Today we have a wonderful history of the Czech flag to share with you. This special guest post was a paper originally published by NAVA (North American Vexillological Association) in the Proceedings of the 24th International Congress of Vexillology (2011). It was written by Aleš Brožek and is reproduced here with permission.

The outbreak of the First World War in 1914 gave the Czech people the opportunity to be free. While most lived in Central Europe under the Austro-Hungarian monarchy, an estimated 650,000 Czechs made their homes in America at that time. Adding American Slovaks, the population from these two Slavic nations in America could reach 1 million. They started to immigrate to America in the second half of the 17th century. The mass immigration, however, began after 1848 and the largest number of immigrants settled in industrial centres in the northeast U.S.A.

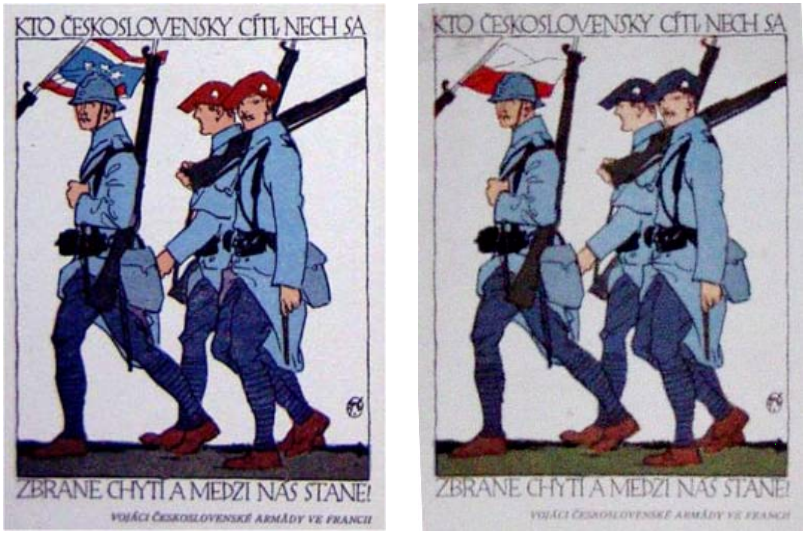

After the declaration of war, protest rallies of Czech and Slovak countrymen were organized in main centres of the United States under American flags (Fig. 1). A demonstration of Czech, Slovak, and Serbian countrymen took place in the Pilsen pavilion in Chicago on 28 July 1914. The symbols of Austria-Hungary that were placed in the room were whipped off in the beginning of this demonstration. (1)

