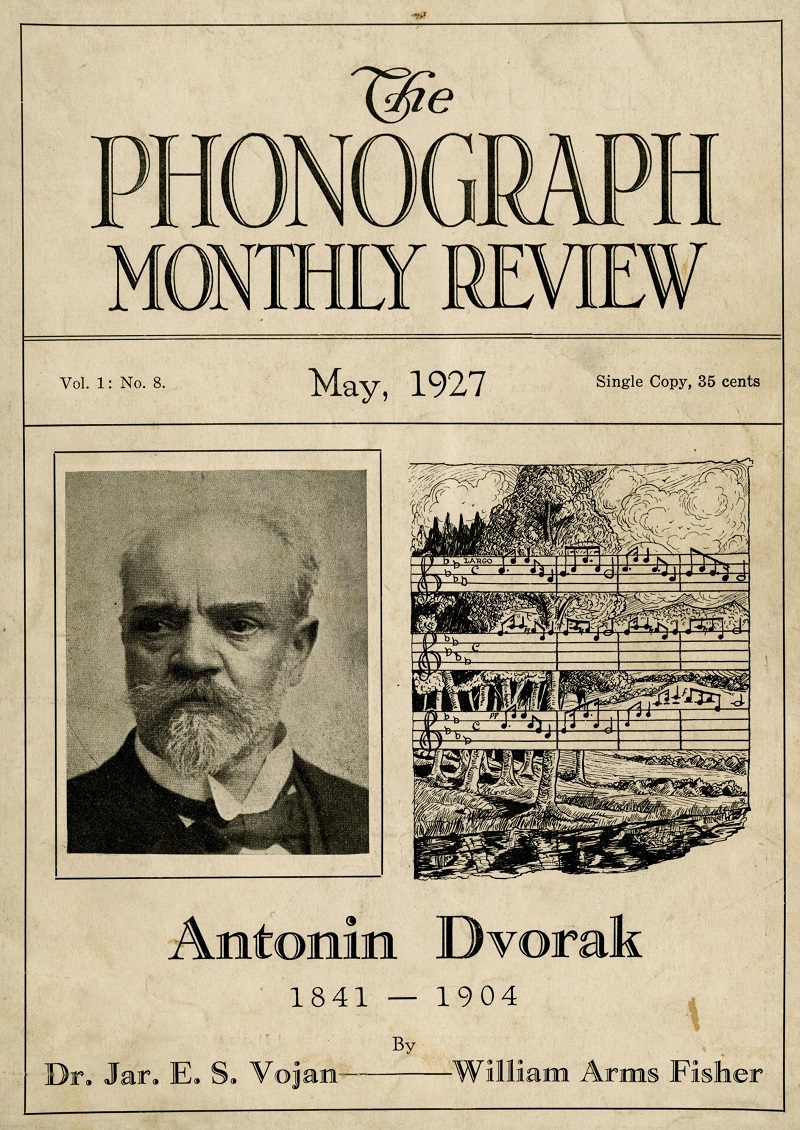

Today’s post is dedicated to the memory of Antonín Dvořák, the great Bohemian composer. America and the Czech Republic (Bohemia) have a warm place in their hearts for Dvorak. Both country’s love him on account of his visit to America, the influence of the works he wrote in America, and for the splendid lesson he had for us through the example of his own great soul and lovable personality. So it is a work of pride and pleasure to attempt in a small way to pay homage to his memory. Our post comes from The Phonograph Monthly Review.

It is a significant proof of the love and respect in which he was held by those who really knew him that two such distinguished authorities as Dr. Jar. E. S. Vojan and Mr. William Arms Fisher were so willing to lend their valuable assistance to us. We are sure that all our readers will share the pleasure we have had in their contributions and join us in thanking these two gentlemen whose friendship for Dvorak does much to keep the kindliness of his nature and the true worth of his genius fresh in our minds.

Those who did not know or truly understand Dvorak will appreciate him better after reading the tributes of his friends, and will be better fitted to hear and understand his works, which the phonograph brings to the homes of all of us today.

Antonín Dvořák

HANS SACHS sings in Wagner’s “Mastersingers of Nuremberg”: “Then sang he (Walther von Stolzing) as Nature bade; and to his need the power was granted from her dower” (the original says it in a much better, lapidary style : “Nun sang er, wie er musst’ ; und wie er musst’, so konnt’ er’s.”). And in these words is the entire story of Antonín Dvořák. Although without any better education than a village school could give him, he gave to the world’s music immortal symphonies, chamber music works and oratorios.

