The following article entitled Czechoslovaks, Yankees of Europe appeared in a very old issue of National Geographic magazine from August of 1938. A wonderful 52 page article with 30 “cyclorama” color photographs. It is an excellent piece which shows us the Czech lands pre-World War II. As the title suggests, author John Patric found a striking resemblance between first republic Czechoslovakia (1918-1938) and the Yankee culture of the United States of America.

To foreigners, a Yankee is an American.

To Americans, a Yankee is a Northerner.

To Easterners, a Yankee is a New Englander.

To New Englanders, a Yankee is a Vermonter.

And in Vermont, a Yankee is somebody who eats pie for breakfast. ;)

Today, we’re looking at Czech Yankees and by that we mean to include all of the people that live(d) in the Czech lands.

The following article was written 81 years ago, and reading it I wonder, is the American “Yankee spirit” of the Czech Republic still alive today? Do Czechs consider themselves a part of Western culture? What about Masaryk? Are his humanist ideals still included in the core of shared beliefs in Czech Republic or is he all but forgotten by the new generation? These are interesting things on which to reflect after reading this long piece and then considering the Czech Republic of today…

We hope you will take the time to read it in its entirety as it paints a beautiful picture of our ancestry and the places and people of the time… Enjoy!

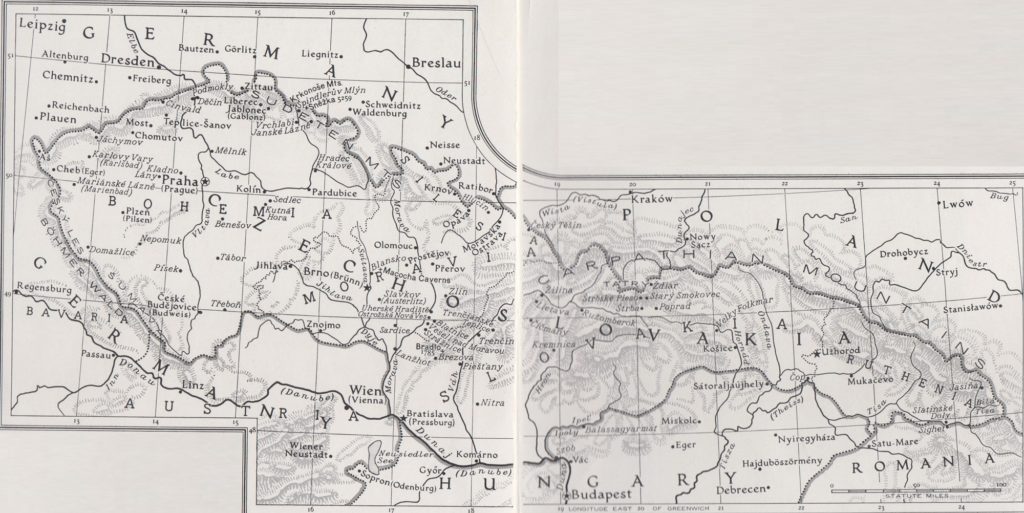

“Western Czechoslovakia is a Slavic peninsula in a sea of German peoples.” The elongated Republic, its government patterned after that of the United States, lies in the very center of Europe, almost surrounded by mountains. From industrial areas in the west it stretches for 600 miles eastward to a region of primeval forests and primitive farms. Its formation, with the help of the Allies after the World War, was the realization of a long-lived dream of restoration. The Kingdom of Bohemia, larger than the present province, was old and still powerful when Shakespeare laid part of his play, The Winter’s Tale, on mythical deserts near its nonexistent seacoast.

The Czechs, an ancient Slavic race, have lived in what is now central Bohemia and Moravia for nearly 20 centuries. Around their frontiers are Germans. The year the Pilgrims landed from the Mayflower in New England, Czechs lost their freedom. When they regained it three centuries later, on October 28, 1918, the Franz Josef railway station in old Prague was renamed for Woodrow Wilson. Today the Sudeten Germans appear often in newspaper headlines; their name is derived from the Sudeten Mountains in northern Bohemia and Silesia. Slovakia and Ruthenia, the eastern provinces, were parts of Hungary for 1,000 years. Though dominated today by Slovaks and Ruthenians, they also contain Czechs, Jews, Poles, Germans, Gypsies – and 700,000 Hungarians. Some paper money uses five languages on one bill.

Czechoslovakia writhes lizard-like across the map of Central Europe. Fifteen million people occupy an area smaller than Illinois. Three and a quarter million are Germans, most of whom live near the 900-mile frontier that separates Bohemia, Moravia and Silesia from their former overlords, Austria and Germany.

Of the 14 major political parties in Czechoslovakia, four are German. The Sudeten Party, largest numerically, takes its name from a mountain range in northern Bohemia. Each Czechoslovak political party holds seats in the two-house national legislature in exact proportion to the number of its voters. None has even a near majority. Unless a citizen is under 21, over 70, sick, or more than 20 miles from the polls on election day, he must vote, pay a fine, or go to jail. Balloting is strictly secret.

Slovakia and Ruthenia, containing about 700,000 Hungarians, were owned for a thousand years by Hungary, where flags droop always at half-staff, 20 years after the World War, for lost lands and peoples it hopes someday to regain.

From Lynn to Zlin

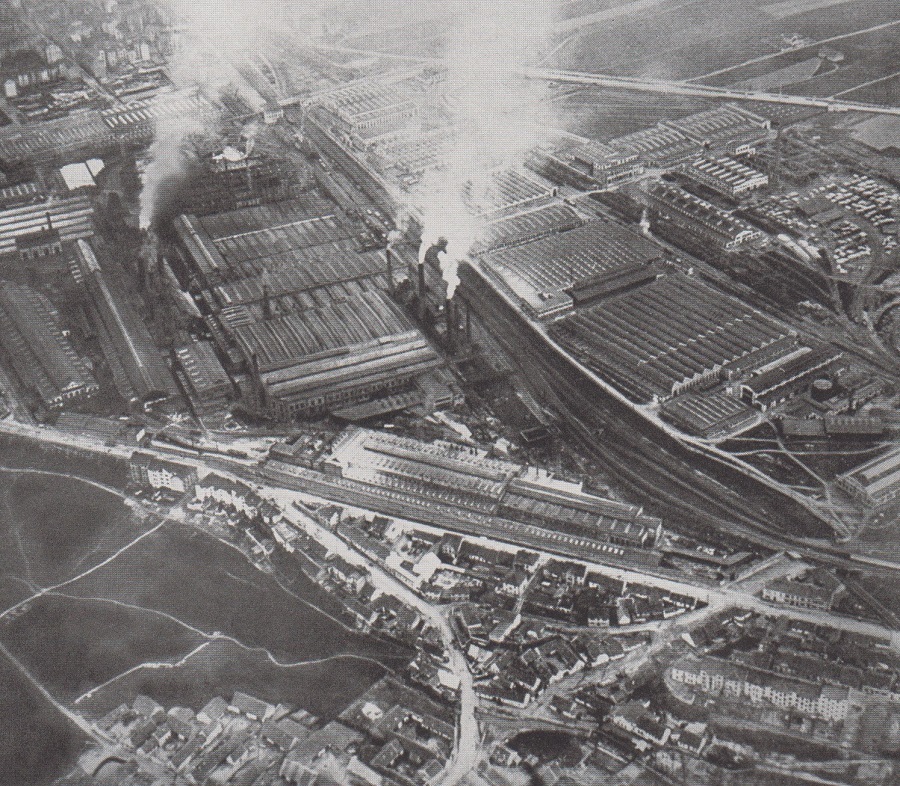

Though I was to see woodsmen in costume cutting logs into lumber with handsaws, living in chimneyless houses, and for shoes wearing a single piece of leather tied to each foot with thongs, it was in Zlin that I became convinced that Czechoslovaks are, in effect, the Yankees of Europe. One midwinter day, immediately after my arrival in Czechoslovakia, I went to see the immense Bata shoe factories, industrial symbol of a national era.

Thomas Bata (pronounced Bat-ya), with several of his workmen, went to the United States in 1904, and they all got jobs as shoemakers in Lynn, Massachusetts. Returning to Zlin, he introduced American methods into his little factory. Today there are 61,000 Bata employees scattered over the earth.

As I was waiting for my friendly guide in an office on the top floor of one of the factory buildings, the whole thing -, desks, stenographers, telephones, and all- suddenly dropped toward the basement. Unperturbed, everybody went on working.

We stepped out at the ground floor, and rode to the executive offices on an intraplant omnibus, past buildings plastered with such mottoes as:

- Hats off to work.

- Unambitious wife – a lazy husband.

- The world needs 1,000,000,000 pairs of shoes.

- Pay cash – don’t borrow.

- Dogged does it.

J. A. Bata, brother and successor of the founder, was then flying across India, selling shoes. D. Cipera, the general manager, showed me his chief’s office, where a clock ticked off the time of a dozen world cities, and where a pad of outline world maps, some six feet across, crayon scribbled, hung behind the executive desk.

Telephone Hookup with the World

On the desk stood several telephones, one a loud-speaking instrument, and a microphone connected with a public-address system in factory buildings. Lights flashing under a glass map of the works would indicate which workers were listening.

Annually, 250,000 long-distance telephone calls go through the Bata exchange; there are factories in eight countries, sales offices almost everywhere shoes are worn. Calls to distant cities are flashed on a screen in Bata’s office. He may pick up a telephone and join the conversation.

”Over there,” Cipera explained, ”the new 16-story administration building is going up. This is too small. In the new building, Mr. Bata’s office, and mine, will be built in elevator cages so heavy that it will take two sets of the most powerful American machinery to lift each one.”

”How does it work? For example, if I must call buyers into conference, I press a button, start my office moving to their floor, continuing my work all the time. When my office gets there, I ring for the buyers to come in. If Mr. Bata wants to visit the sales force, he can dictate or telephone as his office goes to them. Good men are hard to get; saving time for those we have is like having more of them.”

With a group of employees, whose lunch period is two hours, I ate in the dining room of a large Zlin department store.

When the noon siren blows 18,000 Bata shoemakers stream past time clocks at the factory gates, beneath signs that suggest “first of all, we should be properly shod.” Near this entrance, when the author visited Zlin, a new 16-story administration building was being erected, with executive offices built in elevators to save time. Some employees go home for the two-hour lunch period; others flock to the immense dining rooms in the ten-story department store in the background, and see a movie afterward. Hours of employment are from 7 to 12, and 2 to 5.

After lunch, some workers saw a movie. The largest cinema theater in Central Europe stood near the factory gates where even J. A. Bata punches in like the humblest apprentice. Though admissions run as high as 50 cents or more in Praha, here all seats were 10 cents. Only four years old, the theater building was already too small, and plans for a new one were being drawn.

”One low price” is a principle applied to every Bata enterprise. Best rooms and bath in the new Zlin hotel cost 80 cents. That night I had dinner with Bata’s safety director. He had been a workman earning $5 a week (equal in Zlin, though not in Czechoslovakia generally, to about $20 in the United States) when he won a “safety first” contest and a new position.

Ridicule Feared More Than Injury

Though shoe machinery is run by 24,000 self-contained electric motors instead of exposed line shafts and pulleys, careless men were often hurt. My host made a lifelike dummy. When a workman is injured now, the dummy is bandaged like the victim and hung near factory gates for workers to see. It is labeled, perhaps: “I am Jan Sloupa. I tried to fix a riveter without cutting the power. Look at me now!”

Because men seem to fear ridicule more than injury, the idea works.

The safety director’s six-room brick house, with garden, built-in garage, and telephone, rented for $1.60 a week from the company. When he was earning less, he lived in a smaller house, modern also, where weekly rent was 50 cents.

After dinner we saw a night session of the Bata college, its physical plant the equal of many a small college in America.