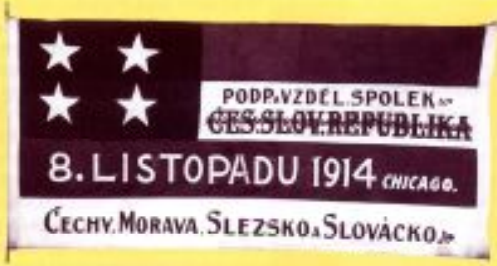

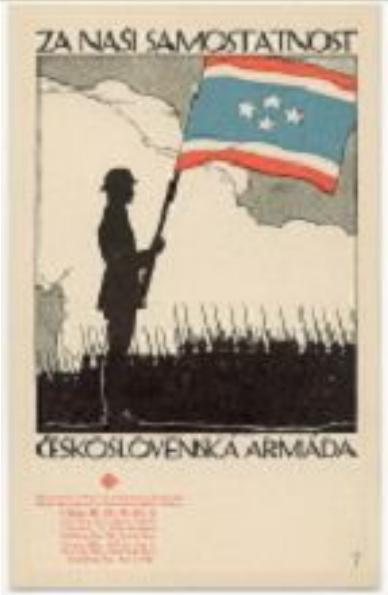

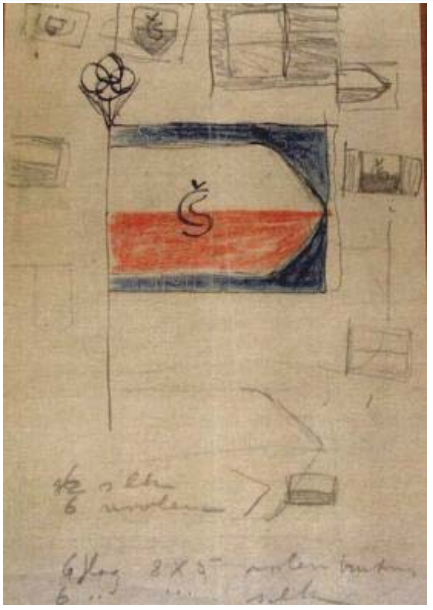

A revolutionary club called “Československá republika” (Czechoslovak Republic) was established in Chicago on 8 November 1914. It is said that its bookkeeper Josef Křivanec presented a design for a flag of the future state, created by the club’s chairman, Bohuslav Duffek. It was designed during a meeting of a preparatory committee on 12 September 1914 when it gained more votes than a traditional design of a white over red flag with the Bohemian heraldic lion. The winning design had four horizontal stripes, red over white over red over white, and a blue canton with four white stars standing for Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, and Slovakia. (2) A public notice showing this flag, which bears the name of the club and the date of the club’s founding (Fig. 2), is held in the Army Museum in Prague. (3) However, the club was not very influential and therefore its flag design did not become popular. Even the idea of a republic was premature at that time.

