While describing the American character in his essay, “What is an American?” Jean de Crevecoeur also defined the unifying forces of the Czechs who immigrated to America. He stated, “In this great American asylum the poor of Europe have by some means met together, and the consequence of various causes.” The Czech pioneer in Texas verified another opinion of Crevecoeur when the immigrant discovered America

the rewards of his industry follow[ed] with equal steps the progress of his labor. From involuntary idleness, servile dependence, penury and useless labor, he has passed to toils of a very different nature, rewarded by ample subsistence.

The Czechs were descendants of a Slavic people living in Bohemia, Moravia, and in parts of Austria, Hungary, and Poland since the 5th Century B.C. Surrounded by warring countries, the homeland’s position exposed the Czechs to invasion for centuries. Marauding Avars, Magyars, Mongols, Poles, Tartars, Huns, Romans, and Germans took advantage frequently of this position to impose economic, political, and religious restrictions upon the Czechs. Although invaders often destroyed or mutilated the Czech pattern of life, they only succeeded in uniting them.

By the end of the sixteenth century, Bohemia was the wealthiest country in Europe, only to lose its independence in 1620 during the Thirty Years War. Since Bohemia was one of the principal battlegrounds, the Czechs were subject to the Germanization of schools, government, and church. As a result, names were changed and books were destroyed. Executions, banishment, exile, and confiscation were enforced. For a century thereafter, Czechs kept their traditions alive only by the telling of stories inside their peasant huts.

Wars, however, were not the strongest force behind emigration. The people could endure the fighting, suffering, and hunger, but even in times of peace, everyday life was less than sustaining. The agriculturally oriented inhabitants struggled with the region’s unfavorable climate and poor soil, which was hard to farm and yielded small crops. A report, compiled by Frantisek Silar and translated from the Czech language by Calvin. C. Chervenka, summarizes best the lifestyle of the majority of Czechs:

Most of the farmers . . . were small farmers because the previously large estates had been subdivided into more and more parcels as the population had increased. Most of the residents were resigned to the small yields from their farm lands; for milk from their cows and goats; and for game and other items from the surrounding forest. Those who did not own any land lived in rented houses and worked for the others in the summers as day laborers. During the winter, they were weavers or prepared the flax for spinning and weaving.

Overcrowded conditions in one-room cottages were prevalent. Often two families would occupy a cottage, where the spinning wheel commanded the greatest portion of the space.

Although the oppression which followed the 1848 revolution in Austria-Hungary created heavy restrictions on the populace, the 1850 catastrophe produced the most insufferable conditions which ignited the Czechs’ interest in America. Fields failed to yield crops and people were selling their feather beds, furniture, and the least necessary items of clothing for money to buy food. For many, however, relief lay only in the venture of emigration to America. The endeavor was given long and serious consideration, as it would separate families and sever strong ties to the homeland. Regardless of the heartaches endured, the Czech pioneers were drawn to America with the hope of being free men and having an unhampered existence.

The first time Czech immigration to Texas arrived at Galveston in 1852, supplied with money to buy land and with the determination to stay. Because the crops in the Gulf Coast region matured earlier with less labor and greater yield, these early pioneers believed Texas offered better opportunities than any other state.

