The Czechoslovak Declaration of Independence or the Washington Declaration (Czech: Washingtonská deklarace; Slovak: Washingtonská deklarácia) was drafted in Washington, D.C. and published by Czechoslovakia’s Paris-based Provisional Government on 18 October 1918.

The creation of the document, officially the Declaration of Independence of the Czechoslovak Nation by Its Provisional Government (Czech: Prohlášení nezávislosti československého národa zatímní vládou československou), was prompted by the imminent collapse of the Habsburg Austro-Hungarian Empire, of which the Czech and Slovak lands had been part for almost 400 years, following the First World War.

The article I share today, A New Declaration of Independence, was originally published in New Outlook in 1918. It appeared in Volume 120 and was written by Herbert Francis Sherwood.

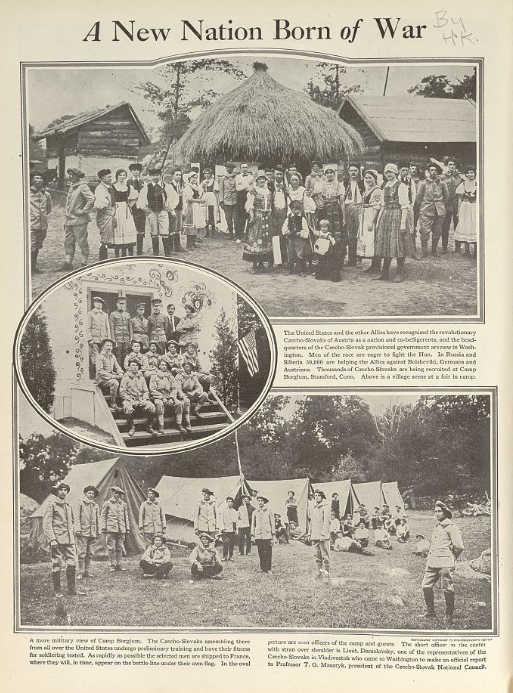

The photographs you see are added from different sources.

It was not a chance through which led to the choice of the historic Independence Hall in the City of Brotherly Love for the promulgation on October 26 of a Declaration of Independence by representatives of eighteen subject peoples of Central Europe. This dream of a federation of freedom loving nationalities of one race, the Slav, grew out of contemplation of what America did in the same place nearly a century and a half ago.

