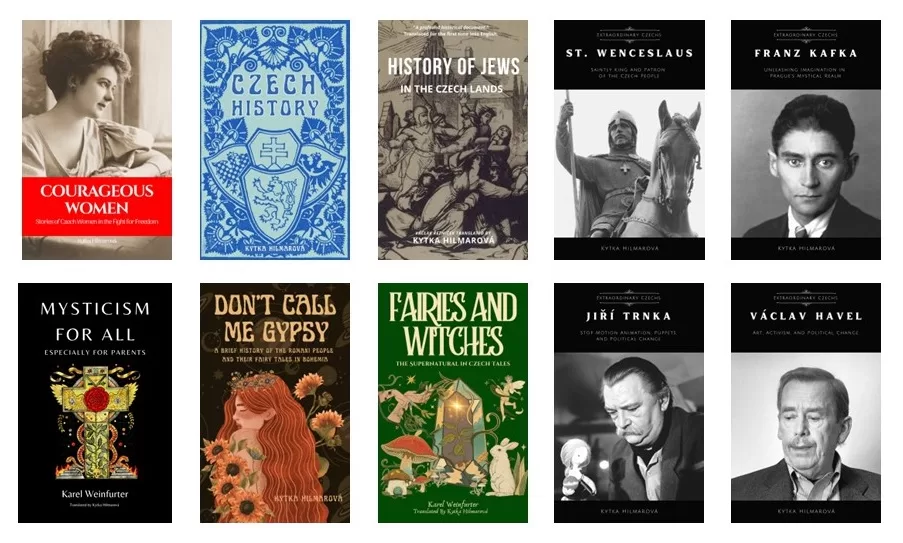

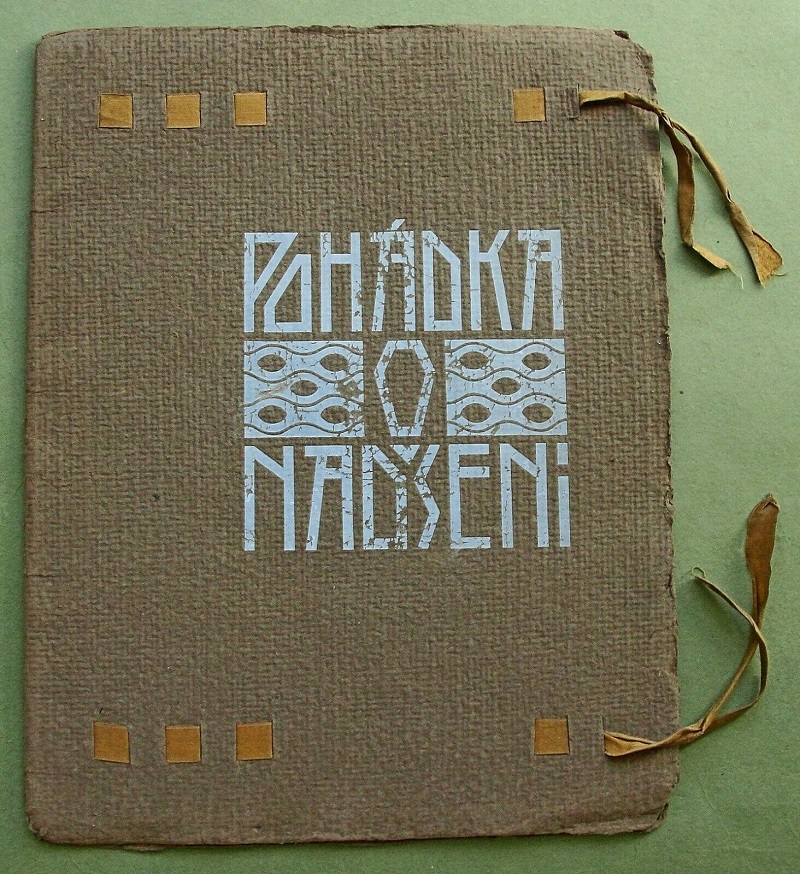

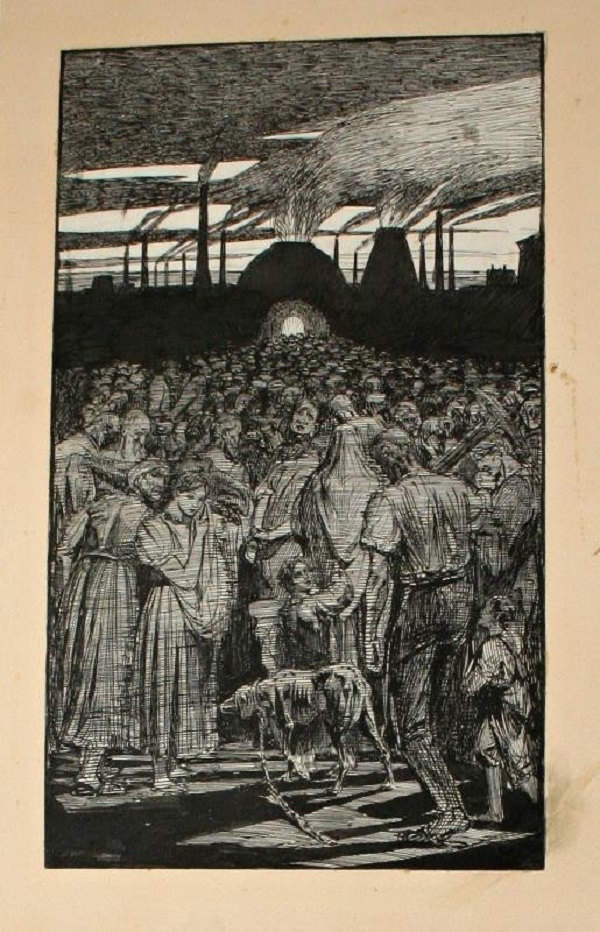

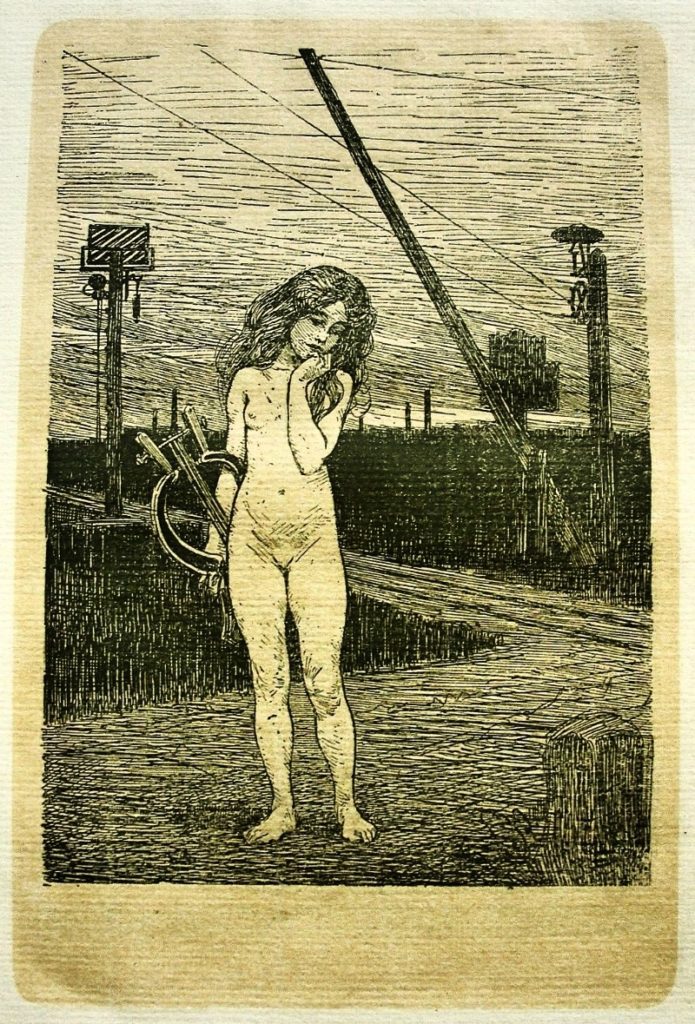

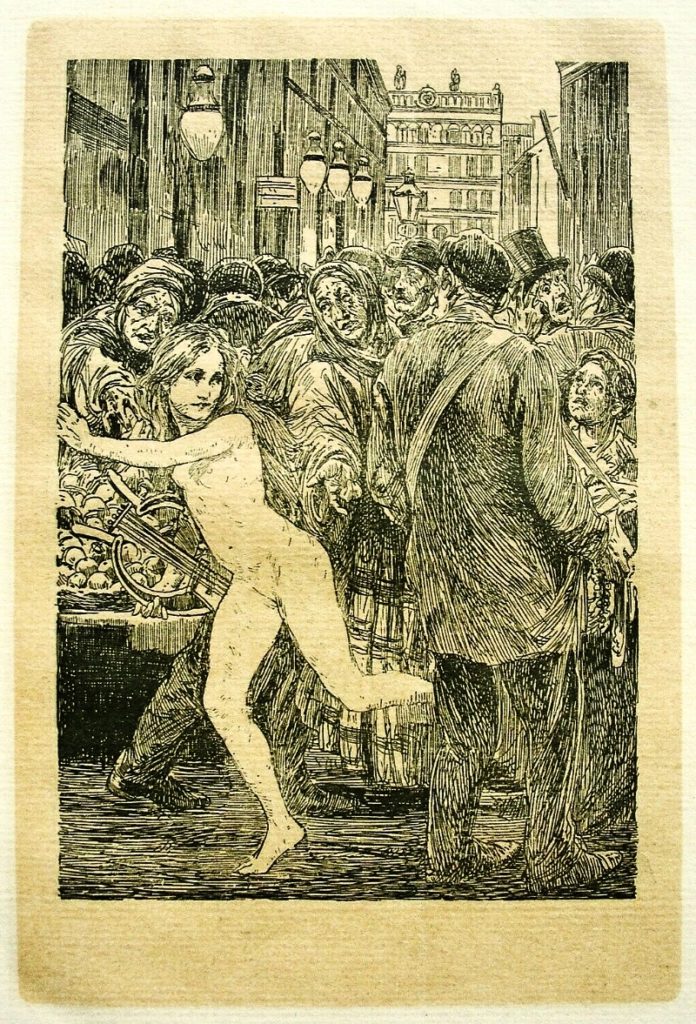

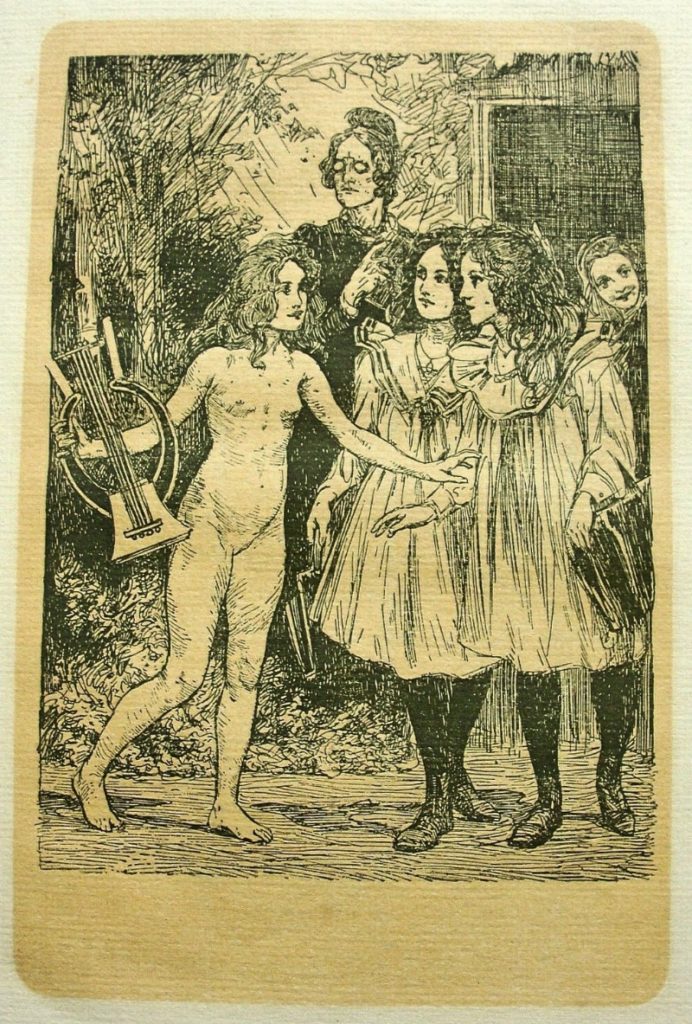

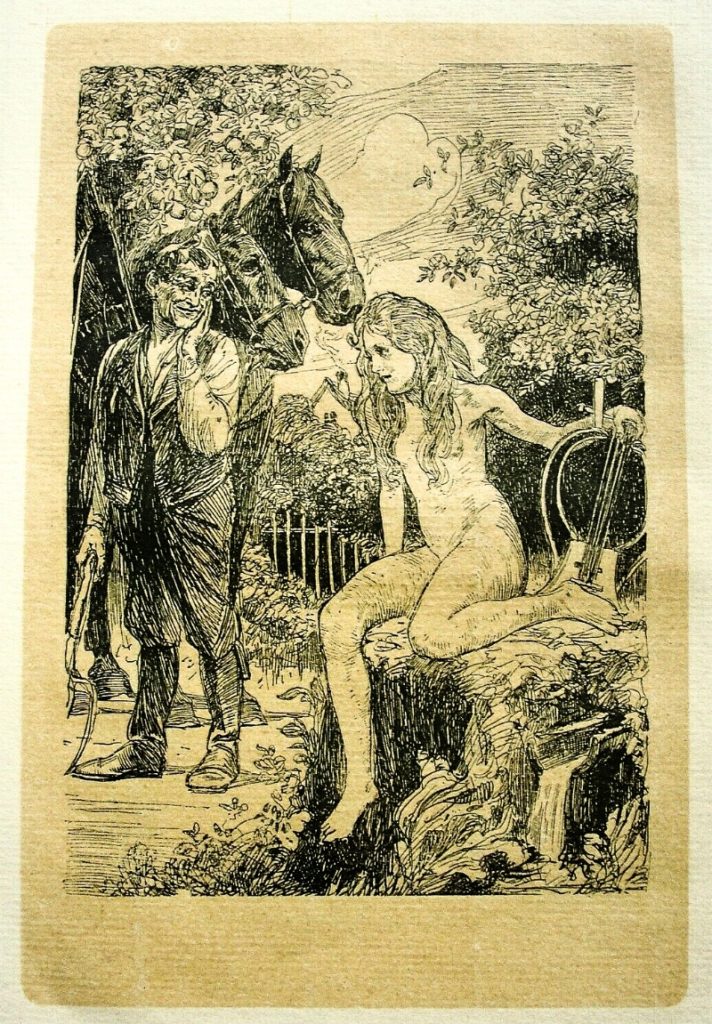

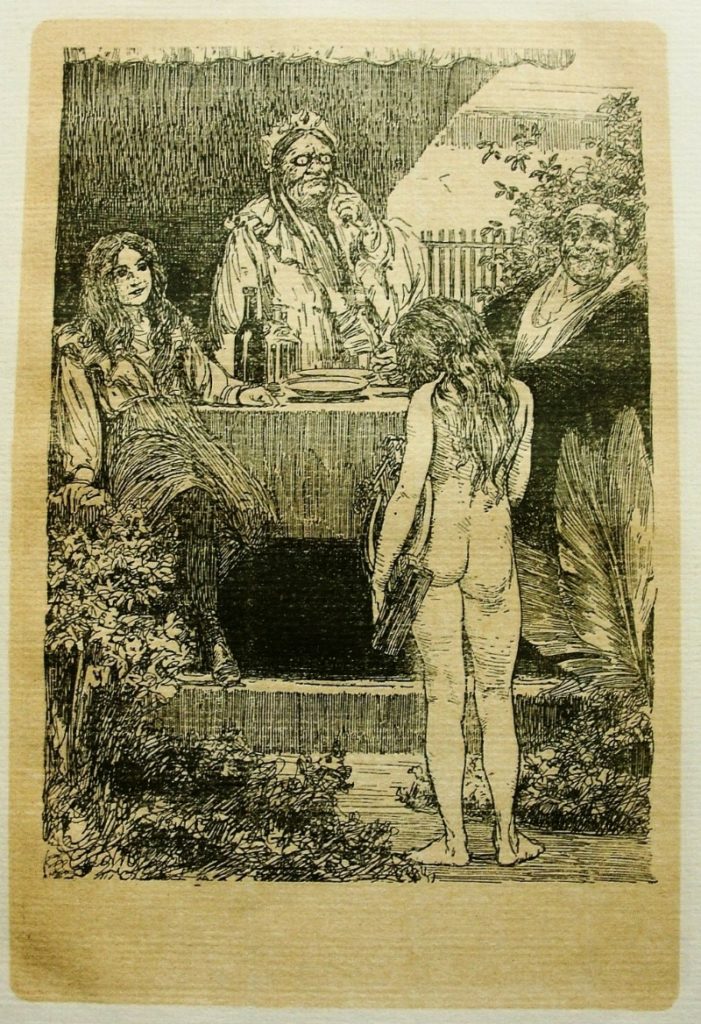

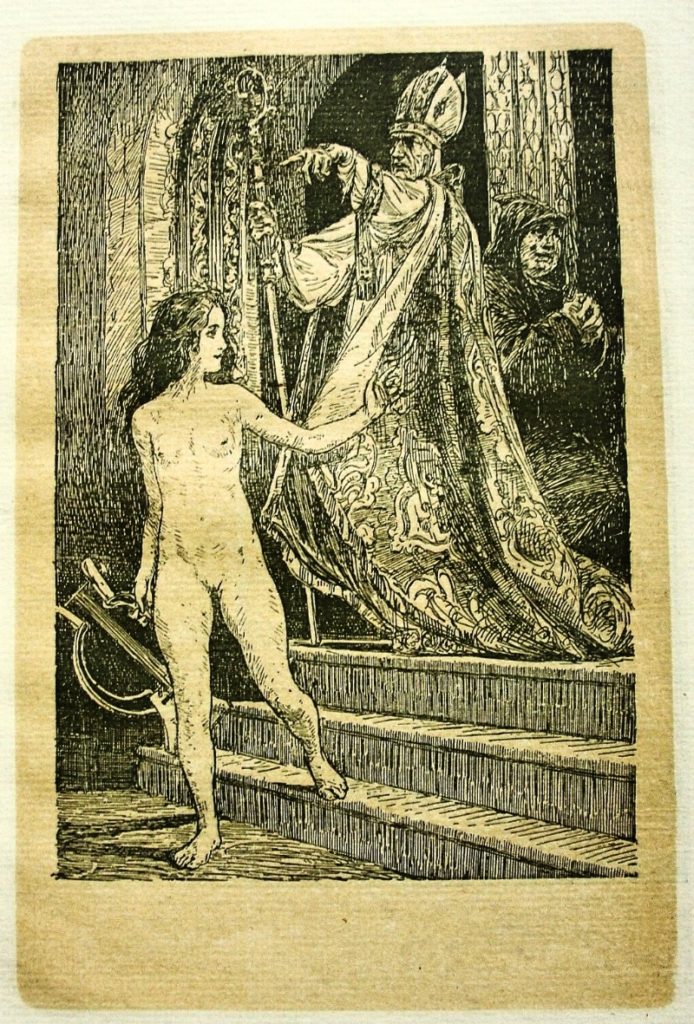

