Czech and Slovak cinema is finally beginning to make an appearance on the world stage. Among the most successful Czech films made after the fall of communism are: Kolya, Divided We Fall, Cosy Dens, Loners, I Served the King of England and Walking Too Fast. The first Czech CGI animated movie was The GOAT Store – The Old Prague Legends in 2008. But movies prior to the fall of the iron curtain were incredibly artistic treasures which should be revisited. Kinoeye was an online journal of European film published between 2001 and 2004, and prior to that it was a column in Central Europe Review. They are no longer publishing. Today I am sharing an article from approx. 15 years ago which I discovered from Kinoeye. I’m happy to be able to preserve it here and share it with you today. It was written by Andrew James Horton, the Editor-in-Chief of Kinoeye:

For such a small country, the Czech Republic’s cinematic clout has been relatively large on the international scene. Czechoslovakia (which existed from 1918 to 1992 before the country split into the Czech Republic and Slovakia) won two Oscars in the 1960s and the Czech Republic has had a further win at the Academy Awards in the 1990s – and that’s just the tip of the acclaim.

Like all central European countries, the Czech and Slovak republics have been buffeted around by the whims of history, as borders have flown back and forth and regimes have come and gone. Any journey into these countries’ cinematic cultures, then, is inevitably also an exploration of their complex histories and senses of identity. But don’t be put off!

Compared to neighbors Hungary and Poland, the republics have produced far lighter screen fare, with plenty of delicate humor, even as they explore (or were made in) some of the countries’ darkest moments. Moreover, both national cinemas have been strong on drawing on universal themes and, while a knowledge of either country’s past will add another level of understanding, it is not at all necessary to have a PhD in European history to enjoy these works.

The Czech New Wave

Boasting some of the most attractive films produced in the Europe of the 60s, the Czech New Wave is the “golden era” in the country’s distinguished cinematic history and the obvious starting point for anyone wanting to learn more about Czech film. The Czech New Wave is usually defined as by a relatively small group of directors, including Miloš Forman, Jirí Menzel, Vera Chytilová, Jaromír Jireš and Ivan Passer, who made their debuts in or around 1963 and continued to produce internationally acclaimed work through most of the rest of the decade.

However, there was no manifesto or theoretical writings that the group, which was never a formal one, drew on, and it’s hard to pin the Wave down to any one style: works of playful observation, visual poetry, biting sarcasm, gentle humanism, mocking absurdism, tender eroticism and formal experimentalism count among the films by the Wave’s directors.

French New Wave films were associated with an interest in American cinema, a rough-and-ready aesthetic, long takes and cinematic self-referentiality. By contrast, the Czech New Wave was inspired more by Czech literature, generally sought a more polished style, used either classic shot lengths or experimental montages with very rapid cutting and showed little interest in cheekily borrowing from film classics. In fact, there was some animosity between the two waves, and Jean-Luc Godard was particularly scathing, describing Czech cinema of the time as being “bourgeois.” What the waves of both countries shared in common was an interest in a natural, less studio-bound cinema that focused on real people and captured their concerns.

Although the New Wave is associated with liberal humanism and Czechoslovakia is famous for its 1960s experiment in “socialism with a human face” during the Prague Spring of 1968, there was little overlap between the two phenomena. Few of the films commonly associated with the Wave were made in the short spell (just over eight months) of political liberalism, and by then the wave had largely peaked and international interest in it was declining.

If the Prague Spring didn’t define the group’s beginnings or development, it certainly defined the group’s end. Disturbed by the country’s new-found liberal direction and worried it might turn to the West, Russia led the Warsaw Pact countries in an invasion of Czechoslovakia and harsh reversals of the reformist measures were enacted (a process called “Normalization”).

In cinema, artistic creativity was clamped down upon and some directors were unable to make films (Evald Schorm), some left the country (Forman, Passer, Jan Nemec) and some had to compromise their artistic freedom to stay in the business (Menzel). The events of 1968 were obviously completely out of bounds for filmmakers, and if you want to brush up on the historical background and the personal pain the geopolitics caused, you have to look to literature: Milan Kundera’s novel The Unbearable Lightness of Being is not only one of the most popular literary renderings of this tempestuous period, but it was turned into a Hollywood film, with a relatively high degree of sensitivity, by Philip Kaufman in 1988 (New Waver Nemec was an advisor to the production).

A few films that had been planned before the invasion were able to be made before the new regime cracked down on the cinema industry, but these were banned and remained unseen until the late 1980s when the final, fatal cracks in Communism started to appear. Included in this group is Jireš’s The Joke (Zert), whose screenplay by Milan Kundera would form the basis for Kundera’s first novel. (Kundera, in case you wonder why his name keeps cropping up, taught literature at Prague’s film school FAMU in the 1960s and was close to many of the directors.)

In the 1990s, the New Wave directors were free to make films again, but none managed to make a work that rivalled their 1960s work, and only Karel Kachyna and Nemec came even remotely close. However, a new, younger group of directors drew inspiration from these classic films and were able, once again, to win international acclaim for Czech film.

The Beginnings

In fact, the groundwork for the Wave was laid before 1963 by a group of older directors in the 1950s that included Otakar Vávra, Vojtech Jasný, Karel Kachyna, Elmar Klos, Ján Kádar and František Vlácil. The stodgy propagandistic nature of Stalinist cinema gradually gave way and, by the end of the 1950s, a lighter, more human touch was apparent in films that focused on ordinary people more than they did on ideology and had more visual poetry.

Occurring before Czech cinema’s great 1960s breakthrough onto the world cinema scene, these works have remained much less known internationally, and only one of them, The White Dove (Holubice, 1960) by Vlácil, is currently available on DVD in the US. However, its interest in young people and their everyday problems makes it a worthy precursor, and it is also distinguished for its striking visual style (Vlácil studied art history at university) and economical narrative. The simple plot charts the healing effect the beautiful bird of the title, which has been blown off course during a race and landed in Prague, has on a cynical artist and a young boy who has suffered bullying and lost his confidence to play. The bitterness and isolation of the suffering main characters is an allusion to the effect totalitarianism has on the national and individual psyches, while the rejuvenating white dove is even more allegorical. However, the film can easily be enjoyed without having to subject it to a historico-political analysis.

Miloš Forman, Ivan Passer and Jaroslav Papoušek

The most famous of the Wave’s directors is Forman. His light, spontaneous filming style, with plenty of character observation and the use of lyricism and humor have made him one of the endearing personalities of the Wave. Undoubtledly, knowledge of his fine Czech works is also boosted by a dazzling career in America, where he has directed such hits as One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest (1975), Amadeus (1984) and The People vs. Larry Flynt (1996), the first two of which won multiple Oscars, including Best Director for Forman.

Throughout his Czech career, he worked with two important collaborators on his screenplays, Ivan Passer and Jaroslav Papoušek, both of whom would become directors in their own right (although only Passer would have an international success).

As with many of the Wave’s directors, Forman started out by highlighting the problems of ordinary people who have little interest in ideology and preoccupied by more personal issues. As Forman himself put it, he wanted to capture “the life problems, joys and sorrows of those people who had no chance of becoming a [Yuri] Gagarin…” (quoted in Peter Hames’s The Czechoslovak New Wave). Forman actually goes further than this, and many of his characters not only fail to be heroes but they are also losers who fail to fit into the mold provided by society. To better represent these people and to give his films more freshness, he relied in part on non-actors playing themselves and used improvisation.

Although this may seem a typical New Wave approach, Forman and his collaborators were actually unusual among the Czech New Wave, who more typically preferred professional actors over amateurs, scripts over serendipity and visual stylisation over capturing natural reality. Perhaps this difference is due to the fact that, of Forman, Passer nor Papoušek, none of them graduated in directing from FAMU. Forman was initially closer to theatre than cinema and graduated in screenwriting from FAMU.

After co-scripting some films and working as an assistant director in the 1950s, Forman made his own shorts in the 1960s. Competition (Konkurs, 1963) used cinéma vérité to capture a talent contest (a device that was directly lifted for his first American film, Taking Off, 1971.)