Non-employees who live in Zlin, or who come here to study, pay a small fee. Anyone is welcome. Employees pay for courses that have no bearing on their jobs; the company pays for those that do.

The next morning was dark, damp, and snowy. The home of Thomas Bata’s widow stood in wintry isolation in a park at the end of an icy street. A wealthy woman, she remains in the city her husband built. She lives in a house well-furnished now, though “bare for many years,” she told me, laughing, ”because whenever I wanted a picture or a bookcase, Thomas would mention someone in the factory who operated an obsolete machine.”

Mrs. Bata was flying to Praha; she invited me to accompany her.

By Plane to Praha

Early that murky afternoon I went to the busy airport. The three motors of a giant British-built plane were idling, warm and ready, despite the weather, to lift us over the white hills of Moravia to Praha. Near us, like chicks, stood a fleet of the Bata-built airplanes.

Tanks lead a practice charge across rugged terrain. Czechoslovakia’s irregular frontier cannot be defended by battleships. It is too long for a complete chain of subterranean forts such as France has built on her German border. The exposed democracy has relied on pacts with France and Russia, membership in the Little Entente, a conscripted army, a crack air force, and the Skoda works.

Foreign customers must be friends or allies of Czechoslovakia to obtain a government permit to patronize the munitions works at Plzen. Romania and Yugoslavia, fellow members of the defensive alliance, the Little Entente, are large buyers. So is China. Specializing in heavy guns, the plant likewise manufactures motorcars, tractors, railroad equipment, ships’ propellers, and machinery.

We flew over wooded hills and cultivated valleys. This country, despite vast, uninhabited forest and mountain lands, is, next to Germany, the most densely settled in Central Europe. That is why Czechoslovakia exports manufactures and imports food.

When the Nation gained its freedom, this old factory district of Austria-Hungary lost many markets behind tariff walls that subdivide the former empire today.

As we sped over tile roofs, I fancied I could smell the smoke of fagot fires, drifting upward from chimneys of snug, thick-walled houses, where women even then were busy with churns and knitting.

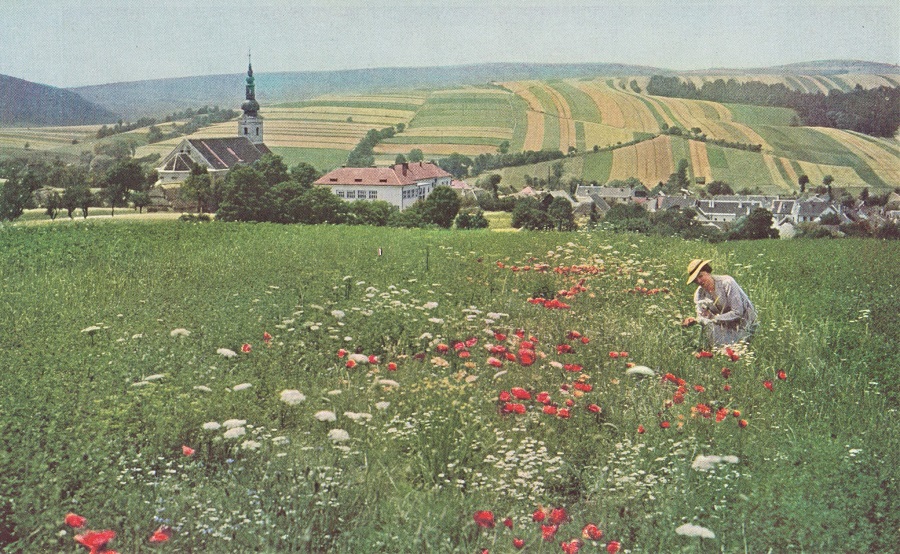

Strips of hillside fields about Velky Folkmar are owned by frugal, neighborly husbandmen, whose barns and storerooms are part of their neat, whitewashed houses. In the distance a motor road winds into the foothills, toward the High Tatras of Slovakia. Schoolgirls, resting after a climb on a summer afternoon, will soon be old enough to work in the fields with their fathers.

I could see files of geese in snowy streets, and wellheads and straw stacks in the yards. I could even see the chickens that perch on warm manure piles when days are cold and spiritless and there are only snow and ice to scratch in.

Now a freshening wind flattened the blue smoke plumes that had curled so lazily from the chimneys. Our ceiling lowered; sky and storm closed down. Snow whipped past cabin windows. Houses, fields, and trees were blotted out. We were flying blind and began to climb.

At a mile of altitude, it was much colder; my breath froze on the cabin window. At 7,000 feet Mrs. Bata tossed me a fur robe. At just under two miles we burst out of the fog like an express train from a tunnel. Here, except for the temperature, it might have been summer. Looking out at the sunlight blazing fiercely across the horizon, I forgot the drab winter day below.

A V-shaped fleet of fighting aircraft crossed our course, high above us. Had we been an invading bomber, we could have hidden in the billowy fog below us.

Glimpsing flying buttresses of its church of Santa Barbara, I recognized Kutna Hora. Reading of that place, I had been reminded of a ghost silver town in Nevada.

Rich mines and a mint had made it a center of art and architecture in the Middle Ages, when it was second city in a great nation of that time. It was also the second seat of the kings of Bohemia. Bitter history was enacted there 500 years ago, when silver miners in religious zeal tossed hundreds of dissenters down their deepest shafts.

Scarcely more than a village now, Kutna Hora mints money no longer; coins of the Republic are struck in Kremnica and come to Kutna Hora in travelers’ pockets.

A Ghoulish Masterpiece

Most visited shrine today, perhaps, is the charnel house of a Cistercian abbey in the adjoining village of Sedlec, built of human bones from chapels to chandeliers. In 1318, a plague provided 30,000 skeletons to start the masterpiece of ghoulish art. War became its patron after that; there are skulls cleft by the sword, smashed by the mace, and drilled by bullets. Meticulous monks, who sorted bones for size and shape, made ingenious use of misshapen ones where unusual patterns required them.

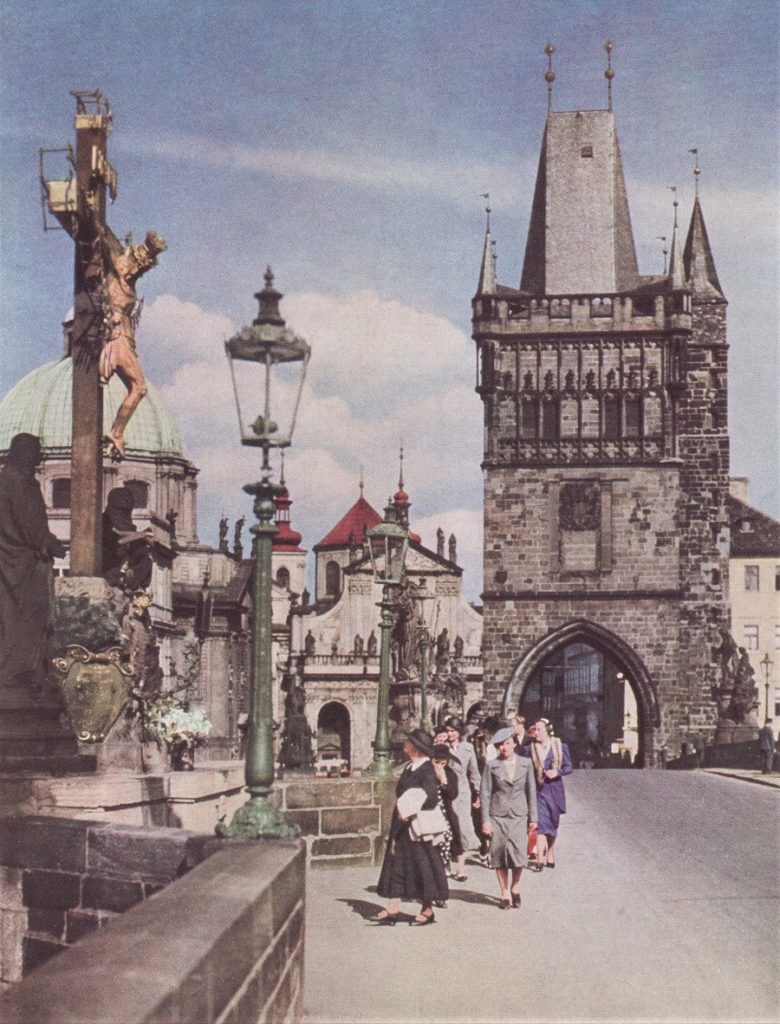

To let me glimpse Praha from the air that winter evening, our pilot swung his ship in a circle before landing near the city. Streetlights were already burning; their beams shot skyward through thin, low-lying fog. A hundred towers, sharp-tipped and delicate, pierced and silhouetted themselves against the misty veil that lay so lightly white over old Prague – a fairytale in stone.

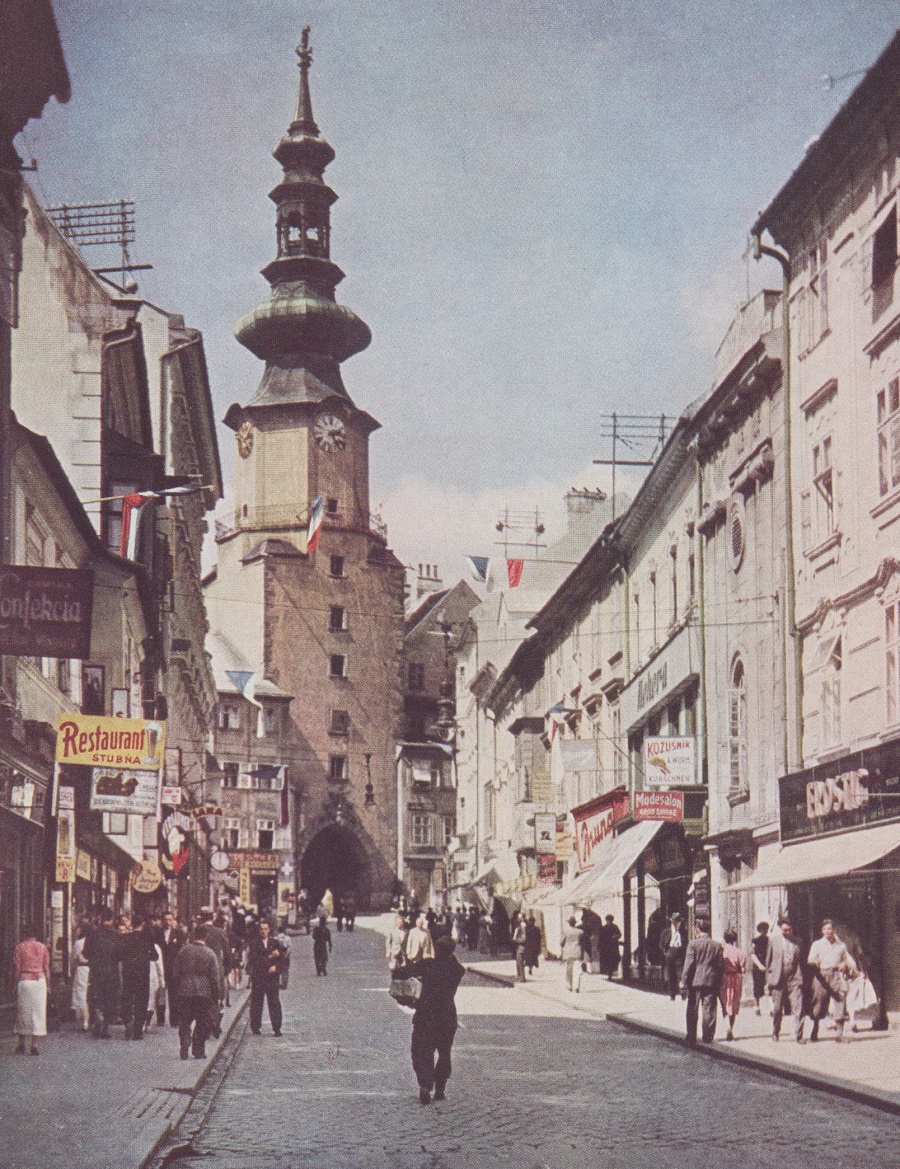

“Hundred-spired, golden Prague,” often called “Rome of the North,” owes much of its surviving medieval sculpture to pious King Charles IV of Bohemia, who lived 600 years ago. The Bohemian kingdom lost its freedom about three centuries later, at the time the Pilgrims landed in America. The next year, heads and hands of Czech patriots, impaled on spikes, were displayed as a grim warning above this tower gateway. After 300 years as a subject people, Czechs, along with Slovaks, Germans, and Ruthenians, were incorporated in the Republic of Czechoslovakia, formed as a result of the World War. Praha today is twice its prewar size; many of its newer streets and business buildings resemble those of the United States.