America is indebted to him forever for the best symphony ever written in this country, the splendid symphony “From the New World.” For the history of the modern Bohemian music Dvorak means the completion of Smetana’s work: Smetana wrote monumental operas and symphonic poems, Dvorak wrote monumental symphonies, oratorios and chamber music works.

Dvorak was born at Nelahozeves upon Vltava, a small village not far from Prague, on September 8, 1841. His father Frank was the village butcher and innkeeper who after 13 years moved to Zlonice, a little town where Antonín found a good music teacher in the old schoolmaster Antonin Liehmann who taught him elementary theory, violin, viola, piano and organ playing. He called his father’s attention to the great talent of Antonin, but—the financial conditions of the innkeeper were so bad that he could not make any other decision than to make the son his successor. So Antonin became a butcher’s apprentice for one year, until Liehmann’s insistence and an uncle’s promise of aid changed the situation. The father allowed Antonin to go to Prague, and in the fall of 1857 the 16-year old boy entered the organschool in Prague. “The fate which gave the world a composer of music robbed Bohemia of a butcher,” says H. E. Krehbiel.

In Prague Dvorak kept himself alive by playing the viola in Komzak’s private band which in 1862 became the nucleus of the Interim Theatre orchestra, the conductor of which Smetana became four years later. From 1862 Dvorak began to compose, but he did not venture before the public until 1873, when he made his first bid for popularity by a patriotic cantata “Dědicové Bílé hory” (The Heirs of the White Mountain,—the name of the battlefield where Bohemia lost her independence in 1620). The same year Dvorak married his pupil Miss Anna Cermak (she survived her husband and is still living in Prague) and became organist of St. Vojtech’s church.

In February, 1875, a brighter star appeared in the sky for the striving composer. He received 400 florins ($160 at that time) from the governmental fund for the encouragement of poor, talented composers. The main thing, however, was the interest which his music had awakened in three members of the jury, composer Johannes Brahms, critic Dr. Eduard Hanslick and conductor of the Vienna Opera Johann Herbeck.

Brahms recommended Dvorak’s works to his publisher Simrock in Berlin, and the first composition published in 1877 by Simrock, “Slavonic Dances,” took the public by storm. These pianoforte duets, full of glittering melody and rhythm, ravished Germany and England and in orchestral form found their way into the concert halls of Berlin, London and New York (here Theodore Thomas brought them forward in the winter of 1879-1880). Dvorak’s name became known to the entire musical world.

On March 10, 1883, the London Musical Society performed Dvorak’s oratorio “Stabat Mater.” The work created a veritable sensation, which was intensified by a repetition under the direction of Dvorak himself three days later, and by a performance at the Worcester festival in 1884.

Dvorak now became the idol of the English choral festivals. In 1885 he composed “Svatebni kosile” (The Spectre’s Bride) for Birmingham, in 1886 “St. Ludmila” for Leeds, in 1891 the “Requiem” for Birmingham. The composer who in the seventies found it pretty hard to pay 2 florins a month for the rent of a poor piano now won newer and newer triumphs. The greatest conductors like Hans Richter and Hans Buelow in Germany, Seidl in New York, Nikisch in Boston and Thomas in Chicago, performed his symphonical compositions, the famous Joachim String Quartet played his chamber music works, and in 1891, on Dvorak’s fiftieth birthday, the University of Cambridge in England conferred on him the degree of doctor of music, then the Bohemian University in Prague followed with the honorary title of doctor of philosophy, and the government of Austria with the elevation to the Austrian House of Peers.

