Today’s information is as shocking as the headline, Alice Masaryk Arrested & Held in Prison. Below we are sharing a reprint of an article written in 1974, with quotes and images added by us. Original source information at the end. It’s an important history lesson and it shares something many folks don’t even know – about the time Alice Masaryk was was interrogated for two weeks in Prague, and then moved to a prison in Vienna.

Historians are generally agreed that during the first two years of World War I American feeling against Germany was far stronger and more intense than against Austria-Hungary. While relations between the Germanic and American peoples had not been truly friendly since the 1880s, attitudes in the United States toward Austria-Hungary were much less antagonistic. Historically there had been little direct contact between the latter two countries. It scarcely seemed necessary to Americans. The area was not only remote geographically but also remote from the national interest. As a result, there appeared to be no deep-rooted bitterness or resentment in the historic relationship between the two nations. Indeed, in the period immediately preceding the war, relations between Austria-Hungary and the United States had consisted largely of diplomatic formalities even though before the war, Austria-Hungary, next to Italy, had furnished the largest European immigration to the United States.(1) Americans for the most part were unaware that Austria-Hungary was a multinational empire composed of many diverse ethnic groups. Few Americans knew of the vast numbers of immigrants who had come from Austria-Hungary from the areas of Slovakia and Bohemia. By the outbreak of World War I there were approximately a million and a half Czechs and Slovaks of the first and second generations in the United States. Their largest center was in Chicago, which was the second largest Czech city in the world, next only to Prague

Not only were few Americans aware of these people as separate ethnic groups within the Austro-Hungarian Empire; they knew even less of their national aspirations. Bohemian history was virtually unknown among the general public in the United States. If Americans thought of Bohemia at all, it was apt to be as the land of the gypsies.(2)

People argued that when even women were imprisoned the movement must be serious.

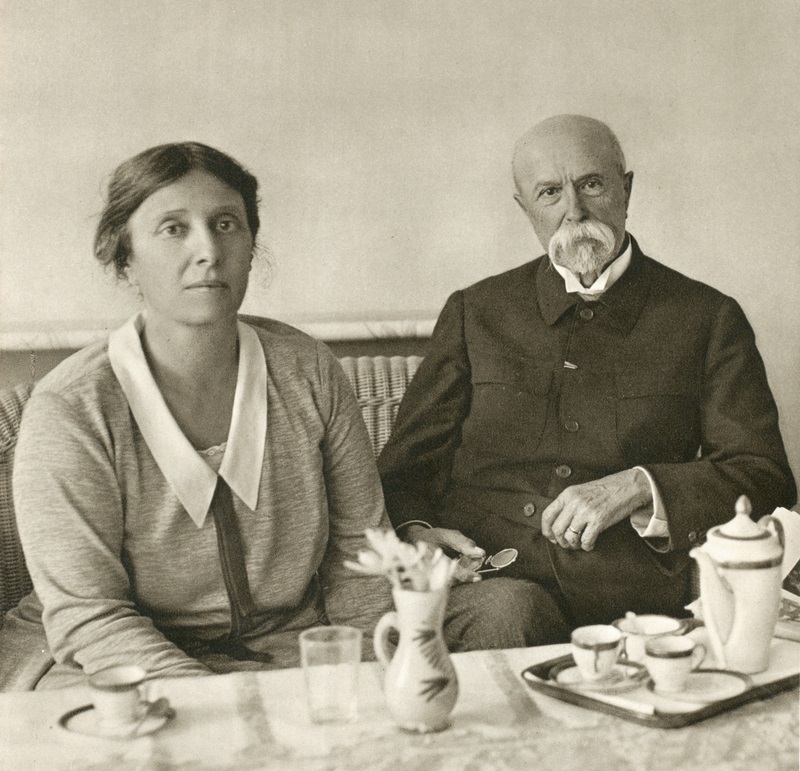

T.G.Masaryk

During the early years of World War I, the two events which aroused the strongest public opposition to the Austro-Hungarian regime and at the same time engendered the greatest sympathy for the Bohemian liberation movement were the Dumba revelations and the Alice Masaryk affair. In the first case, the American government asked for the recall of Dr. Constantin Dumba, the Austrian ambassador in the United States, when documents captured by the British revealed his efforts to incite strikes in American munitions factories. Though many American history textbooks discuss the Dumba affair, almost no mention is made of the Alice Masaryk case, in which the older daughter of Professor Thomas G. Masaryk, eminent Bohemian scholar and political leader, was imprisoned on charges of high treason in Austria-Hungary. The significance of this event in arousing antagonism to Austria-Hungary and creating support for the Bohemian liberation movement has been almost totally overlooked by historians to date. Yet Professor Masaryk himself, founder of the Czechoslovak Republic, clearly pointed out in his memoirs what a great service was rendered its cause, particularly in England and America, by the arrest and imprisonment of his daughter Alice. As he put it, “People argued that when even women were imprisoned the movement must be serious.”(3)

Ultimately, the widespread publicity given the Alice Masaryk case was the result of three separate factors: first, the efforts of Charles R. Crane, wealthy philanthropist and businessman; second, the support of selected leaders of the women’s movement in Chicago, New York, Boston, and Washington, D.C.; and, finally, the work of the Bohemian National Alliance. By 1916 Crane was the most important friend the Czechs had in the United States. Head of the Crane Plumbing and Manufacturing Company, he had acquired an early interest in Russian affairs and had endowed a School of Slavonic Studies at the University of Chicago. He had become a Czechophile gradually, but at a time when this was so unusual as to make him an eccentric. In 1896, when Crane was planning a trip to Russia and East Central Europe, he had been urged by his intimate friend, William R. Harper, president of the University of Chicago, to contact Professor Masaryk, who was rapidly becoming the significant leader of certain Slav groups opposed to Pan-Slavism. Thus, Crane had gone to Prague mainly in the hope of meeting the well-known Czech scholar.