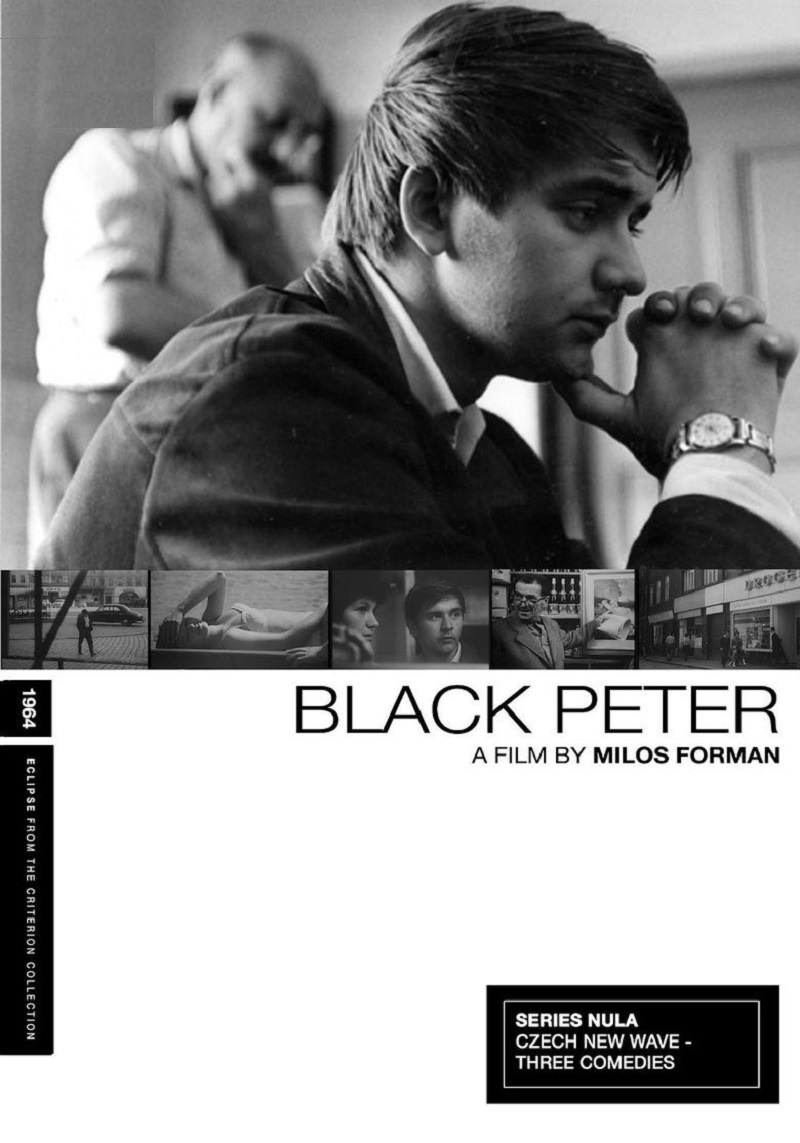

His feature debut Black Peter (Cerny Petr, 1963) was about a young who leaves school and starts work as a store detective after being bullied into it by his father. Meanwhile, the boy is making his first awkward moves in establishing a relationship with a girl. Black Peter (which is rather more imaginatively translated on the DVD itself as “Black Sheep”) shares its young protagonist’s political apathy. But the film also contains a direct parody of the justification that the communists used for having a secret police force (“Of course we trust the people, but we have to check…”). Black Peterwas a sensation in Czechoslovakia, and was entered into competition at the Locarno Film Festival, where it beat films by Godard and Antonioni.

Loves of a Blonde (Lásky jedné plavovlásky, 1965), his second feature, was more ambitious and contained more social criticism. The action starts in a remote town in which, due to an unforeseen consequence of socialist planning, women vastly outnumber men. The arrival of a unit of ageing army reservists to balance the genders leads only to disappointment among the town’s women, who had hoped for far younger males. Amongst all this, beautiful young Andula, the blonde of the film’s title, dreams of getting married. After being taken advantage of by the piano player in a visiting band, Andula reads in rather more to the musician’s commitment than he intended and turns up on his doorstep in Prague, much to the shock of the young man’s parents.

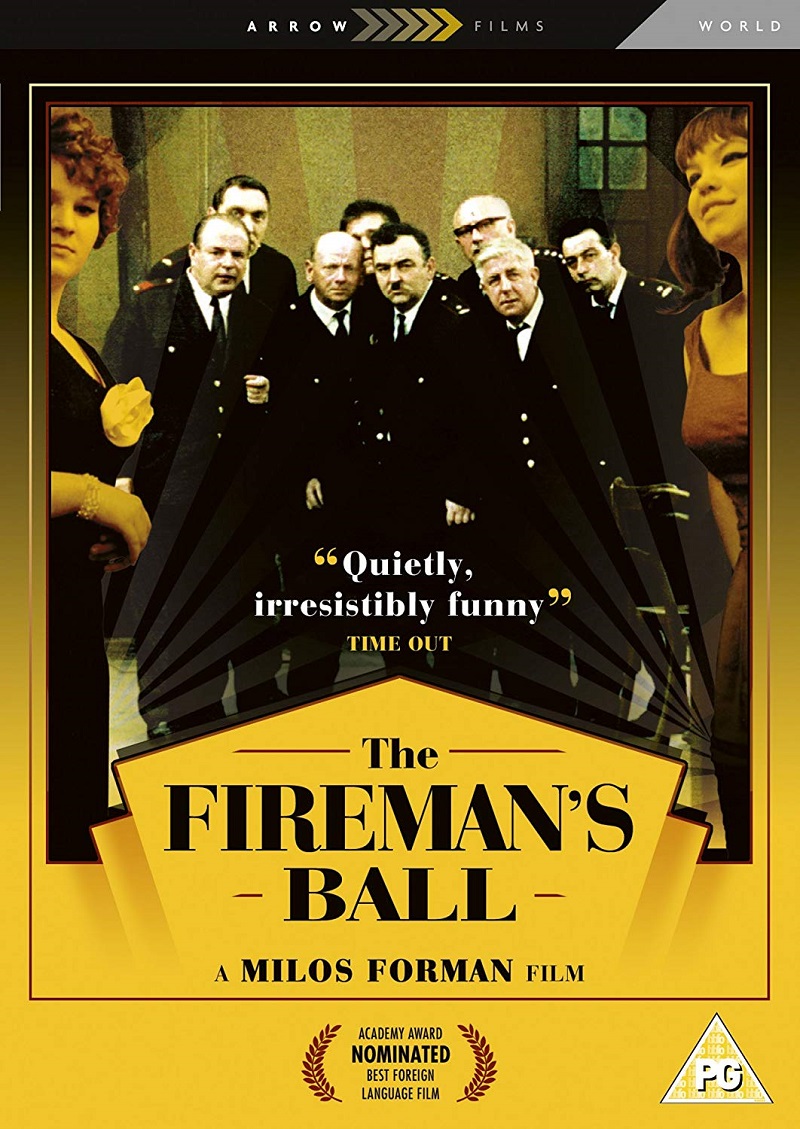

For his third feature, The Fireman’s Ball (Horí, má panenko, 1967), he was able to bring in Italian producer Carlo Ponti to raise enough money to shoot in color. If Loves of a Blonde had biting social and political criticism lurking beneath its tender, lyrical surface, in The Fireman’s Ball, it was out in the open. The event of the title takes place to honor a retiring fire chief who is dying of cancer. During the evening, the organisational bungling of the firemen becomes evermore apparent while the guests steal all the prizes in a raffle. By the end of the evening, only the fire chief has any remaining decency.

Despite Forman’s comic touch and his sensitivity with the actors (most of whom were actual firemen), the film is often perceived as highly pessimistic, and Forman’s romp had a troubled reception at the time. Carlo Ponti so despised the film that he demanded his dollars back, and Forman claims he almost ended up in jail. Forman’s bacon was only saved by a cloak-and-dagger operation to first steal a print of the film (carried out by fellow New Waver Jan Nemec) and then smuggle it out of the country for a special screening for François Truffaut and Claude Berri, who decided to buy the distribution rights.

Although The Fireman’s Ball had a negative reception in America at the time, the film turned out to be Forman’s ticket to the US and, in 1967, he went to New York to make a feature. While he was there, the invasion of Czechoslovakia began and he simply decided it would be better not to go back, thus commencing a whole new phase to his career. The rest, as they say, is history.

In a movement in which sensitive observation of the minutiae of everyday life was key, Ivan Passer made what is probably the most delicate portrait piece of them all, Intimate Lighting (Intimní osvetlení, 1965). So gentle is the film there is barely a storyline to distract us from the humorous depiction of two musician friends who meet up over a weekend in the countryside. Like Forman, Passer would resume his career in the US. Just as Forman changed direction and moved towards literary adaptations when in America, Passer’s Forman-esque observational style would largely be replaced by dramatic narrative, as in films such as Born to Win (1971), Law and Disorder (1974) and Cutter’s Way (1981).

Jirí Menzel and Bohumil Hrabal

One of the defining works of the Czech New Wave (although not necessarily one of the best) was the portmanteau film Pearls from the Deep (Perlicky na dne, 1965). Not only did it bring five key directors of the Wave (Chytilová, Jireš, Menzel, Nemec and Schorm) together in one film, making it the Wave’s official “coming out” as a group, but it tied them to a writer, Bohumil Hrabal, whose ability to capture the rhythms and refrains of everyday spoken Czech was highly influential on the Wave’s direction.

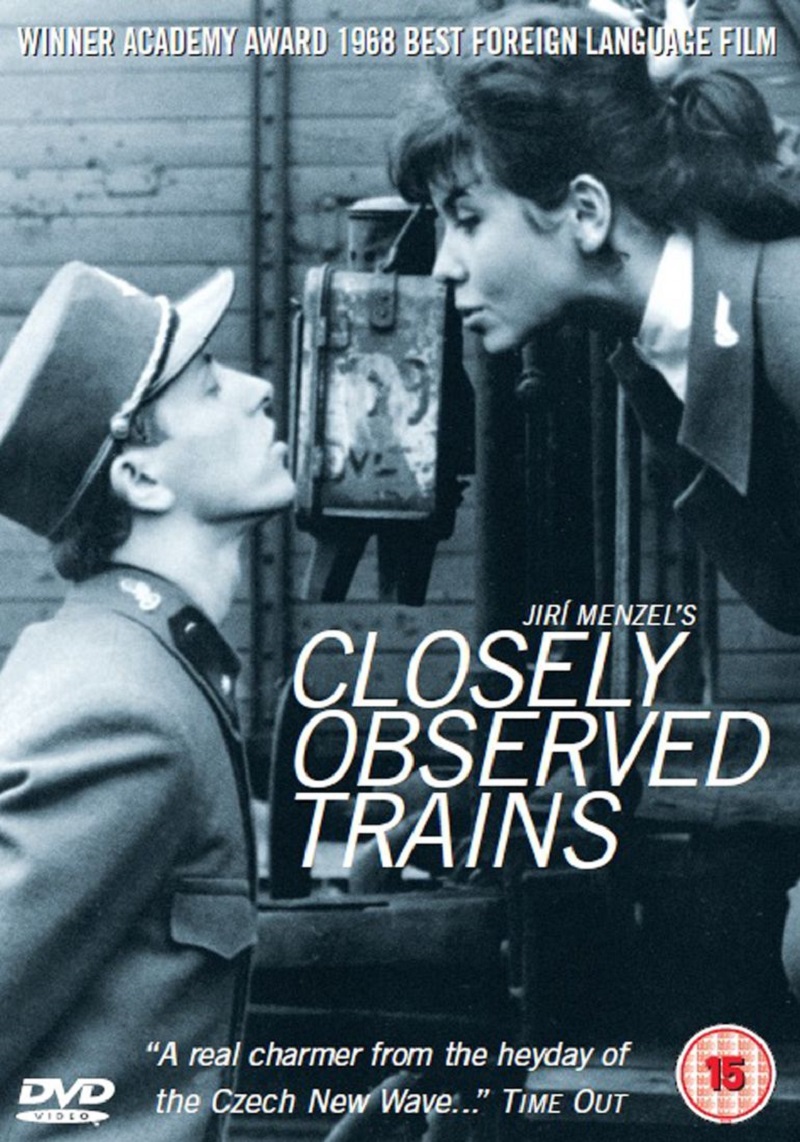

Of the 1960s reworkings of novels for the screen, by far the most successful was Menzel’s Oscar-winning Closely Observed Trains (Ostre sledované vlaky, 1966), based on a novel of the same name by Hrabal, who worked with Menzel on the screenplay. As is typical for New Wave films, the main protagonist is an awkward young loser with more interest in a personal problem than with the more momentous political events around him. The loser in question is Miloš, a new station assistant on a line feeding the German Eastern front in the Second World War. Despite wearing a German railway coat, Miloš has little time for worrying about ideology and is instead preoccupied with how to lose his virginity; and he hopes joining the Czech Resistance will help him do just that.

