Today we are pleased to share a very informative post about Václav Hlavatý, a world-famous Czechoslovak mathematician and the first President of SVU (Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences, Inc.) written by Martin Nekola, Ph.D.

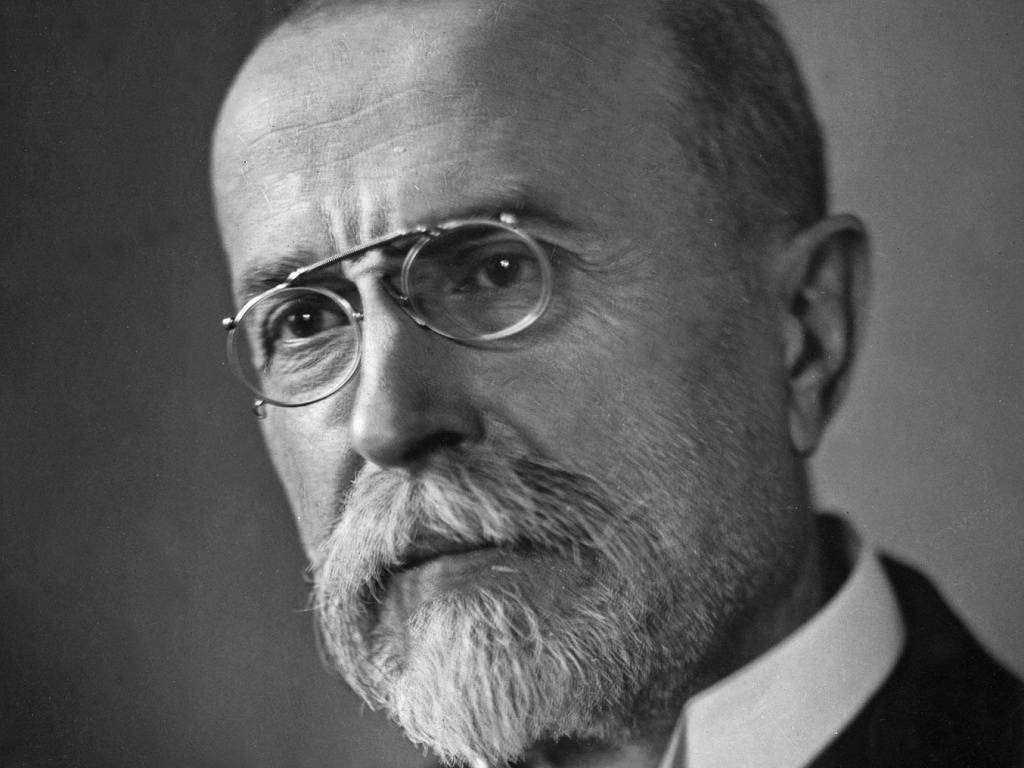

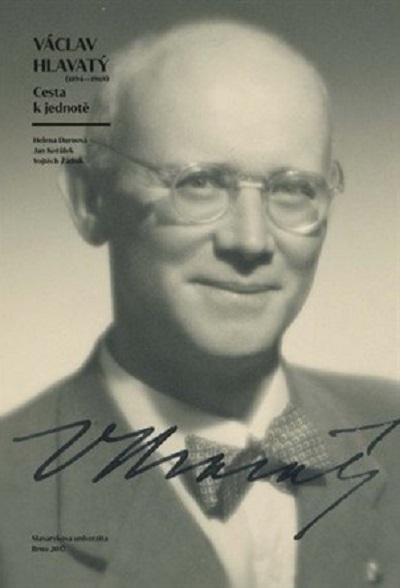

Václav Hlavatý (1894-1969) belonged to the Czechoslovaks most prominent scientists whose work in the mathematics of relativity and the cooperation with Albert Einstein in the 1950s became known worldwide. After the Communist coup in February 1948 Hlavaty moved with his family to the USA and, besides his academic career, sought tirelessly as an important member of the exile community for the return of freedom and democracy to his homeland. Today, Václav Hlavatý’s name is nearly forgotten among the public, despite his undeniable merits.1 Complete archival collection of Professor Hlavaty is deposited in the Lilly Library at the University of Indiana in Bloomington. Numerous material of various character clarify his activities in the scientific, political, cultural and philosophical field as well as his personal life and influence among the Czechoslovak émigrés.2