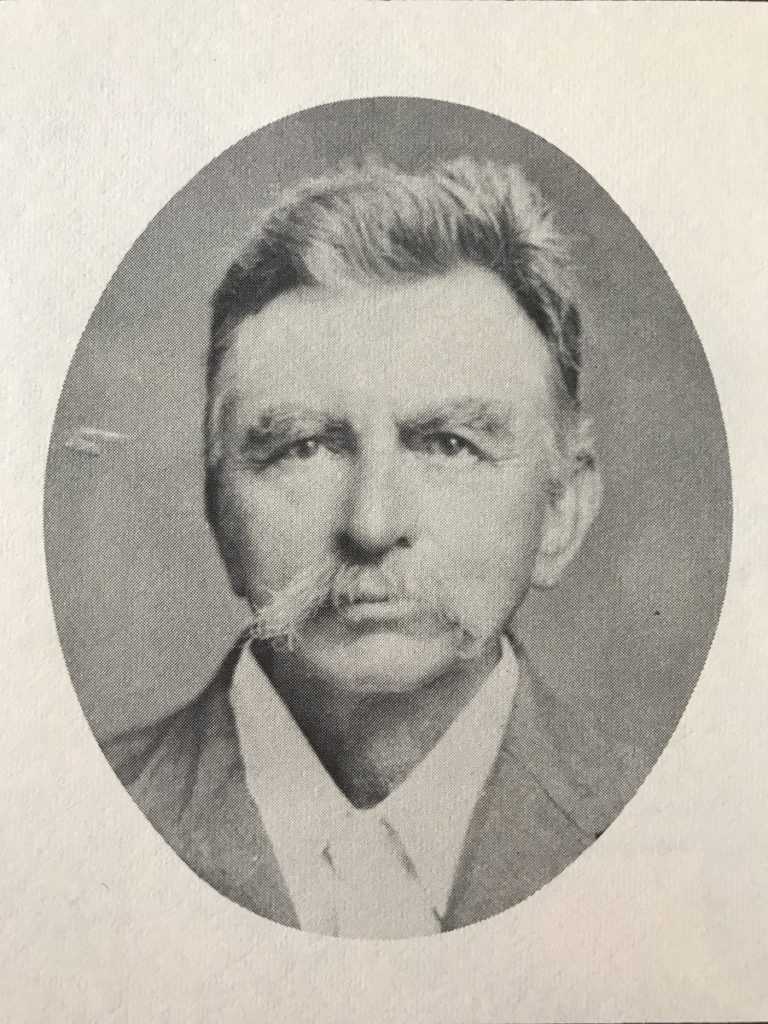

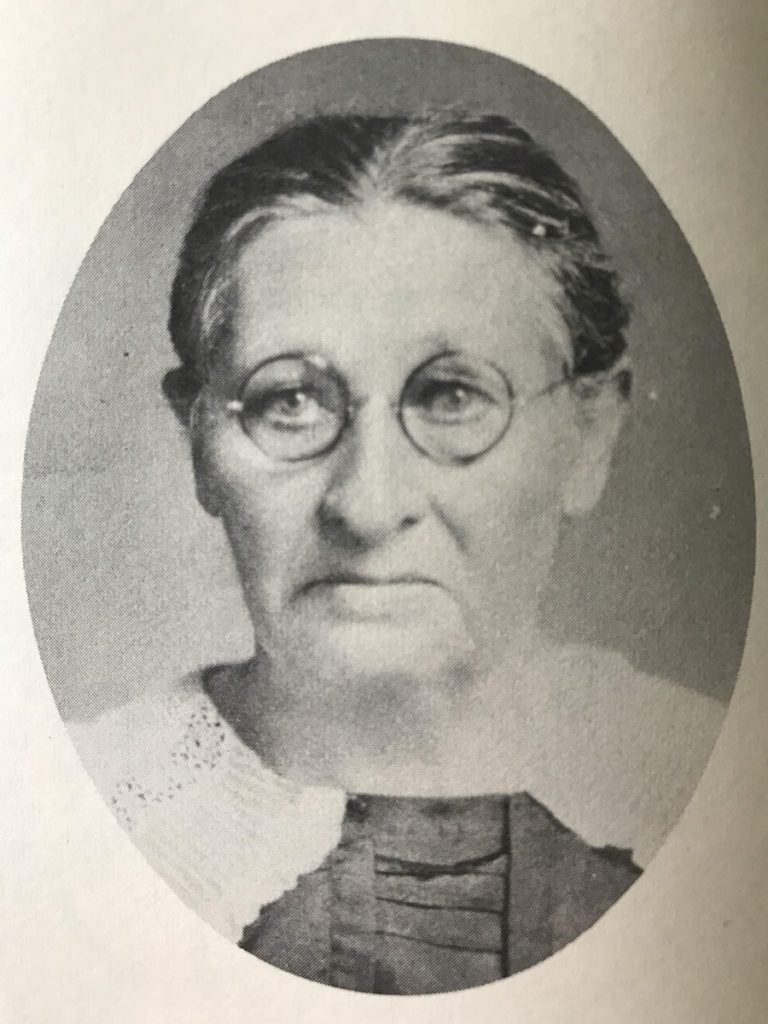

During the following twenty years, many Czechs immigrated to Texas. Among these were the families of Vince Lesikar and Katarina Reznicek. The Lesikar’s came from Cermenske, Cechach in Bohemia, and the Reznicek’s from Leskovec, Moravia. Both families fled the oppressing conditions of their homeland and were destined to meet on the fertile soil of Central Texas.

Jan and Rosalie Lesikar arrived in Texas in 1868. Lesikar was relatively poor and brought little more than a wooden box, which contained clothes, a few feather beds, and personal keepsakes. The voyage across the Atlantic Ocean in a sailing ship lasted several months, as a storm had blown the vessel far off course. The immigrants on board suffered intensely from seasickness. Fearing the ship would surely capsize in the heavy winds, they read their Bibles and sang songs to bolster their courage. A diet of bacon, beans, and wormy bread was brightened occasionally by homemade cheese, which was valued for the length of time it remained edible. While the food was less than nourishing, the scarceness of water loomed as a larger threat to their survival.

Vince Lesikar, only ten years old, was relieved when the ship reached Galveston. This city, the most important shipping port in Texas at the time, was a welcome sight for the entire group. From Galveston the immigrants traveled inland by ox-drawn wagons. Baggage and small children rode on the wagons, while adults and older children walked behind.

Jan Lesikar, Vince’s father, settled with his wife, five sons, and a daughter near Round Rock. Another daughter had died before they left Cermenske. For a brief period, the Lesikars farmed in Round Rock. Later they moved to Seaton Community in Bell County in order to be near other Czech families. Lesikar and his wife remained there until their death.

In Bell County the Lesikars traveled ten miles to Temple to buy some groceries and farm and cooking utensils. Since roads were few and no bridges spanned the creeks, they had to carve a path through the hills and undergrowth. With axes and grubbing hoes, they leveled the land to Temple. If the creek’s banks were too steep for the wagon, The Lesikars would dig until the banks were down and the wagon could cross. In wet weather traveling was unpredictable. If rain caused the creek to rise, the family would wait in Temple until conditions improved. They slept dry, if less than comfortable in their wagon. The round trip, a full day’s journey, was a welcome diversion from the tedious chores of the farm.