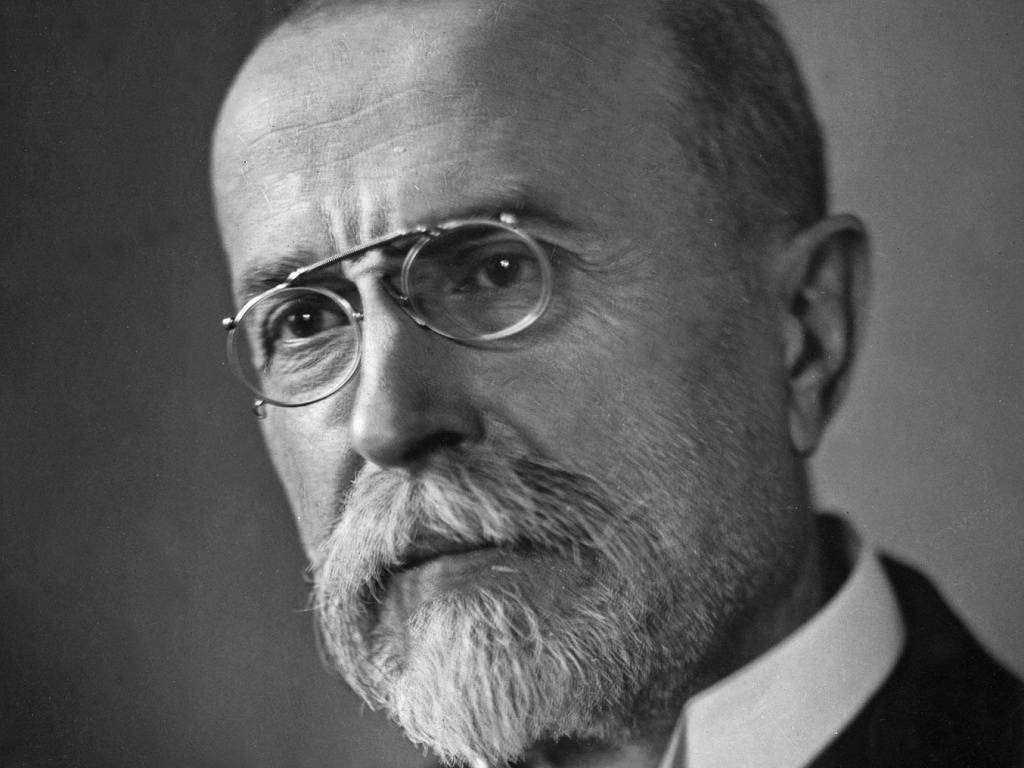

The effort to coordinate collective action in America reached a peak in the establishment of the Bohemian (Czech) National Alliance in September 1914. Together with the Slovak League they supported the major representative of the resistance movement—the Czechoslovak National Council in Paris (recognized as a provisional government in 1918). Its leader, Tomáš Garigue Masaryk, a Czech and the first president of Czechoslovakia, concluded that the best course was to seek an independent country for Czechs and Slovaks, and that this could only be done from outside Austria-Hungary. The formation of an autonomous army became a vital task for him. Therefore Milan Rastislav Štefánik, a Slovak and the vice-president of the Council, began recruiting Czechoslovak troops in France, Italy, and Russia.

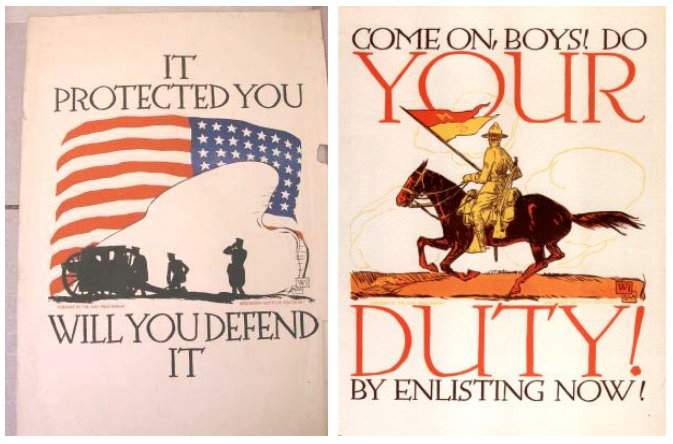

In June 1917 Štefánik came to the U.S.A. to support the campaign to recruit volunteers into the American and Canadian armies. He met Czech artist Vojtěch Preissig and admired his patriotic enthusiasm and artistic skill. Vojtěch Preissig had worked on propaganda posters since December 1916 and together with his student and friend Frederick Trench Chapman made two flag posters showing American flags in the spring of 1917. One poster depicted the American national flag, the other an American army guidon (Fig. 3).

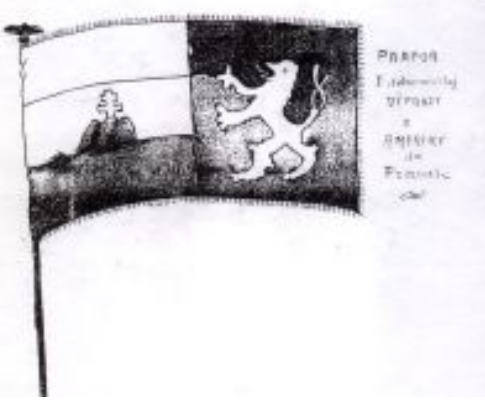

Preissig was asked to design army flags in September 1917 because the first groups of Czech and Slovak volunteers were being shipped from America to France. The lack of Preissig’s time and ideas meant that the first detachment left America on the liner Madona with a flag created in haste. It consisted of the Slovak tricolour (white over light blue over red) with the white so called Patriarchal Cross (the double cross) atop a dark blue threepeak hill in the central stripe in the hoist part of the flag. The white double-tailed Bohemian lion without his golden crown was on a red fly edge (Fig. 4). The designer of this flag is unknown. (4)

An article from The Boston Traveller of 12 November 1917 supports the fact that Vojtěch Preissig did work on an army flag for Czech soldiers at that time. A journalist named Esther Harney, reporting on a meeting of the Bohemian Club in Boston, mentioned Preissig as a flag designer and wrote that “a new flag of the Czechoslovak army was proposed yesterday. If it is adopted, Bohemian women in America, directed by Mrs. Preissig, will embroider the flag which their countrymen are to carry on the fields of battle as allies of France, and Mrs. Preissig will then become the Betsy Ross of her country”.