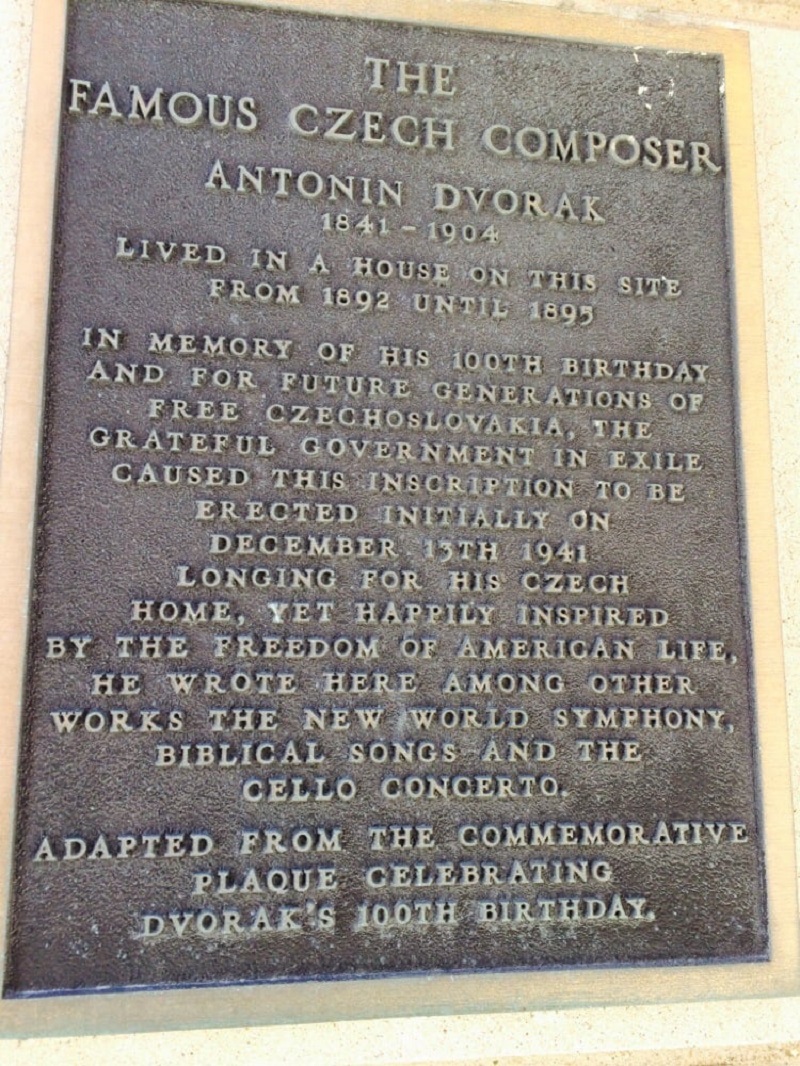

In 1892 Dvorak came to America. He was called to New York as director of the National Conservatory of Music for three years, at a salary of $15,000 a year, a sum undreamed of by European composers of those days. He arrived on September 26, and on October 21, 1892, the first concert to his honor was given at the Music Hall in New York. Dvorak conducted personally his three ouvertures “Nature, Love, Life” (today known under the names “In the Nature,” “Cthello” and “Carneval”) and his “Te Deum.”

[Our insertion: Dvořák’s New York home was located at 327 East 17th Street, near the intersection of what is today called Perlman Place. It was in this house that both the B minor Cello Concerto and the New World Symphony were written within a few years. Despite protests, from Czech President Václav Havel amongst others, who wanted the house preserved as a historical site, it was demolished in 1991 to make room for a Beth Israel Medical Center residence for people with AIDS.]

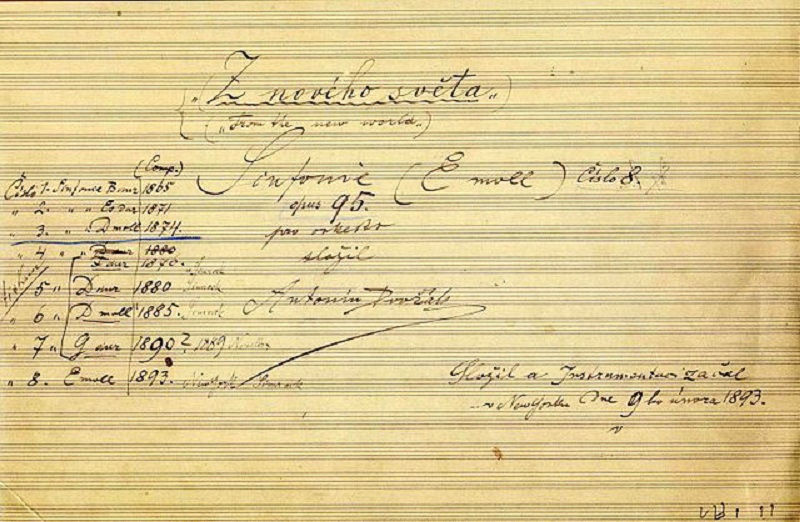

“Morning, December 19, 1892” is the date of the first sketch in Dvorak’s sketchbook for the symphony “From the New World.” Dvorak dated carefully all his sketches and compositions, and therefore we know perfectly when they were begun and finished.