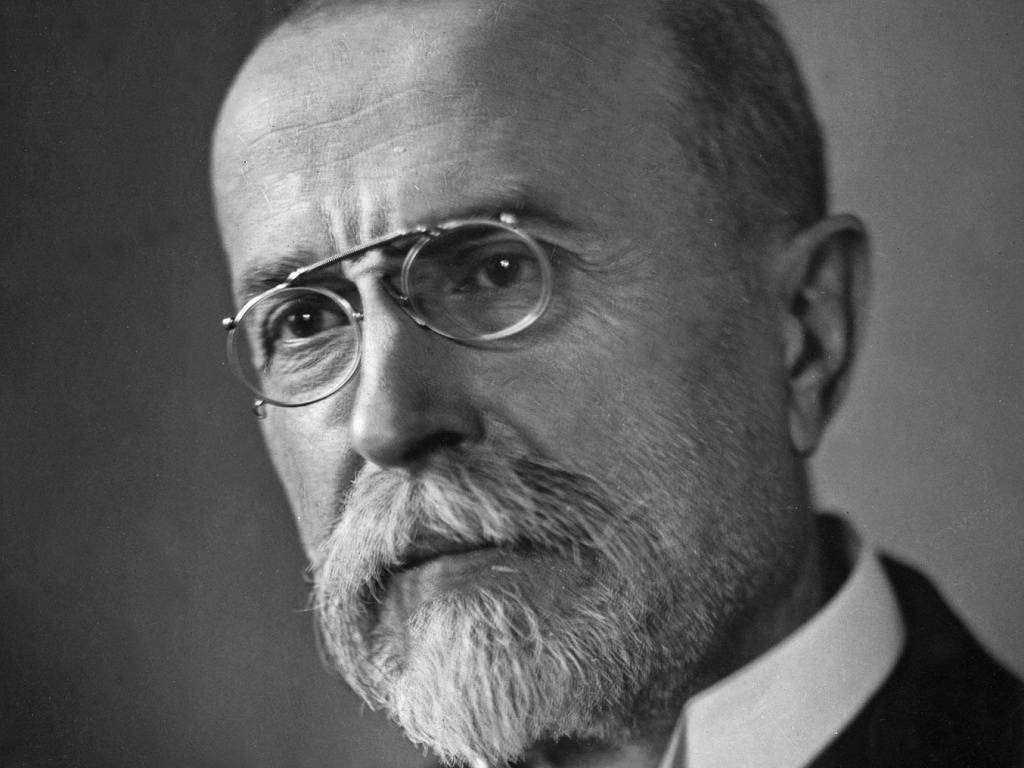

The wife of Dr. Thomas G Masaryk, President of the Czechoslovaks and of the Mid European Union, just formed, is a Brooklyn woman. In the early days of their married life she helped Dr. Masaryk to become acquainted with the famous American Declaration. Since then the Declaration of the thirteen colonies has been one of the guiding influences of his life and ambitions.

Some ten thousand Bohemians and Slovaks recently thronged into Carnegie Hall, New York City, and blocked the streets around the great building in the hope of seeing and hearing him. A report came across the seas that a Czechoslovak army of less than one hundred thousand men had practically freed Siberia from the misrule of the Bolshevists in one of the most dramatic adventures recorded in history. What is the significance of these connected facts?

The various facts mentioned are connected with one man and incentives and means furnished by America. The man is Masaryk.

Who is Masaryk? Very few Americans can answer this question.

It may be briefly stated that for forty years he was a professor in the University of Prague, one of the oldest and best institutions of higher learning in Middle Europe. Through all this period he attracted to his classes Slavs from different parts off Austro- Hungarian Empire; Serbians, Croatians, Slovenes, and Slovaks, in addition to the Czechs of his own country of Bohemia. To them he interpreted ethics, philosophy, democracy, not only in theory, but in practice.

A native of a country which has long sought self-government, a member of a race which is one of the most literate on the face of the earth, a deep and careful thinker, a student of current events, acquainted with American institutions through his wife and previous visits to this country, and last, but not least, a defender of righteous causes no matter how unpopular, at the expense of time, thought, and personal fortune, it is not strange that he has become the leader of his people. They follow him with a devotion born of experience of his wise leadership.

c. 1919. A group portrait of Czechoslovak men, women, and children in traditional dress at a fair at Camp Borglum, a recruitment camp for Czechoslovaks, in Stamford, Connecticut.

Among the things which he saw to be essential to the accomplishment of the desires of his people were a realization of the significance of the position of their country geographically, economically, and from the cultural point of view. Lying between Berlin and Vienna, it had a veto power upon the transportation system joining the capitals Central Empires and Germany with the Orient. Economically and culturally it was one of the chief countries of Mittel-Europa. It was the key to the arch of any scheme for the dismemberment of the Dual Monarchy. Masaryk saw that the destruction of the medieval rule of the Hapsburg dynasty was a first essential to the establishment of a free government in Bohemia.

Bohemia should naturally be the leader in such a movement. Masaryk more than any one else was fitted to bring into being the all important co-operation of the oppressed peoples of Austria-Hungary largely, Slavs like the Czechs. Acquainted with the principles of the American Declaration of Independence, he sought to utilize them as a source of inspiration, and set about the co-ordination of the objectives of the oppressed peoples. Working together, there could be no doubt of the success of the effort toward the dismemberment of the Dual Monarchy. The leaders of the different racial groups realized that it was the old Hapsburg policy of sowing suspicion and cultivating antagonisms between the different races forming the Empire that enabled the dynasty to maintain its grip on the Government.

There was another unifying force, however, greater than that exhibited in the lower house of the Austrian Parliament. From all of the Slav countries of Austria-Hungary, and from Serbia, Montenegro, Rumania, and Poland millions of men had emigrated to America, gathered there new political ideas, and transmitted them back home through letters or carried them back themselves. They had also sent much money home. Here was a common ground of opinion upon which to work and a similarity of ideas upon which to build.