Like many central European films (before and after the 1960s), Closely Observed Trains probes the apparently unreconcilable relationships between the individual and the forces of history, heroism and happiness. Mocking of authority and worshipful of the mundane, the film was instantly popular.

Whilst other directors have adapted the books of Hrabal, and Menzel has adapted work by other authors, the pairing of the two together has been a magical combination. Menzel would go on to adapt three more Hrabal novels, but attempts to direct a further one in the 1990s became his undoing. Menzel was promised he could direct the film by Jirí Sirotek, the producer holding the rights, but after a complicated fiasco that wound up in court, the rights had to be sold, and the wunderkind of the Czech 1990s film scene, Jan Hrebejk, was chosen as the new director.

Menzel was so furious that he beat Sirotek with a stick in public at the Karlovy Vary Film Festival in 1998. Overall, the Czech public approved, and Menzel was even able to sell the stick at an auction. Menzel, sick of the whole film business, has largely retreated to work in the theater. Only his work as an actor (he’s famous for playing nerds) and directing a ten-minute segment of Ten Minutes Older: The Cello (2002) have kept him in contact with the world of cinema.

Vera Chytilová

Given that many of the New Wave directors were interested in the sexual awakening of teenagers and most of these filmmakers were men, there’s an unfortunate aspect of male voyeurism to some of the Wave’s films. The oeuvre of Vera Chytilová provides a radical counterbalance to this, and she has been called a feminist (although she rejects the label).

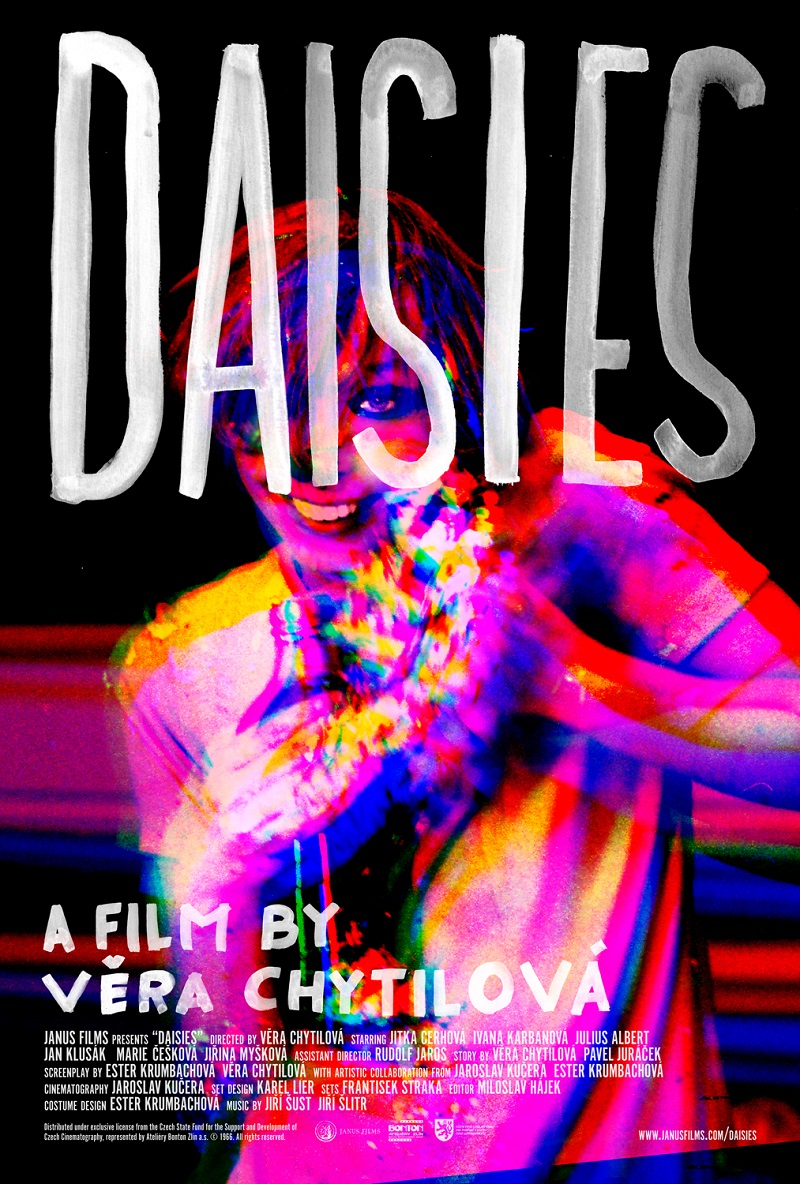

Vera Chytilová’s Daisies (Sedmikrásky, 1966) is the boldest and most innovative film of her career, and also the most demanding. The “plot” (if you can call it that) follows two “spoiled” teenaged girls, both called Marie. They get their kicks from leading on older men, accepting their generous hospitality and then cruelly rejecting them. Society has no room for such free spirits, though, and the girls get their comeuppance. The film presents itself as an anti-nihilist film, berating the selfish and destructive nature of the two girls and the general apathy of youth, but this is almost certainly a cover to allow Chytilová to attack societies (communist and democratic) which stifle individuality through patriarchy.

Although episodic in its narrative (“gibberish” to its detractors) and avant-garde in its filming techniques, Daisies is full of humor, wry observation and remarkable color photography (by Ester Krumbachová, one of the great talents of the Wave). Daisies, for all its impenetrable melange of symbols, is a surprisingly light-hearted and watchable film for a work that is so extreme in its experimentation.

Chytilová’s reputation in the West rests exclusively on Daisies. But she is still active in filmmaking and, throughout the four decades and the many political atmospheres in which she has worked, her films have remained consistently outspoken, controversial and topical (she was one of the first directors to make a film about AIDS, in 1988). And while she was perpetually in trouble with the authorities during the Communist years, it is hard to imagine that her films would ever be easily accepted by the establishment, even in a democracy. Indeed, the shooting of Expulsion from Paradise (Vyhnání z ráje, 2000) landed her in a German prison for a spell, when the authorities there detained her and some of her crew on suspicion of creating child pornography: the film’s action takes place in a nudist colony.

The New Wave and the Holocaust

Steven Spielberg’s Schindler’s List (1993) is rightly credited with starting a mania for films about the Holocaust. But it shouldn’t be assumed that none were made before that. Central European cinema has a long, albeit not continuous, track record in depicting the Holocaust and the traumas it caused in survivors on celluloid. This shouldn’t be surprising, as the Holocaust took place in central Europe and before the Second World War there were large populations of Jews in these countries that played an active part in creating the country’s cultural scene. Franz Kafka, for example, was a German Jew living in Prague.