The complete sketch was made from January 10 to May 12, 1893, the full score was finished as follows : the first movement February 28, the second March 14, the third April 10 and the fourth May 24, 1893, all in New York.

As to the well known controversy whether this work was inspired by America or not, and whether Dvorak used any American aboriginal and Negro themes, Dvorak himself is the judge. He wrote to Dr. Emil Kozanek in Olomouc, Moravia, under the date of September 15, 1893:

I know that my new symphony and the string quartet in F major and the quintet would never have been so written if I had not seen America.

And in March, 1900, he wrote to Nedbal when this conductor was to perform his New World Symphony in Berlin:

I send you Kretschmar’s analytical booklet, but please omit the nonsense that I have used Indian and American motives, because it is a lie. I tried only to write in the spirit of American folk melodies.

The unrivaled popularity of this symphony in America proves that he succeeded. The Symphony No. 5, E minor or “From the New World” was given its first performance in New York, by the Philharmonic Society, with Anton Seidl conducting and Dvorak present.

The other American compositions were written partly in New York, partly at Spillville, Iowa, where Dvorak spent his summer vacations in 1893 with his family among the Bohemian population of that village. To these American compositions—besides the Symphony op. 95—belong the following works: String Quartet F major, op. 96 (June, 1893, Spillville), Quintet E flat major, op. 97 (July, August, 1893, Spillville), cantata “The American Banner,” Suite for piano, op. 98 (February, 1894, New York), “Biblical Songs,” op. 99 (March, 1894, New York), Sonatina G major for violin and piano, op. 100 (November, 1893, dedicated to Dvorak’s children Otylia and Antonín who were with their father in New York,—Otylia became later the wife of the Bohemian composer Josef Suk, but she died too early), “Humoresky” for piano, op. 101 (the seventh of these eight small compositions is the world famous “Humoresque”), “Berceuse” and

Concerto for Violoncello, op. 104.

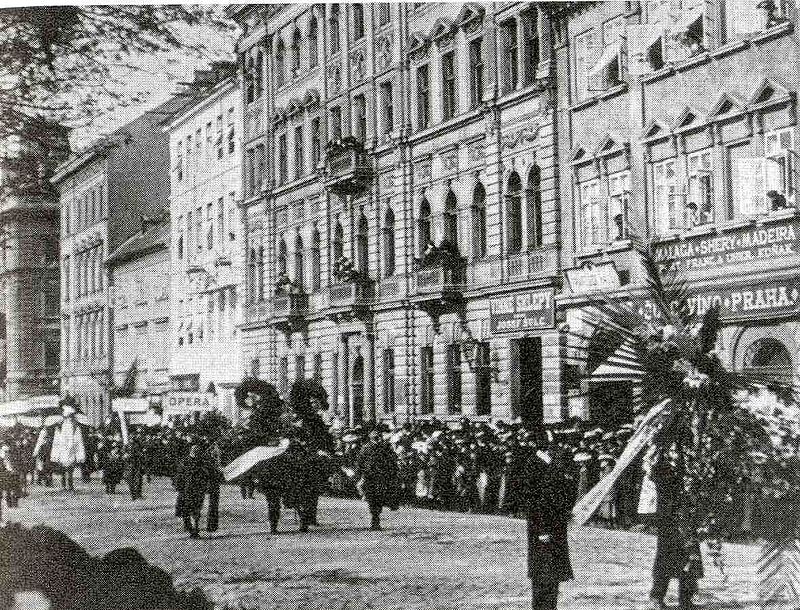

After his return to Bohemia, Dvorak became again professor of composition at the Conservatory of Prague which elected him to the office of director in 1901. He remained at this post until his death on May 1, 1904.

