In the middle of a wide hilly region, with many forests and ponds, known as Bohemian-Moravian Highlands, lies an ancient town called Jihlava. When people think of the Czech Republic, most of them instantly have a visual image of Prague. But the lesser known city of Jihlava has a long and interesting history and is also worth a visit. Because I love old photographs so much, at the end of today’s post I am sharing a collection of black and white photographs from June of 1982.

Jihlava is the capital of the Vysočina Region, situated on the Jihlava river on the historical border between Moravia and Bohemia. Often historically referred to as Iglau, its German name, it exists as the oldest mining community in the Czech Republic. Legend says the silver was mined here in the year 799 which is approx. 50 years before much more famous Kutna Hora. King Ottokar I established a mint, and the city was granted extensive privileges during these early times.

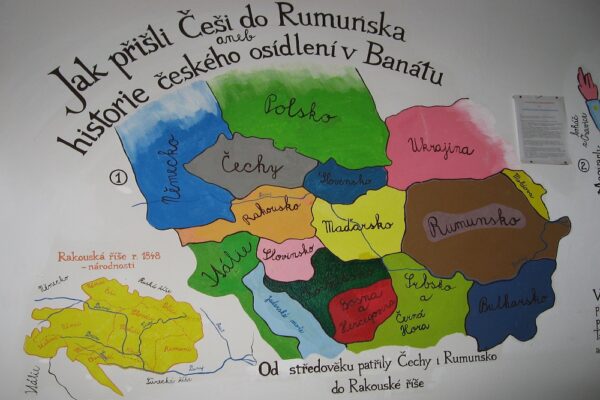

An old Slavic settlement upon a ford was moved to a nearby hill and almost 450 years later, the mining town was officially founded (ca. 1240) by King Wenceslaus I. In the Middle Ages the town was inhabited mostly by Germans (mostly from Northern Bavaria and Upper Saxony) hence the name Iglau. Medieval mines surrounded by mining settlements were localized outside the walls of the medieval town which at the time was named Staré Hory (Old Mountains).

In the era of the Hussite Wars, Jihlava remained a Catholic stronghold and managed to resist a number of sieges. Later at Jihlava, on July 5, 1436 to be exact, a treaty was made with the Hussites, whereby the emperor Sigismund was acknowledged King of Bohemia. A marble relief near the town marks the spot where Ferdinand I, in 1527, swore fidelity to the Bohemian estates.

During the Thirty Years’ War Jihlava was captured twice by the Swedes.

In 1742, it fell into the hands of the Prussians, and in December of 1805 it fell again to the Bavarians under Wrede were defeated near the town.

Glass with the sign of the cobblers’ guild of Iglau, 1722.

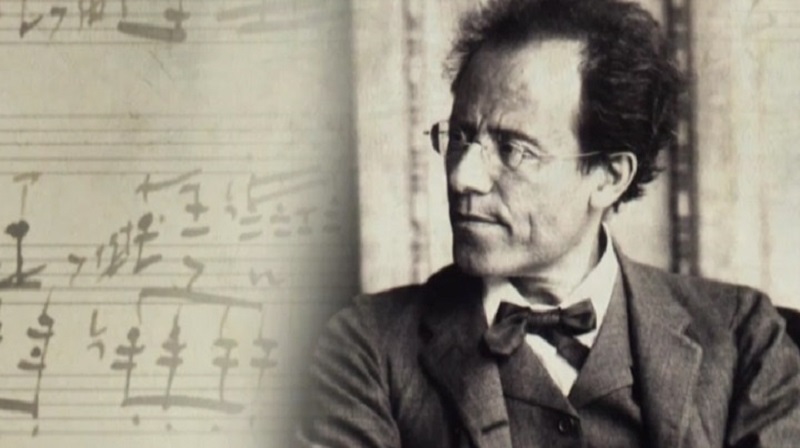

In 1860, it became the childhood home of Bohemian-Austrian composer Gustav Mahler, who retained his ties to the town until the death of both of his parents in 1889.

“Behind me the branches of a wasted and sterile existence are cracking.”

“I live like a Hottentot. I cannot exchange one sensible word with anyone.”

“It should be one’s sole endeavor to see everything afresh and create it anew.”

“I have become a different person. I don’t know whether this person is better, he certainly is not happier.”

“It’s not just a question of conquering a summit previously unknown, but of tracing, step by step, a new pathway to it.”

“It is strange how one feels drawn forward without knowing at first where one is going. If I weren’t the way I am, I shouldn’t write my symphonies.”

“When I have reached a summit, I leave it with great reluctance, unless it is to reach for another, higher one.”

“In its beginnings, music was merely chamber music, meant to be listened to in a small space by a small audience.”

“The call of love sounds very hollow among these immobile rocks.”

“Don’t bother looking at the view – I have already composed it.”

Until World War I the town was an important Austro-Hungarian Army military center. In 1914, the First, Second and Third Battalions of the Moravian Infantry Regiment No. 81 (Bataillon des Mährischen Infanterie-Regiments Nummer. 81) and the Second Battalion of the Landwehr infantry regiment number 14 (II. Bataillon des Landwehr-Infanterie-Regiments Nr. 14) were the garrison troops.

