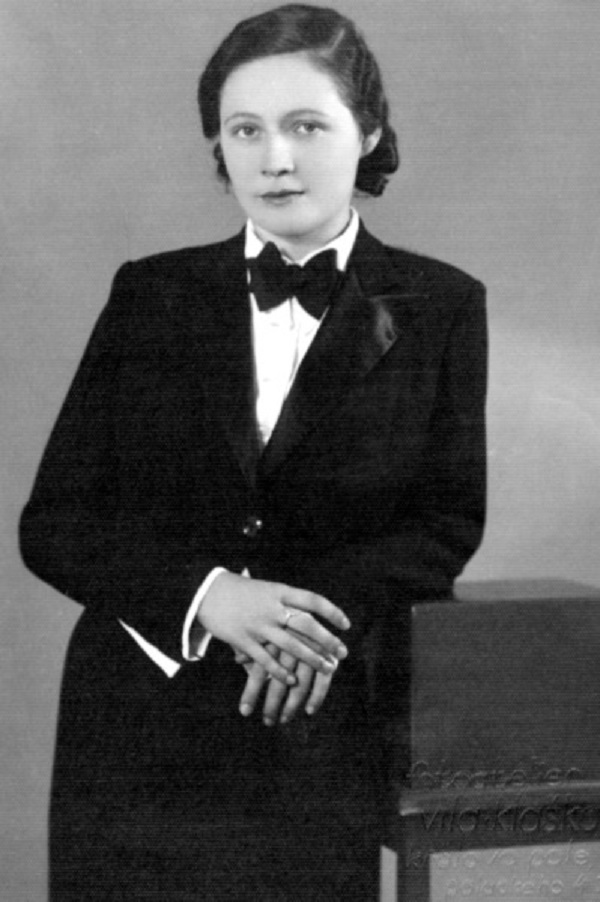

Despite her tragically brief life, Vítězslava Kaprálová, who died at the age of twenty-five, is now considered the most important female Czech woman composer of the 20th century. Her prolific output, abundant with fresh and bold ideas, passion, tenderness and youthful energy are once again coming to light.

Muse (and mistress) of Bohuslav Martinů and wife of Jiří Mucha (son of the great Art Nouveau painter, Alphonse Mucha), she composed no fewer than fifty works in her very short life.

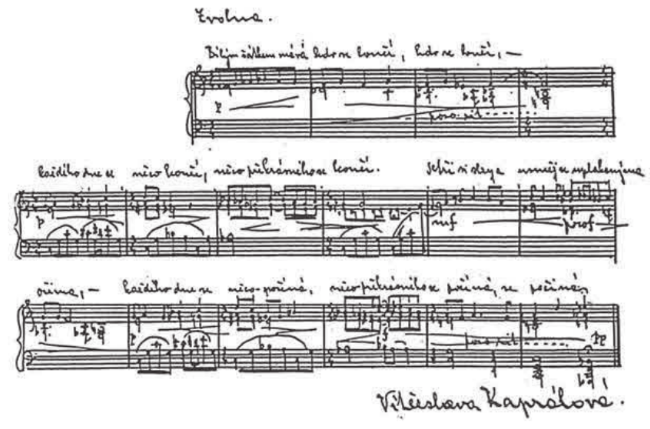

Kaprálová is remembered for her innovative approach to melody; counter-intuitive but not dissonant, upbeat but never silly, it represents a point of connection between the romantic and modernist traditions. It is hard not to suspect that, had she lived to old age and continued to explore the contradictions at which her music hints, she might well be remembered today as the single most influential composer of the 20th century.