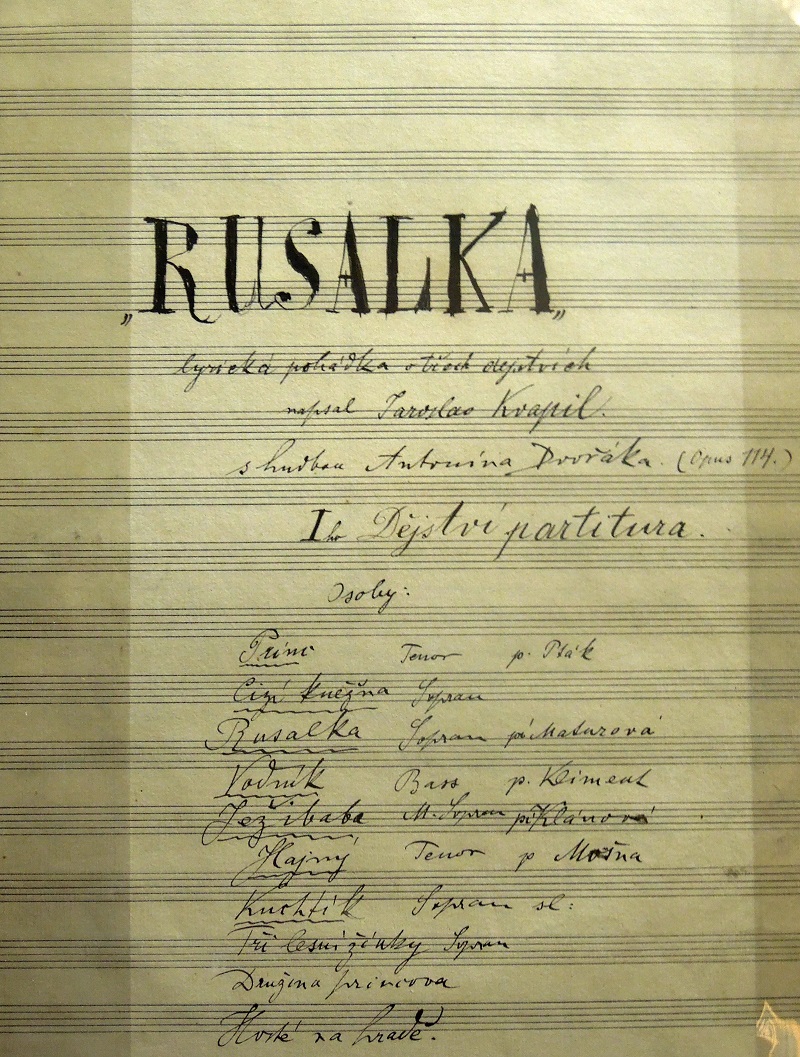

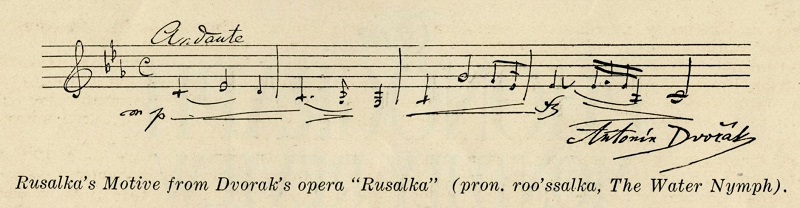

His bequest contains more than 120 works. Among them are seven symphonies, several symphonic poems, symphonic overtures, 30 chamber music works, concertos for violin, violoncello, pianoforte works (some of them were later arranged for the orchestra by Dvorak himself, like “Slavonic Dances” and “Legends,”—Brahms esteemed his brilliant art of orchestration so highly that he asked him to orchestrate his “Hungarian Dances”), songs, choruses, cantatas, oratorios, operas the best of which are “Rusalka” (The Water Nymph), “Jakobin” (The Jacobin), “Dimitrij” (its story begins where Moussorgski’s “Boris Godunov” ends), etc.

Characteristic rhythms and charming harmonic effects as well as bright and glittering instrumentation are significant of the works of Dvorak who was one of the most original composers of the world in the realm of absolute music.

In private life Dvorak remained a plain man till his death. He is the only Bohemian composer from whose life hundreds and hundreds of anecdotes are related. I will mention only three of them.

His was a simple, deep faith, free from dogmatical shade. Once when he returned from a visit to Brahms whom he adored, he was very sad. Asked why, he replied: “Don’t you understand? Brahms, such a big and dear man,—and he believes in nothing, absolutely in nothing!”