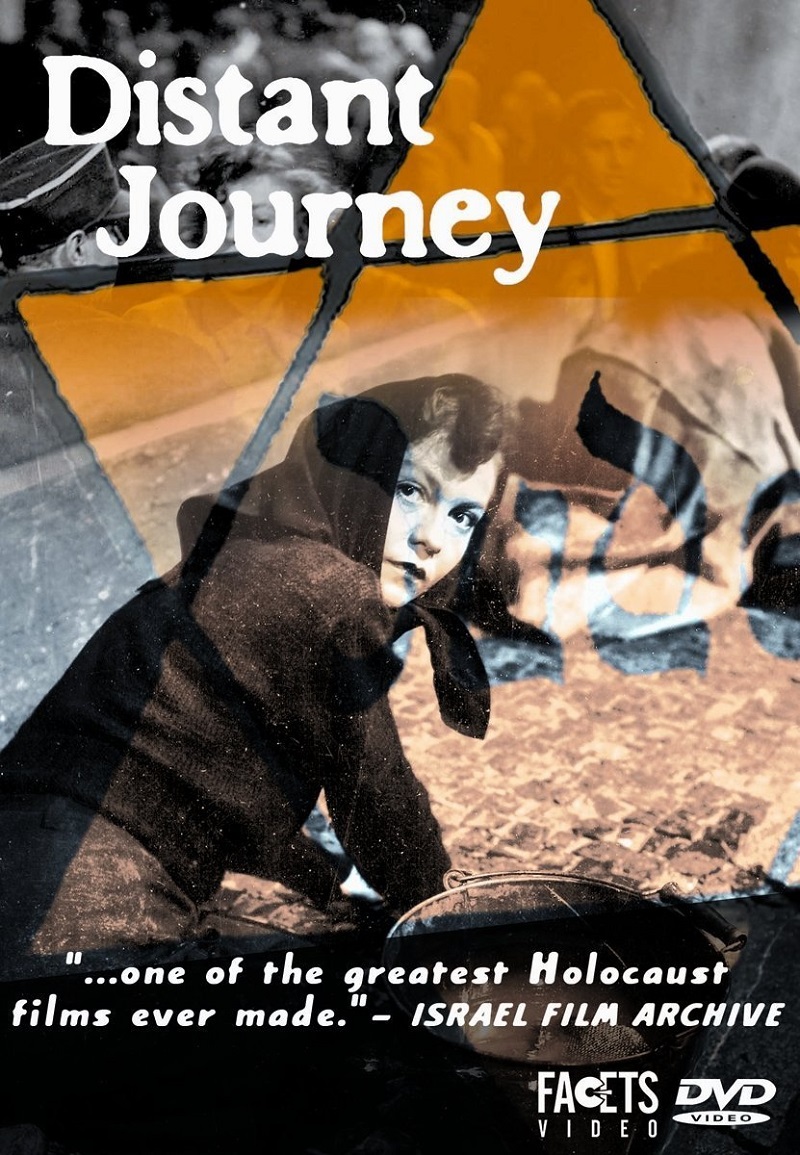

In Czechoslovakia, the first Holocaust film Daleká cesta (The Long Journey) was made in 1949 by Alfréd Radok. Radok was part Jewish and was transported to Poland during the war but managed to escape. Many members of his family, however, perished in the concentration camps, including at Terezín (Thereisenstadt) which is located near Prague and is where the action of Daleká cesta takes place. Radok was highly influenced by Orson Welles’s Citizen Kane (1941) and, like Welles, he made a visually strong debut by teaming up with an experienced cinematographer.

Although the film was banned for many years, it became a classic of Czech cinema and was championed during the period when it was unavailable by, among others, future president Václav Havel. Radok found it hard to work in cinema after that, but his work in theatre was a key inspiration for the Czech New Wave (Miloš Forman, for example, worked with him in his early days).

The films of the 1960s were often predicated on re-examining Czech history and exposing flaws in Czech national thinking. The Second World War, still prominent in the memory of the country, was a popular period to focus on, and Holocaust cinema flourished just as the subject was being broached in literature (interest in the work of Italian writer Primo Levi started in 1958, for example).

In Czechoslovakia, the writings of Arnošt Lustig were of particular importance, with four feature adaptations of his work: Zbynek Brynych’s Transport from Paradise (Transport z ráje, 1962), Jan Nemec’s Diamonds of the Night (document noci, 1963), Antonín Moskalyk’s Dita Saxová(1967) and Jirí Adamira’s A Prayer for Katherine Horowitz (Modlitba pro Katerinu Horovitzovou, 1969, released 1990).

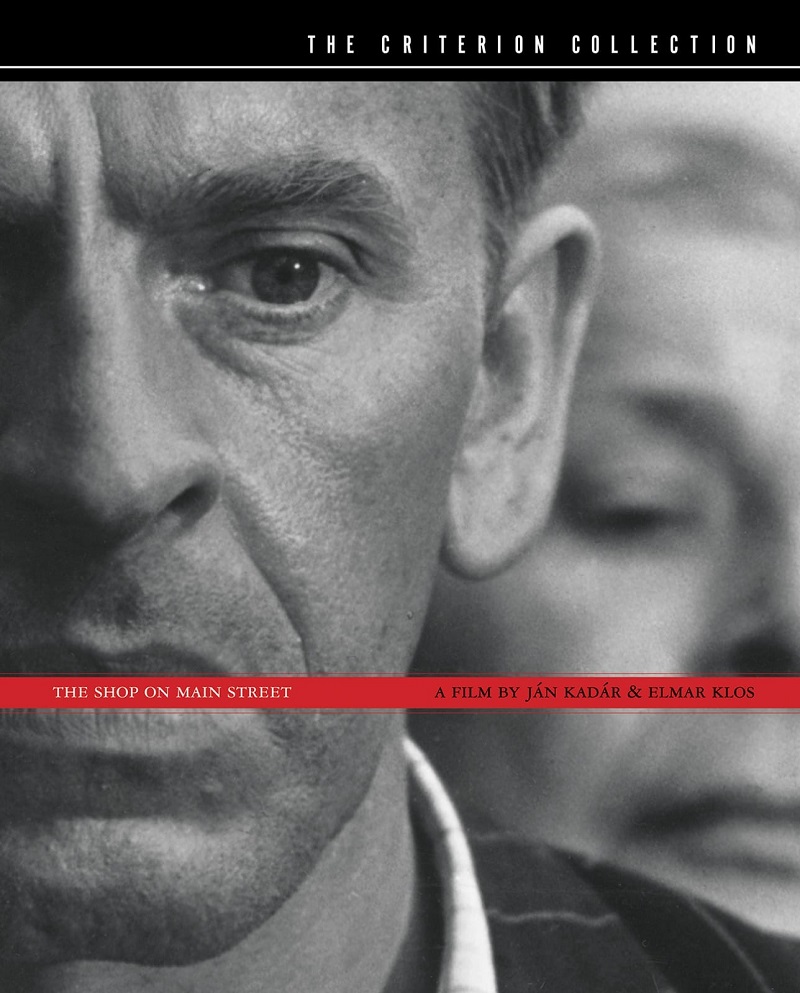

The most famous Holocaust film from Czechoslovakia, though, is Elmar Klos and Ján Kádar’s Oscar-winning The Shop on Main Street (Obchod na korze, 1965), rightly noted for sensitively combining humor and terror in depicting the deportation of the Jews from Slovakia to Poland and the indecisiveness of those who watched it happen.

The film centers on a hapless loser, Tono Brtko, who is bullied by his materialistic wife into taking over control of a shop when Jewish businesses are “Rand.” Reluctant to carry out his role, he watches with bafflement as the anti-Semitic mood increases before finally finding the courage to act, with tragic consequences.

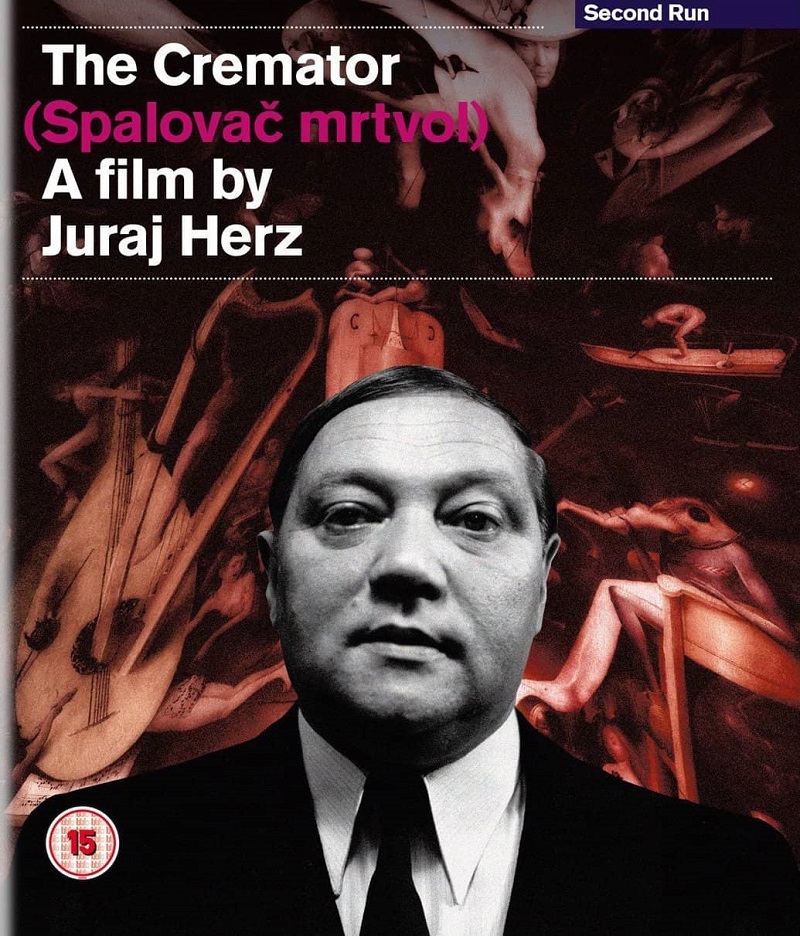

Two notable Czechoslovak films, both by Slovaks, directly confront the Final Solution: Peter Solan’s The Boxer and Death (Boxer a smrt, 1963) and Ravensbrück survivor Juraj Herz’s grotesque cult classic The Cremator (Spalovac mrtvol, 1968).