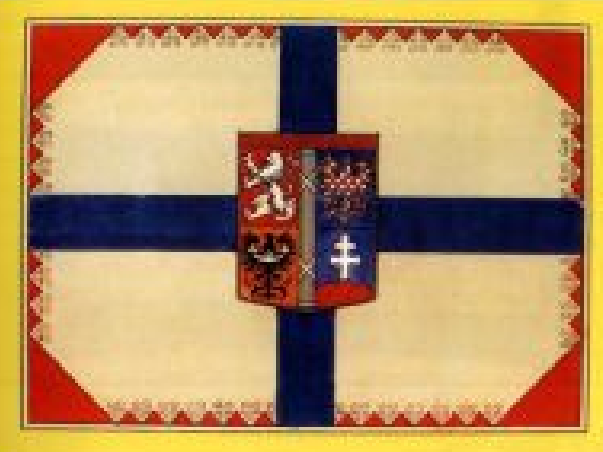

We are not quite sure of the design of this flag. It may have been be similar to another one which is deposited in the Army Museum in Prague and which is characteristic with a blue cross and the arms (Fig. 5) that were used by the Czechoslovak National Council and designed by a Czech graphic artist Rudolph Růžička from New York.

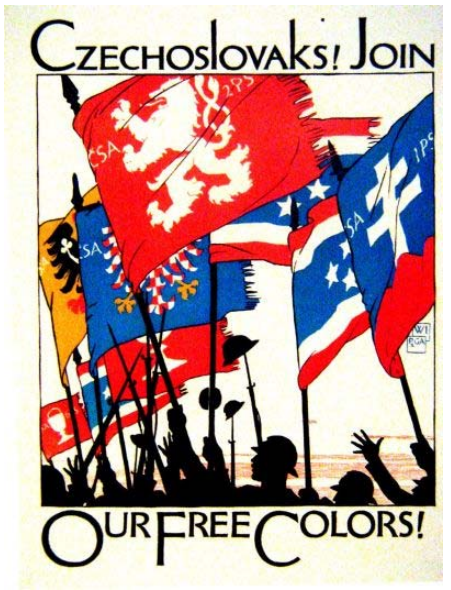

From the end of November 1917 Preissig devoted his ideas and skills to designing recruiting posters which brought him great success not only in America but also abroad. The famous poster with the motto “Join Our Free Colors!” (Fig. 6) appeared among the first ones. (5)

Nine army flags were flying over the soldier’s heads. Most of them are heraldic flags. The foremost one is derived from Bohemian arms (a red field with the white Bohemian lion); the flag on the right side was erroneously derived from Slovak arms (its field should be red and hills blue). Behind these two flags there are flags derived from Moravian arms (a blue flag with the Moravian eagle) and from Silesian arms (a yellow flag with the Silesian eagle). Two red flags with a white chalice recall the Hussite Wars (named for Jan Hus, a Czech priest and reformer), which broke out in Bohemia in the early 15th century. A special flag contains five horizontal stripes, red, white, blue, white, and red. In the middle of the broad blue stripe there are four white five-pointed stars. This new flag became very popular because it was easy to make. It contained not only Bohemian colours (white and red) but also Slovak colours (white, blue and red) and stars standing for Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, and Slovakia. Unfortunately, Preissig never explained if it was his own idea or if another person influenced him. An article explaining the symbolism of this flag published in a journal “V boj” on 10 August 1918 wrote “a flag designed by artist Preissig”. However, in 1990 a Slovak historian Vladimír Zuberec published a photo of a cloth flag in the Historical Museum in Bratislava in Slovakia (Fig. 7) with a subtitle “A design of Milan Rastislav Štefánik and artist V. Preissig”. (6) This flag differs only little (the stars are turned a little in a clockwise direction) from the one on posters. Although Preissig met Štefánik in July 1917 and wrote him several letters, influence by Štefánik on the design seems rather unlikely.