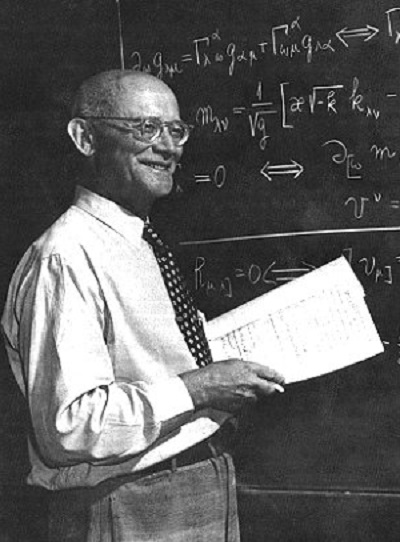

Man of Science

Václav Hlavatý was born on January 27, 1894 in Louny, Northern Bohemia. The father was a C.K. clerk. In the small town next to The Ore Mountains (Krušné hory), Hlavaty studied at municipal real-gymnasium which bears his name today and he became an undergraduate at the departments of Mathematics and Aesthetics of music at the Charles University in Prague in the Fall 1913. His university years were interrupted by World War I. Hlavatý was mandatory enlisted into Austrian-Hungarian army and joined the combat at the Italian front, where he was also captured. He spent most of the war in a P.O.W. camp and returned to Bohemia in the spring of 1919. He successfully graduated one year later and began to teach mathematics and descriptive geometry at several high schools. In addition, he embarked on intensive research in the field of differential geometry. He also carried on his research in the Netherlands, as a member of the team with Jan Schouten, the world-known pioneer of differential geometry and tensors.

In 1925, Václav Hlavatý was appointed Associate Professor of Mathematics at Charles University, a full professor six years later. In that time he already lectured in many countries, published over seventy academic papers, dealing mostly with synthetic geometry and differential line geometry. He contributed to the admirable development of Czechoslovak Mathematics and Physics, but he also managed to get divorced, to marry again and to become a proud father of a single daughter Olga (b. 1932). Václav Hlavatý’s reputation did not escape the attention of Albert Einstein who invited him to Princeton University for a hosting for several months between 1937-38. Then, an important work, the comprehensive textbook „Differential Geometry of Curves and Surfaces and Tensor Number“3 was published. Hlavatý elaborated the differential theory of curves and surfaces in three-dimensional space and helped to open a discussion at the international forum. When Hlavatý returned from North America, the motherland convulsed itself in crisis. The Munich conference on September 30, 1938 and the Nazi occupation soon after fractured the character of the nation and its democratic conviction.

For a short period, Hlavatý still could operate at the university and contribute to reviewed journals. Although strict and uncompromising at the exams, including his notorious derisive remarks on the level of knowledge of examined students, Hlavatý remained very popular thanks to his extraordinary sense of humor, fondness for tennis and of course, music. He masterfully played the violin and performed as a professional musician within a quartet. After the closure of universities on November 17, 1939 by the German occupants, Hlavatý returned from Prague to his native town of Louny and fully devoted himself to his scientific work. During World War II, he essentially focused on differential linear theory and projective geometry. When the Prague uprising against the Nazis broke out in early May of 1945, Hlavatý left the shell of inert concentrated scientist and joined the fighting on the barricades without hesitation.

Postwar Intermezzo

Immediately after the liberation, Hlavatý plunged into the vortex of academic life. He significantly contributed to the establishment of the Institute of Mathematics in Prague.4 Besides Hlavatý, the Institute concentrated also other leading scientist from interwar period, professors Miloš Kössler, Vojtěch Jarník (Analysis), Vladimír Kořínek (Algebra) or Bohumil Bydžovský (Analytical geometry). He taught mostly descriptive geometry. Former students remembered him as strict and fair lecturer and a helpful mentor, always ready to assist young colleagues. He usually smoked during his lessons and did not mind when the students in the pews indulged in the same vices. He even threw them matches from behind the desk and offered his expensive cigars.

Hlavatý left Czechoslovakia for couple of months in October of 1945 to realize a lecture tour at various U.S. universities. Although he was offered a full-time job at established research centers, Hlavatý returned home and peered also into the hitherto unknown field of politics. Only for one month between April and May 1945 he served as a member of the Czechoslovak Interim National Assembly, as a substitute for deceased. Both Hlavatý and the Czechoslovak National Socialist Party who nominated him understood he was not the ideal choice for that position. Plainspoken, Western-minded, intolerant to empty talking who did not hide a strong dissatisfaction with the penetration of the Communist Party in all spheres of public life and with the inability of the democratic camp to face the red pressure. His opinions became too critical and therefore uncomfortable. After the parliamentary elections on May 26, 1946, Hlavatý bid farewell to politics again.