During the visit the two men spoke at length of their mutual interest in Slavic affairs. So rare was it for an American to be sympathetic and concerned about the welfare of the Slav peoples, that both Masaryk and his wife believed that Crane, whom they typified as a mild-mannered idealist, must be a missionary out on a fund-raising tour. Apparently Professor Masaryk did not enjoy his tea that day, for he was busy making a close calculation of his finances to determine how much he could spare to promote the good works of his misty-eyed visitor. The Masaryks were later greatly surprised and amused when they learned of Crane’s business interests. Crane’s visit to Prague initiated a relationship which grew closer over the years. Indeed Crane’s son, John, recalled that in many ways his father became Masaryk’s closest friend.(4) In 1902 Crane traveled to Prague to invite Professor Masaryk to lecture at the School of Slavonic Studies at the University of Chicago. This brought Masaryk to the United States and acquainted him with Slavic people throughout the nation.(5)Thus it was not surprising that Crane was the first American to whom Masaryk turned for help in supporting the Czech cause at the outbreak of the war.(6)

Crane was a useful friend to have. In due course he became increasingly close to President Wilson and various members of his cabinet as well as Colonel Edward M. House, and thereby in a position to exercise influence in determining Wilson’s attitude toward Masaryk and Czech nationalistic aspirations.(7) Crane had great admiration for Wilson and played an active role in his presidential campaign, becoming the largest single financial contributor. Like many of Wilson’s admirers, he saw the president as the prophet for whom the world had been waiting.(8) Wilson also had a high regard for Crane, and twice sought to appoint him as an ambassador, first to Russia and later to China.(9) During the winter following the election, the relationship between the two became very close. Crane not only corresponded with the president regularly, he was also a frequent visitor at the White House. Indeed, Crane was the first person whom the president saw when he took office officially in the White House on the initial day of his presidency.(10)

After the beginning of 1915, Crane’s location and connections made it possible for him to be even more supportive of the Czech cause. In the first part of the year he moved from Chicago to Woods Hole, Massachusetts. From here he was better able to visit with Colonel House and to entertain members of Wilson’s cabinet and other persons of note who might be in Washington. Later, during the summer, through the good offices of friends in high places, Crane’s son Richard was appointed secretary to the new secretary of state, Robert Lansing. This was a position in which he could be influential within the State Department in presenting the Bohemian case and at the same time acting as a go-between. The elder Crane was deeply gratified over his son’s appointment.(11) It was young Crane’s interest in Bohemian affairs that ultimately led to his appointment as first minister to Czechoslovakia.

The second factor involved in the widespread publicity given the Alice Masaryk affair was the interest and concern of dedicated leaders of the women’s movement. Particularly those associated with the University of Chicago’s Settlement House and Hull House in Chicago and the Henry Street Settlement in New York. City had become well acquainted with the Czech and Slovak emigrants who resided in their midst. They knew of their customs, traditions, history, and hopes probably better than anyone else in the United States at that time. Many of these women had become closely associated with Alice Masaryk on her first visit to the United States. Mary McDowell, head of the University of Chicago Settlement House, had befriended many Czechs and Slovaks whom she had seen grow up in Chicago. She had encouraged Professor Emily G. Balch of Wellesley, at one time with the Chicago Settlement House, in her sensitive writings about Czech immigrants.(12) She had also inspired and supported other academicians to deeper research and writing about the Czechs.(13) Her distinctive services on behalf of the Czechs were later to win for her the Order of the White Lion given by the Czechoslovak Republic.

The third agency concerned by the arrest was the Bohemian National Alliance. This organization, founded in the United States in the late summer of 1914, had been formed for the specific purpose of informing the public both in Europe and in America of the just demands of the Czech and Slovak peoples for independence in order to prepare the ground for achieving it. The movement was headquartered in Chicago under the leadership of Dr. J. L. Fisher.(14) In New York the movement was directed by Emmanuel Voska, who had been visiting in Prague at the outbreak of the war. There he had met Masaryk, who in turn had persuaded him to serve as a courier to his friends in London and America. Voska was an ardent Czech nationalist who had been expelled as a youth from Bohemia by the Austro-Hungarian government on charges of socialist activities. He had come to the United States in 1894 and made a comfortable fortune in business enterprises in New York and Kansas City. He also had a part interest in a Czech-language newspaper. Married to an emigrant Czech girl, he had fathered four daughters and two sons and become prominent in the Bohemian colonies and president of the American “Sokols,” patriotic gymnastic societies, an idea transplanted from Bohemia to the United States by Czech immigrants.

When Masaryk had visited the United States in 1910 and 1912, Voska had arranged a series of lectures for him before branches of the Sokol. Voska approved of Masaryk’s wise moderation and careful organization in preparing the foundation for Czech and Slovak liberation. He had become Masaryk’s disciple and dedicated follower.(15) Later, it was Voska who arranged with the British government and the Russian ambassador to Britain for Czechs who deserted across the eastern battle lines to Russia to receive different treatment from other Austrian prisoners of war.(16) When Professor Masaryk went abroad on his third trip, he informed Voska of the arrests and executions that were occurring in Austria-Hungary, and voiced his doubts whether he would be able to go back.(17)

The publication of such activities on the part of German and Austrian officials had an immense influence on public opinion.

Voska’s dedication to the Czech cause was tireless. Working with the Bohemian National Alliance, he had been instrumental in 1915 in revealing to the American government the sabotaging activities of Captain Franz von Papen and Captain Karl Boy-Ed, which resulted in the expulsion of both of these German attaches as well as the Austrian ambassador, Dumba.(18)

The publication of such activities on the part of German and Austrian officials had an immense influence on public opinion. Indeed, one British historian has suggested that they may well have been even more vital in alienating American opinion from the Austro-Hungarians and the Germans than the catastrophe of the Lusitania itself.(19) Crane had been deeply impressed with Voska’s efforts, and had great admiration for this “small Bohemian merchant, who does not at all look the man who had undone many of Germany’s most carefully conceived and executed plots.” Crane was aware of Voska’s contacts with Masaryk.(20) Actually, it was Voska who in late 1914 had returned from Bohemia to the United States, via London, with the first news of the preparations that were being made by Masaryk and his friends for the ultimate liberation of the Czechs and Slovaks. Thus the initial task of the Bohemian National Alliance was to convince the Czechs in America that political action was now necessary and opportune.(21)

Once Masaryk had established the Czechoslovak National Council in Paris as the official instrument to direct the national liberation movement, he became deeply aware of the need for financial support. Naturally he turned not only to the Bohemian communities in the United States, which were a comparatively wealthy group, but he also sought the financial help of his friend and benefactor, Crane. Masaryk had feared to write to him directly from Bohemia because of the possibility of police interference, so he had been forced to seek his aid through an intermediary. However, once he had arrived in Geneva and given up the hope of returning to Prague, he decided to inform his American friend and seek his support. He wrote the elder Crane of his plan “to organize Czech journalistic and political representations abroad and to keep in touch with the politicians of the Triple Entente.”