Far below us the Vltava River meandered through the town beneath thick ice.

This outdoor cafe has a swimming pool and, for rainy weather, an indoor restaurant. The double-track railway links Praha with Plzen, home of Pilsner beer and the immense Skoda munitions works. North of Praha, the river joins the commerce-laden Labe (Elbe in German).

On Hradcany, a hill above it, stood the Castle of Praha.

The castle of Praha was once the residence of Bohemian kings and noblemen. St. Vitus Cathedral rises from the immense courtyard within it. Today the extreme left wing is occupied by Eduard Benes, President of the Czechoslovak Republic.The Chief Executive’s guards still wear the uniforms of Russian, French, and Italian armies in the World War, under whose banners patriotic legends fought to liberate the country. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs maintains some offices in the old castle, but many of its old-fashioned ornate chambers are closed and locked. Hradcany is the name of the entire hill, and thus of the Executive Mansion. In the foreground is Charles Bridge, lined with statues of saints. Log jetties protect the piers of the 600-year-old span from ice jams in the spring.

The Bohemian prince-saint who is “Good King Wenceslaus” to English carol singers founded St. Vitus more than a thousand years ago. Hradcany epitomizes the stormy story of Bohemia: for in every historic Czech drama some scenes were here.

Below the castle, across the river, is “Old Town.” Its medieval houses and masonry pinnacles are preserved in the heart of a changing city that is twice its prewar size. Semi circling Old Town is a shopping district. Here a few new and many remodeled buildings are sprinkled among structures that, except for their shop-lined arcades, resemble the older parts of many American cities.

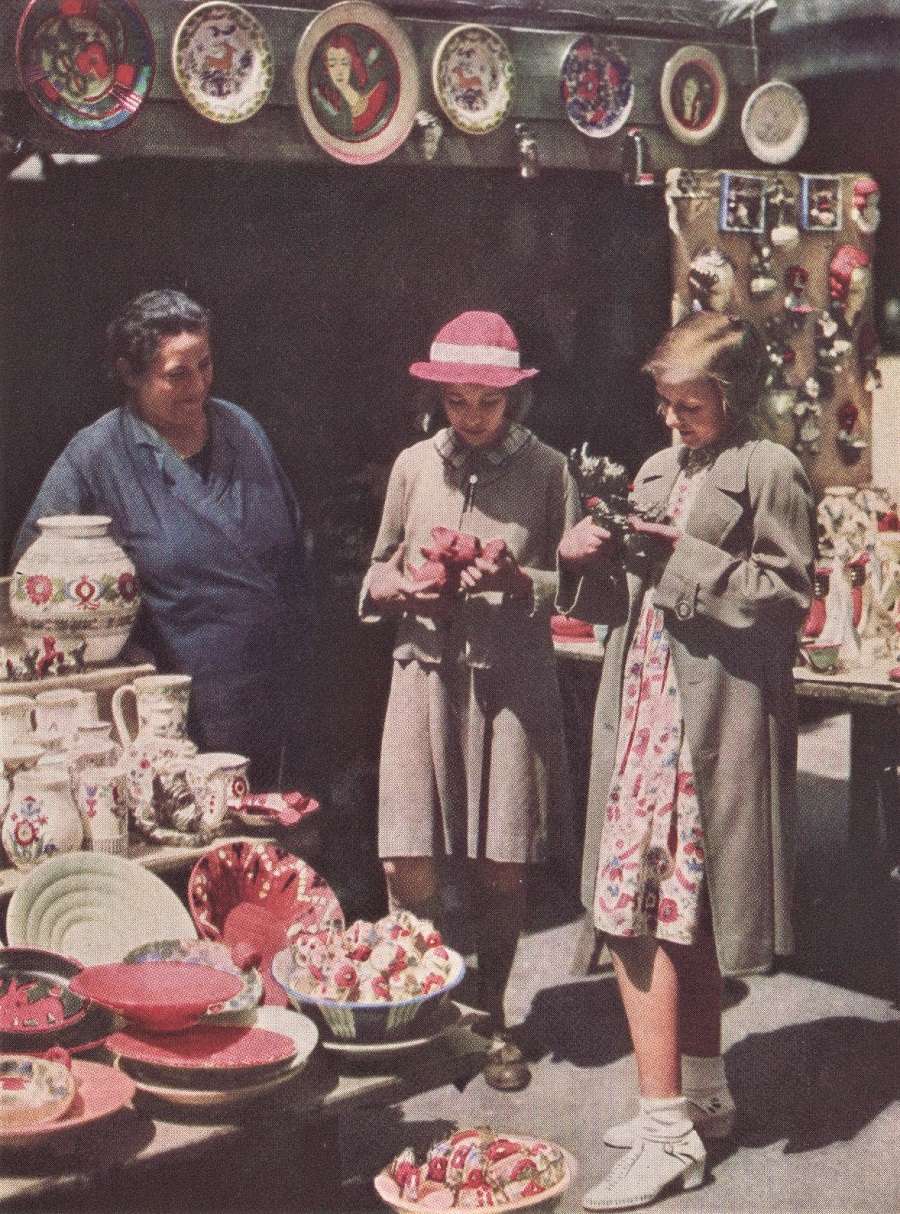

Two city girls, examining Czechoslovak porcelain Scotties, dress more simply than their country cousins. Merchandise is sold from portable shops like this in the marketplace in Praha.

Fifteen minutes later I was sitting in the coffeehouse of a Bata shoe department store in Wenceslaus Square, drinking coffee-and-milk with thick whipped cream, eating hot jelly doughnuts, thawing, and thanking my hostess.

A statue of Good Kind Wenceslaus, of whom English carolers sing at Christmas, faces down the square. Less than half a mile long, the street, called Vaclavske namesti, is the finest in the Republic. It is a favored location for hotels, automat cafeterias, coffee shops and stores. Movie theaters are usually built in the basements.

At the Prague English Club I met George, who knew Bohemian history, knew his city, and spoke my language well. He walked with me one cold evening across Old Town. Some narrow streets were wider than the strip of dull sky above them, for lower floors of the adjoining houses receded like Andy Gump’s chin.

Beneath upper stories in one arcade of shops we paused to look at a hardware store window filled with low-priced gas masks. All citizens of Praha are required by recent regulations to keep them on hand.

Bivouacked in border towns bright with costumed lasses, the conscripted Czechoslovak Army is ready for what troubled times may bring, especially if it’s Pilsner in a frosty, battered mug.

We continued along wider streets, between palaces of the past. Imposing facades of some were frescoed: outlines of elaborate pictures had been scratched deeply, long ago, into the wet plaster.

Above some portals remain the name plates of medieval times – easily recognizable statuettes. “The Sign of the Golden Angel” glitters protectingly over the door of what is now a restaurant. At the Sign of the White Swan is a bakery. Nearby are the Saint and the Dragon, the Madonna, and the Three Cranes.

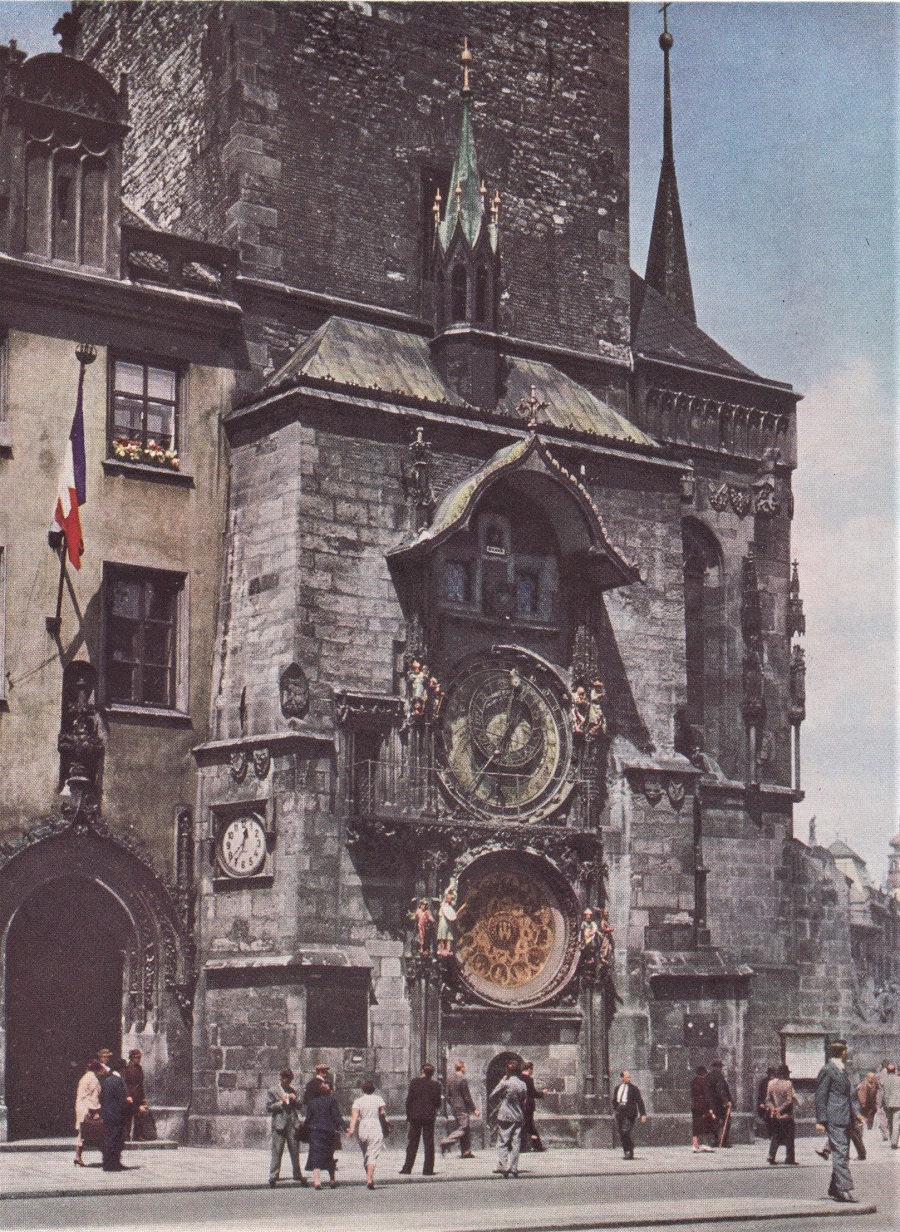

Presently we came to Old Town Square, with its Tyn Church and astronomical clock. Here 27 Bohemian leaders were executed in 1621 by victorious Hapsburgs whose rule was to continue for three centuries.

Striking landmark in Praha is Tyn Church, built more than 500 years ago. Its name comes from the old Czech word for the fence or stockade that stood here in medieval times when a smaller edifice occupied the site. In Old Town Square rises a memorial to the religious reformer. His death at the stake at Constance in 1415 started the bitter Hussite Wars that interrupted the completion of Tyn Church for half a century.