The Congress of the Oppressed Peoples of the Austro-Hungarian Empire held in Rome in April was the formal recognition of the fact that for the first time in the history of the Hapsburg patrimony the various nations gathered under the flags of the Dual Monarchy were co-operating for the destruction of the oppressing power and the firm establishment of free governments based on the desires of the peoples. This spirit of co-operation and the completeness of the programme offered at the Congress were a measure of the life work of Masaryk.

In order to make the accomplishment of their aims more certain the sympathy and assistance of the United States were desired. The millions of Czechoslovaks in this country before the war had formed societies for the cultural development of their peoples. Eleven years ago the Slovak League was organized for the purpose of stimulating the development of the intellectual and moral qualities of the Slovak immigrants. There are now more than two hundred branches.

Since the outbreak of the war the League has actively opposed the Teutonic attack upon Russia and Serbia, the two Slavic countries which then had independence. It urged all Slovaks to co-operate with the Entente Allies in every way possible. When America declared war upon Germany and upon the Dual Monarchy their former home, all American citizens of Slovak birth were encouraged to enlist. Following the decision to form a Czechoslovak army in France, the League undertook the task of securing enlistments among those not eligible for the American Army.

c. 1919. In the oval picture, are seen officers of the camp and guests. The shirt officer in the center with the strap over shoulder is Lieut. Danielovsky, one of the representatives of the Czecho-Slovaks in Vladivostok who came to Washington to make an official report to Professor T.G. Masaryk, president of the Czecho-Slovak National Council.

The Czech societies have also done their part. They are at the back of the Bohemian National Council. Through the machinery which these provide, the Bohemians of this country by stated weekly contributions have financed the work of the Czechoslovak National Council which has been recognized as the Provisional Government of free “Czechoslovakia”. They furnished funds for the use of Masaryk in Bohemia and in the organization of the Czechoslovak troops in Russia. They have equipped and transported thousands of Czechoslovaks above the draft age from this country to France for service there under the command of Marshal Foch.

A part of the last-mentioned work was the establishment of a temporary camp for the future soldiers of the Czechoslovak army on the farm of Gutzon Borglum, at Stamford, Connecticut. Representatives of the Bohemian National, Council before the United States entered the conflict, made clear to the American people the various forms of German propaganda carried on in this country.

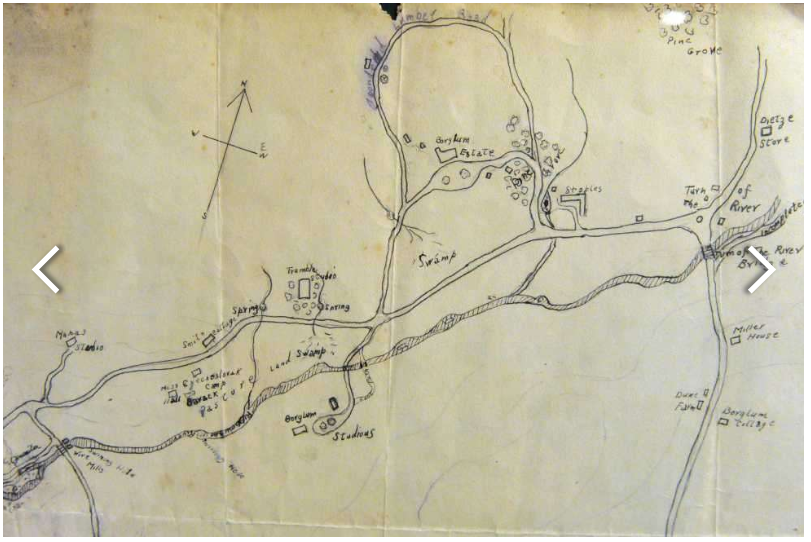

A map of the property and formerly home of Gutzon Borglum, the sculptor who carved Mount Rushmore in North Dakota. It is the land of the Borglum Camp, Stamford, Conn. Borglum used this locale as a studio when he moved to the North Stamford estate in 1914.