Please help us, in obtaining a high and noble end.

T.G. Masaryk

He made clear his objectives in seeking the independence and freedom of the Bohemian nation. He desperately needed the financial help of his friends abroad, not only to relieve the men and families “who had become victims of military absolutism, reigning all over Austria and particularly in Bohemia,” but also to help organize the political movement abroad. He wrote of his secret sources of information, his plans to organize the Sokols for emergency use, and his conviction that once the Russians advanced to the Bohemian provinces the time would be right for securing independence at home. He reported his efforts both to organize Bohemian legions in Russia and in France and to raise funds to organize and support the political movement. He urged Crane not only to contribute personally but to elicit the support of his friends for the Bohemian cause. “Please help us,” Masaryk wrote, “in obtaining a high and noble end.”(22)

Crane was clearly sympathetic. Not only did he send money, but apparently he informed some of the Czechs in the United States that if they kept within reasonable limits, he saw no reason for the administration to put obstacles in the way of their agitation for racial independence.(23)

During the first few years of World War I the Bohemian National Alliance sought to publicize its program in the usual manner, by writing articles and statements for the newspapers, presenting memoranda to the president through various committees of Congress, and using every opportunity to convert prominent Americans to the Czech cause. In presenting its case to the public, the Alliance stressed the historical right of the Bohemians to independence, the repression of the Austro-Hungarian regime, the arrest and imprisonment of Czech patriots sympathetic to the Allied cause, the mutinies of Czech soldiers and their desertion to the Russians, Serbs, and later the Italians, and finally the loyalty of Czechs and Slovaks to America’s neutrality policy.(24)Crane also spoke for the Czech cause.(25) When the Alice Masaryk affair occurred, it provided a great opportunity to publicize the Czech liberation movement. The American public naturally responded in sympathy to the plight of this distinguished young woman, daughter of the well-known Czech patriot.