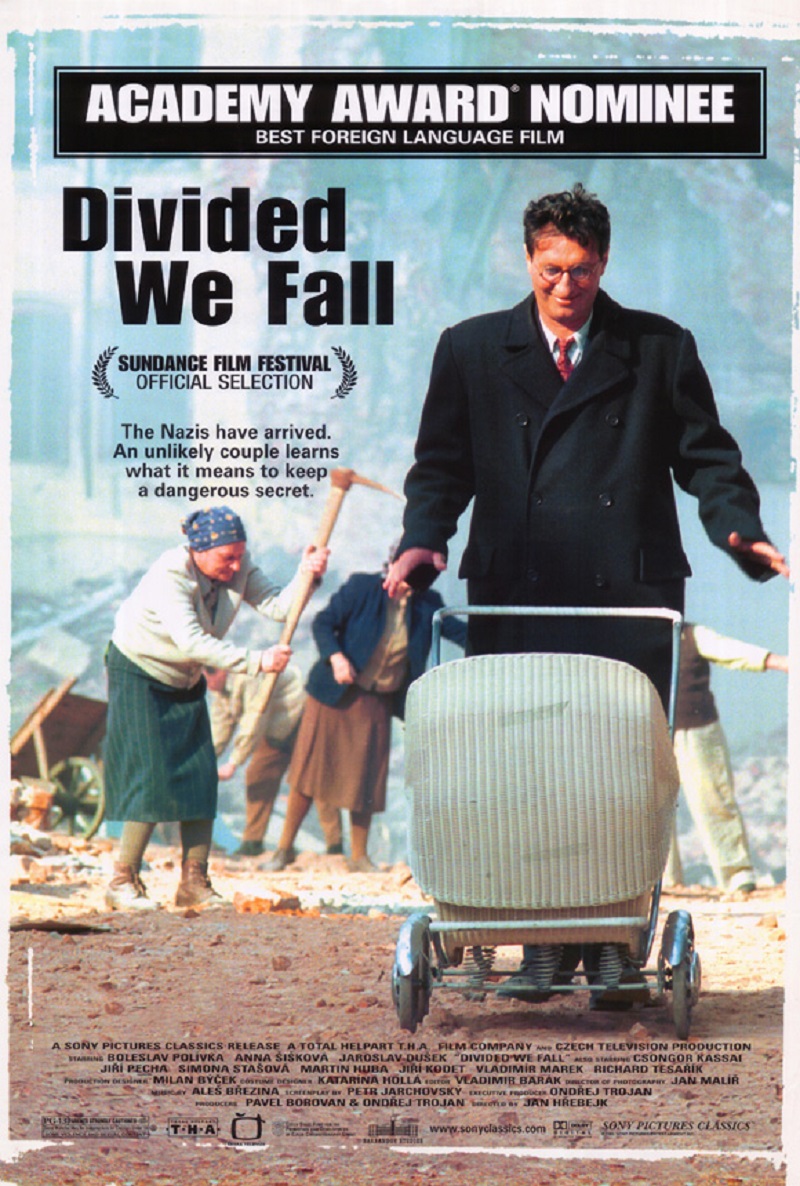

Hardly any Holocaust films appeared in the period of “Normalization” after 1968. (One of the few was Juraj Herz’s Zastihla me noc [Night Caught up with Me, 1986] which Spielberg directly quotes in his Schindler’s List.) However, the fall of communism allowed the subject to resurface and in the early 2000s films exploring the Holocaust and the Czech Republic’s Jewish heritage in general became quite popular with directors. The most notable example is the Oscar nominee Divided We Fall (Musíme si pomáhat, 2000) by Jan Hrebejk.

More than just a tear-jerking story about the war (as is Slovak director Matej Minác’s All My Loved Ones [Vsichni moji blízcí, 2000]), Divided We Fall explores acute moral and philosophical issues about national identity and the acceptance of outsiders (and the film was released at a time when the EU was criticizing the country for its poor race relations). With its re-examination of the past as a guise for making a comment on the present, a loser Everyman as the lead character and its warm and humanist sense of humor to buoy it along, Divided We Fall is a worthy successor to the New Wave’s mantle.

After the Prague Spring

The Russian tanks rolled into Prague in August 1968, and the country was cowed into toeing Moscow’s political line. Funnily enough, the definitive end to the Prague Spring didn’t happen until almost a year later with an ice hockey match some 650 miles away in Stockholm. It was the first major international sporting event between Czechoslovakia and the USSR since the invasion, and the Czechs splurged their hoarded foreign currency allowances to be able to attend and hold up signs such as “Your tanks won’t help you now.” The Czechoslovak players, meanwhile, covered up the red stars on their jerseys. If such provocations weren’t enough, Czechoslovakia won the game 2-0, and a massive celebratory riot broke out in Prague during which the offices of Aeroflot, the Russian state airline, were trashed.

Russia put its foot down. Order was not being maintained in Czechoslovakia, and a new leader more favorable to the Russians had to be imposed. So, in April 1969, out went Aleksander Dubcek, the affable Slovak whose “socialism with a human face” had inaugurated the Prague Spring, and in came a hardline neo-Stalinist, Gustav Husák. (And the Czechoslovak team didn’t even win in the overall hockey tournament: the honor went to the USSR.)

In film, the ramifications were dramatic and, between 1969 and 1970, the film industry was reorganised and the liberal films that were planned and made during the Prague Spring were banned “forever.” As might be expected, these include some of the most caustic commentaries on the nature of communism.

Jaromil Jireš’s The Joke (Zert), for example, charts the bitterness of a student member of the Communist Party who is expelled from university and sentenced to hard labor after a harmless prank directed at a girl he loves. Years later he finds the opportunity to get his revenge on a former friend responsible for his downfall, only to find that life has played a cruel joke on him yet again. The film was so such a stern condemnation of Stalinist methods that it was not only banned but also removed from Jireš’s official filmography.

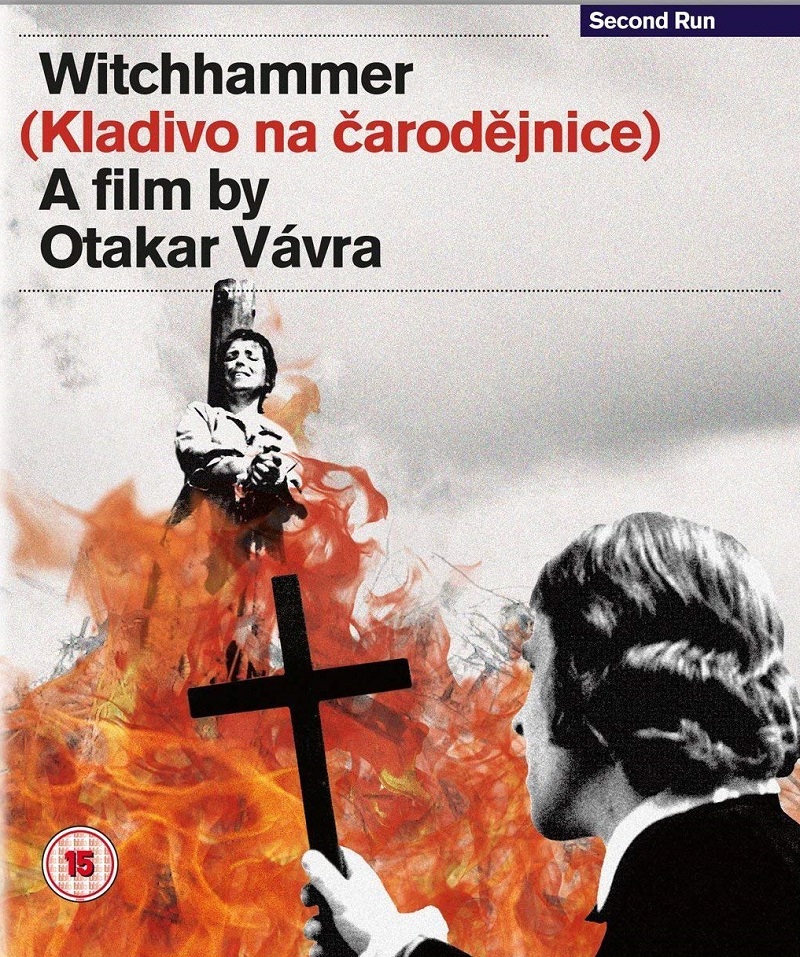

Otakar Vávra’s WitchHammer (Kladivo na carodejnice, 1969) is more allegorical, but it doesn’t take too much to see through his portrayal of the 17th century. Based on historical documents describing witch trials, the film charts how poor superstitious local women are condemned to death as witches by an overly zealous judge. Eventually, the judge’s style raises opposition and the witch-hater accuses his political opponents to protect his position.

The film bears some similarities to the more well-known Carl Theodor Dreyer masterpiece Day of Wrath (Vredens dag, 1943), which did as much to annoy the Nazis as Vávra’s film must have the communists.

After the lively and inventive period of the 1960s, the 1970s and 1980s were largely marked by a desire not to cause offense. While some interesting films were certainly made during this period, there was no hotbed of creativity as seen in the 1960s, and worthwhile films are exceptions rather than the rule.

Making an artistically independent film in 1970s Czechoslovakia was largely a game of smoke and mirrors, of convincing the authorities that the film underway was harmless and didn’t merit supervision. The most effective way of doing this was to work in genre film, and most of the good cinematic works from this period come from styles that the authorities considered generally harmless.

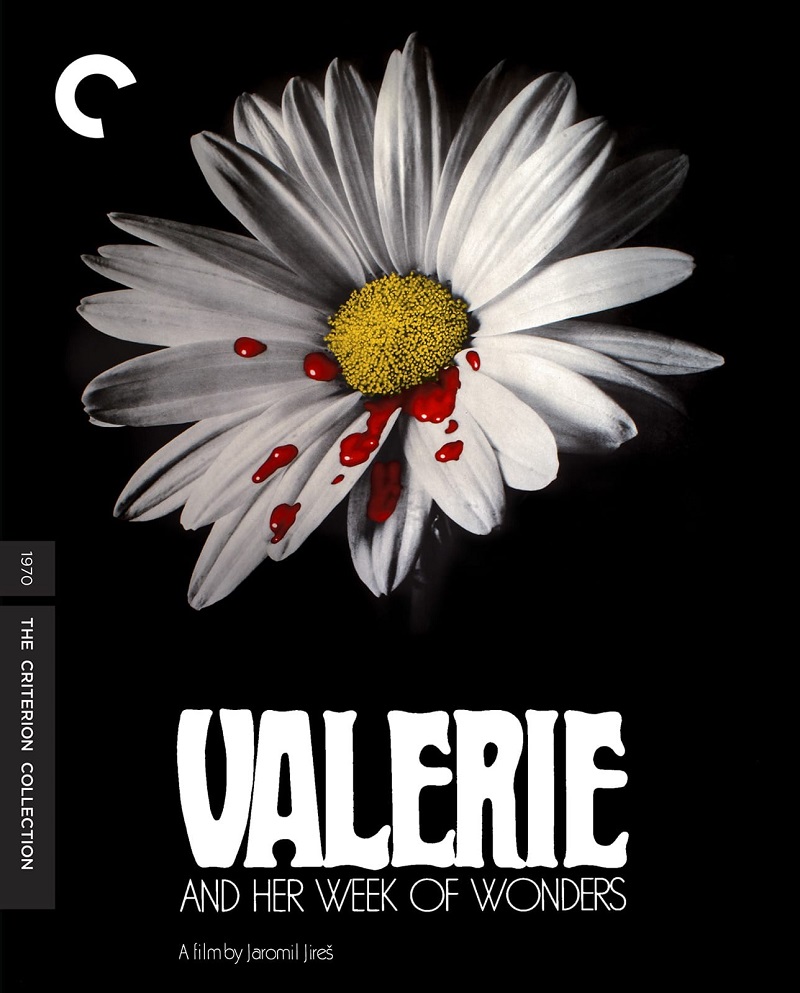

Jaromír Jireš’s Valerie and Her Week of Wonders (Valerie a tyden divu, 1970), for example, presumably must have been presented to the authorities as a fairy tale and a literary adaptation (of a 1930s novel by Vitezslav Nezval). That Nezval had been a committed communist during the inter-war period undoubtedly helped. The result, though, goes far further than a film-of-the-book fairy tale. Part gothic horror film, part children’s story, part soft porn, part political allegory, Valerie and Her Week of Wonders is one of the most famous horror films that Czechoslovakia has produced.