A Queen Was Too Frivolous

“Perhaps reformers went too far,” George remarked. “The wife of the last ruler of Bohemia was unpopular partly because she had no settled hours for meals or prayers, and because she wore low-necked dresses.”

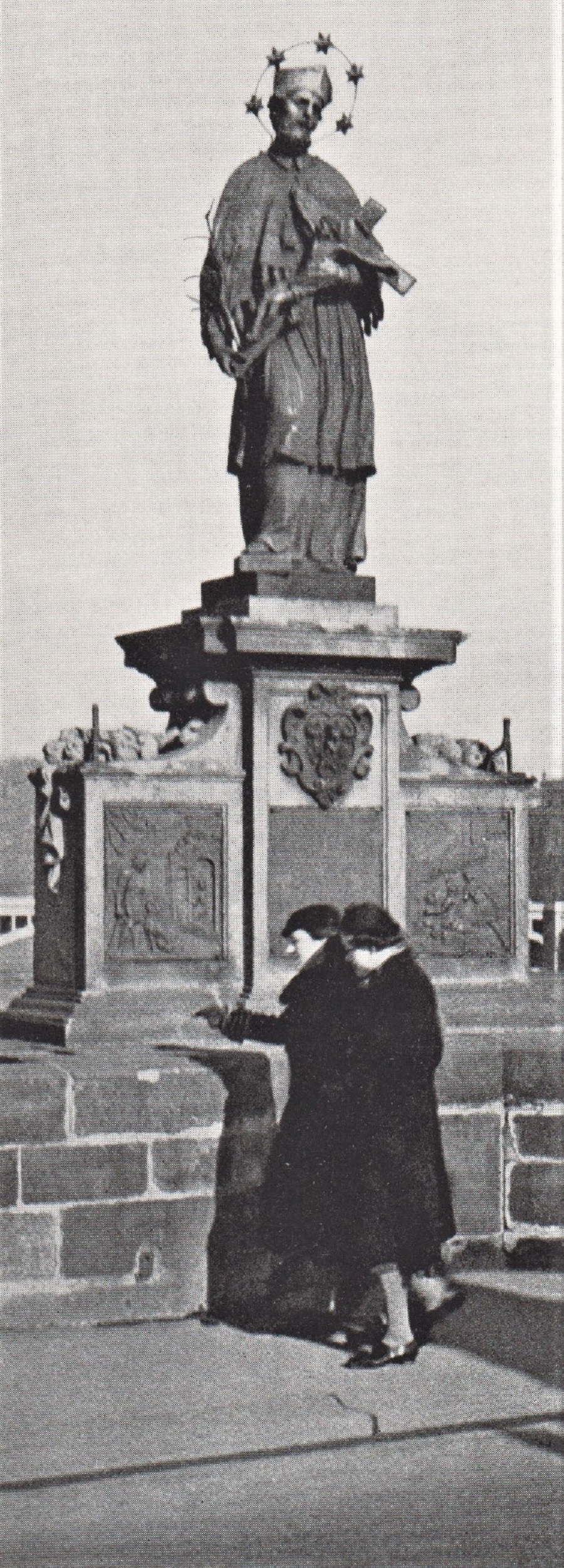

We walked across Charles Bridge, between the ranks of cold stone saints, and continued our cold journey toward Mala Strana, an old section below Hradcany that is called “Little Town.” Noblemen’s palaces there have become foreign legations. The German Legation was guarded by police.

Our goal was a 700-year-old basement restaurant. Wenceslaus IV, they say, used to come down the path through the woods from Hradcany with a lantern, sit by a fireplace there and sip a drink called mead, or honey beer.

By our corner table was a little sign: “Here meets the Felix Table Society,” with a picture of a comic-strip cat.

George explained an old Bohemian custom. “As a rule, we don’t invite friends to our homes. We see them in restaurants or coffeehouses. Little groups, calling themselves ‘table societies,’ meet regularly, often for years, in a certain restaurant. One is gathering now; maybe it’s the Popeye the Sailor Society.”

A Table Society Meeting

Singly and by twos came members, all forty-ish, until 20 men and women had gathered around one long table. They ordered beer. Sometimes a “chill remover,” a polished metal gadget shaped like a short candle, was filled with boiling water and hung inside the stein.

Two men debated across the table. “They’re arguing politics,” George said. “The big fellow disapproves of the administration. He thinks it represents so much compromise between so many parties that no legislation of real importance is ever passed. He seems to be in the minority.”

There was singing as steins were drained and filled again. From the street came an old man, a box slung from his shoulders. He shook snowflakes from his whiskers.

“Sardinkar!” shouted a diner.

He came to us at last, the sardine seller, displaying tantalizing fish filets, and pickles made of little onions, turnips, cucumbers, and fine white cauliflower. For ten cents he gave me samples, plucked carefully from jars with his tongs.

Every night he visits twenty little inns, he said. Proprietors welcome him; he revives drooping thirst. Salty fish he buys; his wife makes the pickles. Cauliflower, he told us, was most difficult to preserve.

“Can you earn much?” asked George.

“It’s a bad night,” said the sardinkar, proudly, “when I don’t make 30 crowns.” That is a little more than a dollar.

Though political arguments do not concern Czechoslovak police, crime does. At central headquarters of criminal investigation a few days later, I was shown a comprehensive record that lists everyone. “It has uses other than criminal,” the director said. “A woman may locate a lost sweetheart, or a man can find the fellow who borrowed 50 crowns and left town.” Without giving us his reason, any citizen may ask us to locate anyone.”

Student detectives may study a museum of past crimes and the methods of solution. “Usually it’s the same sordid story,” the director remarked, ”though occasionally there’s an amusing criminal, like the carpenter who wasn’t afraid of ghosts.

“He got reduced rent for staying in a house after frightened fellow tenants moved when they kept hearing strange tappings at night. Trying to lease the house cheaply, he aroused suspicion. We found this little wooden drop hammer in the garret. It worked with a hidden string.”

“Because tobacco is a government monopoly, we watch for illicit cigarettes. One man bought cheap, strong smoking tobacco, mixed it with autumn leaves, made cigarettes and sold them in counterfeit packages. We seized his machine.”

One day I was lunching with the editor of a Chicago Czech daily, who was visiting in Praha, and with a diplomat from the Foreign Office. We ordered plum dumplings.

Roast Goose and Plum Dumplings

The waiter brought greasy pellets of dough as big as ping-pong balls, with dishes of melted butter, spiced sugar, and grated cheese. The diplomat halved a dumpling and the plum within it, then dipped each half in butter and sprinkled cheese and sugar over both pasty, plum-lined hemispheres. The result was surprisingly good. Roast goose, plum dumplings, and beer are specialties of the country.

That afternoon I drove with the editor through farm and frosty forest to Kladno, coal mining town west of Praha. “These are beautiful roads in spring,” he said, “when trees are blooming.” Combining fruitfulness with shade, apple and pear trees are planted along Bohemian highways and leased to provide funds for road repair.

Our Kladno destination was a cottage on a narrow street, where was born a boy who became mayor of Chicago and died in 1933 by a bullet intended for President-elect Roosevelt.

So spoke Anton J. Cermak to Franklin D. Roosevelt when the Mayor of Chicago lay fatally wounded in Miami, Florida, in 1933, by a bullet intended for the President-elect of the United States. A bronze plaque, gift of Chicago’s Spartan Athletic Club, marks Cermak’s birthplace in Kladno.

We examined the humble house. An old woman is paid by the town of Kladno to care for the shrine. Everybody remembers Anton Joseph Cermalz. “I was with him once,” the editor said, “when he made a speech, in Czech with an American accent, here in the town square. He knew how little money the kids had; so, he bought a hundred dollars’ worth of five-crown pieces – more than 500 – and gave them away.”

If liberty were threatened, the non-militaristic Sokol could mobilize most of its 800,000 members. Inspired by the Italian struggle for independence at that time, the movement was organized in 1862 to promote discipline, strength, and national solidarity when Czechoslovaks were subject people.

Returning, we paused to visit a country castle at Lany, near Praha, where lived Thomas Garrigue Masaryk until his recent death. He had been President from the beginning to December 1935, of the democracy he built. For some years his successor, Eduard Benes, came every week for lunch and advice from his old friend and mentor – wise, liberal, and tolerant, for having lived and loved liberty so long.

President Eduard Benes (in white), visiting the shoemaking town of Zlin, addresses a crowd from a stand beside the Bata motion picture theater. Beneath the fighting motto is the coat of arms of Czechoslovakia, with two double-tailed Czech lions holding a shield composed of the coats of arms of its historic lands. The double cross represents Slovakia; the bear, Sub-Carpathian Russia, or Ruthenia; the checkered eagle, Moravia; the lion, Bohemia; the black eagle with the crescent moon on its breast, Silesia; and the lowest three the old Bohemian crown lands of Tesin, Opava, and Ratibof. On the cinema wall a map of the country shows its principal waterways and urges their commercial development.

Independence Born In Washington

In a hilltop cemetery beyond the village we visited a grave marked by a stone as simple as those around it, except for its bronze lantern for evenings when graves are lighted. There rests Charlotte Garrigue, the American girl Masaryk met in Leipzig and married more than 50 years ago.

Long before the Czechoslovak Republic existed, Charlotte Masaryk gave to her professor husband a love and understanding of the United States. So great was his devotion that he took his wife’s maiden name for his middle one.

Masaryk wrote the Czechoslovak Declaration of Independence after a talk with Woodrow Wilson at Washington, D.C., in 1918. He did the actual writing in his rooms on 16th Street, the thoroughfare upon which the headquarters of the National Geographic Society are located.

Constitution Day is celebrated only once every four years, because that document was ratified February 29, 1920.

Next day I chatted with Karel Capek. His play, R.U.R., gave to the English language the word ”robot,” from the Czech robota, “to work without pay.”

I found him late one evening, characteristically hard at work in a Praha newspaper office. I suggested that he invent an “editorial robot.”

“Do Americans still use that word?” he growled, pleased.

“We’ve given you plenty of slang in exchange,” I said.

Capek laughed. “This country’s getting more like the United States every day.

“His new play, The White Plague, was being discussed everywhere. Seats were sold out for weeks in Praha; I saw the drama from a chair in the aisle.

A fatal disease, attacking only the middle-aged, creeps into an imaginary land ruled by a dictator. First dread symptom is sudden loss of feeling in some part of the body. The vibrant-voiced ruler has spurred his people to conquest. Young men train for war; their leader is radiant with courage.

The plot hinges about a shabby doctor who discovers a cure for the White Plague. He keeps his secret, cures humble sufferers, but refuses to help munitions makers and ambitious bureaucrats.

Frozen River A Busy Place

In winter people cross the Vltava on the ice. There is always activity; men with shoes wrapped in gunny sacks stand on boards and fish hopefully through holes. Others harvest ice cakes. Some skate to calliope music. Boys coast across the river from steep slopes beside it.

If I became cold, I could sit in a riverside coffeehouse as long as I liked. These cafes acquire the character – businesslike, urbane, or gay – of their clientele. In them students work, journalists write, businessmen close deals. Patrons play chess, checkers, or cards. Many read papers and magazines from the periodical library each coffeehouse maintains.

Most movies in Praha are in large cellars beneath store and office buildings. Patrons descend to the balcony. The closer to the screen the cheaper the seats. All seats for each performance are reserved. Latecomers are few; they may not see part of the next show without new tickets.

One corporation owns and rents to producers the film studios where Czech pictures are made on a high sunny hill near Praha. Anny Ondra, Czech star, wife of Max Schmeling, was working on the set at the time of my visit. One of her two leading men spoke German, the other Czech. She was fluent in both. Each scene was recorded twice, in German and Czech.