When a critic asked him what his relations to Tchaikowski were, he said: “That’s simple! I don’t like Tchaikowski’s music, and Tchaikowski does not like my music!”

And in connection with the present Beethoven memorial days: On one occasion his admirers gave him a big wreath with a ribbon which bore the inscription: “To the greatest genius!” He took it home and hung it—around Beethoven’s portrait.

[My addition: Both Bedřich Smetana and Antonín Dvořák exclaimed a great appreciation towards František Matěj Hilmar’s compositions. They held him as a peer and regarded the composer’s work in the highest esteem. Read more about the father of the polka who composed over 1,000 pieces of music.]

Dvorak did not write any articles for musical magazines. But there is a remarkable article, today entirely forgotten, which you can find in the “Harper’s New Monthly Magazine,” vol. XC, No. 537, pp. 429-434. The title is “Music in America by Antonín Dvořák.” The footnote says: “The author acknowledges the co-operation of Mr. Edwin Emerson, Jr., in the preparation of this article.” When sixteen years ago I translated this article into Bohemian and printed it in the “Hudebni Revue” (Musical Review, Prague), all Dvorak experts agreed that there was no doubt about Dvorak’s authorship of this article. The form belongs to the American essayist, but the contents show clearly the ideas of Dvorak well known to all who were his intimate friends. The translation was sincerely greeted in Prague, because Dvorak’s written statements about musical and esthetic matters are very rare.

The article was written in the first part of March, 1894, because in the seventh paragraph of the essay we read : “Since the days of Palestrina, the three-hundredth anniversary of whose death was celebrated in Rome a few weeks ago,” and that anniversary was on February 2, 1894. It was the second year of Dvorak’s directorship in New York. I will quote here only two last paragraphs of the valuable article:

“My own duty as a teacher, I conceive, is not so much to interpret Beethoven, Wagner, or other masters of the past, but to give what encouragement I can to the young musicians of America. I must give full expression to my firm conviction, and to the hope that just as this nation has already surpassed so many others in marvellous inventions and feats of engineering and commerce, and has made an honorable place for itself in literature in one short century, so it must assert itself in the other arts, and especially in the art of music. Already there are enough public-spirited lovers of music striving for the advancement of this their chosen art to give rise to the hope that the United States of America will soon emulate the older countries in smoothing the thorny path of the artist and musician. When that beginning has been made, when no large city is without its public opera-house and concert-hall, and without its school of music and endowed orchestra, where native musicians can be heard and judged, then those who hitherto have had no opportunity to reveal their talent will come forth and compete with one another, till a real genius emerges from their number, who will be as thoroughly representative of his country as Wagner and Weber are of Germany, or Chopin of Poland. To bring about this result we must trust to the ever-youthful enthusiasm and patriotism of this country. When it is accomplished, and when music has been established as one of the reigning arts of the land, another wreath of fame and glory will be added to the country which earned its name, the “Land of Freedom,” by unshackling her slaves at the price of her own blood.”

Dvořák Recordings

SYMPHONY NO. 5 “FROM THE NEW WORLD,” E MINOR

Complete :

Victor 6565-6589 — The Philadelphia Orchestra. Leopold Stokowski, Conductor (electrically recorded).

Columbia Master works, Set No. 3 — The Halle Orchestra in Manchester. Sir Hamilton Harty.

Excerpts: Largo, Victor 6236 — Philadelphia Orchestra.

“Going Home,” a theme from Largo, paraphrased by Fisher: Brunswick 30113, Mario Chamlee, and 3127, Brunswick Concert Orchestra

Victor 6472 — Werrenrath.

Kreisler, Negro Spiritual Melody (also a theme from Dvorak’s Symphony), Victor 1122 — Kreisler.

CARNEVAL OUVERTURE

Victor 6560— Chicago Symphony Orchestra. Fred Stock.

SLAVONIC DANCES

(Originally as Piano Duets, Op. 46, Nos. 1-8, Op. 72, Nos. 9-16. Orchestrated by Dvorak himself, but the publisher changed two numbers, making the original No. 6 now No. 3 and vice versa).

No. 1. Victor 35715 — Victor Concert Orchestra. Victor 35507 — Vessella’s Italian Band.

No. 2. Victor 35715 — Victor Concert Orchestra.

No. 3. (Orchestrated No. 6) Odeon 5011 — German Opera House Orchestra, Berlin, Eduard Moericke.