The plot is so labyrinthine that it would be impossible to describe it in any detail (and besides, the story is propelled by poetic mood rather than linear narrative). Suffice to say that it concerns the awakening sexuality of 13-year-old Valerie in a dream world filled with predatory vampires and wicked grandmothers. It may be uncomfortably close to child pornography for some viewers, but the perpetual references to the rape, the images of blood staining white clothes and the theme of the abuse of those who cannot defend themselves by those who should be their protectors could not have been mistaken by Czech audiences at the time.

Valerie and Her Week of Wonders works because of the strength of the fairy tale tradition in Czechoslovakia. In literature, the genre is well-established, while in cinema, its big breakthrough was the 1950s, when actors, writers and poets who before the Second World War (and, therefore, before communism) had been major experimentalists were forced to find ways to express themselves that would not inflame the culturally repressive Stalinist authorities, who viewed such artists with great suspicion and a watchful eye. The result was a series of big budget fairy tales shot in color that shattered the dull years of post-war totalitarianism in the same way that Victor Fleming’s The Wizard of Oz (1939) livened up the gray years of the Depression in the US.

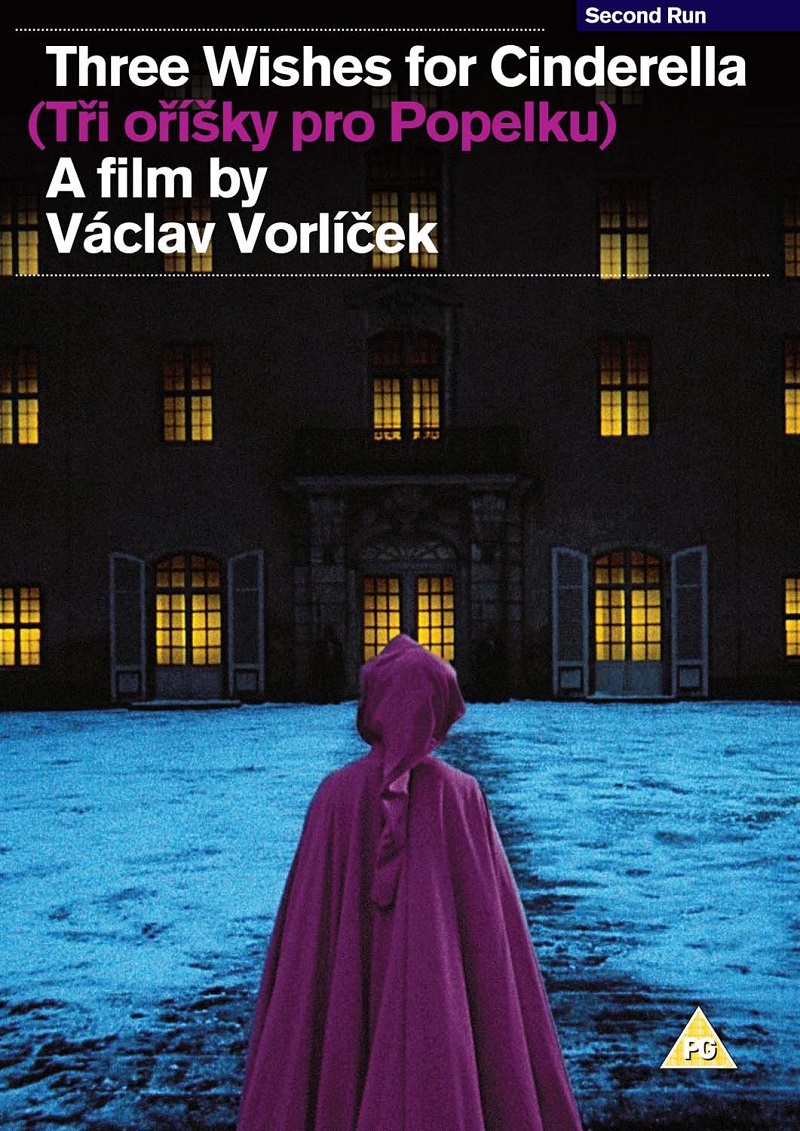

The 1970s was also a pinnacle in fairy tale production, as talented and free-spirited film professionals sought refuge in a genre that was popular, respected and had a fine pedigree for harboring artistic talent fleeing persecution. Probably the favorite Czech fairy tale of all time is Václav Vorlícek’s Three Wishes for Cinderella (Tri oríšky pro Popelku, 1973), and again, its graced with star performances, including a song from the crooning heart-throb of all Czech housewives, Karel Gott. The film is regularly regurgitated on Czech television each Christmas in a prime-time slot and hardly anyone in the country has not seen it at some point.

The tradition lives on today and, although the quality and levels of interest have been more varied than previously, as recently as 2000, the highest number of box office admissions for the Czech Republic for the year went to a domestically produced fairy tale, and a sequel at that, beating out Hollywood hits such as Ridley Scott’s Gladiator (2000).

Jan Švankmajer: The Dark Side of the Fairy Tale

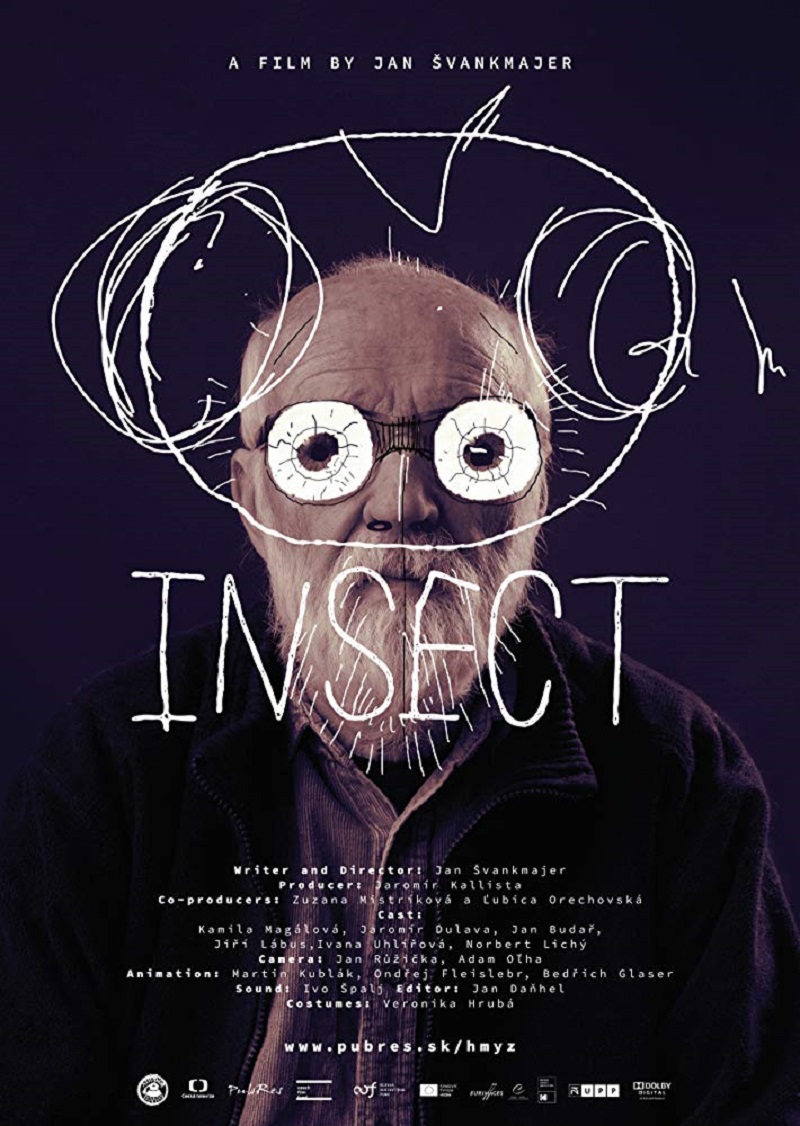

Whereas fairy tales such as Three Wishes for Cinderella bear bright positive messages, Czech cinema has long had an obsession with the Dark Side. The most brilliant and well-known exponent of this trend is Jan Švankmajer, whose grotesque and technically astounding animations have become internationally famous and inspired such homage as a short film by fellow animators the Brothers Quay, “The Cabinet of Jan Švankmajer.”