The Lesikars lived in a one-room, dirt floor log cabin, which was located near a stream. The stream served as the “washing machine” and the source of drinking water. Before they could cultivate the soil, the land had to be cleared of timber. Planting was a family affair. Lesikar and the older boys drove the mule and plow, while Mrs. Lesikar and the other children followed with sacks of seed.

Four years after the Lesikars departed for Texas an event occurred in Moravia which changed Katrina’s future and that of her family. One day a friend approached Pavel Reznicek and offered to loan him money to travel to America with a group of emigrants. There would be enough money for the Rezniceks until they landed in Galveston. Reznicek, who was a brick maker, saw little future for himself in Moravia, and therefore, he eagerly accepted the proposition.

In 1872 when Katrina was nine years old, the Rezniceks left for Texas aboard a steamship. During the voyage the immigrants suffered many hardships. Bread and dried fish were their main foods. Katrina often carried water to the seasick passenger. Because of stringent water rationing, the German crew grew suspicious of her frequent trips to the water tanks. Suspecting that she was using water illegally to wash her face, the officer questioned her. Katrina was too frightened to answer. Finally, a witness explained that the girl had been giving water only to others.

After surviving the rough voyage, the immigrants reached Galveston. A tall Negro man carried Katrina to the shore. This became an unforgettable experience for her as she had never seen a dark-skinned person before. She recalled this incident many times in later years. The Rezniceks brought with them a few clothes, personal keepsakes, and a deeply valued Bible, which had been buried for almost thirty years to protect it from Catholics. In the seventeenth century Ferdinand I of Austria made Catholicism the state religion of Bohemia. All protestant literature was seized and burned. Like many other Czech immigrants, the Rezniceks brought a strong religion with them, which later became the Lutheran faith in America.