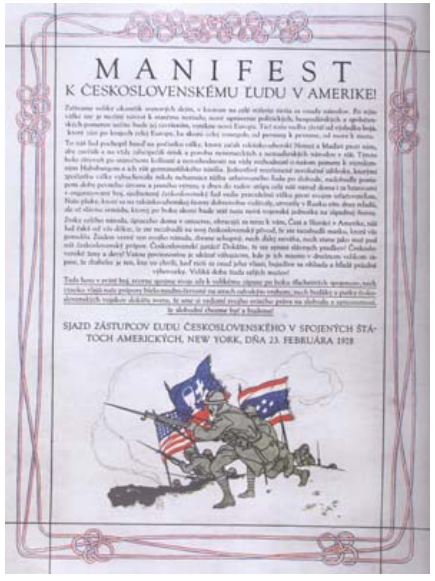

In February 1918 the Bureau of Military Affairs of the Czechoslovak National Council branch in America asked Preissig to print two posters. He placed this four-star flag accompanied by an American flag and a flag containing a chalice and a cross on the first poster below the text of a manifesto to the Czechoslovak people in America (Fig. 8).

The other poster (Fig. 9) was to recruit Slovak people and the four-star flag has a different position of stars, all are in one row.

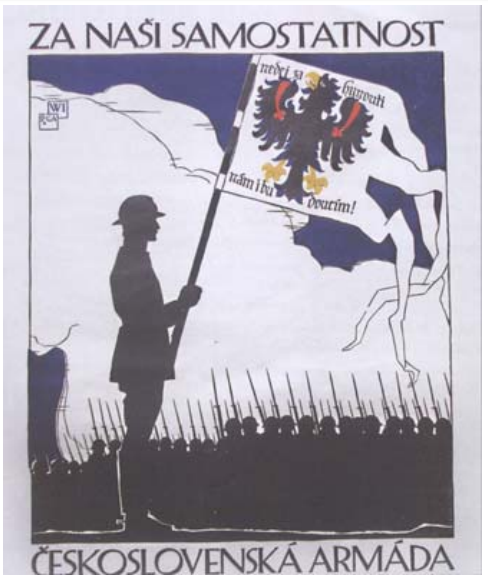

On the other hand, the four-star flag is missing on a poster with a title “Za naši samostatnost / Československá armáda” (For our independence / Czechoslovak army) where a soldier holds a white flag with the black eagle of St. Wenceslas (Fig. 10).

In April 1918 V. Preissig started to prepare a set of 16 recruiting postcards. Half of them contain the motifs from the posters, the rest have new motifs. Preissig preferred the four-star flag on most postcards. For example he changed the motif with the soldier carrying the white flag with the black eagle of St. Wenceslas, replacing it with the four-star flag (Fig. 11).

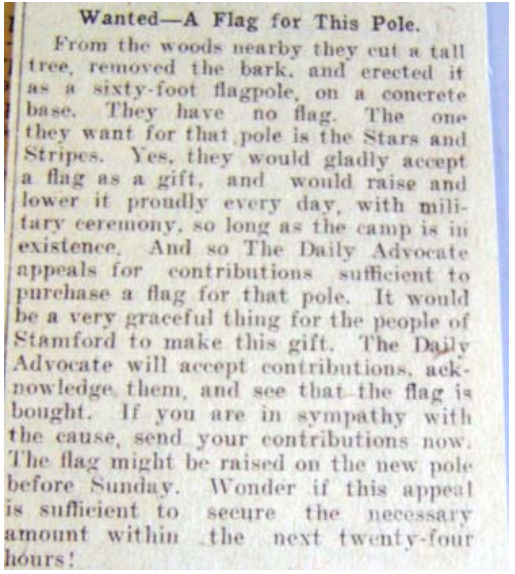

His four-star flag was so popular that it flew over the barracks in a military camp at Stamford, Connecticut. This camp, for Czech and Slovak volunteers before they were shipped to Europe, was built on grounds owned by the American sculptor Gutzon Borglum (he was famous for creating the monumental presidents’ heads at Mount Rushmore, South Dakota). At first even an American flag was missing in this camp. The situation changed after a local newspaper appearing in Stamford published an appeal for contributions to purchase a flag for a 60-foot flagpole in the camp (Fig. 12). (7)

A photo published in the New York Times of 30 June 1918 showed Borglum with his wife, children, and Czechoslovaks posing not only with an American flag, but also with the flag of France and the four-star flag (Fig. 13).