Inspired by Edgar Allan Poe, Lewis Carroll, Goethe and others, Švankmajer’s films are voyages into interior worlds in which the abstract demons that haunt us are rendered with a disgusting physicality (the oversized animated tongues that flop around always get me). The word “surreal” is often bandied around so much that it almost means nothing now, but Švankmajer is a Surrealist in the proper sense of the term, being a key member of the Czech Surrealist Group and a dedicated prober of what lurks in humanity’s lower layers of consciousness. He’s often been evocatively described as an alchemist, a description that matches both his role as creator and some of the visual props of films such as Faust (Lekce Faust, 1994).

For the first twenty years of his career, from the 1960s to the 80s, Švankmajer made shorts, principally with stop motion animation but also using live action, live puppetry and other techniques. Needless to say, his philosophical approach to film infuriated the authorities, and he spent large portions of this time unable to work. A good selection of these disturbing and original works are available on the DVD series, The Collected Shorts of Jan Švankmajer, Volumes 1 and 2.

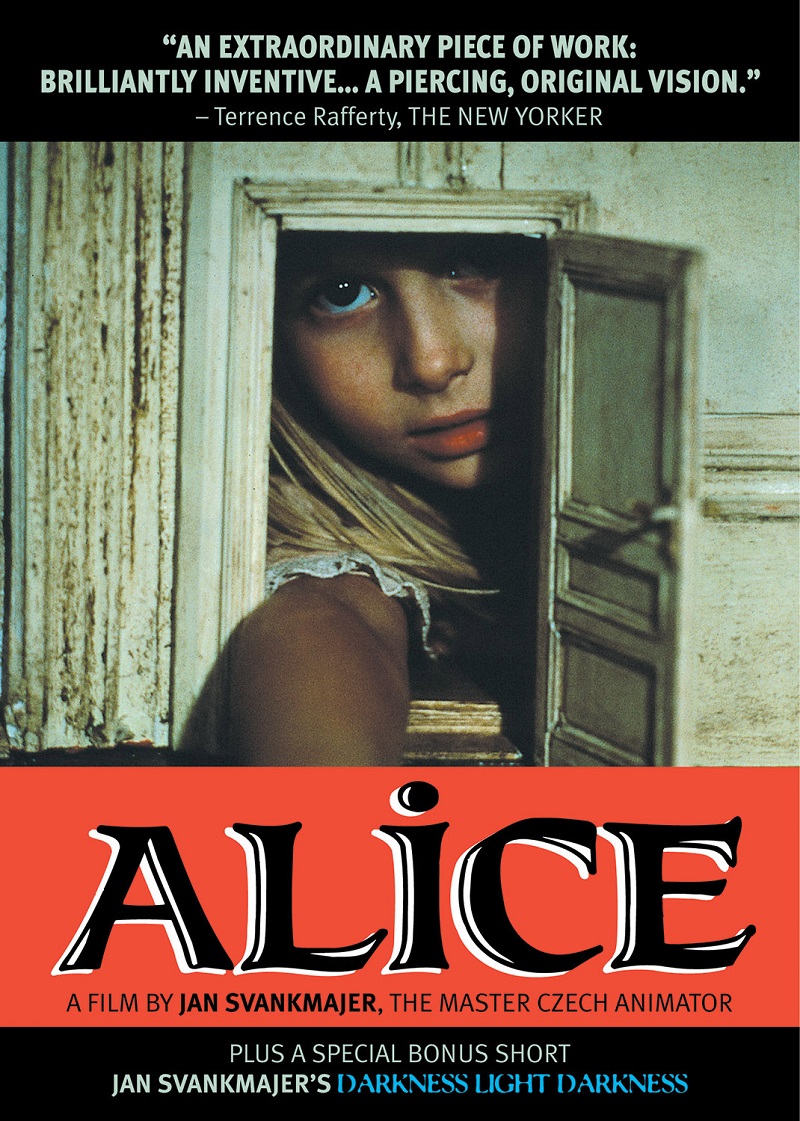

Since the late 1980s, he has increasingly concentrated on feature films that make use of live action with real actors. The first of these features was Alice (Neco z Alenky, 1988), a reworking of Lewis Carroll’s Alice in Wonderland. In the late 1970s, the authorities started forcing the director to work from literary classics, as they thought he couldn’t cause as much trouble with adaptations. But while Alice generally follows the book’s plot, Švankmajer adds a whole new level of meaning to it and the film certainly transcends adaptation in the usual sense of the term. The most morbid and textured of Švankmajer’s features, it is also the most challenging.

Following the fall of communism in 1989, the only restrictions to Švankmajer’s work were financial, and he made three feature-length films in this period. Faust is an adaptation of Goethe’s famous tale of diabolical dealing, reworked to take place in contemporary Prague, with the reading of the original text and the actual events described in the story colliding.

Conspirators of Pleasure (Spiklenci slasti, 1996), practically a silent film, explores the world of secret and bizarre erotic obsessions (but, no, the film isn’t in any way explicit or, paradoxically, even sexy). Czech viewers are rewarded with extra laughs since they’ll recognize real-life news anchor Anna Wetlinská playing herself (with a strange fish fixation).

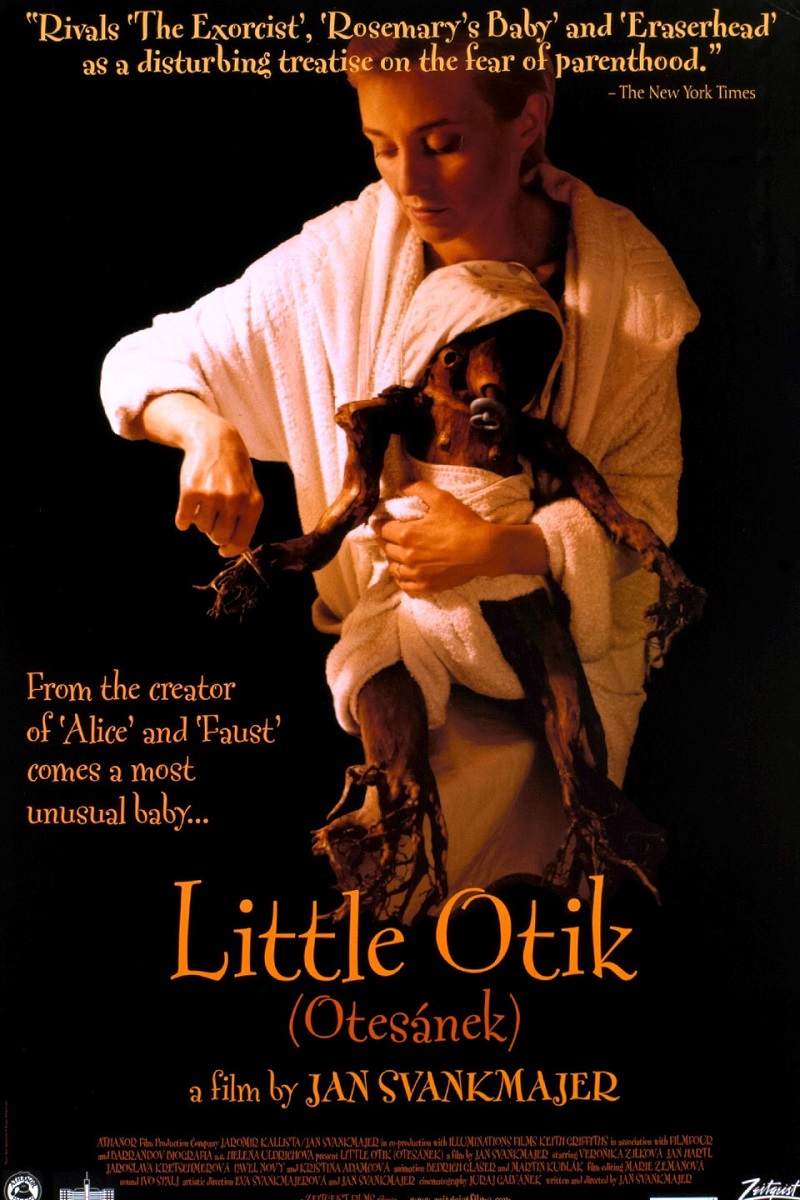

Little Otík (Otesánek, 2000), the most recent of Švankmajer’s films, returns to adaptation of a children’s book, this time a Czech fairy tale about a childless couple that adopt a tree-stump as a boy and find it turns into a crazed man-eating monster. Again, the tale is updated to modern times, and, as in Faust, the original story is read by one of the main characters as parallel events echoing those in the book unfold around.

Also worth noting is that Švankmajer is far from being the only Czech puppet animator of note. Jiri Trnka made a name for himself illustrating children’s books before moving on to animation. Although many of his early works are whimsical in nature, his technical skill shines through: “A Drop too Much,” for example, conveys speed and danger (qualities not naturally associated with puppet-work). Moreover, the sentimental gloss can sometimes be deceptive: “The Emporer’s Nightingale” (“Císaruv slavik,” 1951), for example, clearly advocates rebelling against strict rules. Such an oppositional undertone becomes clear in his last film, “The Hand” (Ruka, 1965), an thinly-veiled allegory of an artist’s plight in a totalitarian state.

Note: we’ve written quite a bit about Trnka, click any of the following to learn more:

- Czech Animation Master Jiří Trnka Documentary

- Watch Jiri Trnka’s Masterpiece – Ruka – The Hand

- Jiří Trnka and the Czech Year (aka Špalíček)

Jirí Barta, like Švankmajer, has also worked with the grotesque. His masterwork is the feature-length The Pied Piper (Krysar, 1985), which mixes a variety of animation techniques and incorporates real, live action rats. His current project is an ambitious adaptation of the legend of the Golem of Prague (already successfully translated into film by Paul Wegener and Julien Duvivier, among others), but it looks like it will never be completed; animation, once state-subsidized, has suffered most of all film forms in the free-market Czech Republic.

1989 Onwards: Nostalgia and Bitterness

The fall of communism in 1989 offered the chance for directors to look at the present and the past with a new honesty – the very formula that had made the 1960s so cinematically successful. Not surprisingly, then, Czech cinema in the 1990s and 2000s has had a large degree of continuity stylistically and thematically with the Czech New Wave. Although critical comparisons between the two eras have generally found the more recent films to be weaker and more derivative, international success has returned to Czech cinema, including an Oscar win and several nominations.