At the beginning of the fateful year 1948, Professor Hlavatý received another invitation to the USA from Albert Einstein. He was very sceptical about political development in Czechoslovakia after the Communist coup on February 25, 1948 and the mysterious death of the popular minister of foreign affairs Jan Masaryk. Hence, he emigrated and continued with his work in the free world. After a part of the spring semester spent at Sorbonne in Paris Hlavatý, together with his wife and daughter finally left Czechoslovakia in late July 1948. The departure date changed several times because of bureaucratic delays and intentional obstacles, but in the end, the Communist power enabled the family to cross the border legally.5

A New Beginning in Indiana

Václav Hlavatý’s immediate professional success partially dampened obvious homesickness. He gained a permanent teaching position at the University of Indiana6 and moved to Bloomington, a small town surrounded by endless fields and meadows of flat agriculture state of Indiana. A modest brick house in a quiet street became Hlavatý’s home for the next two decades, whereas the Swain building in the middle of the campus where the Institute of Advanced Mathematics was based, served as his scientific workplace where he has achieved fantastic success in upcoming years.

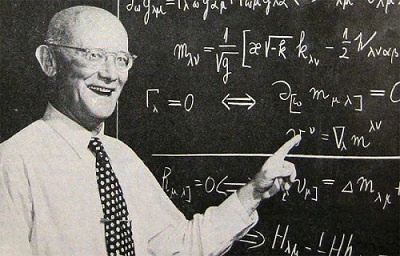

Since 1952, Hlavatý was a full professor in Bloomington, and just a few months later his name attracted attention of the entire scientific world. For some time he worked on mathematical elements of Albert Einstein’s theories and in the Spring of 1953 it was officially announced that he had solved the unbelievably complex and involved equation (with sixty-four unknowns) of Albert Einstein’s “Unified Field Theory.” This set of equations Einstein hoped would embrace a description of everything in the universe. HIavaty told a New York Herald Tribune reporter, July 30, 1953, that his solution provided the mathematical vehicle for understanding everything in the universe as Einstein had hoped. He said his solution described the process by which matter and energy could be described in terms of electromagnetic forces, and he thought it would prove a reconciliation of the apparent disparity between the relativity theory and quantum mechanics. The theory and the solution constituted the basis of the universe itself as it was held together by the electromagnetic fields.7 New York Herald Tribune also ranked Hlavatý among the top ten scientists worldwide.

After many adjustments and editorial interventions, Hlavatý´s discovery lived to see the book release. The work titled „Geometry of Einstein’s Unified Field Theory“ was first published in 1957.8 In terms of mastering the most complicated calculations through geometric interpretation the contribution of Professor Hlavatý brought astonishing mathematical results and was worthily praised for this contribution. However, Einstein himself deserved all his strength to the improvement of theory, which later showed to be a dead end, from a point of view of physics. Hence, its mathematical solution developed by Hlavatý remained essential and important, but mostly on a theoretical level. It also confirmed or eliminated a number of hypotheses about the general physical laws of the universe. Hlavatý was satisfied he could have shown the direction of future research to younger generations of mathematicians. Many of the best were his students and colleagues in Bloomington and they did not forget to appreciate Hlavatý´s life-work by publishing an academic proceeding called „Perspectives in Geometry and Relativity: Essays in Honor of Václav Hlavatý“9 Altogether Forty seven mathematicians, astronomers and physicists from North America, Asia and Europe sent their contribution, none from Czechoslovakia.

As a defector and a traitor of the working class, Václav Hlavatý remained persona non grata for the Communist power. As a deeply respected expert, he was invited to lecture tours around the USA and the globe. The longest one in 1961 took six months. He talked about himself jokingly as a „regular multiplication table guy“ (obyčejný násobilkář) but responsibly presented his research. He also never forgot what was his country of origin and always greeted the audience in the name of Czechoslovak democratic exile. Back in Bloomington he was honored to receive the title Distinguished Service Professor in 1962, he was a member of editorial boards of leading mathematical journals, he climbed on the absolute top of his scientific discipline.10

Václav Hlavatý always told his students to oppose destructive communist ideology, but he also manifested himself as a defender of democracy, civil rights and human decency. In early 1950s, there was a job opening for a secretary at the Institute of the Advanced Mathematics at the University of Indiana. A committee of Math faculty members including Hlavatý was formed to interview the candidates and select one to fill the position. They met three candidates and unanimously selected one very bright and qualified young lady to work at the university. The head of the committee informed the head secretary of the department office. She said: „I will not work the gal you selected because she is a negro.“ The head of the committee proposed to pick somebody else to avoid the conflict among the secretarial staff, but Hlavatý refused to go along. The matter got on the table of the president of the university, Hermann B. Wells. Hlavatý warned him in advance he would resign as a professor if the black lady was not hired. Subsequently, the best candidate was hired indeed. However, due to the misbehaviour of her colleagues, she quit the job shortly after.11