On foot and in ox-drawn wagons, the Rezniceks left Galveston. After several days they arrived in Bell County, where the rich black land appealed to their inherent aptitude for husbandry and handicraft. Reznicek was quick to devise a plan to escape the scorching Texas mid-day heat. In the cool of early morning he plowed the fields, weeded crops, built split-rail fences, or picked the cotton. During the afternoons, he rested in the log cabin and returned to the fields in the early evening. While helping her husband with farm work, Mrs. Reznicek kept the younger children within her sight. After completing her work outside, she either cleaned the cabin’s floors or cooked supper. When the evening meal was finished, she began preparing food for the following day. Most nights she washed the clothes and hung them to dry in the cool breeze.

Each day the children awoke early to complete their chores. Katrina, who did not enjoy the early hour, milked the cows at sunrise. At night by moonlight they often helped pick cotton or cut timber to clear more land. Many nights the children sat before huge baskets of cotton and removed dirt and dried leaves from the fibers. After the cotton was harvested, it was taken in wagon to the mule gin. The children carried the cotton baskets into the gin and emptied them until there was a pile of cotton higher than their heads. When the baskets were emptied, the children watched the workers trample the cotton into the press from which processed cotton was made. The children were told that about three bales of cotton were processed at the gin each day.

Because Reznicek had to repay the money he had borrowed to come to Texas, the family lived with only the necessities. The log cabin’s floor was full of holes. Katrina often recalled that when she swept, there was no dirt under her broom by the time she reached the door. the mud, which was used to seal the walls, did little to stop the wind. Reznicek, however, encouraged his family to have patience, for he knew that they would have money after the debts were paid. Meanwhile, they slept on corn shuck beds, worked hard, and looked forward to the future.

Once a year the family traveled twenty miles to church. Using his carpenter skills, Reznicek provided a unique means for transporting his family to the annual religious gathering. From logs he made a slide, a type of sled usually used in snow, which he hitched to the ox team. On top of the slide, Mrs. Reznicek sat and nestled her youngest children close to her. With Reznicek and the older children walking beside the homemade vehicle, they left for the annual religious affair. Frequently small mishaps enlivened the trip. The most common incident resulted from the animals’ bounding toward the nearest water source. The unbalanced slide bounced the passengers badly and threw them off. With patience they watered the oxen, replaced the box on the slide, reloaded the disheveled passengers, and continued the trip. With daily perseverance, the Rezniceks reached their destination. Church was not only a time for worship but also a time for socializing. After holding services in someone’s house, the pioneers then gathered to exchange news with their distant neighbors.

In Bell County the Lesikars and Rezniceks lived a mile from eachother. Since the two pioneer families had so much in common, it was not surprising that Vince and Katrina should eventually meet and marry. When Vince proposed, he presented Katrina with a ring made from a dime. The occasion was special, but mostly in sentiment. Katrina’s best Sunday dress was her wedding gown. Since there was no church, they were married in a simple ceremony by an official, the equivalent of today’s justice of the peace.

After the wedding, the couple moved to Seaton Community and lived in a one-room log cabin with a dirt floor. Each of the four corners was occupied. The cotton seed for next year’s crop was in one corner, the salted meat and sausage were stored in another, the beds for the family were tucked into the next, and the ill-equipped kitchen was placed in the last. In the center of the room stood the eating table. Vince made a few of their pieces of furniture, but the chair of honor was an old apple box. When Vince came in from working in the field, each insisted that the other sit on the box.

The young Lesikars worked dilligently for their livlihood. They cured their own meat in a small smokehouse by hanging the salted pork and homemade sausage over smoke from rotten wood. Vince plowed the fields with mules as his father had done. Lesikar recalled that one day the mule suddenly stopped. The animal had seen a stump in the row, decided to take advantage of the situation, and rested. Lesikar lifted the plow over the stump and the two continued to work.