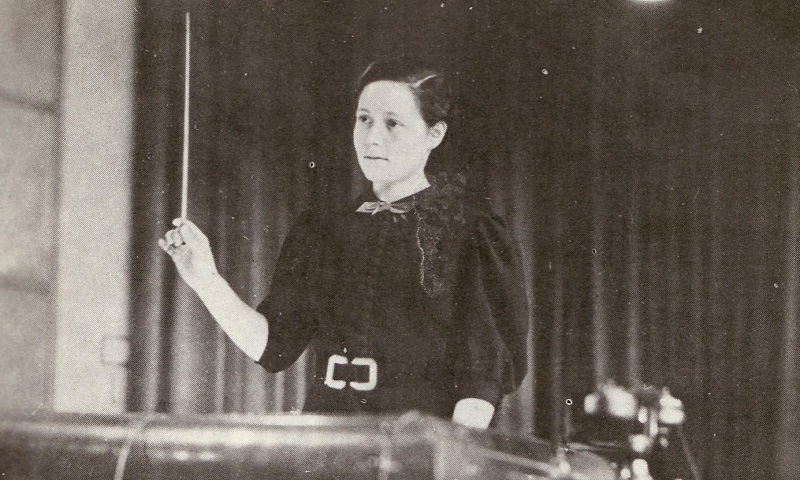

When she died in exile in France at the age of twenty–five, Vítĕzslava Kaprálová was on the threshold of a successful international career as a composer and conductor.

During her short life, she composed no fewer than fifty works (many of which were published), conducted orchestras in Prague, London, and Paris, was praised by music critics across Europe, and was awarded the Smetana Award by the Bendřich Smetana Foundation – all within a very short time span.

Vítězslava Kaprálová is considered an important representative of twentieth-century Czech music and the most important Czech woman composer. She was a daughter of composer Vaclav Kapral and voice teacher Vitezslava Uhlirova. She was born in January 24, 1915 in Brno – then still in the Austro-Hungarian Empire but later part of Czechoslovakia.

A child prodigy, she started composing at nine, and at fifteen she entered the Brno Conservatory where she studied composition with Vilem Petrzelka and conducting with Zdenek Chalabala and Vilem Steinman (1930-1935).

She continued her studies with Vitezslav Novak and Vaclav Talich at the Master School of the Prague Conservatory (1935-1937). In 1937, Kapralova conducted the Czech Philharmonic and a year later the BBC Orchestra in her Military Sinfonietta, to much critical acclaim.

She further advanced her musical education at the Ecole normale de musique in Paris with Charles Munch (1937-1938) and, according to some unverified accounts, with Nadia Boulanger (1940), while also studying composition privately with Bohuslav Martinu (1938-1939).

In 1937, Bohuslav Martinů visited the city of Prague to prepare for the premiere of his opera Julietta. During that visit, he met Czech woman composer Vítĕzslava Kaprálová. Beautiful and talented, she was twenty-five years younger than Martinů, and had long admired the older composer. It might well have been love at first sight for both, and so it was quickly decided that she should continue her studies with him in Paris.

Kaprálová managed to secure a scholarship and by October 1938 was studying conducting with Charles Munch and composition with Martinů in Paris. She became his student and his lover, and they began composing wind trios to rival each other.

They even composed respective “Love Carols” for each other. Martinů was hopelessly in love with Vítĕzslava, and vice versa. The trouble was that Martinů was still a married man!

She lodged in a hotel overlooking the Luxembourg Gardens, and Martinů showed her the city. He called her Vítĕzslava Pisnicke (Little Song), and she mysteriously nicknamed him Špalíček (little chunk of wood), but his wife, the seamstress Charlotte Quennehen soon received anonymous letters telling her of the clandestine affair. Charlotte did not want to believe the content of the letters and simply threw them away. By late summer of 1938, Vítĕzslava’s scholarship had expired and she was forced to return to her native Czechoslovakia.

Between September 11 and December 31, 1938, Martinů wrote her thirty-seven letters and a picture postcard. “I am so longing to see you,” he wrote, “and I know that you belong to me and only me and then I can’t believe that you could only be mine. You are my only sunshine, my only warming ray that gives me courage and I just can’t see how I could stand it if you don’t come and if you were not with me all the time. Can’t you understand how I feel when I cannot exist without you and when I see you going further and further away?”