It is said that one four-star flag was made by Mary Montgomery Williams Borglum and donated to Czech soldiers who left America on 17 July 1918. However, many of the flags taken by volunteers to Europe were plain white-over-red (Fig. 14).

Sometimes we can see a tricolour of white over blue over red horizontal stripes, where the blue stripe was very narrow. Such a flag design, decorated with the arms of Moravia, Slovakia, Silesia, and Bohemia in the flag corners and with initials ČS in the centre of the flag, was made by countrywomen in America and given to volunteers (Fig. 15).

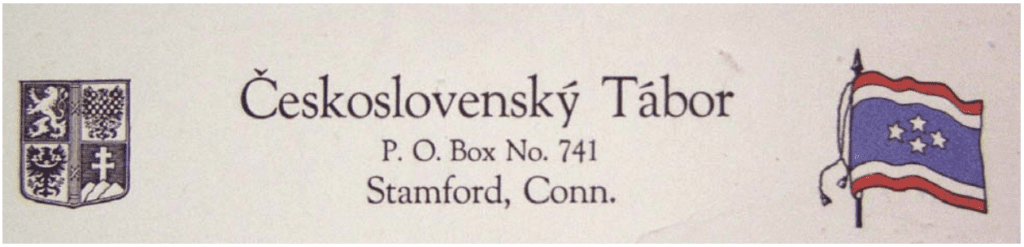

However, the four-star flag had a broader use; it appeared on a float and decorated also the heads of official letters sent from the camp in Stamford (Fig. 16).

On 24 July 1918 an article “Our revolutionary colours” written by Ivan Markovič, an influential Slovak politician and secretary of the Czechoslovak National Council in Paris, appeared in the official organ of CNC. (8) He wrote that the colours of the Czechoslovak revolution were white and red from its beginning and mentioned that white over red were used by Slovaks in the revolutionary year of 1848 before they changed these colours to white, blue, and red. František Kopecký from the Bureau of Military Affairs of the Czechoslovak National Council branch in America ordered the printing of a new set of postcards where the picture of the four-star flag was to be replaced with a plain white over red flag. Preissig did this in all postcards except one with heraldic flags and three four-star flags because he did not want to lower its aesthetic value (Fig. 17).

Olga Masaryková, the daughter of T. G. Masaryk, came to the U.S.A. in May 1918 to meet her father. She joined very quickly in the promotion of the Czech and Slovak nations. American journalists called her the “Bohemian Joan of Arc” thanks to her youthfulness and enthusiasm. In September 1918 she started to prepare a publication entitled The Czechoslovak Flag, to describe and depict symbols of a new-born country. Her father, like his secretary Ivan Markovič, was in favour of a white over red flag. He did not accept the arguments of his close friend, Herbert Adolphus Miller, at the time a professor of sociology Oberlin College (Oberlin, Ohio). Miller summarized his arguments in a letter of 4 September 1918 sent to Olga Masaryková: …One thing I want especially to urge upon you, is that you take the responsibility of trying to get an official flag. I had hoped that the one with the four stars had been adopted…this particular flag would be…easily remembered…I know you have a strong traditional feeling for the red and white but it has little distinction. The Poles have the same colors, and the city flag of Vienna is the same. One of the Cleveland librarians told me the other day that the children from the Bohemian district were all trying to get the postcards on which is this flag with the four stars. It seems to me that it is a proper feminine job to see that a flag, which is also beautiful, is adopted soon.”