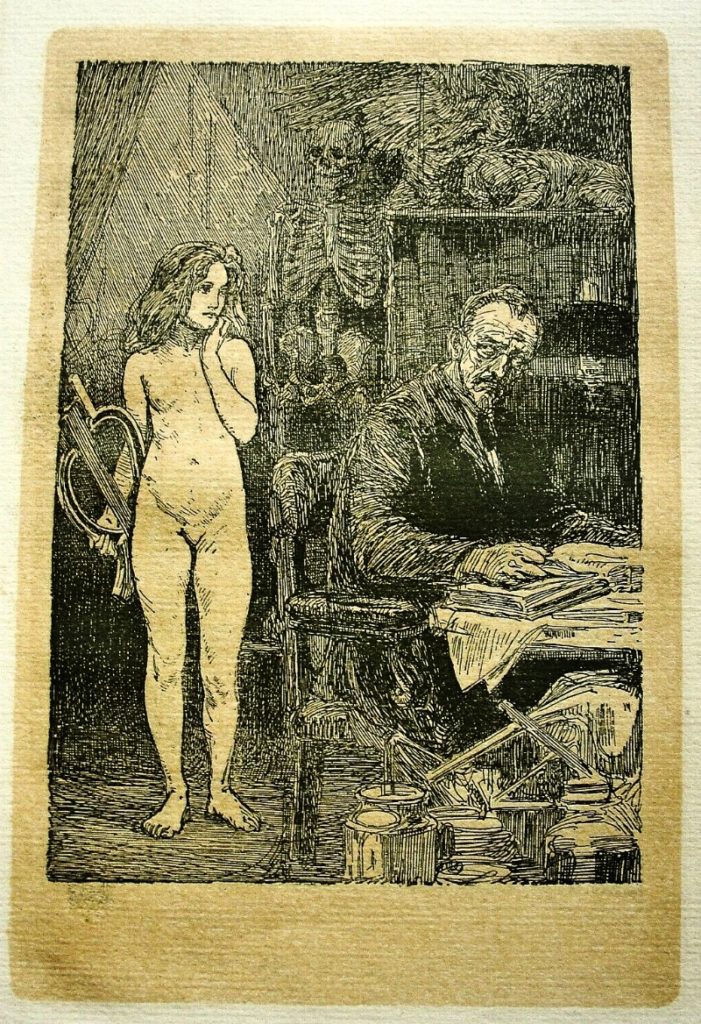

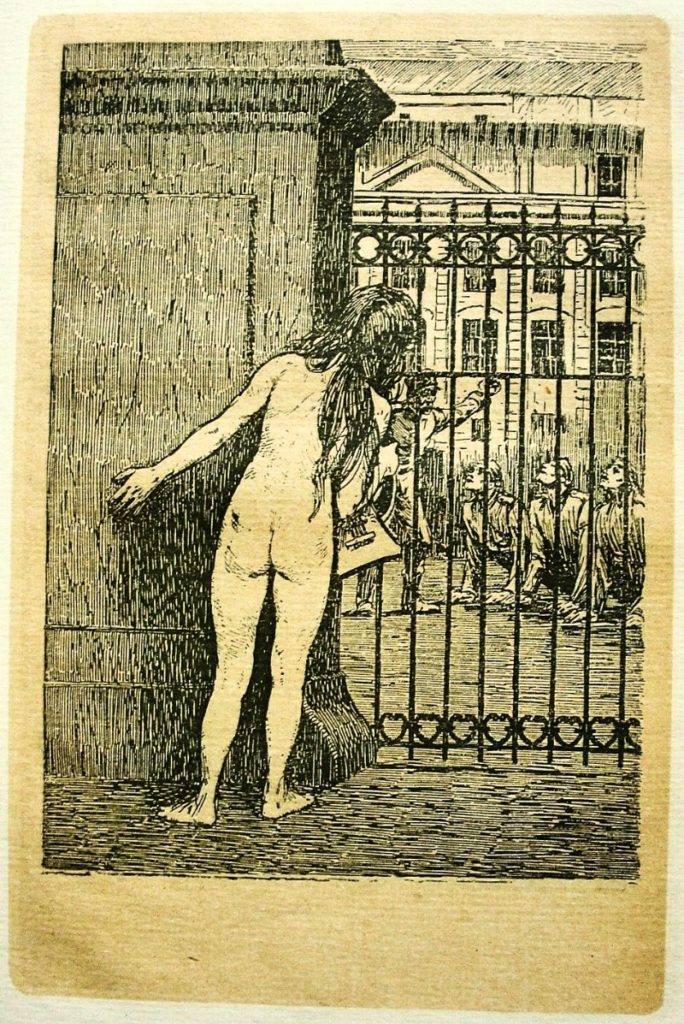

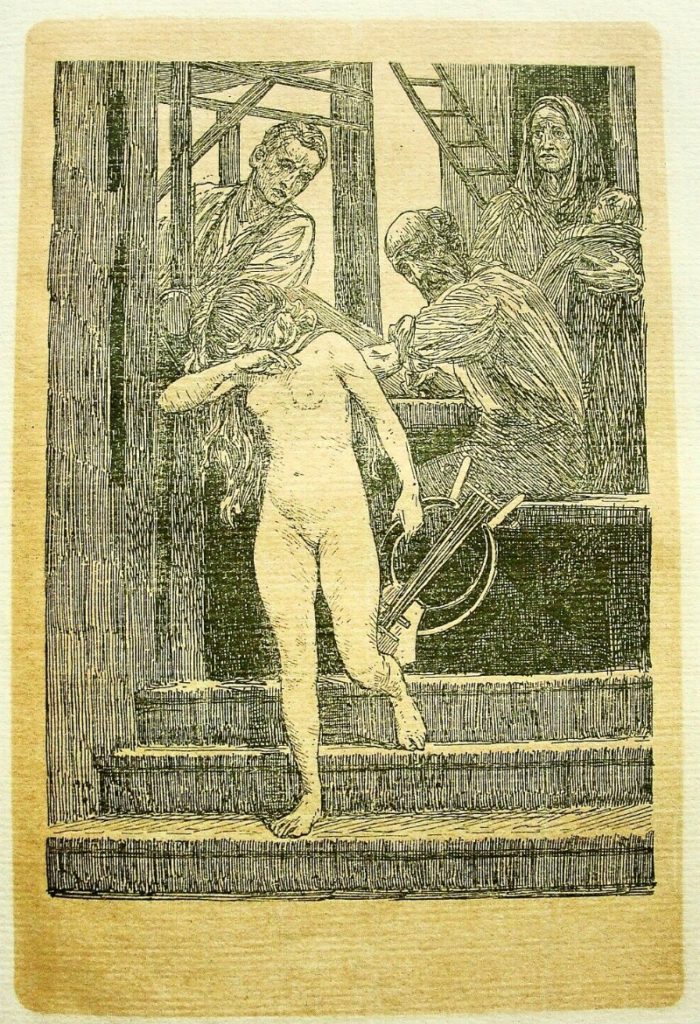

We have a special treat for you today, a very rare peek into a satirical Czech Symbolist publication illustrated by Emil Holárek about an innocent little nymphet, who wears herself out between various institutions of state and society and the wickedness of their protagonists, finally ending up as a supposed culprit on the scaffold. In this 1906 book, reproductions of Holárek’s drawings were skillfully arranged by the Prague based printmaker Antonín Vítek by contrasting them with a ochre surface and ornamental frames and then elegantly printing them on cream machine-mould paper.

The drawings are from the story Pohádka o nadšení -Satirický žert (1906), written by Jaroslav Kvapil and illustrated by Emil Holárek. But first a bit about the artist so you’ll understand why he was the perfect candidate for illustrating this work.

Emil Holárek was born on January 26, 1867. He attended school in Louny, a town in the Ústí nad Labem Region of the Czech Republic which is situated on the River Ohře. This is where, in 1881, three creative Czech personalities met in school

- 1) Kamil Hilbert, the future Czech architect, who would focus mainly on reconstruction of religious buildings, his the most important work being the completion of St Vitus Cathedral,

- 2) Eduard Tregler, who would become a virtuoso and composer of organ church music, as well as a professor and,

- 3) Emil Holárek, who would become a Czech academic painter, graphic artist and draftsman.

