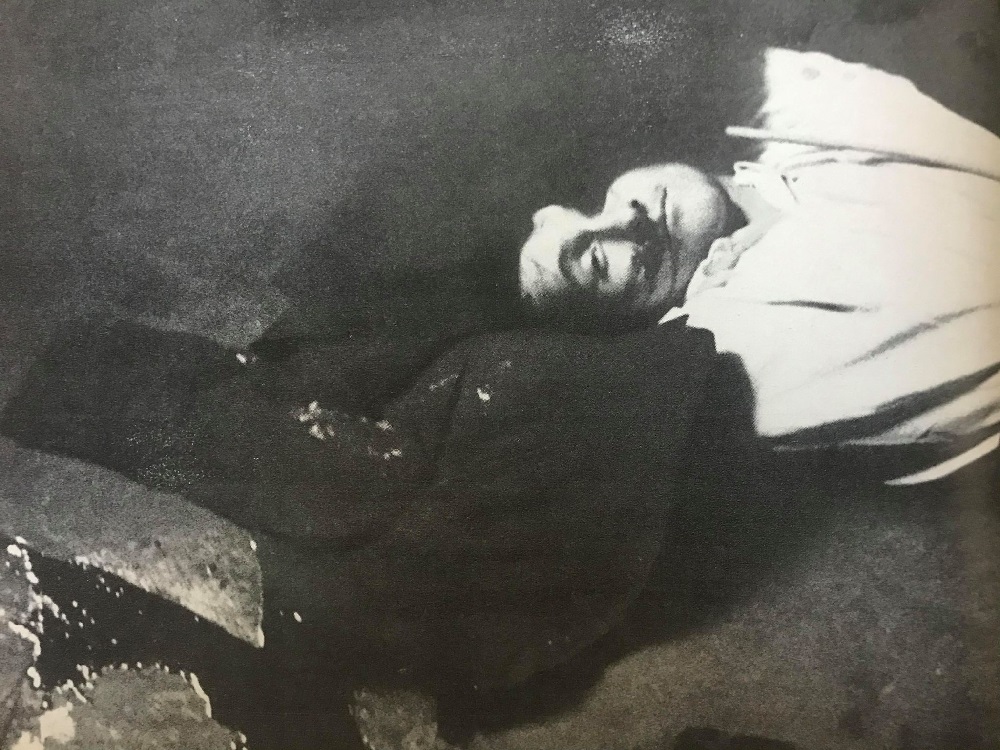

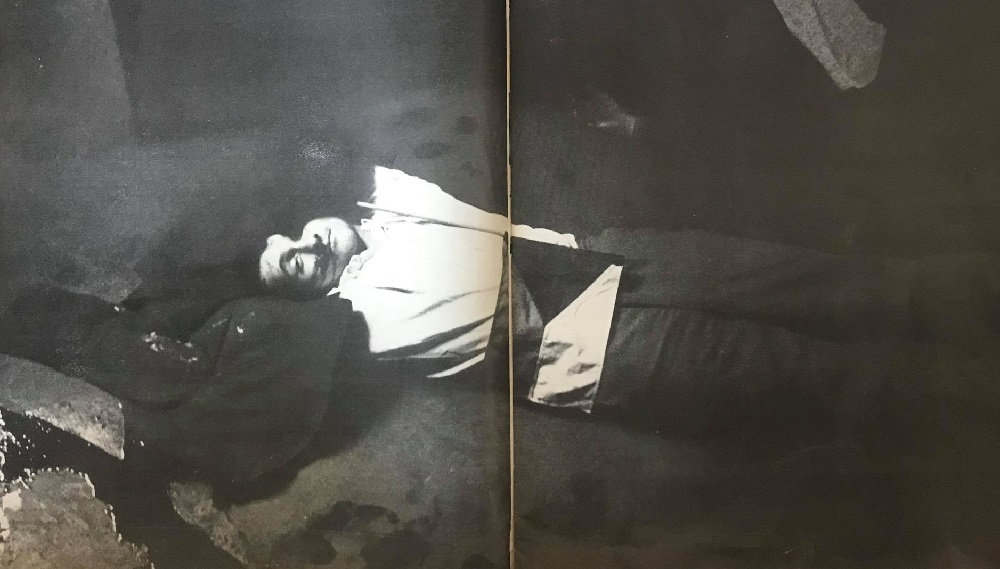

Three Czechoslovaks fell dead.