The Lesikars had been married several years when they sold their farm in Bell County and moved to West Texas. With their three children and the John Krizan family, who were close friends, the Lesikars departed in a covered wagon on the three-week journey. They traveled a distance of thirty miles each day. In West Texas they lived in a two-level dug-out on the hillside. One room was underground and the other was on ground level. Lesikar bought 320 acres of land at $1.35 per acre, but he never obtained a homestead because he did not remain there long enough.

Katrina did not like West Texas. The continual drought, windstorms and dust storms were unbearable. Even the chickens nearly lost their feathers because of the biting wind. There was no water except for what could be obtained from a windmill, and since there were no trees, the only source of fuel was dried cow dung. The pioneers often joked that they obtained their “water from the windmill and wood from the cow”.

After six months the Lesikars returned to Central Texas. In 1894 they bought farming land at South Elm Community in Milam County, where the area had favorable climatic conditions. Timber and water were abundant, and crops required little cultivation to yield rich returns. With the exception of the river bottoms, the whole area was free of malaria. Katrina lived in a house of sawed lumber. It had one room and an upstairs loft, and again Lesikar built the furniture, which included a bed, one bench, and a box for a chair. Homemade tallow candles were discarded in favor of kerosene lamps, and instead of cooking outside over an open fire, Katrina now cooked in the house on a wood-burning stove. She knew that Texas was indeed a land of opportunity to provide such a luxurious house.

Like their parents, the Lesikar children were industrious. They hunted to provide food and money. The young boys skinned raccoons, opossums, and skunks to sell the hides. Although the children attended South Elm and Elm Ridge schools only eight months of the year, they never missed except for illness. In those days, teachers considered the Lord’s Prayer and some reading, writing, and arithmetic all that were necessary for pioneer life. For the children, Christmas was a happy holiday. On a typical Christmas morning the young children received apples, oranges, candy, and a few firecrackers.

Although Katrina spoke and read Czech and could understand Polish, she never learned to speak English fluently. Vince, however, spoke Czech, German, and English well. Because their language had almost no affinity with that of their neighbors, the Czech families in Milam County clung together. Memories of their native country’s music, songs, festivals, and religious and national traditions generated a desire for their own church and priest. Eventually the Czech Moravian Bretheren Church was located at Buckholtz, where the Lesikar family attended regularly.

NOTE: Buckholts Brethren Church marker was erected in 2002, it is located at 606 N. 4th, Buckholts, TX 76518. As early as 1848, Bohemian and Moravian immigrants of the Unity of the Brethren faith arrived in Texas. The Protestant denomination began with Czech reformer John (Jan) Hus, and when Buckholts residents held their first Brethren services in 1894, they used the Czech language. The Rev. Adolph Chlumsky led the first services for the group, which in 1907 formally organized the Czech Moravian Church. Members built a wooden sanctuary at this site in 1913 and used it until dedicating a new structure in 1951, around which time the church began holding services in English. In 1959, the congregation changed its name to Buckholts Brethren Church. It continues to serve as a community focal point.

Katrina lived to enjoy her grandchildren and great-grandchildren. On September 27, 1954, she died at the age of ninety-one. Vince died at eighty-four on March 22, 1942.

Vince Lesikar lived in Milam County forty-eight years before he died; Katrina lived there more than sixty years. They witnessed the settling of Milam County by a large number of Czech families, such as those of Frank Marek, John Macha, and Frank Hejl near South Elm. Other Czech immigrants like the Motls, Dukatniks, Sefciks, Poborils, and Hruskas helped form the communities of Seaton, Ocker, Cyclone, and Zabickville in Bell County.

Through pride and a strong bond of unity, the Czechs preserved much of the culture of their homeland. Czech influence is evident statewide. The Czech language, still spoken in many Czech homes, is an academic course at Rogers High School, The University of Texas at Austin, and Temple Junior College. Czech music is kept alive by such groups as the Vrazel Polka Band, who can be heard each Sunday afternoon on KMIL radio station in Cameron.

Literature written in the Czech language is widely circulated, although some newspapers which once existed have ceased publication. The Vestnik, a monthly newspaper, is read nationally.