He continued his studies at the Prague Academy of Painting and he received a scholarship from the City of Louny, (City Savings Bank). From 1882, he studied at the Prague Academy under prof. Maximilian Pirner and then went to Munich for six years. In 1889, he returned to Prague and continued his studies with prof. František Sequens. He traveled to Rome and was influenced by the German artist and symbolist, Max Klinger.

Josef Behounek, head of the school at that time, recalled, “Holárek … was a contemplative boy, more observant than talkative. This facet of his character escalated with age. In a third grade math class I taught, I discovered he was working on much more than math lessons. Under his bench I discovered a miniature painting studio which I promptly confiscated. As I looked through the sketchbook I viewed masterfully drawn line drawings, representing more significant objects from Louny and its surroundings at that time. It appeared that he sketched on sitge and according to reality, and then completed and filled in more intricate details where possible. Because I was so drawn into his work, I did not notice until much later how he was watching me curiously, assessing how I was looking at his drawings with such interest. I suppose that my interest showed him that it was time to make the first steps. The same day, we discussed his attending the Art Academy where his natural talent and innate abilities could unfold, but his family did not have the funds to support him for years while he was studying. Funds soon appeared in the form of a scholarship and his desire for painting art was fulfilled.

He became a student at the Prague Academy and continued his studies with Professor František Sequenes but perhaps his greatest influence came from his spiritual teacher, Professor Max Pirner. He tried to empathize with the talents of his pupils, and did not suffocate their flight of dogmas. His aim was to develop their talents and spirit interpretations on literature, poetry and philosophy and we can clearly see this influence in many of Holárek’s paintings.

Holárek undoubtedly belongs to the talented generation of masters who created Czech drawings and small graphics at the turn of the century such as Jan Preisler, Viktor Preissig, František Bílek and others. Alongside Max Švabinský and symbolist poet Karel Hlaváček, his work was featured in the journal Moderní revue (Modern review).

He carefully cultivated his drawing, and was influenced in Germany by the works of Max Klinger. While some others were focused on the more beautiful aspects of Art Nouveau and the modern art in the early 20th century, most of Holárek’s work seemed to denounce social conditions.

Some of his work shows a more pessimistic and sarcastic opinion of life. To the point of exhaustion, he devoted himself to criticizing social and political conditions. Undoubtedly, Holárek’s greatest legacy in Czech art are his drawing cycles focusing on their social, anti-clerical and anti-war content.

Many originals of such drawings were exhibited in the Rudolfinum, where their introduction at this time found contrast to what they normally displayed. He found himself fighting almost militantly against the audience and criticism, especially with the changes happening in art.

Anyone who knows a little about the history of art is familiar with the history of impressionism, from which the critical romanceers crazed a revolution of a few who, by chance, came together and fought together for their honesty. At this time, they broke old academic theories and had enough power to – create new ones. From the struggle for artistic independence.

All this development was told by the exhibition in a striking line and – although it did not bring us closer to individuals – it was able to capture the rhythm of the current and its atmosphere and therefore it will always be referred to as one of the most memorable had in Prague.

Emil Holárek bitterly blamed the Rudolfinum for this disregard of his work, there was even news of an intentional boycott – for the exhibition itself was not the most favorable with the many complaints and rebukes. But such was the art world at that time…

Holárek painted in cycles similar to fellow painter Maximilian Pirner and his allegories. Throughout his life, he would return to his painting to repaint, expand, change techniques and try time and time again to improve upon his work. His first published work was in 1895 and it caused a stir.

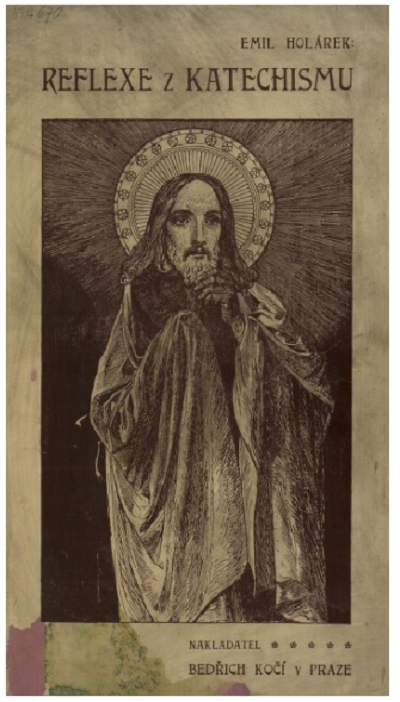

Reflexe z katechismu (Reflection of Catechism) attracted immediate interest in the artist and suddenly Emil Holárek became popular, famous.