So we see as potent factors in the great world struggle between the principles of autocratic and democratic government, among those ranged on the side of self government, a man of ideals with notions of independence, a highly intelligent race willing to die for the right to govern itself, a cohesive body of immigrants from the oppressed peoples of Austria-Hungary to America, contributing ideas and money for the furtherance of the cause of democracy in Central Europe. In proportion to numbers, the contribution has been an immense one It has demonstrated the tremendous potency of ideals, convictions, and intelligence in the face of brute forces.

The reading of the new Declaration while the newly fashioned Liberty Bell, pealed above him was the crowning act of Dr. Masaryk’s life. To him more than to any other man is due the breaking up of the Empire of the Hapsburgs.

[The Philadelphia Declaration announces the following general principles among others 1) That all governments derive their just power from the consent of the governed. 2) That it is the inalienable right of their peoples to organize their own government on such principles and in such form as they believe will best promote their welfare safety and happiness. 3) That there should be no secret diplomacy and that all proposed treaties and agreements between nations should be made public prior to their adoption and ratification. 4) That there will be formed a League of Nations of the world in a common and binding agreement for practical co operation to secure justice and therefore peace among nations.]

These general principles had already been specifically applied in the formal Declaration issued by the National Czechoslovak Council on October 18, at Paris, and also at Washington. This Council sits at Paris. On September 3 the American and British Governments recognized it as the de facto Czechoslovak Government, a recognition since confirmed by France and Italy.

Czechoslovak Government is constituted as follows: Dr. Masaryk, President; Dr. Edward Benes, Foreign Minister; and General Milan Stefanik, Minister of National Defense. These officials signed the Declaration. After stating that Czechoslovakia had been an independent state as far back as the seventh century, and that in 1526, as an independent state consisting of Bohemia, Moravia, and Silesia, it joined with Austria and Hungary in a defensive union against the Turkish danger, and that in this confederation it had never voluntarily surrendered its rights as an independent state, it proceeds to demand the right of Bohemia to be reunited with her Slovak brethren of Slovakia. “Once part of our national state, later torn from our national body and fifty years ago incorporated in the Hungarian State of the Magyars”. The Declaration adds: “Our nation elected the Hapsburgs to the throne of Bohemia of its own free will, and by the same right deposes them.”

Furthermore:

We, the nation of Comenius, cannot but accept the principles expressed in the American Declaration of Independence. For these principles our nation shed its blood in the memorable Hussite wars five hundred years ago; for these our nation is shedding its blood to-day beside her allies in Russia, Italy, and France.

c. 1919. A more military view of Camp Borglum. The Czecho-Slovaks assembling there from all over the United States undergo preliminary training and have their fitness for soldiering tested. As rapidly as possible the selected men are shipped to France, where they will, in time, appear on the battle-line under their own flag.

Finally this Declaration proclaims among other things, the following:

The Czechoslovak nation shall be a Republic. . . It shall guarantee complete freedom of conscience, religion, science, literature and art, speech, the press, and the right of assembly and petition. The Church shall separate from the State. Our democracy shall rest on universal suffrage. Women shall be placed on an equal footing with men, politically, socially, and culturally. The rights of the minority shall be safeguarded by proportional representation. National minorities shall enjoy equal rights. The government shall be parliamentary in form and shall recognize the principles of initiative and referendum.

The Declaration of October 18 is not a constitution, but it foreshadows what the final Constitution of Czechoslovakia will be.

One reason why it has been put out at this time is to meet the argument from the friends of the Dual Empire as it has existed for federalization. The Czechoslovaks do not believe that any proposal for autonomous federalization can mean anything if the Austro-Hungarian Empire is still to be ruled by a Hapsburg dynasty.

The Czechoslovaks declare that “no people should be forced to live under a sovereignty they do not recognize”. In especial, they confirm their conviction that their nation cannot freely develop under a Hapsburg mock federation which would be only a new form of the denationalizing oppression under which they have suffered for the last three hundred years.

Freedom is the first requisite for federalization the Czechoslovaks assert. When this is attained, nations may easily federate should they find it necessary.

In our opinion the two Czechoslovak Declarations of October 18 and October 26 constitute an inspiring appeal to all friends of freedom. – THE EDITORS

Thank you for your support – We appreciate you more than you know!

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Thank you in advance!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

What a history lesson! Thank you.

Great post.