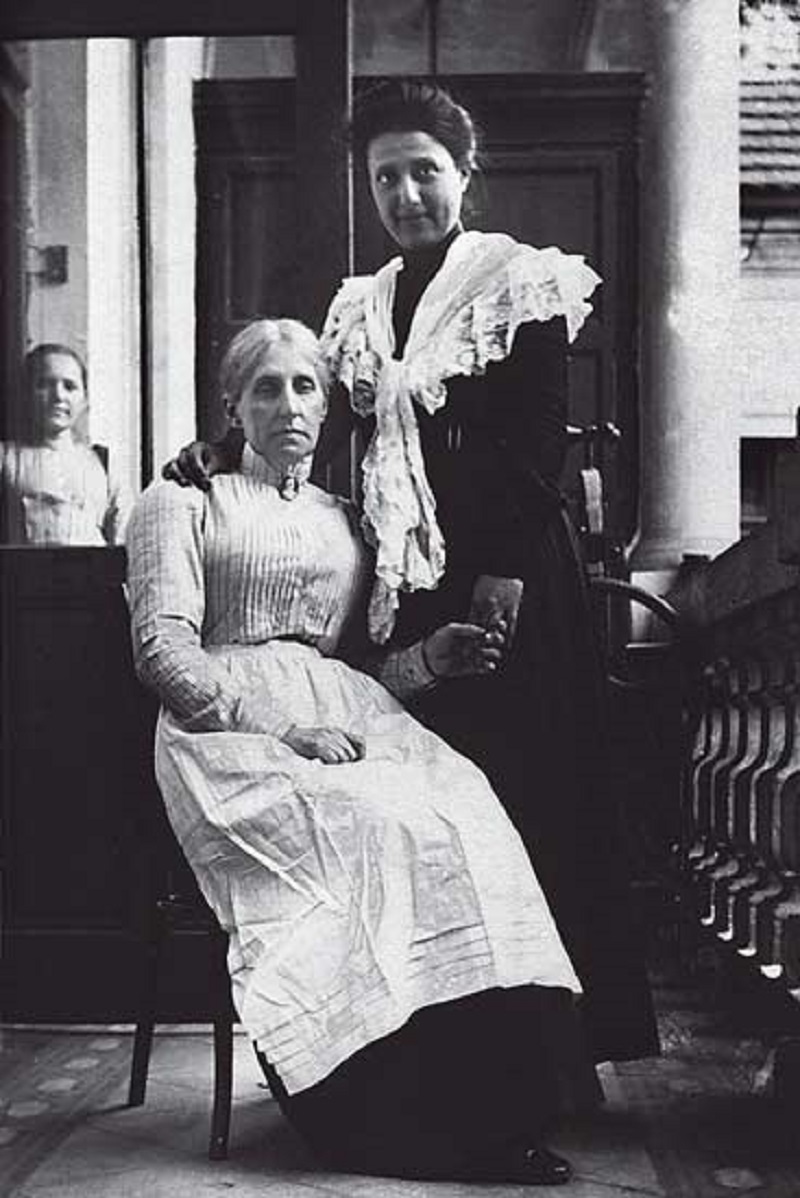

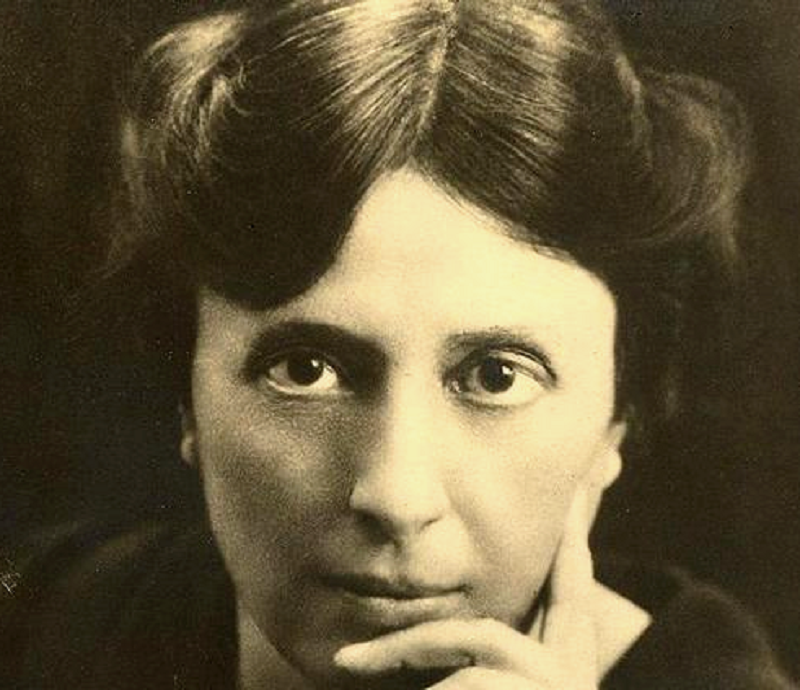

In 1905, when Professor Masaryk arrived in Chicago, he was accompanied by his daughter, Alice. Miss Masaryk was a talented, attractive, and well-educated young woman who had graduated from the University of Prague and taken the degree of Doctor of Philosophy at Berlin University.

She was writing a history of Bohemia and desired to know more about Bohemians in America. She lived for a year at the University of Chicago Settlement House and also spent some time at the Henry Street Settlement in New York City. During her stay she made many friends. In Chicago she organized a clean-up club, and worked in cleaning up the alleys in the back of the Stock Yards. She also organized the Young Bohemian Women, and spoke to many organizations of Bohemian women in Chicago. Among those whom she impressed with her talents and abilities were Jane Addams of Hull House, Miss McDowell, president of the Chicago Woman’s Club, Mrs. Charles R. Crane, Dr. Julia Lathrop, chief of the Children’s Bureau of the United States Department of Labor, Miss Lillian D. Wald, head of the Henry Street Settlement House in New York, and many other prominent organization women.(26)

She was being prosecuted by the military authorities

Early in 1915, Miss McDowell received a letter from Miss Masaryk which indicated that she must be in some kind of grave difficulty. The letter was mysteriously worded but ended with an appeal for $500. Miss McDowell sent the letter on to Mr. Crane, to whom Miss Masaryk had also appealed for help.(27) By November 1915, when the State Department was engaged in negotiations with Austria-Hungary over the sinking of the Ancona, and the public had been thoroughly aroused over the Dumba revelations, the news was confirmed of Miss Masaryk’s imprisonment. She had been arrested on October 28, 1915, in Prague, and then confined from November 7 in the Landesgerichtliches Gefangenhaus, cell no. 207, in Vienna. Proceedings had already been instituted for high treason against her father by the Austrian authorities. The American ambassador in Vienna had difficulty in obtaining further information, as she was being prosecuted by the military authorities.(28) Masaryk, now in England, immediately wrote to Crane for help.(29) He surmised that his daughter had been imprisoned for “putting aside” certain of his books and manuscripts, although he had asked her to do this soon after he left Prague at a time when such communication was not a political crime. He was concerned that perhaps his wife, an American, the former Miss Charlotte Garrigue, would also be imprisoned. In that event, he anticipated the intervention of the American Embassy. As the days wore on, Masaryk became even more deeply concerned, and on November 29 he again cabled Crane asking him to “intervene as asked last letter.”(30)

The elder Crane immediately set aside personal plans and threw himself into the effort to aid Alice Masaryk. It was his desire to “do anything in the world . . . for her.” His purpose was to publicize the “Alice Masaryk Affair” to the point where it would create as much public disapproval as the “Edith Cavell Case.” He hoped to engender sympathy not only for Miss Masaryk herself, but also for the cause of Bohemian independence. He contacted American and Bohemian newspapers and news agencies, and also induced the New York Times to publicize the case. He himself made the outline of articles which he sent on to newspapers. He enlisted the support of both Miss McDowell of Chicago and Miss Lillian Wald of New York. He also secured the help of Robert Young (nephew of Lord Bryce), who was in the United States studying Slavic peoples and especially the Czechs, and who was sympathetic and familiar with Masaryk’s entire story. Crane next sought the assistance of the Christian Science Monitor, which had earlier been deeply interested in his comments and contributions on the Russian situation. He had already received their support of the Bohemian cause. To this end, they had published several important articles and an editorial based on interviews with Professor Masaryk himself. Indeed, they appear to have published the first interview by an American correspondent with Professor Masaryk along with an illustration of the professor drawn especially for the Monitor prior to the United States entry into the war. Masaryk had then expounded at length on the position of the Slavs within the Austro-Hungarian Empire, of their close relationship to Russia, and their ultimate desires for independence, which alone could rid Europe of the major problem responsible for the war’s origin. Crane also solicited the help of his son Richard through the State Department. He even went so far as to send a personal cable to the Austrian premier himself, whom he knew, warning him in a very friendly way of the “dynamite” in the matter.(31)

The news media speculated that the arrest of Alice was a move on the part of the Austrians to silence her father who was espousing the cause of the Allies in England. Members of the various Bohemian organizations under the leadership of Congressman A. J. Sabath brought the matter to the attention of the State Department in an effort to secure the government’s intervention.(32) Both Voska and Vojta Benes, who was a brother of Edvard Benes, secretary of the Czechoslovak National Council in Paris and organizer of the Bohemian National Alliance, publicized Miss Masaryk’s case and sought to use it to call the attention of the American public to the discontent that existed in Austria-Hungary and the arrests which had recently been made of prominent Czechs. Vojta Benes even expressed the fear that the Austrians might have executed Miss Masaryk. The Reverend Vincent Pisek of the Jan Huss Neighborhood House in New York City and his assistant K. D. Miller, later to play an important role with the Czech legions in Russia, reported on her impeccable character and her wide acceptance and popularity among Bohemians in New York City. Although the Bohemian papers were featuring the case of Miss Masaryk, they admitted that they were powerless to help her even if she was still alive.(33) The editor of Bohemian Women’s Weekly feared that Alice had been imprisoned because of her father’s wellknown pro-Allied tendencies, since she herself was not involved in political activities.