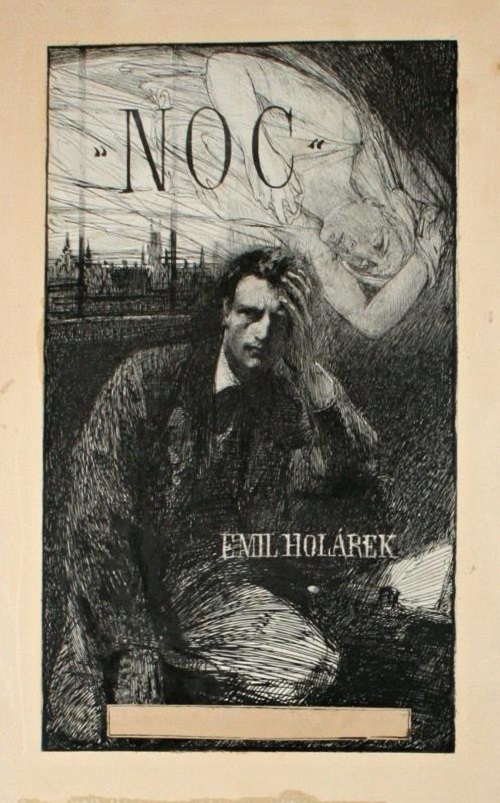

In 1901, he published a series of drawings entitled Noc (Night), which has a deep social undertone. In the series, he confronts the world with the contrasts of the life of the rich and of the poor. Clearly, he doesn’t hide whose side he sympathizes with.

In the same year, he produced another series of drawings based on poems by Jaroslav Vrchlický entitled Cyklus Sen (Cyklus Dream).

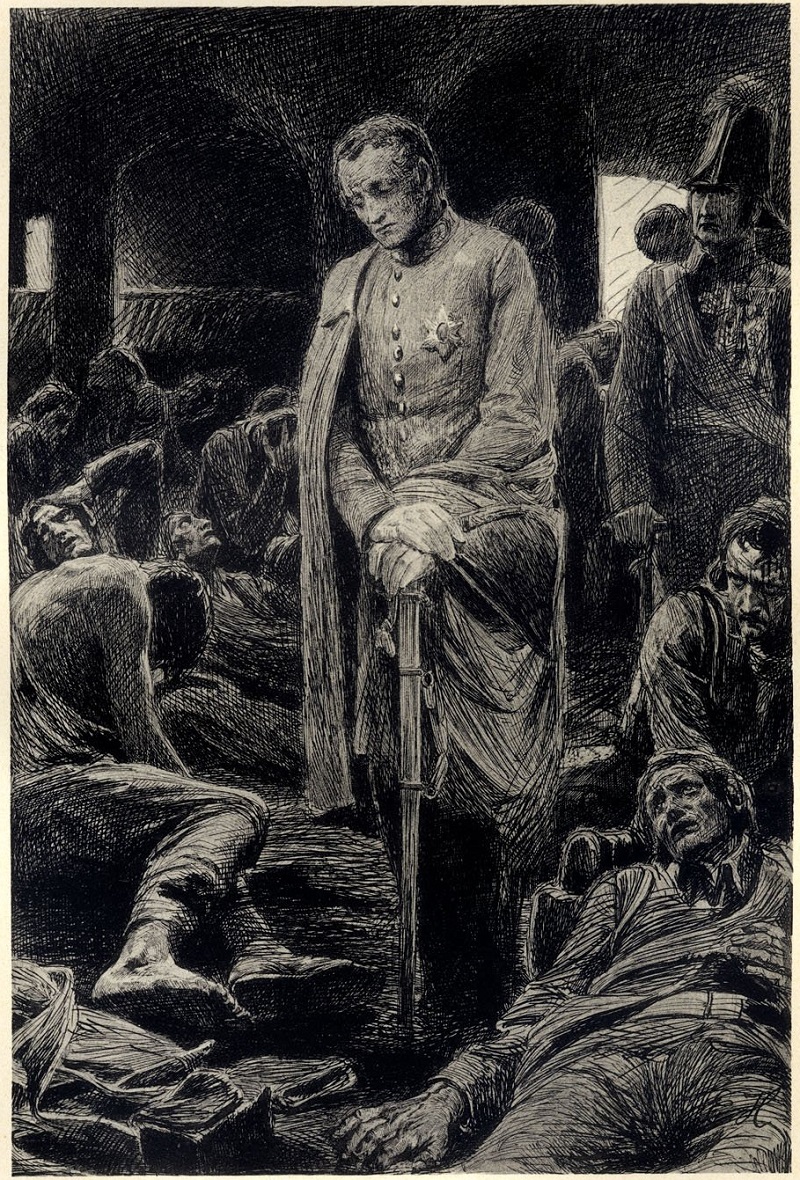

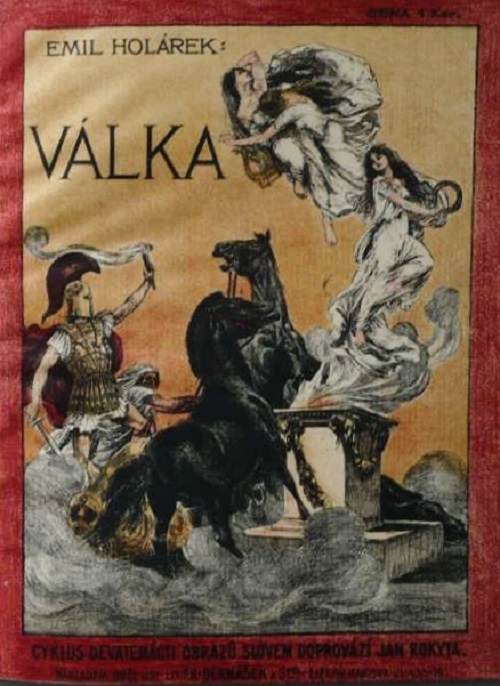

In 1906, he published a series of drawings entitled Válka (War), which reflected the crushing defeat of the Russian Empire in the Russo-Japanese War of 1905. In this work, Holárek’s exasperated soul and feelings about the massacre are evident.

Holárek’s unique style is marked by a somber pessimism. He seems to have embodied a sense of sarcastic moralism in most of his series, reflecting on a deep tragic and romantic conception.