Exile Life

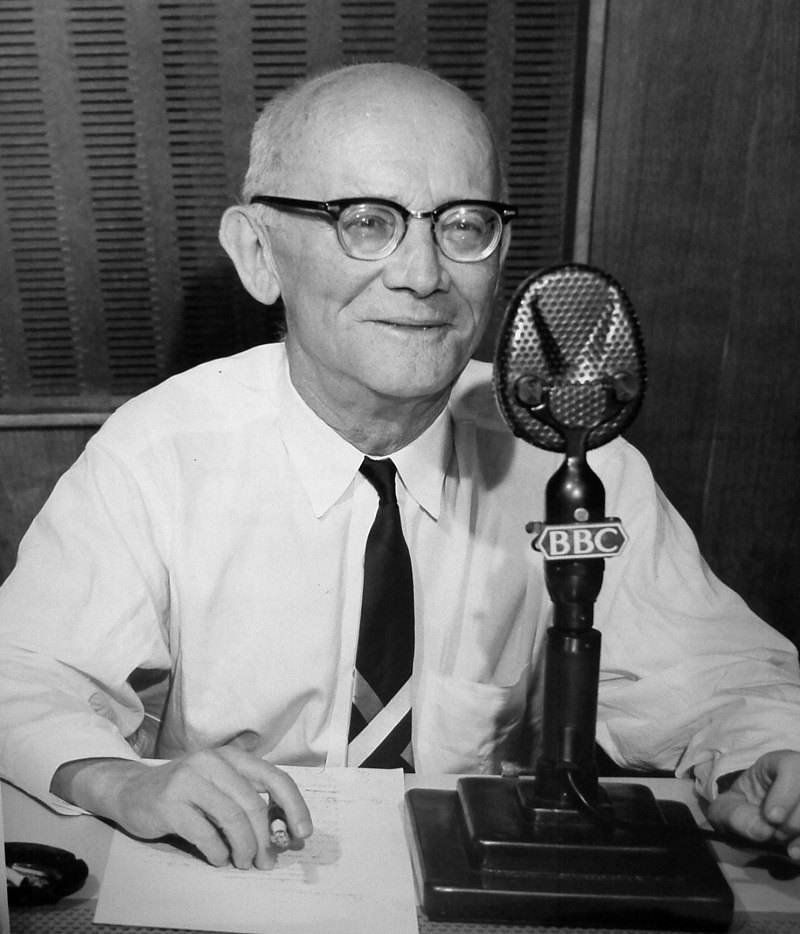

Václav Hlavatý belonged to Renaissance personalities with a wide range of interests. He wrote numerous reflections about social issues, politics, philosophy of science, religion, moral principles, art or history, he also devoted himself to spiritual issues and the existence of mankind in the infinite universe. He often quoted the works of St. Augustine, Immanuel Kant, Henri Bergson, and Albert Einstein, naturally. In 1950, a proposal for the federalization of Central Europe and the discourse about the importance of Czechs and Slovaks in the future development of the continent came out from Hlavatý’s pen. He also often talked on the waves of Radio Free Europe and Voice of America.1

After complicated negotiations, the Council of Free Czechoslovakia (Rada svobodného Československa) was established on 25th February 1949, with the ambition to become an unifying umbrella body of the entire democratic exile. Former politicians, partymen and diplomats, who took leadership positions within the Council showed themselves as unable to reach broader consensus and to stifle mutual disputes. Therefore, the Council, after a promising start, was increasingly paralyzed and disintegrated. Václav Hlavatý was one of the few independent, non-partisan members who tried to bring quarrelling fractions to the meeting table and also to set reasonable conditions for future coexistence. At the meeting of the Council on June 18, 1954 Hlavatý said: “The nation who gave Masaryk to the world has to show that his ideals can me implemented in the real politics. In current situation when the cultural mission of the nation is choked by a hostile ideology is a duty of the exile to serve as the pillar of the nation´s soul.”13

Hlavatý´s effort to establish a better spirit of cooperation resulted in two analytical studies with concrete proposals for reorganization, changes in statutes and daily functioning of the Council of Free Czechoslovakia, “Again and better” (Znovu a lépe!) and “For revival of the exile” (O obrodu exilu).14 Despite Hlavatý´s well-meant efforts and support from many respected exile personalities (former minister Ladislav Karel Feierabend, diplomats Ján Papánek, František Schwarzenberg, Edmund Řehák, sociologist Otakar Machotka and others) his proposals were rejected, and the Council continued to be lost in the never-ending crisis. A deep disappointment from “politicking” reinforced Hlavatý´s belief the foundation of another, strictly non-political exile center was urgent. Thus, the idea of the Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences in America (Společnost pro vědy a umění – SVU)15, a non-profit, scientific, cultural, educational, literary, and artistic organization was born in the second half of 1950s.