The Bohemian cause also had a devoted friend in Representative Adolph J. Sabath, a Bohemian-born Chicago lawyer. Sabath had earlier been deeply concerned over the case of four prominent Bohemian leaders who had been condemned to death in Austria on charges of treason. He had even interceded with President Wilson on their behalf.(34) President Wilson, in turn, had inquired of his secretary of state whether anything might be done for “these unfortunate men.” Although sympathetic to their plight, Lansing made clear that since they were Austrian subjects, he was powerless to aid them. The United States was “unable to intervene even on the grounds of humanity” in the treatment which foreign subjects received in their own country as a result of judicial proceedings. He added, “We would not brook such interference in our own affairs, and to make a suggestion to the Austrian government in the case of these four Bohemians would, I think, not only establish an embarrassing precedent for us but would probably meet with rebuff by that government, and might even have an effect contrary to that which the suggestion was intended to produce.”(35) Despite Congressman Sabath’s lack of success in regard to this similar case, as soon as he learned of Miss Masaryk’s imprisonment he wired immediately to Vienna to withhold any action if such was contemplated until they heard from the United States.(36) He also brought the matter forcefully to the attention of the State Department “in the name of the Bohemian people in Chicago.”(37)

Chicago civic and social workers were particularly interested in the case because of Miss Masaryk’s former residency in their city and because her mother was an American and a cousin of Mrs. Alice Putnam, a leader in Chicago kindergarten work. Miss Jane Addams, Miss Mary McDowell, Mrs. Charles R. Crane, Dr. Julia Lathrop, Miss Elizabeth Jones, and other prominent professional women appealed to the State Department to do what it could to secure the release or at least the safety of Miss Masaryk.(38) They were much alarmed when they received word from the Bohemian National Alliance that Miss Masaryk had already been executed.(39) Chicago members of the National Bohemian Alliance aided by Jane Addams and other Hull House workers urged a State Department inquiry into the reported execution. The State Department, however, had no confirmation of the report.(40) Dr. Lathrop, also a former resident of Hull House, requested the State Department to cable the American consul at Prague inquiring about the whereabouts and well-being of Miss Masaryk.(41) In response to this telegram the State Department learned from Ambassador Frederick C. Penfield at Vienna that she had been imprisoned at the capital, presumably on a charge of high treason. Penfield was led to believe that “owing to the mass of evidence, the preliminary investigation [would] take some time,” so that the trial could not be expected in the near future. The ambassador added that further news of Miss Masaryk could not be obtained there.(42)

The newspapers were eloquent in describing Miss Masaryk’s case: Her “personality was impressive because of her sincerity and genuine simplicity. She was distinguished looking and beautiful when animated by an idea or when speaking in public. She was magnetic and forceful. All who know this gentle, sympathetic, and simply democratic young woman will believe her innocent of the charge of treason. She had a constructive mind and was no anarchist in word or deed. To take the life of, or, to imprison one so young and so noble will be an atrocity that cannot be forgotten by American women.”(43)

American women were urged not to “keep still and allow this cruel act of injustice to a gentle, young woman, whose only deed that the Austrian government can question is that she agreed with her heroic father, who cannot take up arms against Serbia whose problems he understands so perfectly.” They were exhorted individually and collectively to send at once through the State Department a plea for leniency toward her.(44)

Miss McDowell, who had roomed with Alice Masaryk during her stay at the Chicago Settlement House, was particularly active in her behalf. Professor Masaryk had written several letters and had also cabled to her of his daughter’s innocence, indicating that he had been extremely careful not to involve her. Olga Masaryk, Alice’s sister, had also written at length, pleading her sister’s innocence. She wrote that her father “fearing for her safety told her nothing political.” Reassured by this information, Miss McDowell spared no effort. Not only did she speak and write in Chicago, she also traveled to other cities and especially to Cleveland to encourage the large settlement of Bohemians there to take action on her friend’s behalf. However, her major effort was directed to arousing the women of the country to press for State Department action.(45)Her appeal, urging all American social workers to petition Secretary Lansing to aid Miss Masaryk or at least find out whether she had been executed, fell on fertile soil. She herself wrote special pieces for the Chicago Daily Tribune and the Survey.(46) The largest Czech-American newspaper in the country reported that forty thousand letters and telegrams were sent to Vienna as a result of Miss McDowell’s campaign.(47)

On April 25 thirty representatives of the clubs making up the Bohemian Alliance of Chicago held a meeting to plan a public appeal for the life of Alice Masaryk. The women represented some forty thousand Bohemians. In other cities throughout the country similar action was taken.

Mary McDowell, who had just returned from New York in the interests of Miss Masaryk, spoke. She was followed by a spokesman from the Bohemian National Alliance who expanded on the wrongs suffered by Bohemia under the rule of Austria-Hungary and of the great services rendered the Bohemian cause by Miss Masaryk’s father. He then read a resolution, drawn up by the Alliance, which was bitter in its criticism of the Austrian government. It read, in part, “In our minds Austria is guilty of this war. In their despotism and tyranny they would not hesitate to put to death this girl—to punish the father through the daughter.”

I would rather have a living heroine than a dead martyr to the cause of Bohemia.

Miss McDowell urged the Bohemians to moderate their criticism, which she believed could only hamper the State Department and thus fail in its effect. She pushed for the adoption of a resolution she had drafted in cooperation with Jane Addams which included the word “leniency,” although she said, “We would all like to say what we thought about Austria, but just now the question is to save Miss Masaryk. I would rather have a living heroine than a dead martyr to the cause of Bohemia.” She thereby urged that the resolution be in the form of an appeal rather than a protest.