The answer of Olga Masaryková was brief: “…As to the flag, I must tell you, that no one in exile or emigrated has any right to introduce a brand new flag without the sanction of the whole nation. We prefer our old simple flag to any local innovations….and “we are all just the servants on the inherited soil of our nation”, as one of our poems says. There is another by Havlíček …Our motto is honesty and strength, our colours red and white”. (9)

Olga Masaryková compiled three versions of texts for The Czechoslovak Flag. From a vexillological viewpoint, the biggest difference was in the description of the flag of the Czechoslovak National Council. This flag should be identical with the Czechoslovak flag and therefore Masaryková wrote: “The flag of the Czechoslovak National Council and its armies is white and red, the white forming the upper half of the flag. This is the ancient Bohemian flag which has also been adopted by the Slovaks in their revolution of 1848”. However, the second version changed the text on the flag of the Czechoslovak National Council in the following way: “Only the future Diet of the Czechoslovak State has the power to accept the official flag of the State. During this war the Czechoslovak National Council, the provisional government of the Czechoslovaks, has accepted as its official colors the white and red in blue field. On a white and red shield, placed horizontally on the flag, are the initials Č.S. worn also on the uniforms of the Czechoslovak armies in France and Italy. The blue field is accepted from the color of the three mountains Tatra, Matra, and Fatra on the Slovak coats of arms. Surmounting the staff of the flag are four interlaced rings, symbolizing the four component lands of the Czechoslovak State: Bohemia, Moravia, Silesia, Slovakia”.

Who was responsible for another flag design, suggested as the flag of the Czechoslovak National Council? We believe that this flag was designed by Štefánik, who was enthusiastic about uniforms and awards. He met with Masaryk in Washington on 17 September 1918 and showed him not only his designs for awards but also some flag designs (Fig. 18).

They could not be accepted because Masaryk preferred a white over red flag for the Czechoslovak flag. The compromise was to introduce one of his flag designs as the flag of the Czechoslovak National Council.

Štefánik’s favoured flag design was a little complicated because of the shape of the white over red shield. Olga Masaryková referred to it in one of her letters as a “dabbler” design. Before artist Joseph Růžička produced the final rendering for the publication (Fig. 19), he consulted with specialists in the Metropolitan Museum in New York on its description.

Olga Masaryková ordered a car flag in this design on 20 September 1918. It had to be displayed together with a white over red flag. Another order dealt with small black Hussite flags carrying a white chalice and long red Hussite flags displaying a white chalice on the obverse and inscription “Veritas Vincit” (The truth prevails) on the reverse and with white over red flags of wool and cotton.

All these flags were made in a workshop of a Slovak, Ján Janček, on Second Avenue in New York. Their first flag delivery reached the headquarters of the Czechoslovak National Council on 16th Street in Washington just in time on 18 October 1918. On that day, a declaration of independence known as the Washington Declaration was proclaimed and Masaryk and a colleague hoisted a white over red flag on the balcony of the headquarters. The large flags were made in the end of October. Instead of 5 x 6 ½ feet they were made in the same proportions as American flags (5 x 7 feet). This caused some problems with the Štefánik flag and therefore Ján Janček suggested changing the rounded cut to the straight one with the peak in the flying edge in the future.

According to a diary written by his assistant Ferdinand Písecký, M. R. Štefánik was working on a design of military awards and on a final version of a flag on the ship Korea Maru leaving San Francisco for Honolulu in late September and October 1918. After the ship with Štefánik and Písecký aboard reached Japan, on 5 November 1918 Písecký contracted with the flag company Iida & Co. in Yokohama for 1,533 copies of the Štefánik flag in different dimensions. They had to be little different from the drawings made in Washington. Unfortunately, only the text of the contract and not the drawings survived. (10) We learn from it that two flags were made from heavy silk with a gold fringe around. In addition, the linden trees (which do not appear in the picture in The Czechoslovak Flag) were “in gold thread, embroidery on both sides”. Most flags (1,000 copies) were 0.40 x 0.40 m. and some of them are now in Czech and Slovak museums (Fig. 20). (11)

The printing of the publication was as slow as the production of flags. R. Růžička sent the proof copies to Olga Masaryková on 29 October 1918 (a day after the proclamation of Czechoslovakia in Prague). We do not know if she read them immediately and, because the run of the publication was 5,000 copies, we can estimate that the Bartlett Orr Press on 8th Avenue in New York would have printed them, starting in October and finishing in November 1918.