Martinů loved her to the end of his life, and in 1947 wrote in his memoirs:

Everywhere she went she brought Spring. She was patient, kind, friendly, energetic, and instinctive. I seldom had the chance to meet anyone so gifted, so conscious of the task she had and wanted to fulfill. And this is one of the things I cannot explain, why fate took her, why fate gave her such gifts, so precious and unique, only to take them away.

Martinů’s and Kaprálová’s relationship is artistically encoded in a number of compositions that originated during their affair. Her Partita is a close imitation of his compositional style, and his String Quartet No. 5 is one of his most confessional and intimate musical expressions.

Shortly before the Nazi occupation of France, Kaprálová became (terminally) ill. As World War II spread across the European continent at the end of 1939, the political unrest grew in Paris and across France.

Martinů and his de facto wife, Charlotte, started to make plans to leave France, and Martinů and Kaprálová began to spend less time together. Finding herself more and more alone in Paris, Kaprálová began to realize that a future with Martinů was not in her best interest. Although she stayed on friendly terms with Martinů and even had a couple of composition lessons, her attention had shifted to the Czech writer. She told a friend that Martinů was simply too old for her, and that he was incapable of leaving his wife.

The young Czech she met was named Jiří Mucha, the son of the great Art Nouveau painter, Alphonse Mucha. They grew very close. Being of similar age and with similar interest in the events happening in their common homeland, the two began to spend more time together while in Paris.

On April 23, 1940, Kaprálová and Mucha were married in Paris. Although Mucha had enlisted in the French army, the two continued their relationship. Just a week later, the first signs of the illness that would take Kaprálová’s life were documented.

Although she managed to maintain her musical activities in Paris, continuing to compose, publishing articles, and directing the newly formed Czech women’s choir in Paris, the illness rapidly took its toll.

She was in and out of the hospital for several weeks and on May 20th was evacuated by Mucha from the increasingly stressful conditions in Paris to a hospital in Montpellier.

The day before her evacuation, Kaprálová saw her mentor and teacher, Martinů, for the last time. He wrote to her after that:

You don’t write so I assume that you must have had your surgery and that I have to be patient and believe that everything will now turn to the better. Well, perhaps not everything but at least all that concerns you, and so as soon as it is possible, write me a letter or send me good news, will you? This is such a surreal world in which we all live, and I in particular, because for me something has ended so abruptly, something that was filling my life or at least a big part of it, and now it is over so suddenly, so quickly that I haven’t been able to fully process it because those other events cover and deafen it, and the same may have been happening to you, and then in a flash of a moment I catch a glimpse of something resembling a memory, a glitter of light, a distant little image as if one looks through the wrong end of binoculars, a kind of a miniature landscape, so minuscule and yet with everything in place, but in a rather unusual way.

On June 14, the German’s occupied Paris.

Tragically, two days later on June 16, 1940, with her husband Mucha by her side, Czech woman composer Vítĕzslava Kaprálová died in Montpellier, France.

While the stated cause of death was miliary tuberculosis, few contemporary scholars accept that diagnosis; surviving documents suggest that her symptoms were more consistent with those of peritonitis.

Despite her untimely death in 1940, from what was misdiagnosed as miliary tuberculosis, Kapralova left behind an impressive body of work. Her music was much admired by Rafael Kubelik who premiered her orchestral song Waving Farewell and performed several other works; so did Rudolf Firkusny, for whom Kapralova composed April Preludes and Two Dances for Piano.

In 1946, in appreciation of her distinctive contribution, the foremost academic institution in the country – the Czech Academy of Sciences and the Arts – awarded Kapralova membership in memoriam. By 1948 this honor was bestowed on only 10 women, out of 648 members of the Academy. Only one of the ten women was a musician – Kapralova.

Kapralova’s creative output includes her highly regarded art songs and music for keyboard, music for cello and piano, violin and piano, a reed trio, a string quartet, two piano concertos, a concertino for clarinet, violin and orchestra, two orchestral suites, a sinfonietta, two choruses, and a cantata.