The Mountains of a Giant

Because it was winter, I did not go to Karlovy Vary, the old spa called “Karlsbad” by the Austrians, nor to nearby Jachymov, long called “Joachimsthal,” where bathing waters are radioactive, and where radium is produced from uranium ore. Joachimsthal silver once was minted into thalers, forebears of the dollar. (See “Geography of Money,” by William Atherton Du Puy, NATIONAL GEOGRAPHIC MAGAZINE, December. 1927.)

Trekking from the farm with baskets and produce carts, and dressed in Sunday finery, country folk near Domazlice combine marketing with churchgoing, thus saving a trip to town.

Softly stuffed with down, feather beds are piled with pillows in the parlors, for display and for special quests to use like quilts. Braided ringlets of the Lanzhot girl’s headdress represents the work of almost two hours.

Relaxing after services, groups gossip in a cobbled square of Domazlice, one of the few communities in Bohemia where folk costumes survive. The women will also do their weekly marketing and perhaps shop for red dress material while in town. The old frontier village is on a road to Bavaria, not far from the German border.

Tinted wax, in old spoons fixed to wooden blocks, is melted by alcohol flames. Dipping their needles into the hot liquid, women of Ostrozska Nova Ves draw complicated patterns directly on the shells. Other villagers paint designs with colorless parafin, then dip the eggs in dye, which stains only the untreated surfaces. Bright and elaborate folk dress, flowers painted on furniture, hand-worked tablecloths, and calcimined cottage walls typify household industry in rural Moravia.

Instead, I went to the Krkonose, called Riesen Gebirge, or Giant Mountains, by the Germans, not for their mile of altitude, but for Krakonos, a giant in Czech folklore, whose kingdom they are. Krakonos, they say, likes to stop millwheels, climb into tired travelers’ packs, or change himself into a stump beside a muddy road and vanish when someone sits on him. He punishes injustice, rewards virtue, and hates misers. Because a princess once tricked him into counting beets while she ran off with a rival, he is still a bachelor.

On a sunny morning I climbed a ski trail that zigzagged up a forested mountainside. The trail crossed a steep slide with rounded sides and banked curves. It seemed a quick, if arduous, way to the mountain top. Watchfully, lest I be struck by a toboggan, I climbed for nearly an hour, almost grateful for the shade of snowladen evergreens.

At the lip of a level bench I looked backward. In Spindleruv Mlyn, tiny and far away, sleighs stood in a row by the hitching post near the river. Skiers plodded up the main street as children on sleds sped down. Sledgeloads of logs moved slowly along the river, destined for the chugging gang saw of a hungry little lumber mill.

Riding the Logs

There was a shout behind me; I leaped aside for three sliding logs; butt ends lashed to a sledge. Speed slackened here. Without thinking, I climbed aboard. Braced on a high-backed sled, steering with long handles, stood a woodsman, his eyes on the sunken ribbon of snow trail winding breathlessly down the mountain. He did not see me.

We gathered speed. I clung, scared now, to the bark of the limber, dragging end of the top log. We whisked through shade and sunshine, zipped past trees and under frozen boughs. Powdery snow stung my face. On sharp curves I was whipped through snowdrifts. We rose over humps; as sled and driver thudded to the trail again, my end of the logs sprang skyward. Soon the slope became gentler, our speed slower. We glided to a smooth halt at a loading platform by the town.

The woodsman leaped from his sled, brushing wind tears from his eyes. He turned, saw me, snow-covered, tottering unsteadily, and said things in Czech.

Ascent of Schneekoppe, or Snezka, was easier. By aerial railway I floated from Janske Lazne over the trees to a high mountain tableland where frosty inns rent skis for 20 cents a day.

Novices may progress, if they can, from rolling mountain meadows to steep, difficult slopes lined with brown-coned evergreens that bow like green-robed patriarchs with icicles on white beards.

A Cruise in a Disappearing River

From the Krkonose I went south by train across the continental divide to Brno, second city in Czechoslovakia, capital of Moravia, and then to Blansko and the nearby Macocha Caverns.

Water, seeping through the limestone ceiling of a cavern in the Moravian Karst, remains liquid even in winter because of the warmth of the earth. Falling in drops, the water chills in the cold air, then freezes as it strikes the ground, slowly building up stalagmites of ice that will melt before summer.

Like something Poe had imagined, Macocha Abyss, some 400 feet deep, is a dread sinkhole in the forest, shaped like an hourglass. For centuries it defied descent. At its bottom is a sandy meadow with two little lakes. The Punkva, a disappearing river, roars into one, flows gently to the other; then it vanishes, gurgling.

From a nearby canyon we entered tunnels blasted by dynamite. On the surface above us were the forests, farms, and icy ponds of that snowy, long inhabited, rugged limestone plateau, the Moravian Karst. There prehistoric man had trapped and cooled the woolly mammoth.

The enchanted caverns through which we were clambering could have been a buried castle, complete with noble halls and dismal dungeons. Translucent stalactites, long, slender as pencils, curtained some sparkling chambers. In others were tiny pools, fountains, and rivulets where albino crawfish have lost the sight they no longer need. Water, dripping from one cavern entrance, formed no icicles overhead; a forest of ice stalagmites grew upward from the floor.

At last we crossed the bottom of the abyss, entered another tunnel, and reached the Punkva River where it surges upward beside a nether-world mountain. There we boarded a boat, the Styx. Sometimes we paddled, sometimes we pushed against stalagmites. Below us, frigid water was 60 feet deep. Suddenly, with an oar, the boatman threw an electric switch. Lights beneath the green water illumined it so brilliantly that the river seemed to glow.

At last, through misty spray, we saw a waterfall by torchlight, crashing down the cavern wall. In some leafy hollow, hidden in the forest above, an ice-covered stream had vanished, and here had joined its river. Through the Svitava, Morava, and the Danube it would reach the Black Sea.

There came a dull dawn as the buried river bore us onward; we emerged through a low, narrow cleft from a wide-mouthed cavern facing a mountain valley. To a miniature dock we tied the Styx.

Down the frozen valley, over its stony bed, the Punkva raced happily, its gloomy, subterranean journey ended. At Skalni Mlyn, a tavern by an old water mill, I ate thin, hot pancakes and jam with one of the engineers who, in 1933, had helped to open the Punkva to “navigation.” I asked him why the river was so long unknown.

Lowering an Underground Stream

“There are so many ‘siphons,'” he said, “that, until we lowered the river, no boat could enter. In 1747, Emperor Franz I of Austria, husband of Maria Theresa, sent Nagel, his court mathematician, to explore these caves. Nagel fixed a lighted candle to the tail of a goose and sent it hissing off into the darkness; he discovered little.”

“Dr. Karl Absolon, college professor, lowered himself into the Abyss of Macocha, and I explored the river in a deep-sea diving suit. With its underground course charted, we drove an aqueduct through solid rock for a third of a mile to drain off water from the river, lower it, and make it navigable.”

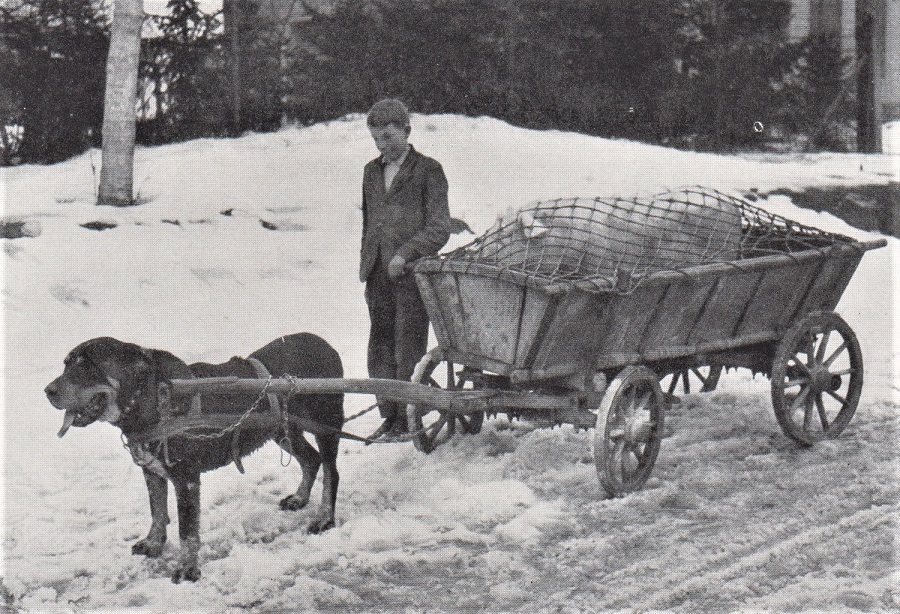

Back to Brno, we drove down the valleys of little rivers, across snowy, wooded hills. We passed countrywomen returning from the forests with loads of dry fagots that dwarfed them. One little boy drove a dogcart loaded with a big sow.

The little wagon, strongly constructed, will carry a hog weighing several hundred pounds. A rope net keeps the porker from jumping out. On uphill roads in the region of Slavkov, Czech name for the scene of Napoleon’s victory, the boy pulls beside his dog. Snow is deep, the work is hard. Both were glad of a rest on this dark winter day.

We paused at Austerlitz, now called Slavkov, scene of one of Napoleon’s greatest victories. “We still find relics here,” a farmer said. “Plows turn up teeth, bits of bone, and buttons from uniforms. Sometimes there is even a crucifix or a little shoe from a Russian pony.”

Gypsy villages are common in this region. Near Brno I saw an abandoned clay pit where a hundred Gypsies live in a score of one-room huts. In almost every tiny home someone lay sick. Birth rate and death rate alike are high.

Gypsies Have No Words for Many Bible Terms or for Time

In Brno there lives a professor whose hobby is little-known languages. He had been translating the Acts of the Apostles into the Romany tongue.

“Trying to translate ‘Savior,'” the linguist told me, “I found no Gypsy word for ‘save’ or ‘help.’ So, I call Jesus Sastipnaskro, ‘the Healthgiver.’ ‘Sincerity’ and ‘simplicity’ cannot be translated literally; I use ‘open heart’ and ‘childlike heart.'”

“Gypsies are easterners, without words for time. It means nothing to them. There’s no word for ‘straight’ and none for ‘honest.’ Something bright and new they cannot call ‘clean’; it is simply ‘beautiful.’ ”Words of possession and the verb ‘to have’ in all its forms are missing. If a Gypsy steals something, he never calls it ‘his.’ It has simply existed; someone else was using it. Now he has it.”

The linguist gave me the address in Brno of a place called ”Ivka,” where a Czech graduate of Vassar conducted an English conversation club. Ivka, I discovered, was the Czech pronunciation of “Y.W.C.A.” The clerk, observing that I spoke no Czech, said in simple German that the Vassar alumna was attending a lecture. It was nearly over; I might wait.

I wandered into the lecture room and sat down just as a movie flickered to an end and lights revealed a little audience of women. When the lecturer saw me, she scolded sharply in Czech. The audience looked annoyed. A young woman approached me and explained in English that this had been an intimate lecture, ”for women only.”

Later, she became my interpreter. We climbed snowy streets to the high fortress of Spilberk and looked upon the chimneys of textile mills that employ so many of the population. Below us was the University, established in 1919 and named for Masaryk. There, too, was the Supreme Court of Czechoslovakia.

Dr. Absolon, who made the Punkva a wonder of Europe, maintains a library, laboratory, and office in a moldy old building facing Kraut Market, a medieval square of Brno. When we found him, he was measuring with calipers the skull of a mammoth hunter in a musty room piled high with bones, papers, and fallen plaster.

In the Middle Ages despotic rulers employed many ingenious implements to force secrets from unwilling lips. In Spilberk Castle in Brno, now a military post of the Czechoslovak Army, torture chambers occupied dungeon rooms built in a disused moat. Today a wooden dummy (held up by a temporary crosspiece) demonstrates a rack that was found there, long ago. The prisoner’s wrists were bound to an upper rung. A rope, tied to his shackled feet, was attached to a powerful windlass by which the victim could be stretched until his joints were pulled apart.

