The Brundibar Opera is a children’s opera by Jewish Czech composer Hans Krása with a libretto by Adolf Hoffmeister, made most famous by performances by the children of Theresienstadt concentration camp (Terezín) in occupied Czechoslovakia. The name comes from a Czech colloquialism for a bumblebee.

Krása and Hoffmeister wrote the opera in 1938 for a government competition, but the competition was later cancelled because of political developments. Rehearsals started in 1941 at the Jewish orphanage in Prague, which served a temporary educational facility for children separated from their parents by the war.

In the winter of 1942 the opera was first performed at the orphanage: by this time, composer Krása and set designer František Zelenka had already been transported to Theresienstadt. By July 1943, nearly all the children of the original chorus and the orphanage staff had also been transported to Theresienstadt. Only the librettist Hoffmeister was able to escape Prague in time.

Reunited with the cast in Theresienstadt, Krása reconstructed the full score of the opera, based on memory and the partial piano score that remained in his hands, adapting it to suit the musical instruments available in the camp: flute, clarinet, guitar, accordion, piano, percussion, four violins, a cello and a double bass. A set was once again designed by František Zelenka, formerly a stage manager at the Czech National Theatre. They painted several flats as a background, in the foreground was a fence with drawings of the cat, dog and sparrow and holes for the singers to insert their heads in place of the animals’ heads. On 23 September 1943, Brundibár premiered in Theresienstadt. The production was directed by Zelenka and choreographed by Camilla Rosenbaum, and was shown 55 times in the following year.

A special performance of Brundibár was staged in 1944 for representatives of the Red Cross who came to inspect living conditions in the camp; what the Red Cross did not know at the time was that much of what they saw during their visit was a show, and that one reason the Theresienstadt camp seemed comfortable was that many of the residents had been deported to Auschwitz to reduce crowding during their visit.

Later that year this Brundibár production was filmed for a Nazi propaganda film Theresienstadt: ein Dokumentarfilm aus dem jüdischen Siedlungsgebiet (Theresienstadt: a documentary film from the Jewish settlement area). All the participants in the Theresienstadt production were herded into cattle trucks and sent to Auschwitz as soon as they finished filming. Most were gassed immediately upon arrival, including the children, the composer Krása, the director Kurt Gerron, and the musicians.

The Brundibar Opera footage from the film is included in the Emmy Award-winning documentary Voices of the Children directed by Zuzana Justman, a Terezin survivor, who sang in the chorus. Ela Weissberger, who played the part of the cat appears in the film. The footage appears again in As Seen Through These Eyes, a 2009 documentary directed by Hilary Helstein. There Weissberger describes the opera in some detail, noting that the only time that the children could remove their yellow stars was during a performance.

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=eq4MsEuAeP8

The final verse from A. Hoffmeister’s song was: “Who likes mummy with his father and our native land is our friend and is allowed to play with us.” Erik A. Saudek rewrote the opera in the Terezin ghetto: “Who has the right he likes to live and he is not afraid … ” The final lyrics became a kind of Terezín anthem. The actors and the audience knew very well what these words meant, along with the fight of innocent children against the evil Brundibar.

Below is some rare footage from the end of Hans Krása’s opera for children, Brundibár, as performed at the Terezín transit camp in 1943.

The plot of the opera shares elements with fairytales such as Hansel and Gretel and The Town Musicians of Bremen. Aninka and Pepíček are a fatherless sister and brother. Their mother is ill, and the doctor tells them she needs milk to recover. But they have no money. They sing in the marketplace to raise the needed money.

But the evil organ grinder Brundibár (of this figure Iván Fischer has said, “Everyone knew he represented Hitler”) chases them away. However, with the help of a fearless sparrow, keen cat, and wise dog, and the children of the town, they can chase Brundibár away, and sing in the market square.

The Brundibar Opera contains obvious symbolism in the triumph of the helpless and needy children over the tyrannical organ grinder, but has no overt references to the conditions under which it was written and performed. However, certain phrases were to the audience clearly anti-Nazi. Though Hoffmeister wrote the libretto before Hitler’s invasion, at least one line was changed by poet Emil Saudek at Terezin, to emphasize the anti-Nazi message. “While the original said,’He who loves so much his mother and father and his native land is our friend and he can play with us,’ Saudek’s version reads: ‘He who loves justice and will abide by it, and who is not afraid, is our friend and can play with us”.