Two months later an arms committee consisting of politicians, archivists, and heraldry specialists met in Prague. Their task was to determine the Czechoslovak symbols. They soon reached the same conclusion as Herbert Adolphus Miller. It was not possible to introduce the white over red flag for the Czechoslovak state flag because it was the same as that of Poland. Unfortunately, they did not consider the four-star flag by V. Preissig. After 15 months of discussions and negotiations another design for the Czechoslovak state flag was introduced: a white over red flag with a blue triangle extending to the half the length of the flag.

End Notes

- V. Vondrášek – F. Hanzlík: Krajané v USA a vznik ČSR. Praha 2009, p. 13.

- Za volnost naší drahé domoviny: příspěvek k dějinám hnutí za osvobození zemí čs. Chicago: 1921, p. 7.

- Z. Svoboda: Česká státní a vojenská symbolika. Praha 1996, p. 14.

- L. V. Prikryl: Prvá vlajka česko-slovenskej federácie? In: Vexilologie No. 94, p. 1832–1833.

- A. Brožek: Vexilologické aktivity Vojtěcha Preissiga. In: Vojtěch Preissig Pro Republiku! Praha 2008, p. 76.

- V. Zuberec: Milan Rastislav Štefánik. Praha 1990, p. 25.

- The Daily Advocate of 24 April 1918, p. 1–2.

- Československá samostatnost, No. 29, 24 July 1918, p. 3.

- All mentioned letters by H. A. Miller and Olga Masaryková are kept in the Archives of Masaryk Institute in Prague.

- I found a copy of this contract in the file F. Písecký in the Military Historical Archives of Prague.

- The Czech vexillologist Z. Svoboda, who worked in the Army Museum of Prague, remembers that he could display flags of Czechoslovak legionnaires in an exposition in 1968. After the Soviet occupation of Czechoslovakia started, his exposition had to be cancelled. Nowadays they recall the bravery of Czech and Slovaks fighting for independent Czechoslovakia.

Article Acknowledgments: The author of the above, Aleš Brožek, wishes to express his thanks to Michael Faul for having gone through the manuscript and for all his suggestions and corrections.

Aleš Brožek was born in 1952. He is one of the founders of the Czech Vexillological Society, its first secretary, and editor of Vexilologie (1972–1975, 1983 to the present). He is the author of Lexikon vlajek a znaků zemí světa (1998, 2003) and numerous articles on Czechoslovak municipal flags and the compiler of annual bibliographies of flag books and charts.

A very special thanks to Steven A. Knowlton, Head, Publications Committee of the North American Vexillological Association for permission to reprint this article here. Please make sure to learn more about the North American Vexillological Association by visiting their website.

Many people attribute Jaroslav Kursa (October 12, 1875 Blovice – June 12, 1950 Prague) to be the creator of the Czechoslovak state flag as we recognize it today. However, in the 1960s, academic painter Jaroslav Jareš considered himself the author of the flag. A similar flag was said to have been used by Czech-American Josef A. Knedlhans as early as 1918. So….

To see many more of the posters of Vojtěch Preissig, you will surely want to visit our post entitled, Czech America in the Struggle for Independent Czechoslovakia. Zanna also wrote quite an interesting post entitled The Origin and Evolution of the Czech Flag, which you will surely want to read as well. To learn more about the Czechs and Slovaks at Camp Borglum, you’ll also want to read A New Declaration of Independence. Finally, for more historical articles about early Czechs in America, visit our archives.

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.