Some of Kapralova’s music was published during her life (Pazdirek, HMUB, Melantrich, and La Sirene éditions musicales), and continued to be published following the composer’s death (some works in multiple editions) by various publishing houses at home and abroad (Svoboda, Editio Supraphon, Editio Praga, Amos Editio, Egge Verlag, Certosa Verlag, and Czech Radio).

Kapralova’s music has been released on record by Supraphon, on compact disc by Naxos, Delos, Koch Records, Supraphon, Gramola, ARS Production, Northeastern Records, Albany Records, Centaur Records, Czech Radio (Radioservis), Studio Matous, Arco Diva, Stylton Records, and others, and as digital audio by Supraphon, Radioservis, and Wave Theory Records.

Starting in the last two decades of the twentieth century, interest in Kaprálová began to re–emerge. In 1988, Jiří Mucha published a memoir of his life with Kaprálová entitled, Podivné lásky (Strange Loves). The following decade saw the publication of a fictional account of Kaprálová’s relationship with Martinů.

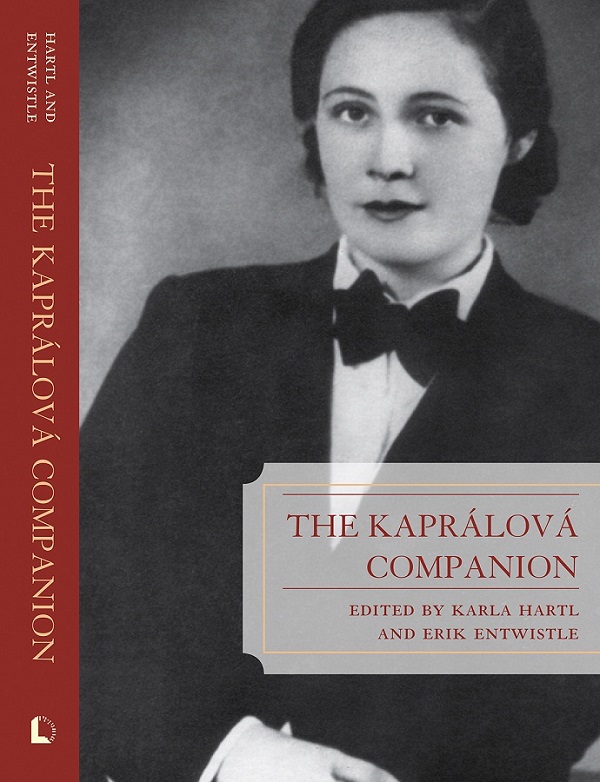

Scholarly interest in Kaprálová and her music received a healthy boost from the work of Karla Hartl and the Kaprálová Society in their book The Kaprálová Companion. Several of Kaprálová‘s works were also performed and recorded by musicians around the world. Perhaps Kaprálová, a promising composer and musician and young victim of World War II, is now once again on her way to becoming an important part of the early Czechoslovak modernist movement.

Kapralova’s life has inspired two Czech language monographs, two novels, and other books. In 2011, a long-overdue English language book on Kapralova was published by Lexington Books (Rowman & Littlefield) in the United States; a French language monograph on the composer followed in 2015 and a German language publication in 2017.

Furthermore, since 2015, The Kapralova Society has been publishing an important anthology of Kapralova’s correspondence. On the occasion of the composer’s centenary in 2015, BBC Radio 3 featured Kapralova as their Composer of the Week, dedicating five hours of programming to her music.

Another wonderful write up can be found at the following: Jakub Hrůša’s reflections #9, “She and Martinů”. Wonderful reading!

The Kapralova Society is a Canadian non-profit music society, founded in 1998 in Toronto. An affiliate member of the International Alliance for Women in Music, the Society’s mission is to promote interest in Kapralova and other women in music through research, education, and special projects, often in partnership with schools of music, public broadcasters, publishers and other organizations.

In popular culture, you may be aware of her work from the television series, Mozart in the Jungle because Vítězslava Kaprálová’s work and life were featured in episodes 6 and 9, season 3.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, 8, 9, 10.

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Beautiful music and a great talent.

A woman ahead of her time.