Ironically, as the hardships of adapting to capitalism have hit the country’s economy, Czech film has looked back to the past more with a sentimental warmth than with biting analysis. Jan Svrrák’s Kolya (Kolja, 1995) has been the most successful of these, taking a gently humorous look at Communist oppression and superimposing it over a story of a womaniser who grows up through having to care for a five-year-old boy.

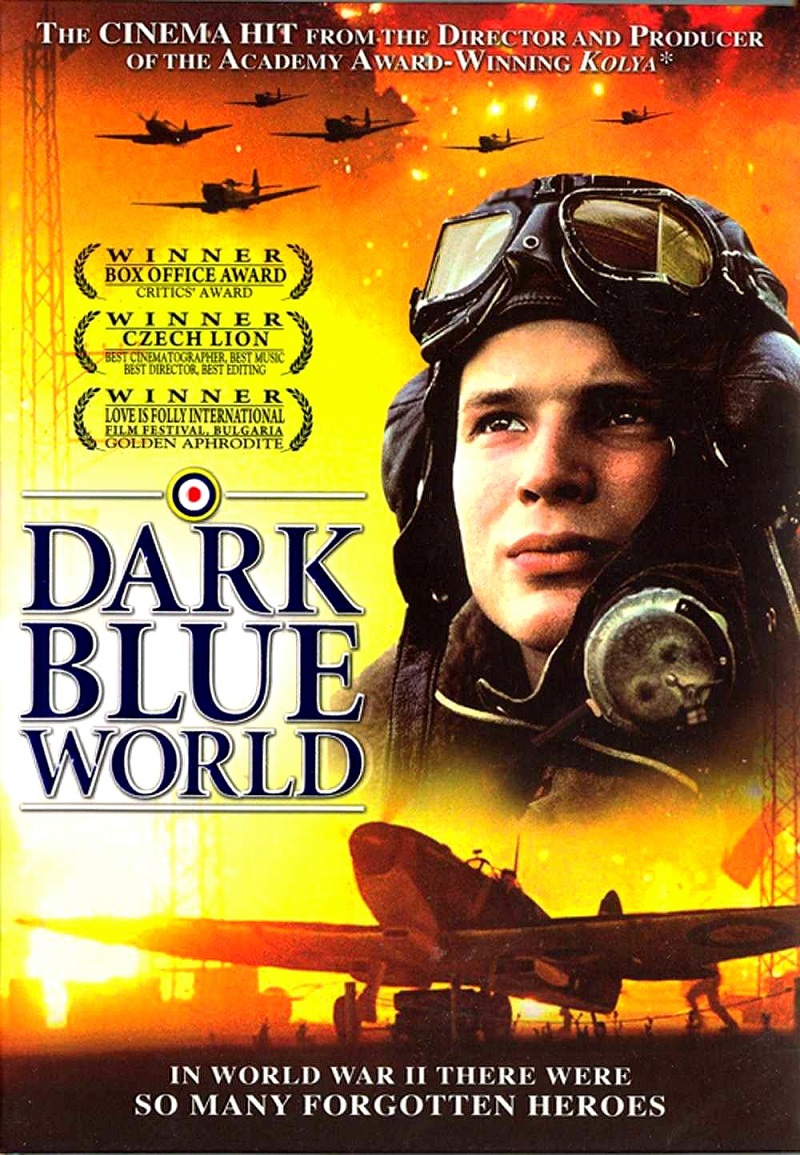

Sverák’s next feature, Dark Blue World (Tmavomodry svet, 2001) rehabilitates Czech pilots who fought on the side of the Western Allies in the Second World War and who subsequently suffered under communism.

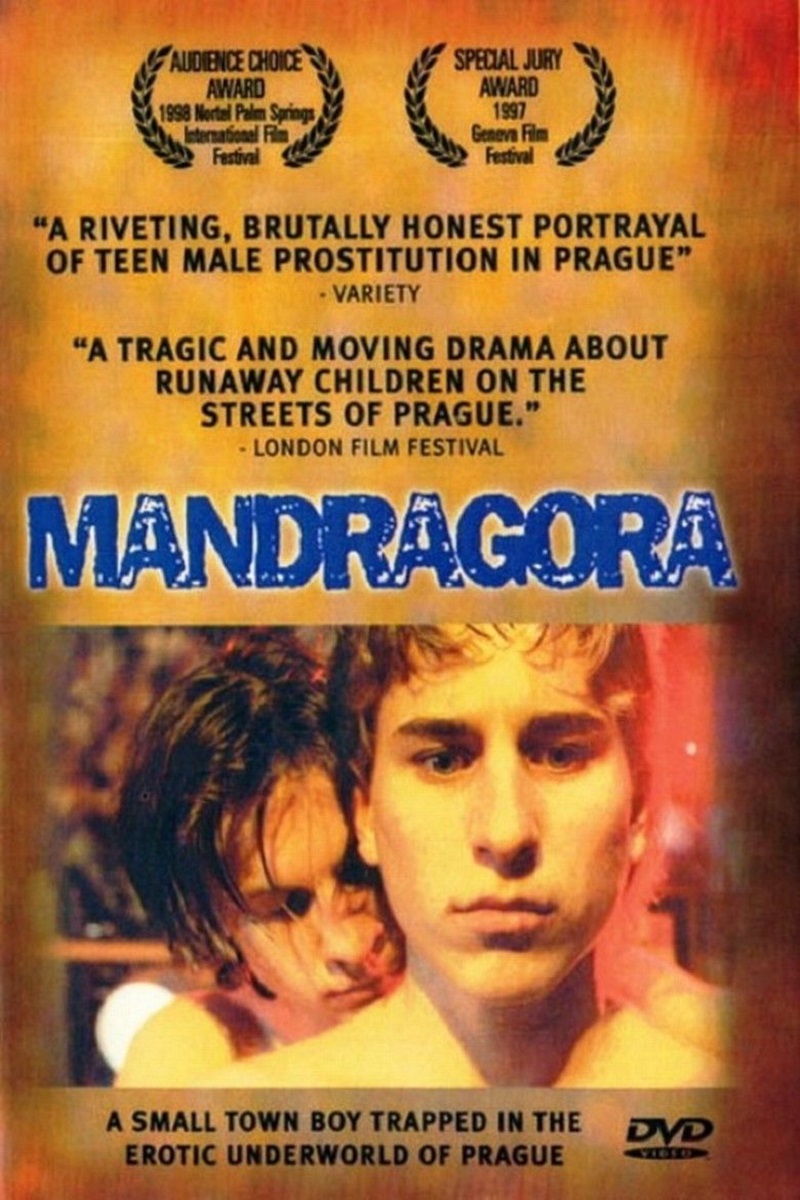

Of the films that have looked at the present, Wiktor Grodecki’s Mandragora (1997) is one of the most scathing, focusing on gay teenaged prostitutes in Prague. The dark, seedy picture it paints of post-communist life was not well-received in the Czech Republic, but you can’t fault Grodecki on accuracy: the film was based on extensive research, as can be seen in his two preceding documentaries on the subject, Not Angels but Angels (1994) and Body without Soul (1996), based largely on interviews with adolescent sex trade workers.

In the early 2000s, there was a small wave of interest in rediscovering the country’s Jewish past, of which Jan Hrebejk’s Divided We Fall (Musíme si poméhat, 2000) is a good example (see the section on Holocaust cinema above.)

Slovakia: The Forgotten Country

While most of the films of the 1960s were made at the Barrandov Film Studios in Prague by Czechs, it shouldn’t be forgotten that the country was then Czechoslovakia and Slovakia had a film culture of its own based around the Koliba studios in Bratislava. Indeed, some Slovaks have preferred to work in Prague, including Jaromil Jireš, Juraj Herz and, since the breaking up of Czechoslovakia in 1992, the “Slovak Fellini” Juraj Jakubisko. Slovak Martin Štrba is now probably the most important and original director of photography in the Czech Republic (as at home, where he still works).

Ironically, the most successful film shot in the Slovak language, Elmar Klos and Ján Kádar’s Oscar-winning The Shop on Main Street (Obchod na korze, 1965) was made by Barrandov. Despite the fact that the dialogue is in Slovak, most of the actors are Slovak and the action takes place in Slovakia, many Czechs still consider the film theirs. The issue isn’t simplified by the fact that the film had two directors, one Czech (Klos) and one Slovak (Kádar) and the screenplay is based on a novel by a Czech author with Jewish roots who grew up in Slovakia (Ladislav Grosman).

Klos and Kádar belong to the older generation, who like Vlácíl and others, prefigured the Czech New Wave. But there was also a Slovak New Wave which produced some equally remarkable films by directors such as Stefan Uher and Peter Solan in the early 1960s, with Jakubisko, Dušan Hanákand Elo Havetta emerging later. Furthermore, Slovak directors working in the 1970s and 1980s frequently made far more hard-hitting films than their Czech counterparts (in Prague, only Chytilová could compete with the Slovaks for independence), largely as Bratislava was further away from the centers of control. Some Czech directors, such as animator Ján Švankmajer, were able to side-step a ban on directing imposed by Prague by filming in the Slovak half of the federation.

Slovakia faired badly in the 1990s, with nationalist autocrat Vladmir Meciar at the country’s helm. Despite promises to boost film production, output fell to a bare trickle. But this didn’t stop the emergence of a major talent, Martin Šulík, whose lyrical films often explore tense father-son relationships. Despite these important works, Slovakia is shamefully under-represented in mainstream views of world cinema history. More DVD releases, Criterion, please!

Andrew James Horton was the Editor-in-Chief of Kinoeye, an invaluable film journal that originated as a column for the Central Europe Review.- – – –

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Thank you in advance!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.