Ultimately a resolution drawn up by Grace Abbott, former resident of Hull House and director of the Immigrant’s Protective League, was accepted which read:

We the undersigned American friends of Alice Masaryk, whose mother was an American citizen, have learned with deep concern of her imprisonment in Austria on a charge of high treason. Knowing as we do her nobility of character, her fine sense of honor, her humanitarian interest, her distinguished scholarship, we urgently request the State Department to use all possible influence with the Austrian government to ensure against any summary military action being taken in her case.(48)

Members of Bohemian organizations also coordinated their efforts to bring the Masaryk case to the attention of the State Department and to procure possible intervention by the government.(49) Petitions, resolutions, telegrams, and letters poured into the State Department from all parts of the country. Among the many organizations sending appeals were the University of Chicago Settlement Woman’s Club, Bohemian Woman’s Medical Club, the Fabian Club of Boston, Chicago Woman’s Club, Women’s Peace Party, Women’s Trade Union League, University of Chicago Faculty, Bohemian National Alliance, and the Immigrant’s Protective League.(50)

Although State Department officials were impressed by these appeals, they found it difficult if not impossible to aid Miss Masaryk, since she was not an American citizen. Richard Crane wrote his father that as in the case of the four arrested Czechs for whom Congressman Sabath had intervened earlier, the Department believed it could not properly take any steps with reference to Miss Masaryk’s detention, because she was a subject of Austria-Hungary. However, this was a matter which might properly be taken up with the Austrian Embassy in Washington, D.C.(51) When Myron T. Herrick, former ambassador to France, wrote to the State Department asking if there was “anything possible” that he could do to aid Miss Masaryk, Frank L. Polk responded, “A number of informal messages have been sent through which may be of some assistance. We have suggested to everyone the advisability of taking up the matter with the Austrian Embassy here and I feel sure that representations from a man like yourself would have the greatest weight.”(52)

Alice Masaryk Already Executed.

On April 27 the Chicago Daily Tribune printed on page one the headline “Alice Masaryk Already Executed, New York Hears.” The news was reported by the Bohemian National Alliance, which claimed to have received the information from a secret source which also noted that other prominent Bohemians had been executed along with her.(53) Denni Hlasatel wrote that there was “no hope that Miss Masaryk escaped with her life.”(54) When questioned on this report, Miss Lillian Wald of the Henry Street Settlement said that while she had not received any news of the fate of the young woman, she was “still hopeful that the Austrian government had not executed her.”(55)

Within the next few days Miss Masaryk’s supporters increased their efforts. Under Miss McDowell’s leadership, a meeting of the Chicago Woman’s Club was called to organize a council to exert pressure on Washington and Vienna for Miss Masaryk’s release. Congressman Sabath called upon Secretary Lansing, who promised to send for immediate reports. Charles Crane, various congressmen, and prominent citizens continued to seek intervention on her behalf. Although powerless to intervene directly in her case, the American government, Denni Hlasatel reported, had “indicated its deep concern and sympathy in her fate.”(56)

In the meantime, the Women’s Peace Party had interested itself in the affair as a result of Miss McDowell’s appeal. On May 9 Mrs. Glendower Evans of the Massachusetts branch of that party reported through Professor Hugo Munsterberg of Harvard University, who was said to have a good deal of influence at the Austrian Embassy, that Miss Masaryk was safe and was being held only for preliminary trial by the Austrians.(57) Several weeks later, Miss McDowell confirmed this report. She added that a “great deal of quiet influence has been going on with the embassies in Vienna and Berlin,”

while prominent Chicago Germans had been working with telegrams and “words of good will.”(58) Several months later the New York Times confirmed that Miss Masaryk was safe, although still imprisoned.(59) Former Ambassador Herrick was also engaged in quiet intercession for Miss Masaryk. He had been conducting his efforts through Count Szecsen, former Austro-Hungarian ambassador in Paris during Herrick’s tenure there, from 1912 to 1914.(60)

Masaryk’s daughter is still a prisoner in Prague with no formal charges preferred against her and no date set for her trial.

Nevertheless, in a special interview with Professor Masaryk a few weeks later, the New York Times reported that his daughter was still a prisoner in Prague with no formal charges preferred against her and no date set for her trial. According to Professor Masaryk, she was guilty of no offense except perhaps sending a few books to her father in Switzerland. He noted that Mrs. Masaryk was safe. Masaryk took the occasion to report that Bohemia was prepared to separate from Austria-Hungary, that they were a Slav race, and thoroughly Slav in sympathy. The professor suggested that this might partly explain the huge numbers of prisoners that the Russian army had captured with such ease. He also pointed out that there were already Bohemian legions fighting for the French and the Russians.(61)

On August 20 Alexander von Nuber, the Austrian consul-general, announced Miss Masaryk’s release.(62) According to the reports in Denni Hlasatel, Austrian officials could find no proof of any subversive activities on her part. The account suggested that the great interest evinced by the American public in Miss Masaryk’s fate, combined with the stream of protests sent to Vienna, may well have influenced the Austrian authorities.(63) The entire affair had clearly served to focus the attention of the American public on the political unrest in Austria-Hungary as well as on the desires of the Bohemian people for independence.(64) Both Charles R. Crane and the Bohemian National Alliance, while deeply sympathetic to the plight of Miss Masaryk, used every opportunity in publicizing her case to present the cause of the Bohemian liberation movement as eloquently and effectively as possible.

Scarcely a news article covering the affair failed to present it against the historic background of Bohemian aspirations for freedom and independence from the repressions of the Habsburg Empire. However, the women’s movement and particularly the Women’s Peace Party were primarily concerned with the cause of human justice and only secondarily interested in Bohemian independence. Indeed, insofar as they supported the peace movement, they were really opposed to the efforts of the Bohemian National Alliance, which sought the prolongation of the war, the eventual involvement of the United States, and an Allied victory, since these objectives offered the greatest hope ultimately for Czechoslovak independence. Nevertheless, these three groups working together in the interests of Miss Masaryk’s freedom were successful in providing, next to the Dumba case, the most effective opportunity for arousing popular antagonism to the Austro-Hungarian regime and promoting interest in the Czechoslovak independence movement in the United States during the first two years of World War I.

- U.S. Department of Commerce, Statistical Abstract of the United States, 1916 (Washington, D.C., 1917), pp. 106-7; New York Times, Jan. 13, 1914.

- Stephen D. Kertesz, ed., The Fate of East Central Europe (Notre Dame, 19S6), p. 21; Henry Adolphus Miller, “The Rebirth of the Nation: The Czechoslovaks,” Survey, Nov. 2, 1918, pp. 117-20; Karl Wittke, We Who Built America (New York, 1939), p. 411. Not until the spring of 1918 did the term “Czech” begin to appear in American newspapers and periodicals. Prior to that time, information regarding the Czechs could only be found by searching under the term “Bohemian.” The Czech national organization was called the Bohemian National Alliance and the national journal, the Bohemian Review. As a noted authority on Czech history points out, “The use of these names creates problems for the student of the Czechs and their influences on Wilson, since the Czechs in America continued to call themselves Bohemians even after the start of the war, while the political exiles in Europe used the term Czech.” Otakar Odlozilik, “The Czechs,” in Joseph P. O’Grady, ed., The Immigrants’ Influence on Wilson’s Peace Policies (Lexington, Ky., 1967), pp. 207, 209.