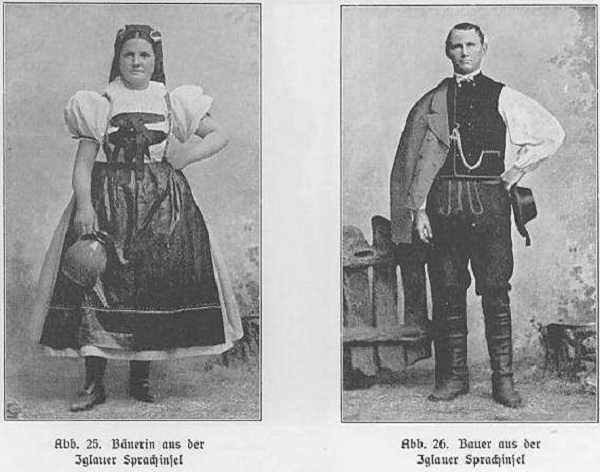

After World War I the town constituted a German language island (Sprachinsel) within Slavic-speaking Moravia. This affected local politics, as it remained the center of the second-largest German-speaking enclave in the republic of Czechoslovakia (after Schönhengstgau/Hřebečsko).

After the Czechoslovak Republic was proclaimed on October 28, 1918, the indigenous Germans of Bohemia and Moravia, claiming the right to self-determination according to the 10th of President Woodrow Wilson’s Fourteen Points, demanded that their homeland areas remain with the new Austrian State. The Volksdeutsche of Iglau relied on peaceful opposition to the Czech military occupation of their region, a process that started on October 31, 1918 and was completed on January 28, 1919. Unsuccessful in getting their right to self-determination recognized and incorporated into the new Czechoslovakian state, many of the indigenous Germans instead took to more nationalistic politics. Thereafter extremist political figures like Hans Krebs, editor of the Iglauer Volkswehr newspaper, became prominent with the rise of Nazism and the Nazi occupation (1939–1945).

Krebs was apparently in communication with Adolf Hitler, and was also a member of the Czech Parliament several times. In 1933 he was stripped of his parliamentary immunity and imprisoned. Krebs then fled to Nazi Germany, where he became a member of the Schutzstaffel (SS). He was soon promoted to the rank of SS-Brigadeführer. In the mid-1930s he wrote two books arguing the Sudeten German case: Kampf in Böhmen (Berlin, 1936); Wir Sudetendeutsche (Berlin, 1937). Having become a nationalist early, he along with Rudolf Jung and Hans Knirsch, was one of the few original Moravian National Socialists to remain in the party after 1933. During the Sudeten Crisis, Heinrich Himmler and the SS favored Krebs over Konrad Henlein, and tried to play them off against one another to some degree. Krebs returned to Moravia in 1939 and participated in persecuting political opponents of the Nazi regime. He was appointed Oberregierungsrat im Reichsinnenministerium (Chief executive officer in the Reich Ministry of the Interior) and apparently had this job during World War II. After the war Krebs was convicted of high treason, and executed by the Czechoslovak government in Prague in 1947.

Until the end of World War II, Jihlava was the center of a distinctive regional folk culture reflecting hundreds of years of local customs. The local dialect of German was a unique branch of Mitteldeutsch. Musicians often used homemade instruments and original groups of four fiddles (Vierergruppen Fiedeln) and Ploschperment.

four-string clarified, a three-string coarse and a bass violin, which is called “Ploschperment”.

Typical folk dances were the Hatschou, Tuschen and Radln. Peasant women wore old “pairische” Scharkaröckchen costumes with shiny dark skirts and big red cloths.

In the following video, you can see the traditional instruments played as well as several of the Czech-German folk dances in the regional folk kroje.

Jews played an important role in developing Jihlava’s textile industry. In 1709, Jewish merchants were permitted to trade in the town upon payment of a special tax, but they were required to leave by nightfall. A few Jews were granted special permission to reside in Jihlava at the end of the eighteenth century; by 1837, a total of 17 Jews lived there legally. Jews began arriving in larger numbers following the Revolution of 1848, and the population grew rapidly after residential restrictions were lifted in 1860. There were 99 Jews in 1848; 221 in 1857; 1,090 in 1869; 1,415 in 1880; and 1,450 in 1900.

Jihlava’s first house of prayer was established in 1856; a religious congregation was officially recognized in 1862; a Moorish-style synagogue was dedicated in 1863; a cemetery was consecrated in 1869; and a burial society was established in 1870. From 1890 onward, Jihlava’s religious congregation encompassed 31 towns and villages in the surrounding region. Jihlava was a German-speaking enclave; its Jews tended to identify with German language and culture until the rise of Nazism. Most of Jihlava’s Jewish population was deported and killed due to the Holocaust in Bohemia and Moravia. You can learn more about the Jewish population of the area by visiting Jewish Families of Jihlava (Iglau) and reading this page.

After the end of World War II, and following the Beneš decrees, the German speakers were completely evicted and it is estimated that hundreds died on the arduous trek to Austria. The town was then repopulated with Czech and Moravian settlers favored by the new Communist regime.

After 1951, the town was the site of several Communist show trials, which were directed against the influence of the Roman Catholic Church on the rural population. In the processes, eleven death sentences were passed and 111 years of prison sentences were imposed. All the convicted persons were rehabilitated after the Velvet Revolution.

In protest against the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia in 1969 Evžen Plocek set himself on fire in the town marketplace in emulation of others in Prague. Today there is a memorial plaque to him.

Since the collapse of Communism in the 1990s the share of employment in agriculture has steadily declined. The industrial sector of the town now employs 65 percent of all workers. In 2004, the Jihlava Polytechnic was set up and now has about 2,600 students.

A place to visit while there is certainly the Gustav Mahler House.

And now a tiny little peek to a trip back in time to the summer of 1982 in Jihlava…

If you enjoyed the above 3 photographs, you will certainly enjoy the entire album we have posted at Time Travel to Jihlava in 1982.

Additionally, you may also like When Prague was 50 Shades of Grey.

Thank you in advance for your support…

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks, and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

We appreciate you more than you know!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.