No. 6. (Orchestrated No. 3) Brunswick 15091 — Cleveland Orchestra. Nikolai Sokoloff.

No. 7. Victor 16202 — Prague Military Band.

No. 8. Odeon 5011 — German Opera House Orchestra. Moericke. (The same Ncs. 3 and 8 also Parlophone, P 1152.)

Arrangements for Violin and Piano:

No. 2. Kreisler ’s No. 1, G minor (only one-half is Dvorak, the other half is Kreisler).

Victor 723 — Kreisler.

Victor 675 — Heifetz.

Victor 976 — Thibaud.

Polydor 14785 — Jenny Skolnik.

Nos. 6 and 7. Polydor 65979 — Adolf Busch.

No. 10. Kreisler ’s No. 2, E minor.

Victor 6183 — Kreisler.

Victor 6376 — Heifetz.

Columbia 9001 -M — Seidel.

Polydor 6598-Prihoda.

No. 15. Polydor 65994 — Prihoda.

No. 16. Kreisler’s No. 3, G major.

Victor 6376 — Heifetz.

ROMANTIC PIECES

Adagio. Polydor 62469 — Adolf Busch.

WALTZES

No. 1, A major. Polydor 66219 — Prihoda.

DUMKY TRIO

Polydor 66194, 66195, and 66196 — Pozniak Trio.

Columbia 67090-D — Catterall, Murdoch and Squire. (Just the only part which was omitted by Pozniak Trio, therefore these four records make the Trio complete).

HUMORESQUE

(No. 7 from Humoreskv, Op. 101, Nos. 1-8, written for piano solo.)

Arrangements, Violin and Piano:

Victor 6181 — Kreisler.

Victor 6095 — Elman.

Columbia 9028-M and 9003-M — Seidel.

Polydor 66187 — Prihoda.

Polydor 65979 — Busch.

Brunswick 20019 — Fradkin.

Brunswick 50005 — Rosen.

Other arrangements:

Victor 45165 — Victor Herbert Orchestra.

Victor 20130 — Venetian Trio.

Columbia 846-D — Squire’s Octette.

Parlophone P 1253 — Marek Weber.

INDIAN LAMENT

(Second movement of the Sonatina G major, Op. 100, for Violin and Piano; Simrock called this movement “Canzonetta,” Kreisler baptized it “Indian Lament”.)

Victor 6186 — Kreisler.

Polydor 66058 — Prihoda.

Homokord 8142 — Fuchs.

TYROLEAN DANCE

(An entirely false and nonsensical name for Scherzo of the same Sonatina, Op. 100.)

Victor 17934 — Natalie and Victoria Boshko.

QUARTET F MAJOR, OP. 96

Lento. Victor 6449 — Flonzaley Quartet.

Lento and Scherzo. Brunswick 25015 — New York String Quartet.

Finale. Polydor 66421 — Amar Quartet.

QUARTET E FLAT MAJOR, OP. 51

Dumka and Romanza — Polydor 19020 — Post Quartet.

GYPSY SONGS, OP. 55, NO. 1.

No. 1. I chant a hymn of love — Gramophone Company, Ltd. 2-72228 Vand 67-F — Otokar Marak, in Bohemian.

No. 4. Songs my mother taught me.

Victor 622 — Geraldine Farrar, in English.

Victor 73360 — Milo Luka, in Bohemian.

Columbia 41185 and 67-F — Otokar Marak, in Bohemian.

Columbia 103-M — Barbara Maurel, in English.

Brunswick 10116 — Florence Easton.

Kreisler’s violin arrangement:

Victor 727 — Kreisler.

Brunswick 10175 — Elshuco Trio.

BIBLICAL SONGS, OP. 99. NO. 7

By the Waters of Babylon. Victor 68271 — Janpolski, in German.

FOUR SONGS IN FOLK TONE, OP. 73, NO. 2

Amowing stood a lovely maid. Victor 87324 — Emmy Destinn, in Bohemian.

Operas:

THE SLY PEASANT

Air of the Prince. Victor 16207 — Bohumil Benoni, in Bohemian.

DIMITRI

Air of Dimitri. Gramophone Company, Ltd., 2-82216 — Karel Burian, in Bohemian.

RUSALKA (Water-Nymph)

Air of Rusalka, “Oh lovely moon”. Victor 88519 — Emmy Destinn, in German.