- Thomas G. Masaryk, The Making of a State: Memories and Observations, 1914-1918 (New York, 1969), p. 92.

- Charles R. Crane, Memoirs (MSS in Russian and East European Archives, Butler Library, Columbia University), pp. S3, S3A (hereafter cited as Crane Memoirs).

- Masaryk, Making of a State, p. 8; Marcia Davenport, Too Strong for Fantasy (New York, 1967), p. 319.

- Crane Memoirs, p. S3A.

- Crane Memoirs, pp. 152-55, 168; C.R.C. to J.C.D., January 1914, Charles R. Crane Papers (Russian and East European Archives, Butler Library, Columbia University); David F. Houston to Charles W. Eliot, Dec. 1, 1916, David Franklin Houston Papers (Houghton Library, Harvard University); Edith B. Wilson, My Memoir (Indianapolis, 1938), pp. 100, 345; Masaryk, Making of a State, p. 682.

- Crane Memoirs, pp. 153-54; Houston to Eliot, Dec. 1, 1916, Houston Papers.

- Crane to President Wilson, May 18, 1914; President Wilson to Crane, May 21, 1914, Crane Papers; New York Times, Jan. 30, Feb. 3, 1914.

- Crane Memoirs, pp. 152-53; White House Memorandum, Mar. 2, 1917, Woodrow Wilson Papers (Manuscripts Division, Library of Congress, Washington, D.C.); New York Times, July 4, 1914.

- Houston to House, July 24, 1915, Houston Papers; Crane to House, summer 1915, Crane Papers; Phillips to House, July 31, 1915, Edward M. House Collection (Sterling Memorial Library, Yale University) ; New York Times, Feb. 23, 1915.

- Mary McDowell, “Tried in Her Father’s Stead,” Survey, Apr. 29, 1916, p. 116; New York Times, Apr. 28, 1916.

- H. A. Miller, “What Woodrow Wilson and America Meant to Czechoslovakia,” in Robert J. Kerner, ed., Czechoslovakia (Berkeley, 1940), pp. 71-74.

- Eduard Benes, My War Memoirs (Boston, 1928), p. 98; Charles Pergler, America in the Struggle for Czechoslovak Independence (Philadelphia, 1926), pp. 21-23; New York Times, Nov. 28, 1914.

- Emmanuel Victor Voska and Will Irwin, Spy and Counterspy (New York, 1940), pp. x-xii.

- Robert W. Seton-Watson, Masaryk in England (New York, 1943), pp. 33-34.

- Masaryk to Voska, Dec. 27, 1914, Wilson Papers.

- Voska and Irwin, Spy and Counterspy, pp. IS, 16; Lansing to Wilson, Dec 1, 1915, Personal and Confidential Letters to the President, Record Group 59, Department of State, National Archives (hereafter cited as R.G. 59, D.S.N.A.). For an account of Voska’s role in this affair see Barbara Tuchman, The Zimmerman Telegram (New York, 1958), pp. 72-75.

- Seton-Watson, Masaryk in England, pp. 96-100.

- Crane to J.C.B., Feb. 14, 1917, Crane Papers.

- Benes, My War Memoirs, p. 99.

- Masaryk to Crane, Mar. 11, 1915, Crane Papers.

- Masaryk to Roger H. Williams, Nov. 15, 1915, Crane Papers; Voska and Irwin, Spy and Counterspy, p. 16. Charles Pergler, who headed the American office of the Czecho-Slovak National Council, later informed Secretary Lansing that the “whole Czecho-Slovak movement originally was financed by subscriptions from America,” and that this continued to be their main source of funds. Pergler to Robert Lansing, Mar. 6, 1918, Files of the Committee on Public Information, D.S.N.A.

- Voska and Irwin, Spy and Counterspy, pp. 16, 200; New York Times, Apr. 22, Aug. 31, and Nov. 9, 1915.

- New York Times, Mar. 10, 1915.

- Wilbur J. Carr [for the secretary of state] to Charles L. Hoover (American consul in Prague), Mar. 2, 1916, file 364.64/3Sa, D.S.N A.; McDowell, “Tried in Her Father’s Stead,” p. 116; New York Times, Apr. 28, 1916.

- Mary R McDowell to Crane, Feb. 26, 1915, Crane Papers.

- William C. Penfield to Secretary of State, Apr. 8, 1916; Charles L. Hoover to Penfield, Mar. 11, 1916, file 364.64/41, D.S.N.A.; Richard C. Crane to Charles R. Crane, Apr. 24, 1916, Crane Papers.

- Masaryk to Crane, Nov. IS, 1915, Crane Papers.

- Masaryk to Crane, Nov. 29, 1915, Crane Papers.

- Charles R. Crane to J.C.B., Apr. 20, 1916; Frederick Dickson to Crane, Apr. 20, 1915, Crane Papers; Christian Science Monitor, Dec. 1, 1915, Mar. 3 and 5, 1916.

- Frank L. Polk (acting secretary of state) to Sabath, June 3, 1916, file 364.64/63 D.S.N.A.

- Apparently Crane was successful in publicizing the case as similar to that of the famed Edith Cavell, because many of the headlines which featured the affair carried captions similar to those used in the Edith Cavell case. New York Times, Apr. 9, 21, and 28, 1916. See also Denni Hlasatel, Apr. 19, 1916.

- New York Times, Nov. 9, 1915. For an account of Sabath’s later efforts to influence the president on behalf of Bohemian independence see Guido Kisch, “Woodrow Wilson and the Independence of Small Nations in Central Europe,” Journal of Modern History, 19 (1947): 235-38.

- Lansing to Wilson, June 28, 1916, Miscellaneous Letters Sent by the Secretary of State, R.G. 59, D.S.N.A.

- Denni Hlasatel, Apr. 21, 1916.

- New York Times, Apr. 21, 1916.

- New York Times, Apr. 28, 1916.