Safe Haven of Intelligentsia

The idea of formation the SVU came from the conference of the Czechoslovak National Council of America (Československá národní rada americká)16, the major and the most influential compatriot organization in North America with more than 250 000 members and 16 regional branches, in May 1957. The idea was to concentrate the scientists and the artists in exile, to maintain the rich tradition of free Czechoslovak science abroad before it could be restored back home, to follow the latest development in various academic and cultural disciplines and to contribute to international scientific life.17

Similar ideas appeared already in early 1950s but the established bodies then (Sdružení československých vědeckých pracovníků v exilu, Kulturní rada) did not reach the necessary acquaintance and authority. Although scattered throughout the world, the Czechoslovak scientists wanted to be in touch, to meet regularly and to exchange experience, to inform others about their own successes. Newly formed SVU should have met all requirements. Hlavatý himself emphasized the activity of Czechoslovak scientists, artists, authors, teachers or lecturers as one of the main tasks of the exile: „In the first and second exile (Masaryk’s action during WW I and Beneš’s action in WW II) we could show that we had skilled soldiers and two excellent politicians. This current exile consists of many outstanding researchers, and it would be a sin not to show them to the world. (…) The „science“ realized at home by the Communists is more or less

disregarded and, in a certain sense, we serve here in the exile as a model and show-case of the entire nation.“18

From February 1958 a preparatory committee was operating and on its first regular meeting on October 24, 1958 in Washington D.C. Hlavatý was elected the very first Chairman of nascent organization.19 Professor of law Vratislav Bušek (1897-1978) and composer and conductor Rafael Kubelík (1914-1996) assisted him as Vice-chairmen. For a daily agenda and organizational matters, the position of Secretary General was crucial. In the first years of SVU, lawyer Jaroslav Němec (1910-1992) and Professor of philology and modern languages Rudolf Šturm (1917-2005). One of the first tasks of SVU was to create a newsletter as the main communication channel for the membership.

Monthly News of SVU (Zprávy SVU) commenced publishing in September 1959 under the editorship of journalist Ivan Herben (1900-1968). From the beginning, the journal had the form of austere information brochure and faced a lack of finance, since the members received it for free. Hlavatý and Bušek insisted on the establishment of an independent join-stock company, which would publish, distribute and sell Czech and Slovak books and texts, written by SVU members.20 Arts and Sciences Publishing Corporation came into being indeed, but after a short time had to be disbanded. In January 1964, a new important periodical, quarterly Metamorphoses (Proměny) edited by novelist and essayist Ladislav Radimský (1898-1970), started to be published. Václav Hlavatý persistently lobbied for realization of the project with Radimský in charge. With contributions from dozens of established SVU scholars and authors and with more than one hundred issues released Metamorphoses lasted until 1991.21

SVU gradually established, besides the headquarters in New York City, seven regional chapters in North America and Europe (Chicago, Boston, Pittsburgh, Washington D.C., Montreal, Toronto, Munich). From just 198 in June 1958, the number of members increased to more than 1300 in a decade, after the arrival of a new wave of Czechoslovak émigrés in 1968.

SVU regularly met on its General Assembly meetings which should have addressed organizational matters and operational challenges, and congresses convened once every two years where the members had the opportunity to share and to present their scientific work with the others. Amount of the contributions at each congress usually exceeded one hundred.22 The first meeting of SVU General Assembly took place in New York in April 1960, while the first congress was held two years later in Washington D.C.

Václav Hlavatý’s extreme workload and often lecture tours, above all his six-month-long trip in 1961, when he visited Europe, Japan, India and many other countries (he called the trip good-humoredly „round the world with the multiplication and the spouse“) naturally did not allow him, to manage SVU on a daily basis. He willingly delegated most of the paperwork to his colleagues and insisted that SVU needs to be a living body based on flexible young people, to avoid the unenviable fate of other exile organizations, blunted by few old conservatives. He saw the support to succeeding generations as crucial. In the closing speech at the fruitful first SVU congress in 1962 he stated: „This congress was organized by young generation, having the main responsibility for its success. And that is something heartwarming. It is clear our national group will prevail if we are able to meet the intellectual needs of the youth…“ 23