So how did the Nazis kill millions of Jews and keep so much of the world in the dark? We can find part of the answer when looking at the history of a concentration camp called Theresienstadt (Terezin), in what was Czechoslovakia. Near the end of the war, the Nazis used the camp to con the world. Yes, con the world.

Reports had circulated in Allied capitals that the Nazis were exterminating Jews. The Nazis wanted to refute those reports, so they took this one camp and turned it, if ever so briefly, into a model town. They shot a movie there to prove how well they treated the Jews and invited the Red Cross to inspect it.

Central to the deception was the performance of a children’s opera called Brundibar. The Brundibar Opera and a few members of its cast survived the war. They are in their mid-80s now, and in 2007, they invited 60 Minutes correspondent Bob Simon to spend some time with them. (Bob Simon was killed in a car crash on February 2015. He was 73.)

If you are a CBS subscriber or your cable plan allows it, you can also watch Bob’s interview with the survivors here.

Bringing it Around Again

The sun eventually smiles, and the mustachioed bad guy gets his comeuppance in “Brundibar,” the opera for children that opened May 8, 2006, at the New Victory Theater. But as we know too well, the story behind this little musical charmer does not include many happy endings.

This sad, freighted history is a large burden for a little opera to bear, but it does not cast too long a shadow on the New Victory. Tony Kushner, who has provided a new English libretto for this production (the original is by Adolf Hoffmeister), describes the opera’s provenance in the program. He has also written a small play, “But the Giraffe,” that is performed before “Brundibar” and gently colors in the historical context. We can use this production as a soft point of entry for children old enough to grapple with the history of the Holocaust.

Read the entire article and review of the Brundibar Opera performance here.

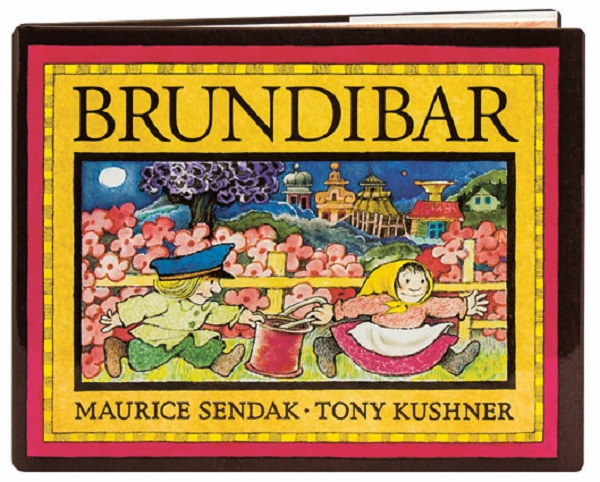

Finally, pick up a copy of Maurice Sendek’s Brundibar, a brilliant and disturbing rendition of an old Czech opera that honors history in a stunning piece of art. A small brother and sister need money to buy milk for their sick mother, but singing in the town square is impossible because bully Brundibar claims the territory. Adults throwing money at Brundibar’s “bellowing” can’t hear Pepicek and Aninku at all; when the children challenge him by turning briefly into bears, the masses declare, “Call the cop!” and “No bears on the square! It’s the law!” Brundibar’s alarming song gets louder and scarier until Pepicek and Aninku run away. They hide in a gloomy alley until 300 children arrive and help them triumph over evil Brundibar.

You can listen to Maurice Sendak on Adapting ‘Brundibar’ for Theater here.

Today, we remember these people and honor the survivors of the Brundibar Opera…

We tirelessly gather and curate valuable information that could take you hours, days, or even months to find elsewhere. Our mission is to simplify your access to the best of our heritage. If you appreciate our efforts, please consider donating to support this site’s operational costs.

See My Exclusive Content and Follow Me on Patreon

You can also send cash, checks, money orders, or support by buying Kytka’s books.

Your contribution sustains us and allows us to continue sharing our rich cultural heritage.

Remember, your donations are our lifeline.

If you haven’t already, subscribe to TresBohemes.com below to receive our newsletter directly in your inbox and never miss out.