The Vestnik is a weekly membership newspaper whose name means "bulletin" in Czech. 2015 marked 103 years since Frank Fabian edited and published the first issue in Hallettsville. SPJST members believed then - just as now - in the necessity of effective and regular communication between all parts of the organization. In a very real way, the newspaper has been a builder of images and a shaper of opinions and attitudes about the fraternal activities, insurance, and other benefits available to members.Through two world wars, the Great Depression and decades of national and international tension and triumph, the Vestnik continues to evolve to reflect the changing needs and special concerns of SPJST members. On a weekly basis, the Vestnik delivers news on a wide range of organizational and cultural topics. In addition, each issue provides SPJST members with a forum for sharing news and information about happenings at their local lodges and youth clubs. More information is here.

The Svoboda, which means Liberty, and the Denni Hlasitel (Daily Caller), which was published in Chicago and circulated throughout the nation, were important to the Czech settlers. Texas farmers read the Texasky Rolnik, and Hospodar was a newspaper published in the form of a single magazine.

Anton Stiborik, a resident of Taylor was editor of Texasky Rolnik, a Czech language newspaper and at one time edited the Nasinec, a Czech paper at Granger. Source.

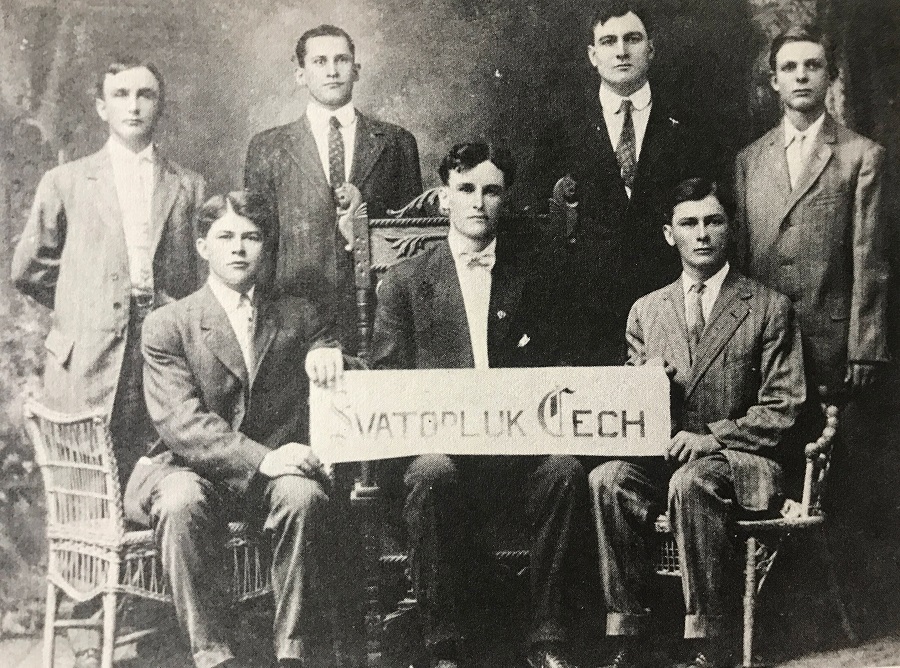

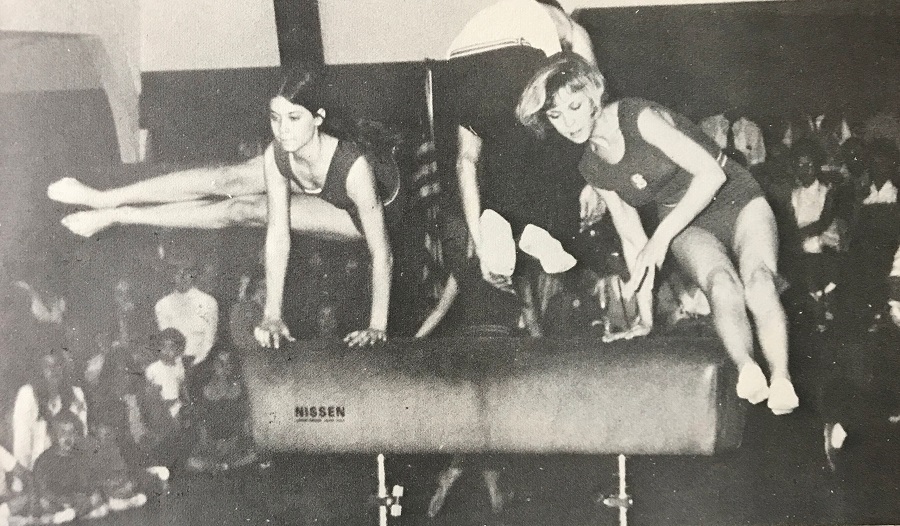

Organizations for social affairs, athletic training, and service for Czechs are found in Texas. One of the largest of the Czechoslovakian fraternal organizations in Texas is the Slovanksa Podporujici Jednota Statu Texasu (S.P.J.S.T.), also called the Slavonic Benevolent Association of the State of Texas. The Svatopluk Čech was a fraternal organization at Hill’s Business College. Sokol, a Czech athletic group, teaches the creed of sound bodies and clean morals. A Czech insurance company, RVOS, is the Farmer’s Mutual Protective Association of Texas, which also published a quarterly newspaper on current fire insurance information.

Czech settlers accepted possibilities and called them opportunities. Because their language differed from that of their neighbors, they worked to preserve their culture and unite their people.

If Texas is great today after a century of development, the large population of Texas-Czechs has helped to make it so.