It should be mentioned Hlavatý’s enthusiasm dropped after some time. On January 1, 1961 he sent a warning letter to the rest of SVU officials: „There is no essential temperament difference between the exile and the nation at home. We have the same merits and suffer the same mistakes, meaning the growth of moral apathy. It may be excusable behind the Iron Curtain due the psychological terror of the government, but is absolutely unacceptable by the émigrés in safe. (…) I thought I would be able to establish SVU as fearless institution, a guard of moral values which would defend its standpoint in every crisis. We are not a liberation guild, , our goal and wish is to help by searching for moral values which our nation is consistently loosing since 1938 and devaluing under the guise of realism. In this I see the importance of SVU. If we loose some members, that would be only those who did not understand the nature of current moral crisis of our small nation. The quantity is not always the pointer of the right path. We have lived through many moral crises in the exile. Some still remain. (…) If the intellectuals fail in moral intransigence, they betray the nation in its moral nature. Do not let it happen!“24

The resignation as Chairman in 1962 and transfer of leadership to René Wellek (1903- 1995), Professor of literary theory and criticism at Yale, gives evidence that his appeals were not answered. The decision certainly resulted in the lack of time to fully administrate SVU, but the main reason is to be seen in Václav Hlavatý’s different views on certain topics. Similar explanation offers his letter to Ladislav Radimský from June 1963: „When SVU was founded, my intention was to achieve two things and customize everything to them: 1) strong moral support in behalf of the homeland 2) the recognition of intellectual abilities of our exile at the international forum. Unfortunately, the others did not share my attitude. It was a disappointment for me. (…) I left SVU Executive Committee a year ago. They did not want to accept it. I asked many times already to remove my name from the letterheads, without any result so far…“25

Václav Hlavatý wrote his objections to his successor, Prof. Wellek too: „SVU congress showed to our host country that just do not beg but we are also able to give. It fulfilled its role of professional scientific symposium and a valuable social link too. But no such a reunion can replace intellectual connection of those who need the intellectual sustenance regularly, not just once a year…“26 At this point, Hlavatý´s effort resulted at least in collecting sufficient cash and the launch of publishing of Metamorphoses, offering the „intellectual sustenance“ in the form of reflections, essays and analyses he was calling for.

Václav Hlavatý became Chairman of SVU once again, in the years 1966-1968. It is not apparent why he accepted the position. In contrast with his first term Hlavatý showed only limited activities, he struggled with health problems and also left USA for several months. He constantly refused to write speeches or opening texts for SVU’s prints he had been asked for, showed general fatigue, disgust, indecision, loss of objective perspective and humor he used to be known for. His friends and colleagues from SVU noticed the change of Hlavatý’s personality and after few futile attempts stopped trying to engage him.27

Genius’ Unsolved Equations

The last years brought a full recognition of Hlavatý´s lifelong scientific work.28 He was named Professor Emeritus of Mathematics by the University of Indiana. In 1968, a scholarship carrying Hlavatý´s name was established by the university to be awarded yearly to outstanding young mathematicians. Top scientists around the world read his papers with a deep respect. He was the member of editorial boards of recognized journals like Tensor in Japan, Rendiconti di Circolo Matematico di Palermo in Italy, Journal of Rational Mechanics and Analysis in the USA and others. The number of his articles increased to one hundred and seventy.

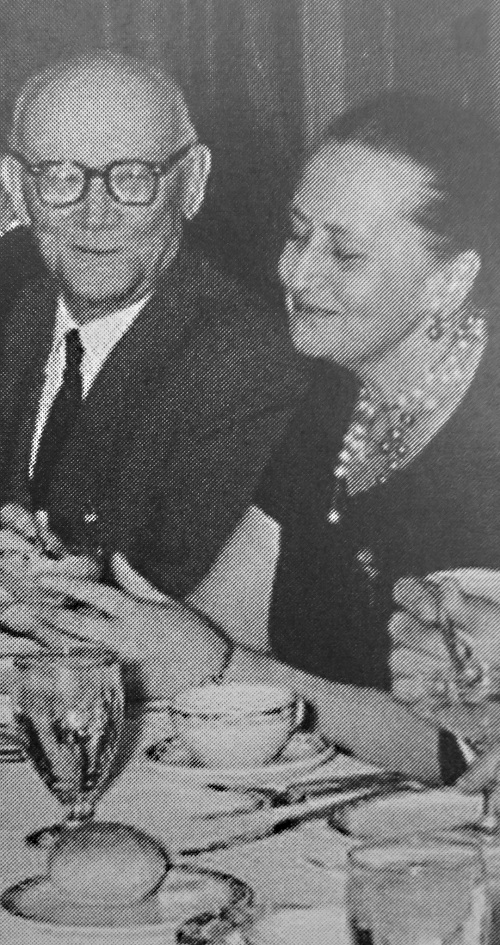

On the contrary, he suffered tragedy in personal life. His beloved wife underwent severe heart attack and remained partially immobile. Hlavatý cared for his wife at home but due to a permanent nervous tension and inadequate eating began to lose weight, often fainted, suffered depressions. Mrs. Hlavatý had to move to a nursing home where her condition improved enough to travel to visit their daughter Olga and four grandchildren to Afghanistan. Olga married an Afghan student in 1950 and moved with him to Kabul. Mrs. Hlavatý stayed with the family for a couple of months and died in her sleep in September 1966.