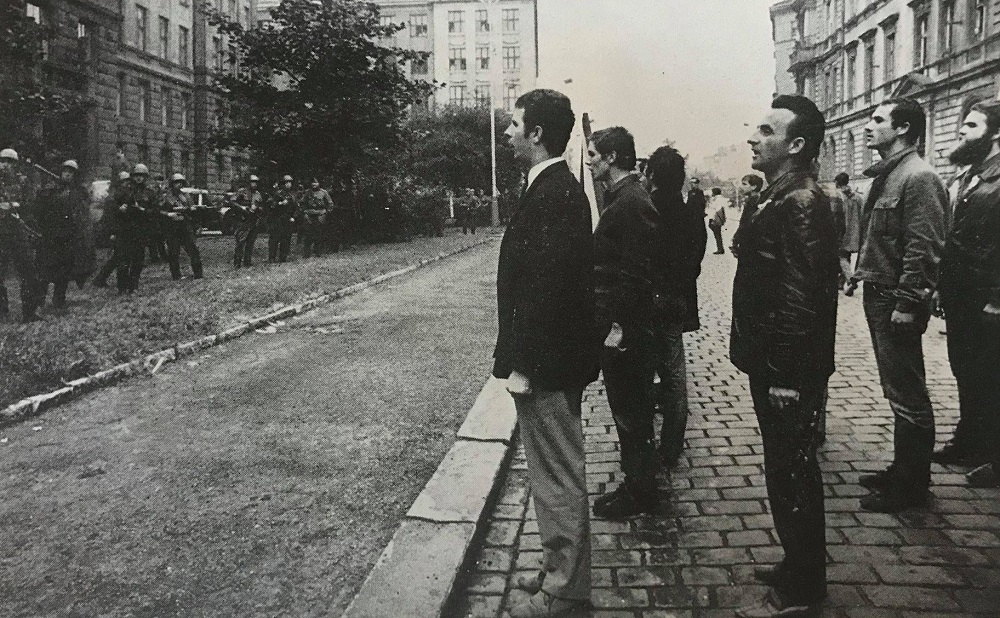

Violence was brief; armed resistance was impossible. Czech troops, their codes an open book since last summer’s Warsaw Pact maneuvers, were ordered not to fight. Few Czechs fought openly; only a few died – like these men of Prague below.

“They were disagreeable deaths,” one Czech said, “that will stink long and far.”

What the world would remember came next.

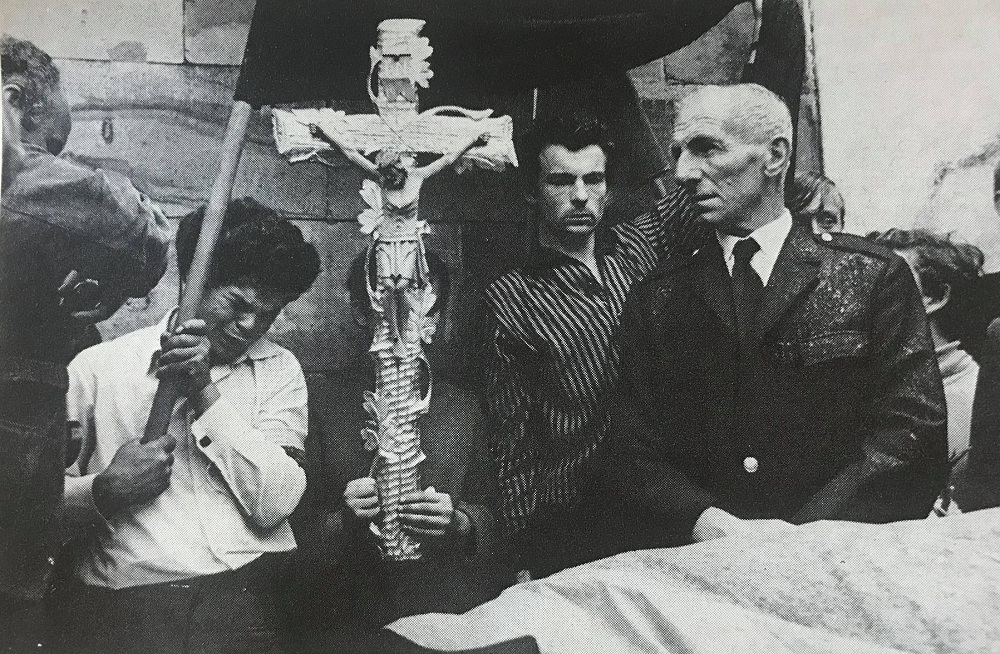

Out of sorrow welled ironic resistance.

The Czechoslovaks in effect turned Russian weapons against the invaders. The Russians captured the Prague radio building, but the Czechoslovaks held the airwaves. The Warsaw Pact defense system had honeycombed Czechoslovakia with radio stations to be operated in case of Western invasion. Now the stations went into operation against invasion from the East, to warn people, link cities, hold the country together.