This article was written by Cathy Jean Kubes from Yoe High School in Cameron, Texas and originally appeared in the Texas Historian periodical from November 1972. Obviously, as it is almost 50 years old, some of the information may be outdated. I did link to sources throughout above. At the time of this writing, the article also provided the following bibliography:

Books

- Jan Kohut and His Son Josef by Rudolf W. Cervenka, Waco, 1966.

- This Is America by Jean de Crevecoeur, New York, 1950. (Crèvecoeur (1735-1813) was a French native and came to the United States as a mapmaker then a farmer, and later served as a French consul. His essay, Letters from an American Farmer, describes a large picture of American life of the time.)

- Czech Pioneers of the Southwest by Estelle Hudson and Henry R. Maresh, Dallas, 1934.

- The Southwestern Historical Quarterly, by Henry R. Maresh, October 1946.

- Texas, A Guide to the Lone Star State by Texas State Highway Commission, Austin, 1940.

- The Handbook of Texas by Walter Prescott Webb, Austin, 1952.

Newspapers

- Temple Daily Telegram, March 25, 1942.

- Cameron Herald, September 30, 1954.

- Vestnik, January 1, 1969.

Unpublished Manuscripts

- Milam County from 1870 – 1900 by Mary Bell Batte, Cameron Public Library.

- Czech Histo-Genealogical Displays by Calvin C. Cervenka, Temple Junior College, Temple, Texas.

- The First Nepomuky and Cermna Emigrants in Texas by Calvin C. Cervenka (translated from a Czech report by Frantisek Silar) Temple Junior College Library, Temple, Texas.

Note: If anyone has an unpublished Czech historical manuscript, please contact me at sayhi@tresbohemes.com. Let’s publish it and share the information! I can make that happen. ;)

Records

Birth Certificate for Katrina Reznicek, Leskovec, Moravia, September 21, 1863, in possession of Mary Lesikar.

Interviews

- Mary Lesikar to Cathy Kubes, November 6, 1971 and January 23, 1972.

- Vince Lesikar to Cathy Kubes, January 3, 1972 and February 13, 1972.

- Mr. and Mrs. Ladis Kaplka to Cathy Kubes, November 7, 1971 and January 27, 1972.

- Calvin C. Cervenka to Cathy Kubes, February 8, 1972.

We work to excite you about your Czech heritage by sharing information you would likely not come by on your own. Oftentimes we purchase such articles at top dollar just to share them with you.

* * * * *

Thank you in advance for your support…

You could spend hours, days, weeks, and months finding some of this information. On this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

We appreciate you more than you know!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.