- This news was accompanied by “unbelievable, frightful” reports of new insurrections which had broken out in Prague, Pilsen, Tabor, and other Czech towns. It was reported that when such “anti-Austrian, antiwar” insurrections had occurred several months earlier, the Austrian government had made clear that they would execute the prominent Czech hostages then taken, in the event of recurrence of such insurrections. Information now available indicated that all Czech hostages were to be executed, including Miss Masaryk. Denni Hlasatel, Apr. 27, 1916. See also New York Herald, Apr. 27, 1916.

- Christian Science Monitor, Apr. 27, 1916.

- Secretary of State to Charles L. Hoover, Prague, Mar. 2, 1916, file 364.64/35a, D.S.N.A.

- Penfield to Lansing, Apr. 6, 1916, Hoover to Penfield, Mar. 11, 1916, file 364.64/63, D.S.N.A.; Polk to Julia Lathrop, Apr. 21, 1916, file 364.64/43, D.S.N.A.; Denni Hlasatel, Apr. 28, 1916.

- New York Times, Apr. 28, 1916. See also Christian Science Monitor, Apr. 21, 1916.

- New York Times, Apr. 28, 1916. See also Christian Science Monitor, Apr. 21, 1916; Chicago Daily Tribune, Apr. 21, 22, and 27, 1916. Denni Hlasatel, Apr. 30, 1916.

- Denni Hlasatel, Apr. 28, 1916; Christian Science Monitor, Apr. 24, 1916.

- McDowell, “Tried in Her Father’s Stead,” p. 116; Chicago Daily Tribune, Apr. 21, 1916. The Chicago piece was headlined, “Women of United States Urged to Save Alice Masaryk.” It was followed the next day by a two-column picture with an additional appeal. Chicago Daily Tribune, Apr. 22, 1916; New York Times, Apr. 28, 1916. The concern and efforts of American women in Miss Masaryk’s behalf were described in Denni Hlasatel, Apr. 20 and 30, 1916.

- Denni Hlasatel, July 21, 1916.

- Chicago Daily Tribune, Apr. 25, 1916. See also Denni Hlasatel, Apr. 30, 1916. Both Jane Addams and Grace Abbott had involved themselves earlier in representations to the State Department regarding the rumored massacre of Professor Thomas G. Masaryk in 1914. Addams to William Jennings Bryan, Aug. 30, 1914, file 76372/683, D.S.NA; Abbott to Louis F. Post, Dept. of Labor, Aug. 29, 1914, file 763.72/684, D.S.N.A. For Grace Abbott’s initial efforts in Miss Masaryk’s behalf see Denni Hlasatel, Apr. 20, 1916.

- Christian Science Monitor, Apr. 21, 1916.

- For a complete record of the incoming appeals see documents in files 364.64/45-61, D.S.N.A. See also Masaryk, Making of a State, p. 92.

- Richard Crane to Charles R. Crane, Apr. 24, 1916, Crane Papers; New York Times, Apr. 28, 1916.

- Herrick to Polk, Apr. 26, 1916, Polk to Herrick, Apr. 28, 1918, file 364.64/62, D.S.N.A. This was the suggestion frequently made by the secretary of state to prominent individuals, as well as organizations. For example, see Lansing to Dr. Sophonisba Breckinridge, University of Chicago, Apr. 27, 1918, Lansing to Bohemian National Alliance of America, Apr. 28, 1916, Lansing to Women’s Trade Union League, Apr. 28, 1916, files 364.64/46, 364.64/49, and 364.64/50, D.S.N.A. See also Denni Hlasatel, Apr. 28, 1916.

- Chicago Daily Tribune, Apr. 27, 1916.

- Denni Hlasatel, Apr. 27, 1916.

- New York Times, Apr. 28, 1916.

- Denni Hlasatel, Apr. 30, 1916.

- Chicago Daily Tribune, May 15, 1916; Denni Hlasatel, May 10, 1916.

- New York Times, May 9, 1916.

- New York Times, July 21, 1916. The news of her safety was also reported on the front page of the Chicago Daily Tribune, July 21, 1916.

- Penfield to Lansing, Aug. 2, 1916, file 364.64/100, D.S.N.A.

- New York Times, Aug. 13, 1916.

- New York Times, Aug. 20, 1916. The Christian Science Monitor, Aug. 21, 1916, reported that she was freed on July 3.

- Denni Hlasatel, Aug. 21, 1916.

- Masaryk, Making of a State, p. 92.

The author of this article, Betty M. Unterberger, noted that she wishes to acknowledge with gratitude the research support of the American Philosophical Society and the Organized Research Fund of Texas A&M University.

Original Source of this article: The Slavic Review 33, No. 1 (1974)

xxx

When World War I broke out in August 1914, Alice’s father Thomas Masaryk—by now one of the leading voices of the Czech nationalist movement—escaped with his younger daughter Olga Garrigue Masaryk , first to Italy and then to Switzerland. After his “declaration of war” on behalf of a Czech nation that thus far existed only in theory, his entire family began to feel the growing anger of Vienna’s Habsburg regime. Thomas was sentenced to death in absentia for his treasonous actions, and his wife Charlotte, whose health was fragile at best, was harassed by the authorities. Accused of having engaged in illegal Czech nationalist activities, Alice Masaryk(ova), along with Hana Benesova, the wife of her father’s close associate Eduard Benes, was interrogated for two weeks in Prague, and then moved to a prison in Vienna. Alice was incarcerated there for eight months, and a massive pressure campaign from abroad was undertaken to secure her release. Her father wrote to many influential Americans about his daughter’s plight, including a letter to UCSS director Mary McDowell in April 1916. Despite her declining health, Charlotte provided her daughter with moral support by writing to her several times a week. A petition signed by 40,000 Americans from all walks of life went to the Austrian authorities. In addition to Mary McDowell, Jane Addams, Florence Kelley and Lillian Wald were among the prominent individuals involved in the petition drive. A significant factor in Masaryk’s release from prison would be the involvement of Julia Lathrop, chief of the Children’s Bureau in the Department of Labor, who was at the time the highest-ranking woman serving in the U.S. federal government. Lathrop petitioned the U.S. State Department to intervene with high officials in Vienna on Masaryk’s behalf. The pressure was effective, and Alice Masaryk gained her freedom on July 3, 1916.

Paragraph source: Encyclopedia Britannica

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Thank you in advance!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.