“I’m busy,” he growled. “Why can’t people let me alone? Go see my museum!”

We did, at the Brno fairgrounds, though it took special permission to enter in winter. Moravian caverns were such excellent home sites for cave dwellers that excavations in their earthen floors have revealed changing artifacts of many different ages of humanity.

Some domestic and hunting scenes have been reconstructed in the museum. One hairy family sits about a fire in which mammoth bones ooze marrow juice.

Small sinkholes in the Moravian Karst provided means for weaponless man to gain food in the dim beginnings of his life in Central Europe. He covered the holes with saplings, twigs, earth, and grass; the giant woolly elephants fell through. Then he crushed their skulls by dropping rocks on them.

“We know that,” said Dr. Absolon, later, “because most skulls we find are smashed as only a rock could do it.”

And “Swing” was Born!

“Here, I believe,” the scientist said, “are the oldest musical instruments in existence.” From a cigar box he brought seven or eight little bones, wrapped in velvet, averaging the size of a chicken drumstick. Each was broken off at a different length.

He laid them in a row on his desk. Then he picked them up, one at a time, and blew into them like whistles. His hands moved faster and faster as he laid down one bone and took up another. At last he was playing a wild and savage tune.

“Perhaps tens of thousands of years ago, long before history’s dawn, some cave man with a strange sense of music played these instruments, as fur-clad hunters crouched by a fire, listening. Old at last, or more likely wounded and dying, he laid them by, and I found them.”

From a dusty window I gazed down upon the Kraut Market, now a tiny city with streets, alleys, policemen, and hundreds of little “stores” that literally would fold by mid-afternoon and leave the vast square to vagrant snowflakes, lone pedestrians, winter dusk, and the rubbish man.

When the Moravian opera singer returns to her home town, she visits her music-loving sisters, whose spacious, balconied apartment overlooks the public square. By mid-afternoon all evidence of commercial activity disappears, and the market, swept clean, becomes a promenade.

Ice Dumped, Like Coal, Into Cellars

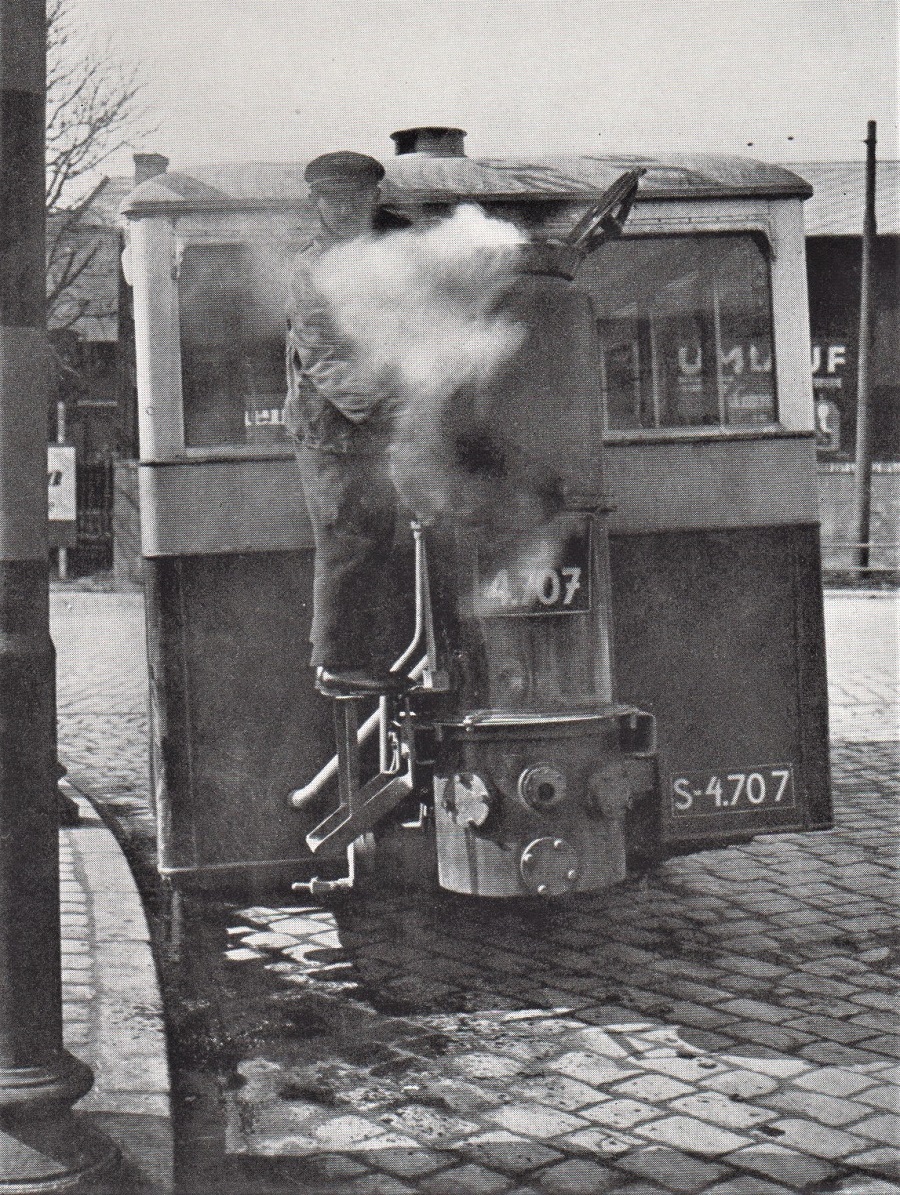

Horse-drawn wagons, piled high with river and pond ice, halted at one side of the square to dump their loads through chutes into municipal ice cellars beneath the Kraut Market.

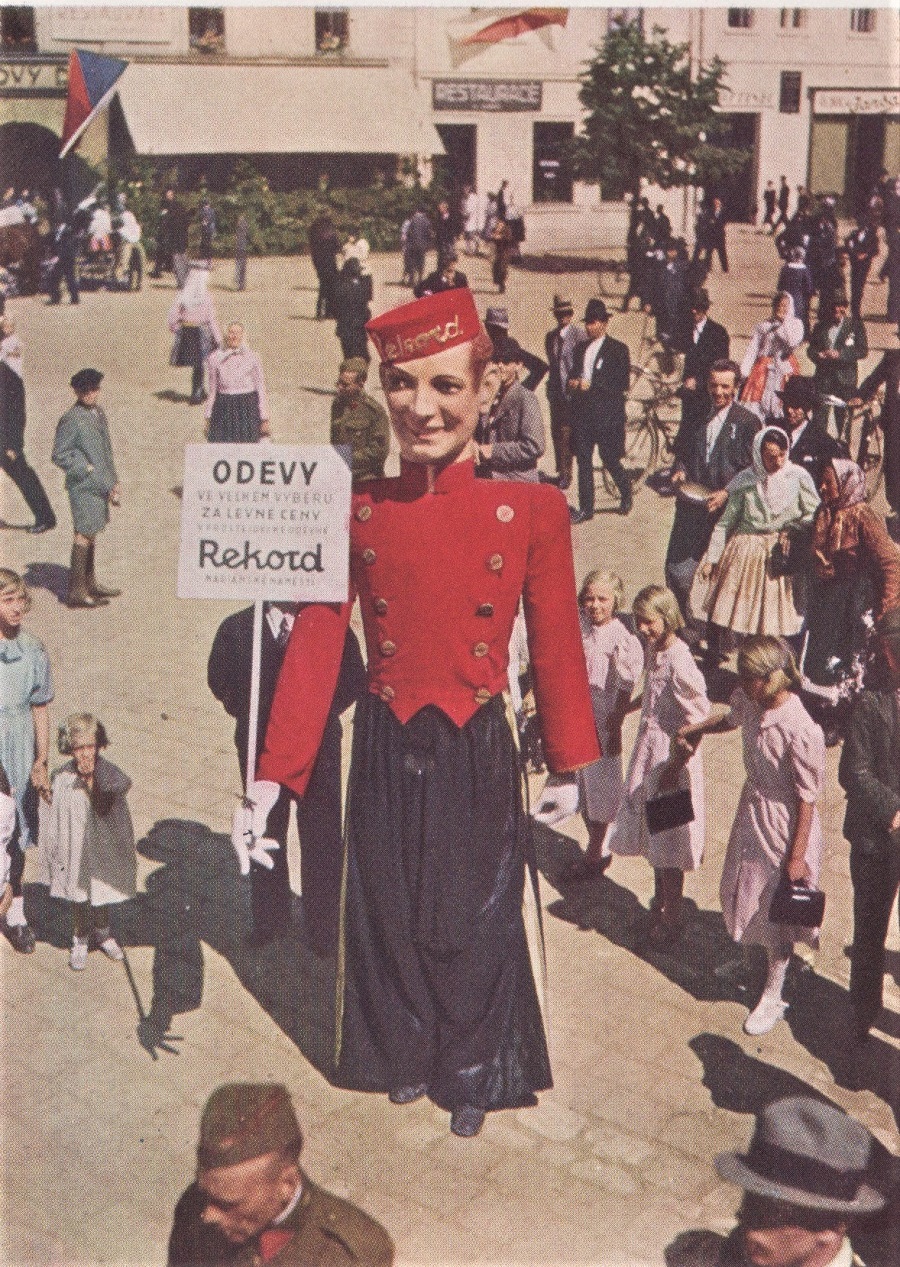

“Many styles, at the Rekord Store”, reads a sign carried in Uherske Hradiste. Beneath the papier-mache face and stuffed shirt walks a man all children envy.

Ice harvesting is a big winter industry in Czechoslovakia, despite increasing use of American mechanical refrigerators. Broken ice is dumped like coal into householders’ cellars.

“On warm evenings, when I was a student,” remarked Dr. Absolon, looking out of the window, “I used sometimes to see a little girl playing in the square. Often, she sat by the monument and sang to her dolls. She was a pretty child; her voice was sweet. Once in a while I wished that she were grown up, walking with me. Years later, she became a famous singer.”

“What was her name?”

“Jedlicka. The family lives across the square.”

“Jedlicka?”

“Maria Jeritza, now.”

At the Jedlicka apartment, that afternoon, Jeritza’s older sister invited us in. The largest grand piano I had ever seen dwarfed the massive, hand-carved furniture of the big room. Near it hung Jeritza’s portrait, lifelike and beautiful. There had long been singing in this room. Jeritza’s sisters,who look Iike her, sing here still.

“Isn’t that Jeritza’s daughter?” I asked, observing a photograph of the opera star with a young girl. “There’s a strong resemblance.”

“That’s my daughter!” replied our hostess, proudly. “We all look a little alike. She’s in Hollywood now, with Maria, studying. We think she’ll be a success.”

Mendel Worked in a Monastery

In Brno, where the strange problems of heredity puzzled Johann Gregor Mendel, an Augustinian monk, I saw his laboratory, his microscopes, and old foolscap pages filled with calculations based on his experiments with hybrid peas. His conclusions are known today as “Mendel’s law.” Although the scientist died more than 50 years ago, his thermometer remains where he fastened it, outside his study window in the monastery.

The instrument stood just at freezing as I walked down the brick path that ran beside his long, narrow garden. Monastery walls shaded it from the afternoon light. Now, through a half inch of snow that lay upon it, a few pansies thrust their determined way.

“We planted sweet peas here, as Mendel did,” said the monk who guided me, “but we can’t make them grow.”

On a spring like March morning snow was melting as I rode southward from Brno on a high-speed streamlined train to Bratislava.