Professor Hlavatý orphaned in his house in East Grimes Lane in Bloomington. He was losing his eyesight and had to have two treatments to fix it. Together with a serious abdominal operation and worsening mental problems, Hlavatý’s life was threatened. Despite the insistence of doctors, he did not rest and worked to exhaustion. He also accepted the invitation of Pakistani government to help establish a national science institute in Islamabad. After some time spent there, he returned to Indiana but intended to complete the unfinished business in Pakistan and then to move to Chile.

Aware of his own mortality and the transience of all secular, Václav Hlavatý often turned to God and read religious poetry. He wrote to his relatives, old friends, schoolmates and students in Czechoslovakia. He had a great desire to visit hometown Louny or to take a spa treatment in Marienbad. All application for necessary permits at Czechoslovak consulate went directly to State security departments in Prague, always with the dismissive response.

Václav Hlavatý’s physical and mental strength waned. After the return from the first contract in Pakistan in Spring 1968, he was fully occupied with the calculations to simplify algebraic classification of relativistic space. In his own words, he would need leastwise two years to finish that work. Two years he did not get. Professor Václav Hlavaý died on January 11, 1969, two weeks before his seventy-fifth Birthday, in his house in Bloomington.

He left behind unfinished work and also generations of first-class mathematicians who pushed the frontiers of human knowledge bit further. Author of Hlavatý’s obituary in prestigious British journal Nature called him the largest successor of Albert Einstein and one of the most important scientists in the twentieth century. After the fall of the Iron Curtain also Czechoslovakia finally valued Václav Hlavatý by the Order of Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1991) and the Honorary Citizenship of beloved town Louny (1992).

FOOTNOTES -

1) Life and work of Vaclav Hlavaty remind, except of numerous short memorial sketches, just few articles published in reviewed journals. See František NOŽIČKA: Profesor Václav Hlavatý, český matematik světového jména. In: Časopis pro pěstování matematiky, Vol. 94 (1969), No. 3, pp. 374-380 cf. Oldřich KOWALSKI: Věnováno Václavu Hlavatému (Některé dokumenty o životě a díle). In: Pokroky matematiky, fyziky a astronomie, Vol. 38 (1993),No. 2, pp. 65-81.

2) In the summer 2014, author of this text had the opportunity, thanks to a generous financial support from RSJ a.s., to do a deep research of Václav Hlavatý collection in Bloomington, as one of the first researchers from the Czech Republic, and has already published several articles on Hlavatý in Czech popular and reviewed academic periodicals, including a detailed report on the collection content. See Martin NEKOLA: Zpráva opozůstalosti matematika Václava Hlavatého v amerických archivech. In: Archivní časopis (4/2014), Ministerstvo vnitra ČR,Praha 2014, pp. 369-376.

3) Václav HLAVATÝ: Diferenciální geometrie křivek a ploch a tensorový počet, Jednota československých matematiků a fysiků, Praha 1937.

4) Full name of the institution founded on March 14, 1947 is the Institute for Mathematics at the Czech Academy of Sciences (Ústav pro matematiku při České akademii věd)

5) Archives of Czechs and Slovaks, University of Chicago, BOX Hlavatý (No. 755), Letter of Václav Hlavatý to Petr Zenkl, 11. February 1949.

6) It is little known that also other professors of Czech origin were affiliated with the university for many years. Political science was lectured by Václav Beneš (nephew of president Edvard Beneš), Chemistry by Miloš Novotný, Neurology by Oldřich Kolář neurology, Biochemistry by Felix Haurovitz, Psychiatry by Jiří Hanuš Grosz, and Literature and Slavic languages by well-known poet and translator Bronislava Volková.

7) William L. LAURENCE: Czech Refugee Finds Electromagnetism Is Basis of Universe. In: Walter SULLIVAN(ed.): Science in the Twentieth Century, New York 1978, pp. 73.

8) Václav HLAVATÝ: Geometry of Einstein's Unified Field Theory, Noordhoff Ltd., Groningen 1957.