Air of the Prince, “Oh strange vision”. Gramophone Company, Ltd., 2-72008 — Otokar Marak; V-4-102529 — Fr. Pacal, both in Bohemian.

SYMPHONY FROM THE NEW WORLD

H.M.V. D 536, 537, 587, 613 — Sir Landon Ronald and Royal Albert Hall Orchestra.

CARNEVAL OVERTURE

H.M.V. D 1062 — Ronald and the Royal Albert Hall Orchestra (Electric).

QUARTET IN F MAJOR

Complete

Victor 9069-71 — Budapest String Quartet (Electric).

Vox 0655-7 — Bohemian String Quartet.

Vocalion — London String Quartet.

Lento alone.

English Columbia L 1465 — Lener String Quartet.

SLAVONIC DANCES

No. 8 (mislabeled No. 1).

Victor 6649 — Chicago Symphony, Frederick Stock, conductor (Electric).

VIOLONCELLO CONCERTO

(In 2 parts only.)

Parlophone E 10482 — Teuermann.

GYPSY SONGS

Songs My Mother Taught Me.

Victor 20494 — Associated Glee Clubs cf America (Electric).

H.M.V. DB 363— Nellie Melba,

HUMORESKE

No. 7, Piano.

Victor 20203 — Hans Barth (Electric).

H.M.V. E 13 — Mark Hambourg.

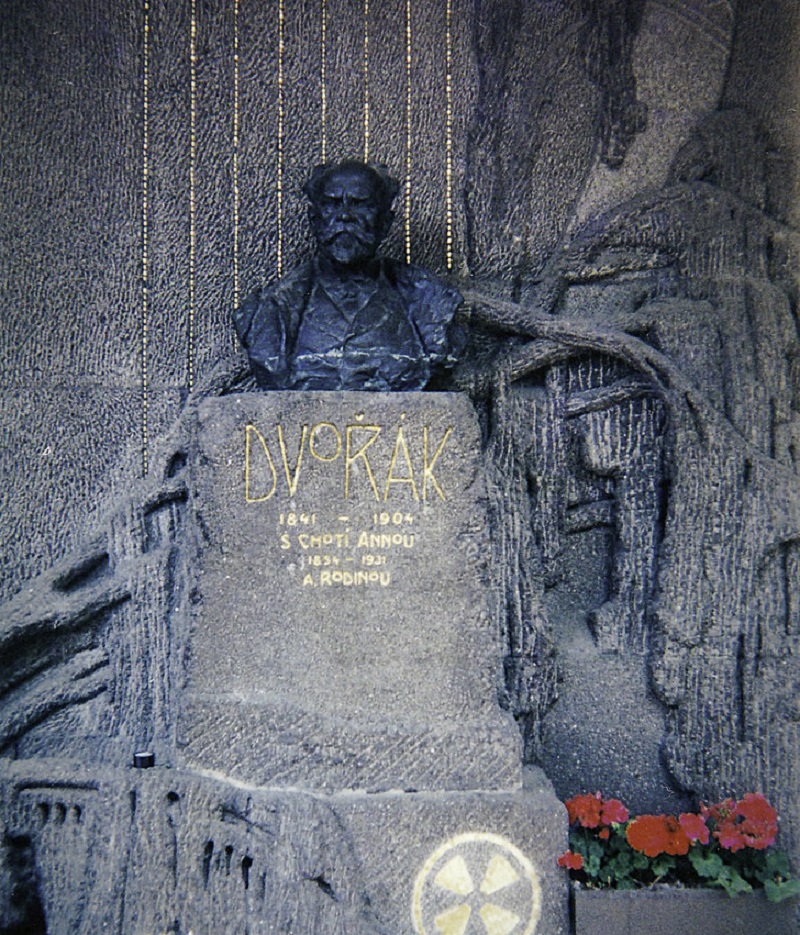

When we were in Prague this past spring, we went to visit his grave and to the National Theater to see Ruslaka (again).

This article was originally published in the Phonograph Monthly Review, Vol. 1, No. 8. Published May 1927. It was written by Dr. Jaroslav Egon Salaba Vojan and Mr. William Arms Fisher.

[Note: At times we write Dvorak and other times Dvořák, we do this for search engine purposes and thank you in advance for overlooking this inconsistency. It is done with good reason.]

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Thank you in advance!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.