Once this port on the Danube served as capital of Hungary; now it is the rapidly growing provincial capital of Slovakia. Czechs, Slovaks, Jews, Germans and Hungarians tread old cobblestones of St. Michael’s Street, dodging buses that burn charcoal instead of gasoline. If they break the laws and go to jail, it is to a modern building built partly of glass bricks. If they need medicine, they may seek out the Sign of the Red Scorpion, where an apothecary shop just beyond St. Michael’s gateway has been operating continuously since 1310.

Despite the rapid growth and progress of that city, much is unchanged. A few people still live in cubbyhole cellars under Castle Hill.

A drugstore, founded in 1310, still operates at the Sign of the Red Scorpion. Some drugs used in prescriptions today are kept in jars bought when the store was young.

Fuel is poured into a rear tank, and a fire built underneath. Then the lid is clamped down, depriving the fire draft and preventing complete combustion. Unburned gas, passing through the filters to remove charcoal dust, is drawn by a supercharger into an automobile engine. The gas explodes much like gasoline vapor. Knocking and slow pickup result, but operating costs are low.

East of Bratislava is the valley of the Vah. First broad and fertile, it narrows between Carpathian ridges as the swift river flows past isolated, lofty crags where medieval castles show jagged lines of broken battlements against the sky (Plate XIV).

This ruin in Lietava, near Zilina, on a tributary of the river. Slovak peasants, driving to market in their oxcarts through fertile mountain valleys, tell their children of the prankster Janosik, legendary hero of the region, who robbed landed nobility and fed the poor.Once, when a gentlefolk had assembled for a castle banquet, the robber knight arrived with his band, pretending to be strolling players with a drama about Janosik in their repertoire. As their realistic acting was enthralling guests, bandits and village folk quietly ate the feast.

In one such ruin in the wooded Carpathian Mountains, above a valley farmed by Czechs and Slovaks, the opening scenes of the weird novel Dracula were laid. Bram Stoker based his story upon superstitions of the country folk that long-dead masters of some old castles returned by night as vampires to prey upon the living.

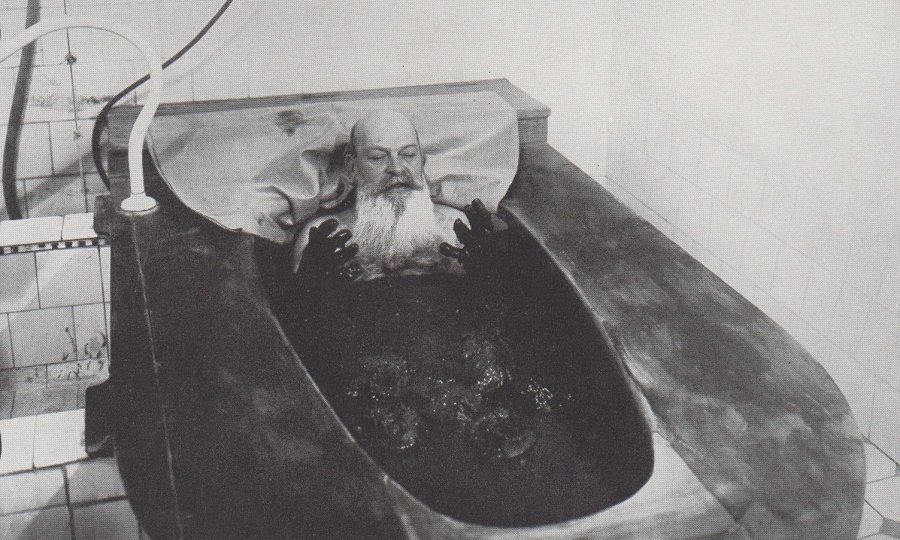

Trademark of Piest’any Spa is a bronzed athlete with bulging biceps, breaking a crutch over his bent knee. I went there for a bath in black volcanic mud.

So they say in Piest’any, where hot volcanic ooze is scooped from the bottom of a cold river. The author took such a bath. After a playful, perspiring half hour in the slippery mud, it was troweled over him thoroughly. Then, shrouded in oilcloth and sheets, he was put on a shell to cool gradually before a shower and a rubdown completed his “rejuvenation”.

In its largest hotel I rented a royally furnished room that had once been occupied by Wilhelm Hohenzollern, German emperor.

My balcony overlooked a foggy valley and the swollen, ice-choked Vah. On a clear day, they said, I could see the castle where Elizabeth Bathory, in search of her youth, had murdered scores of young women centuries ago to bathe in their blood.

In a fast, air-cooled, rear-engined Tatra car, made in Czechoslovakia, a friendly Chicago Czech took me from the spa, Trencianske Teplice, to Trencin.

There we saw an inscription, chiseled into the base of a cliff, describing ancient Roman occupation.

High above it, long impregnable, but ruined now, Trencin Castle frowns over the valley it guarded so long. Six hundred years ago, when the castle was already old, its bold owner seized and ruled all Slovakia and part of Moravia.

We climbed upward through melting snow and muddy rivulets. Within the outer walls, below the castle, is a windowless dungeon. Through a small hole in the roof, a culprit condemned to more than the swift flash of the headsman’s ax he begged for, was lowered, with a loaf of bread and a jug of water. Then this single aperture was bricked shut.

We were shown a broad, deep well. “Once,” the guide related, “the lord of Trencin, fighting the Turks, captured and brought a girl here. Her Turkish sweetheart, with a few retainers, came under a flag of truce to buy her release.”

“‘We’ll keep her,’ said the lord, ‘until you get water from this rock!'”

“Taking the discouraging refusal literally, the Turk bought rock drills and with his followers began a well. After seven years he struck water at some 200 feet; and the lord of Trencin kept his promise.”

A Czechoslovak National Park

Still following the Vah, I continued next day to Zilina, then eastward, watching the floe-filled raging river as it piled pieces of its winter prison high against trees and fences. Late at night, in the rain, I changed from train to bus at Strba.

At this gateway to the Czechoslovak National Park, the High Tatras (Tatry) rise sharply from the plain, like the Grand Tetons in Wyoming, through fir and beech forests, stunted spruce, alpine meadows, and barren rock-strewn slopes, to the snow fields at their crests.

Lynx and bear are almost wiped out; chamois and eagle share the solitude beside sixscore mountain lakes.

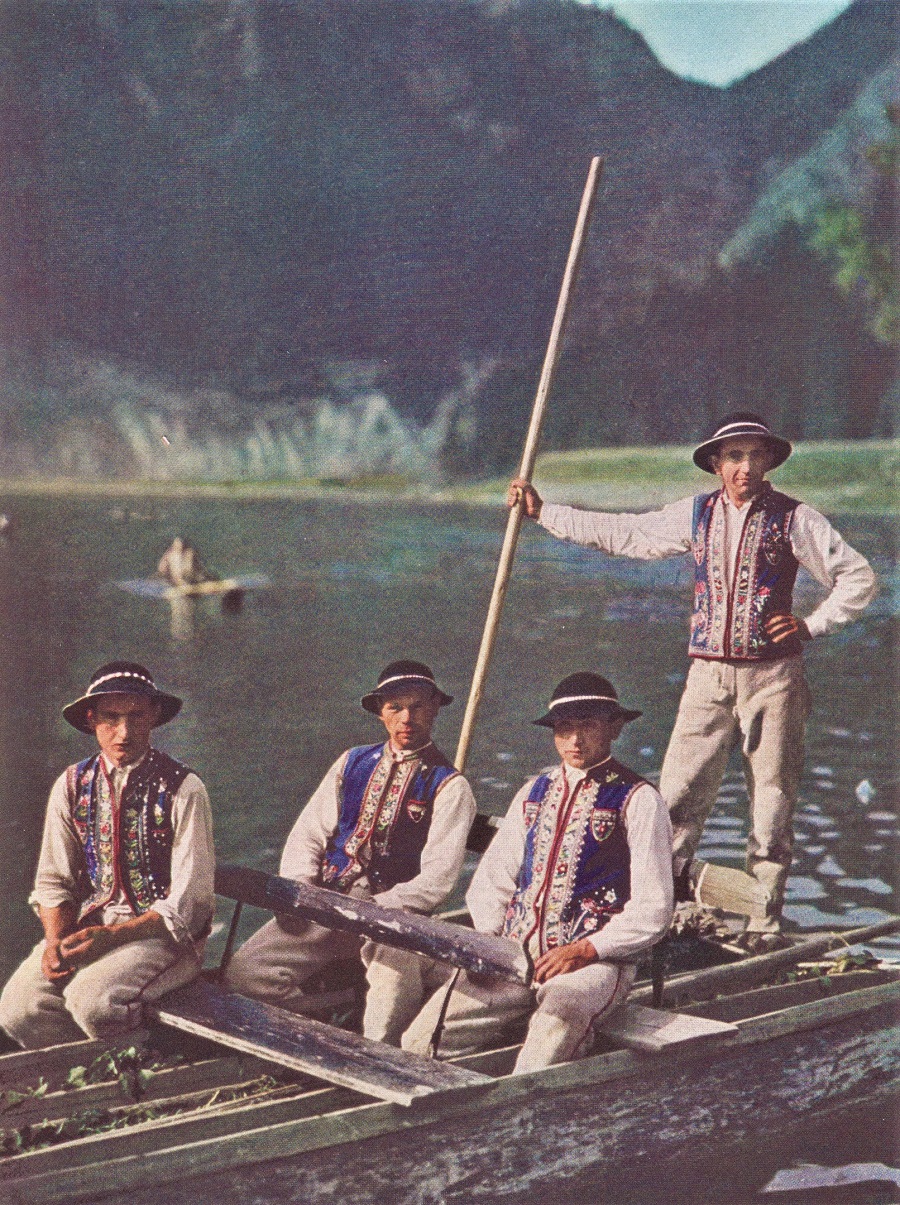

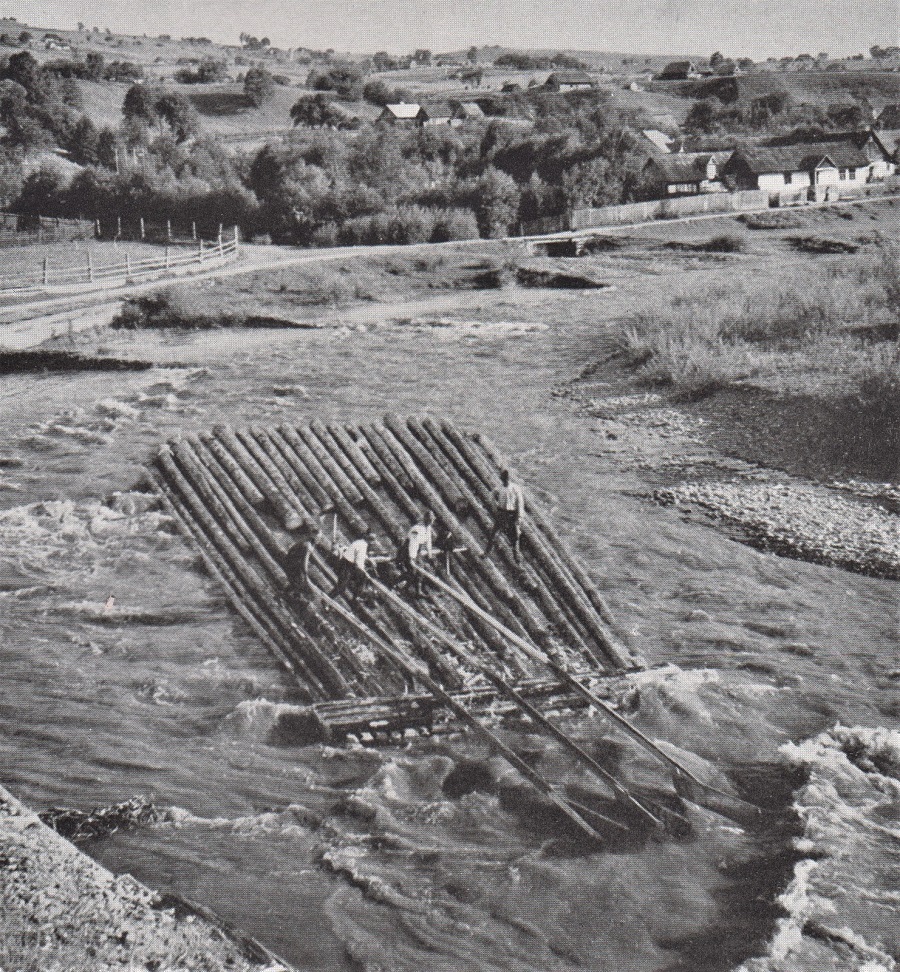

Most of the long, ragged border between Czechoslovakia and Poland is a mountain divide. Here, northeast of the High Tatras, the frontier is the Dunajec River, much used for floating Jogs to market. Poles and Slovaks, in the costume of their calling, carry international passengers for a few coppers in their catamaran dugouts. Farmers of the neighborhood, who often own land in both countries, carry simple identification cards and may cross the border at will.