9) Banesh HOFFMANN (ed.): Perspectives in Geometry and Relativity: Essays in Honor of Václav Hlavatý,Indiana University Press, Bloomington/London 1966.

10)František HOUDEK: Einsteinův obyčejný násobilkář, In: Karel PACNER, František, HOUDEK, Libuše KOUBSKÁ (eds.): Čeští vědci v exilu, Karolinum, Praha 2007, pp. 64-66.

11) Letter from Professor Jagdish Lal Nanda (Hlavatý´s former student) to the author, November 2014.

12) Some of Hlavatý´s interviews and speeches are deposited in the Archives of Czechs and Slovaks at the University of Chicago. Author of the article is in possession of the copies of these audio records.

13) Lilly Library, University of Indiana, Hlavaty MSS II., BOX 1, Speech of Václav Hlavatý, 11. June 1954.

14) Václav HLAVATÝ: Znovu a lépe! : (studie o politické situaci čs. exilu), Svobodná Československá Tisková Společnost, Čechoslovák-FCI, Londýn 1955; O obrodu exilu: dokumenty o akci prof. V. Hlavatého, Československý zahraniční ústav v exilu, Chicago 1956.

15) The archive of SVU consisting of 75 linear feet of manuscript and print materials is deposited at the Immigration History Research Center (IHRC), University of Minnesota.

16) See Joe MARTÍNEK: The Czechoslovak National Council of America, ČSNRA, Chicago 1962.

17) Lilly Library, University of Indiana, Hlavaty MSS II., BOX 2, Odůvodnění návrhu na založení Společnosti pro vědy a umění (undated).

18) Lilly Library, University of Indiana, Hlavaty MSS II., BOX 1,Letter of Hlavatý to Otakar Machotka, 7. September 1952.

19) All important events in formative years of SVU are described chronologically in Miloslav RECHCÍGL: Pro vlast: padesát let Společnosti pro vědy a umění, Academia, Praha 2012, pp. 21-44.

20) Immigration History Research Center, University of Minnesota, SVU collection, BOX 2, Circular letter of SVU, 22. September 1961.

21) Lucie FORMANOVÁ – Jiří GRUNTORÁD – Michal PŘIBÁŇ: Exilová periodika. Katalog periodik čes. a slov. exilu a krajanských tisků vydávaných po roce 1945. Ježek, Rychnov nad Kněžnou 1999, pp. 289-292.

22) Michal PŘIBÁŇ: Prvních dvacet let. Kulturní rada a další kapitoly z dějin literárního exilu 1948-1968, pp. 278-279.

23 Miloslav RECHCÍGL: Postavy naší Ameriky, Pražská edice, Praha 2000, p. 303.

24) Lilly Library, University of Indiana, Hlavaty MSS II., BOX 4, Letter of Václav Hlavatý to the members of SVU Board, 1. January 1961.

25) Lilly Library, University of Indiana, Hlavaty MSS II., BOX 4, Letter of Václav Hlavatý to Ladislav Radimský, 2. June 1963.

26) Lilly Library, University of Indiana, Hlavaty MSS II., BOX 4, Letter of Václav Hlavatý to René Wellek,1. November 1963.

27) Lilly Library, University of Indiana, Hlavaty MSS II., BOX 4, Letter of Ivan Herben to Miloslav Rechcígl jr.,18. April 1968.

28) List of Václav Hlavatý´s membership in various academic and scientific bodies below. Prior 1948: Academy of Science (Prague), Royal Society of Science (Prague), Institute of Science (Bucharest), Math Seminar (Moscow); In Exile: Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences (Washington D.C.), Société royale des sciences (Liege), Sigma Xi (Ithaca), Pi Mu Epsilon (Syracuse), Indiana Academy of Science (Indianapolis), Academie Internationale Libre des Sciences et des Lettres (Paris), American Mathematical Society (Providence), Masaryk Fund (Chicago), Académie royale des sciences, des lettres et des beaux-arts de Belgique (Brussels).

About the Contributing Author

Martin Nekola, Ph.D. is a political scientist and historian born in Prague. He studied at Charles University in Prague and was a Fulbright post-doctoral fellow at Columbia University. His research focuses on the Cold War émigrés and the Czech communities in the USA. He is the author of three hundred articles and has published twelve books in the past ten years. He is a member of The Association for Slavic, East European & Eurasian Studies (ASEEES) and the Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences. He works closely with the Bohemian National Hall in New York City and T.G. Masaryk School in Chicago. He is the coordinator of the Czechoslovak Talks project, collecting interesting life stories of Czechs abroad.

*Images and quote inserted by us and are not in any particular order.

Thank you in advance for your support…

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

We appreciate you more than you know!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.