Below is a pastel of a young woman, unnamed and unknown that Emil Holárek drew. Was it a gift he was commissioned to paint? Was it someone he knew? A long lost love?

Items like these show up decades later at auction houses and other such markets and I always wonder, how many times did it change hands? Who was the original owner? What did it mean to them?

Who was this mysterious young woman in Holárek’s artistic repertoire? Did he have a daughter?

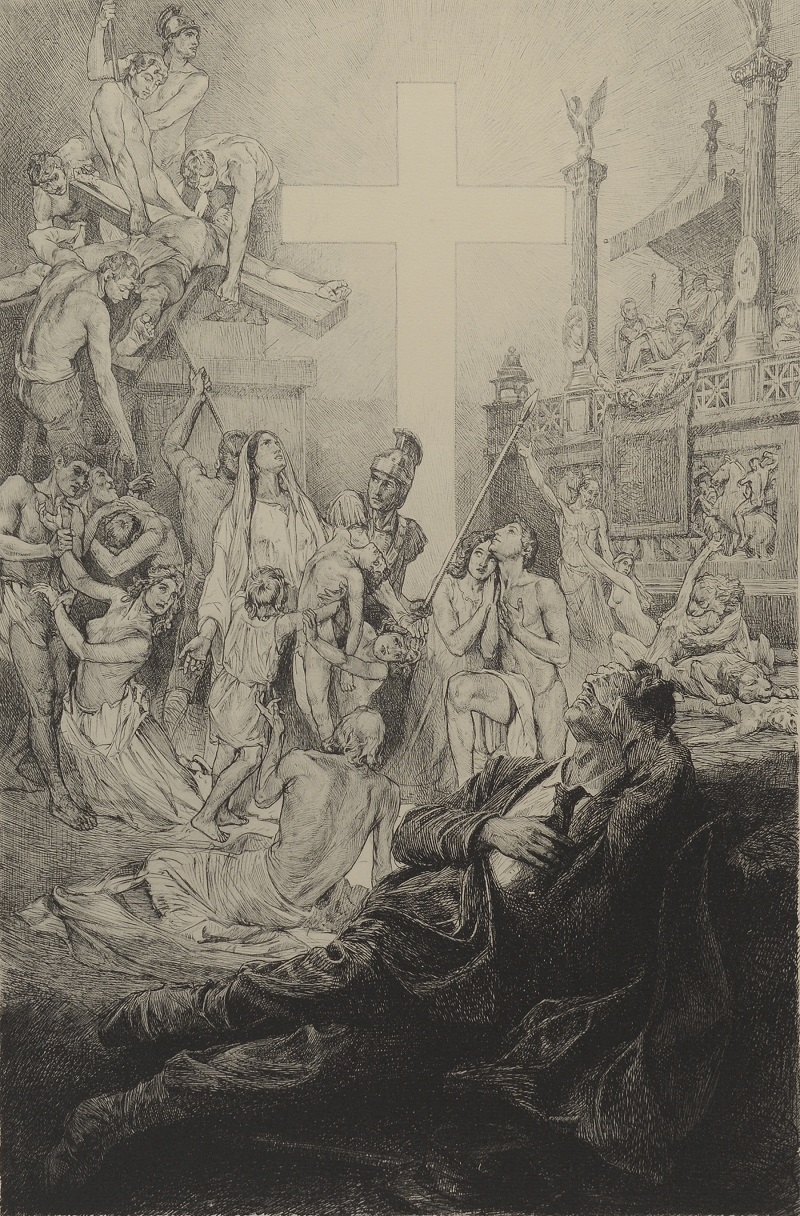

In 1906, he also illustrated Pohádka o nadšení / Satirický žert (The Fairy Tale of Innocence / Satire), the drawings we are viewing here today. I see energetic and hopeful youth and innocence, seemingly unwelcome, turned away… and I wonder how connected to that work Holárek felt. You’ll understand why after the images when you read about the last chapter of this artist’s life.

The images almost parallel the artists inner life. Or at least that is what I imagine when I look at them while focusing on his life story. Seemingly filled with interest to be there, she is turned away or not seen in the way she wishes to be seen. Could this be a representation of how the artist was feeling?

The last chapter of Emil Holárek’s is a very sad one….

In 1916, Emil Holárek – at almost fifty years of age – joined military service in Chomutov and marched into the battles of World War I.

One would expect that he felt his influence coming through his work and that he would have been fulfilled by his political drawings which reached the world, but this was not true. Except for his connection to Max Klinger whom he met when studying in Munich he never allied with any school, nor did he have any followers. He felt alone, the world was at war and he could no longer sit by and watch. He was compelled to actually “do something” and shows he was feeling that the strength and power of his work was not really making any difference. Entering as a cadet and soon reaching the rank of ck lieutenant, most of his friends turned away from him, calling him a renegade and most likely just thinking he was crazy to go off at his age and with the work he was creating. For him, quite possibly, drawing was not enough.

During his time in the Austro-Hungarian army he was awarded several medals, including receiving the Gold Cross of Merit, but this did not make up for the loss of almost all his friends (and that he probably never really believed in his own talent). He returned from the war with undermined health and deeper spiritual wounds which subsequently overcame him completely. He died on February 26, 1919 in Podolí sanatorium, feeling very broken and alone.

His remains were transported to his native Louny where a funeral was held with the participation of nearly all of the residents of the city who celebrated his art and his heroism in the war, but this all came a bit too late. He is buried in the New Cemetary next to his friend, doctor E. Purkyně.

At least the people of Louny gave one last tribute to this incredible artist and man. Do think of him and his work when you travel to Louny and you walk through Holárkovy sady, named after him.

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Thank you in advance!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.