Russian soldiers had been lectured that people shouting at them would be ‘anti-Socialists.” But the Czechoslovaks were shouting now in Russian (“Why have you come here?”) and reading them quotes in Russian, from Lenin – that no nation should dominate another.

The first wave of Russian soldiers was evacuated within 24 hours, the next, within three days. A woman overheard a kneeling Russian officer sobbing at the Russian World War II cemetery: “I am ashamed, I am ashamed.”

Until August, 1968, Czechoslovakia was the closest the Russians came to having a satellite friend. In 1948, 35 percent of Czechoslovaks were Communists; 75 percent, pro-Socialist.

Since then, they had watched with dismay as the most highly skilled country in Central Europe slid toward underdevelopment. The impetus of their quest for democratic Socialism was economic – they wished to infuse individual energy into an authoritarian system that had not worked for them.

This they knew: There was no future for them apart from Russia. They would always remain Socialists. But Russians are dogmatically paranoid. To any failure, they apply Stalin’s answer: “Conspiracy.” To them, that could mean anything: a flight from Socialism, a leap to the West. That was why they came.

Last August, Alexander Dubcek would have won an honest election. Today, the conservative Communist government is almost totally without support. “One thing it absolutely cannot do,” says a witness, “it cannot produce a nail.”

If one hope remains, it is that most of Czechoslovakia’s intellectuals are sticking. Says one, “We are much too involved in this country’s future, and we can’t just give it up.” But for Russia, the future is as irrevocable as death. It has managed to kill its friend.

History Lesson

The Warsaw Pact invasion of Czechoslovakia, officially known as Operation Danube, was a joint invasion of Czechoslovakia by five Warsaw Pact countries – the Soviet Union, Poland, Bulgaria, East Germany and Hungary – on the night of 20–21 August 1968.

Approximately 250,000 Warsaw Pact troops attacked Czechoslovakia that night, with Romania and Albania refusing to participate. East German forces, except for a small number of specialists, did not participate in the invasion because they were ordered from Moscow not to cross the Czechoslovak border just hours before the invasion.

137 Czechoslovakian civilians were killed and 500 seriously wounded during the occupation.

The invasion successfully stopped Alexander Dubček’s Prague Spring liberalisation reforms and strengthened the authority of the authoritarian wing within the Communist Party of Czechoslovakia (KSČ). The foreign policy of the Soviet Union during this era was known as the Brezhnev Doctrine.

Public reaction to the invasion was widespread and divided. Although the majority of the Warsaw Pact supported the invasion along with several other communist parties worldwide, Western nations, along with Albania, Romania, and particularly China condemned the attack, and many other communist parties either lost influence, denounced the USSR, or split up/dissolved due to conflicting opinions. The invasion started a series of events that would ultimately see Brezhnev establishing peace with U.S. President Richard Nixon in 1972 after the latter’s historic visit to China earlier that year.

The legacy of the invasion of Czechoslovakia remains widely talked about among historians, and has been seen as an important moment in the Cold War. Analysts believe that the invasion caused the worldwide communist movement to fracture, ultimately leading to the Revolutions of 1989, and the dissolution of the Soviet Union in 1991.

About the Author

Leonard Gross penned the above article about the Czechoslovakian invasion. Leonard Gross was the author, co-author or ghostwriter of 23 books, including several bestsellers and recently self-published The Memoirs of JFK, a novel based on interviews he conducted with 50 of Kennedy’s inner circle after the President’s death. Five other novels were dual main selections of the Literary Guild. Two days before he passed, Leonard’s nonfiction book The Last Jews in Berlin, hit #8 on the Amazon bestseller list and #5 on B&N when its new electronic publisher ran a promotional campaign.

In both his nonfiction and fiction work, Leonard’s themes echoed his strong convictions about the basic goodness of human beings, and our capacity and desire to solve problems. This concern for solutions extended to the personal realm. Over the years, he also co-authored or ghostwrote a series of books dedicated to self-improvement. You can read more about his life at his sons website.

About the Photographer

The article simply states: “Czechoslovakia – Exclusive photographs smuggled from Prague document the sorrows of a year ago, when a people struggling toward their dream of a democratic Socialism awoke to a nightmare of repression.”

To my eye, these images bear the signature of Josef Koudelka who turned full-time to photography in 1967. Koudelka was known for his photographs which documented the Soviet invasion of Prague and these have a similar look, though some I have never seen before. I’m feeling a bit frustrated that these images were uncredited by the publication, but perhaps at the time it was unknown.

We would love to hear what your thoughts are on this article in the comments section below. If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.