The bus to Strbske Pleso climbed slowly for miles through the forest, then broke through the frozen crust of the snow that covered the twisting mountain road. For two hours we waited, stalled. Air became colder as night wore on, and rain turned to snow.

At last, muffled by thick-falling flakes, sleigh bells echoed cheerily down the mountain. Wrapped in fur robes, bus passengers were bundled into a two-horse open sleigh. Upward through the night we rode and tinkled to a halt in a blaze of light from a mountain hotel.

By rainy daylight the inn looked forlorn beside its misty lake. Trails became slush; thick fog hid the mountains. I departed by electric train, skirting the Tatra slopes past Stary Smokovec. We waited in one village while an ice jam was broken by firemen with pike poles.

Half an hour before this photograph was taken, huge blocks wedged tightly against a railroad bridge near Poprad. Housewives worked frantically, building mud dams higher and higher in their doorways to keep out rising water. Setting to swiftly work with axes, picks, and pike poles, helmeted firemen and their helpers soon loosened the jam, and now the water recedes. An instant later, the bog cake to the right broke away. Three of four occupants, leaped to safety. One was carried under the bridge and downstream toward the Vah River. He was soon able to grasp an overhanging tree limb and scramble ashore.

Uzhorod, east of Kosice, on a branch line of the railway north of Cop, is the capital of Ruthenia. Officially called Podkarpatska Rus, or Sub-Carpathian Russia, it is the smallest, most primitive, least inhabited of the four provinces.

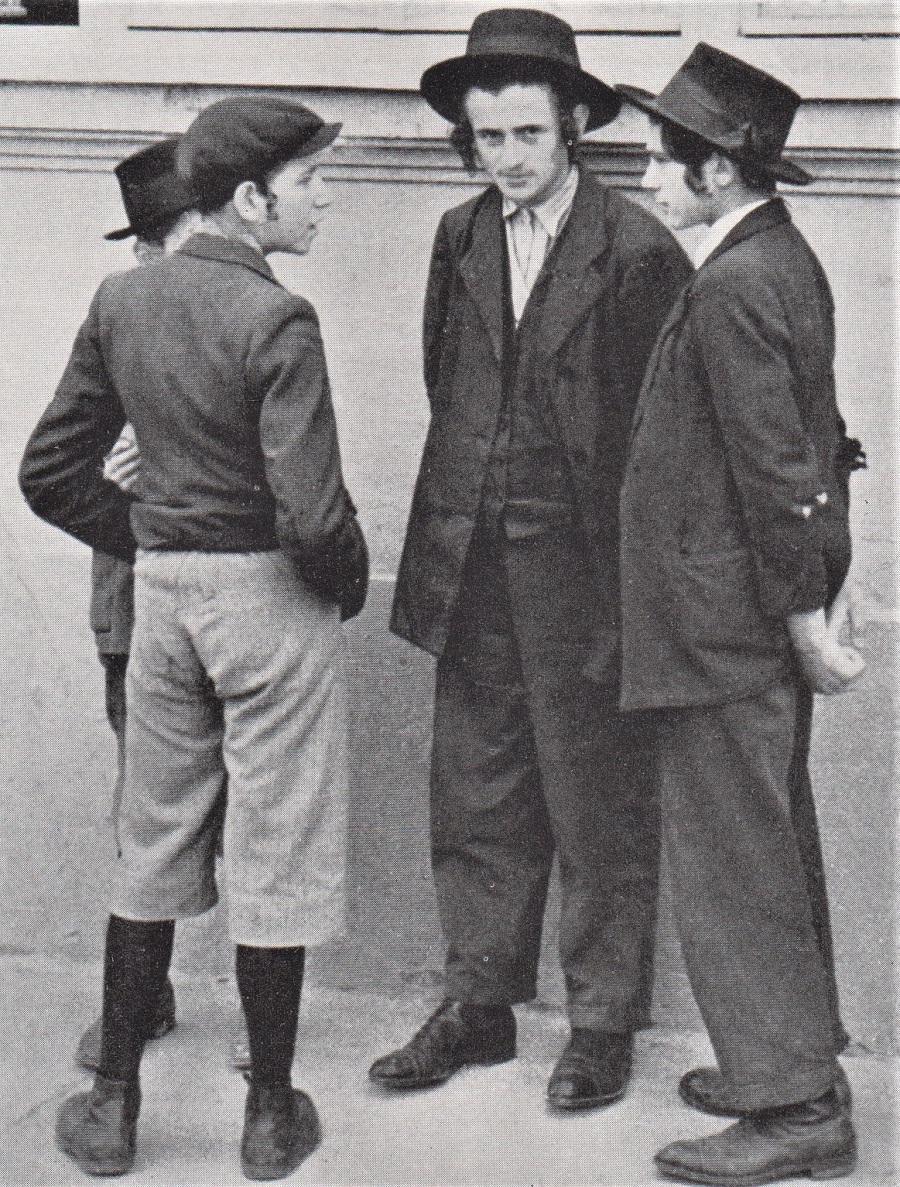

A medley of people’s lives peaceably in Uzhorod. Sturdy Little Russians are tough as their wiry ponies. There are Jews who dress in funereal gabardine and wear curls for sideburns.

Like other peoples in far-eastern Czechoslovakia, Jewish inhabitants cling to the ways of their fathers, who wear black gabardine, and usually beards. Entering a synagogue one cold day to listen to the cantor, the author automatically removed his hat, and was reminded that the custom was to wear it.

Industrious Poles have come from the north. There are German businessmen and carefree Gypsies. There are handsome Hungarians who remain despite the new regime, and ambitious Czechs and Slovaks who have come because of it. There is a sprinkling of other races. A young Gypsy was buying a new violin, for about a dollar, from a storekeeper who spoke his Romany tongue.

“I sell goods,” the merchant said to me, “in eight languages.”

Between Cop and Jasina, Czechoslovak trains “go abroad” for a few miles. At Sighet, in Romania, I took an international local to a Ruthenian salt-mining town.

Business as well as sentiment lay behind the preservation of local traditions in Cicmany. While the men, in their fancy shirts are lumbering or farming, the women sell blouses, tablecloths, and other fancywork to visitors. House decorations are similar to the cross-stitch designs.

White sand, poured in a tiny stream from a hole in a bag, is used to design a carpet for a wedding procession on the Moravian road to matrimony. No cleaning will be required afterward when traffic is resumed on the damp earthen street, for the sand will be scattered and the pattern obliterated.

Breathless Grandeur of a Salt Mine

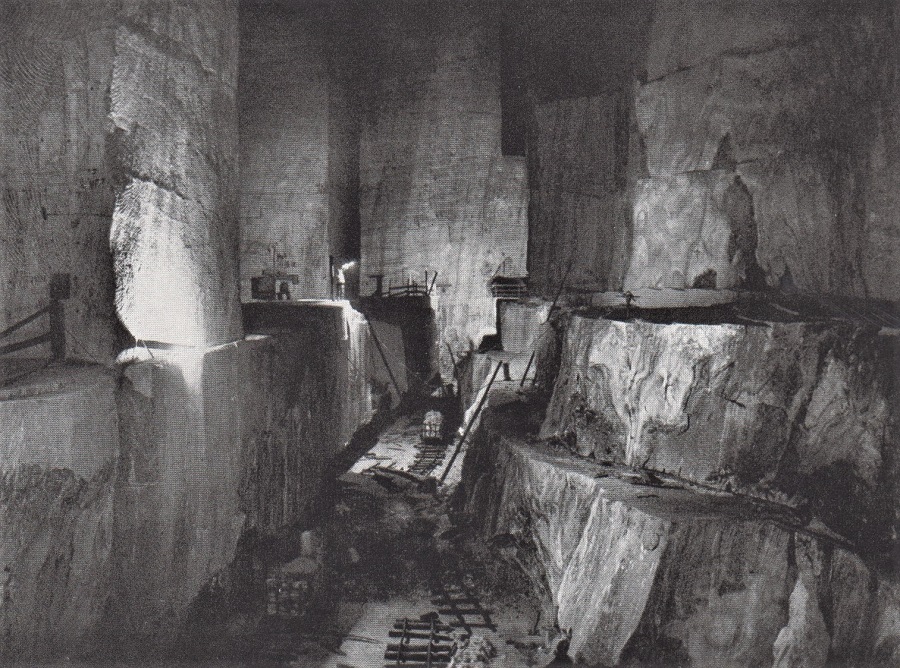

If the Great Salt Lake were poured into Jacksons Hole, Wyoming, evaporated, and slid under the next county; if a shaft with a fast elevator were sun]( through solid salt; and if, since 1777, men had carved crystal columns, vaulted roofs, nave, transept, chapels, and cloister garth, the breathless grandeur of that subterranean cathedral would be the prospect of the excavated stopes of the salt mine at Slatinske Doly.

On a little wooden catwalk anchored to the roof, I stood with the chief engineer. Below us yawned a gulf so profound that workers loading salt blocks looked as small as mice.

The torchbearer seems insignificant, on a ledge in the left center. A mining engineer at Slatinske Doly estimated that if the enormous Cathedral of St. Vitus were placed on the floor of the room, its tower tips would lack 30 feet of reaching the roof.

Crystalline walls reflected twinkling lights. Around us, like the roar of a far-off waterfall, rumbled the echoes of pneumatic chisels, cutting this titanic temple vaster still.

At the end of the Ruthenian tail, a few minutes by train from Poland and farther east than Greece, lies Jasina.

Members of one political party, parading in Uherske Hradiste, carry pork-on-sabers, often used as wedding gift symbols. These campaigners hope really to “bring home the bacon” on election day.

After standing reverently in their picture-adorned temples during the long Mass, the pious pause in the Jasina churchyard to say prayers, or to place flowers on the Crucifix. Huculs are strong, tall, and highly intelligent, despite the rude simplicity of their lives. Though they are Ruthenes, they are proud of their Russian origin and language, and avoid intermarriage with other races so numerous in Ruthenia. Hemmed in by barriers of Carpathian mountains, this little-known tribe has maintained the purity of its blood, and its racial character for uncounted generations.

Unpainted wooden churches of the Huculs in Ruthenia contain no seats. This one, near Jasina, appears weather-beaten and austere to the traveler; inside, it is lavishly decorated and hung with sacred paintings.

Most Hucul folk here live in floorless mud cottages without chimneys.

Smoke from wood stoves, escaping though the roofs, seeps between shingles and through attic ventilators, giving the log cottages of Zdiar a “house afire” look on winter days. The friendly villager, with the pipe, left the photographer to a shepherds’ camp in the distant hills, where sheep milk is made into huge cheeses. Hospitably, the herders led their visitors – on sheep cheese, curds, and whey.

Smoke filters through the thatched roofs, making them appear to be burning.

At the eastern tip of Czechoslovakian folk dress shows few signs of vanishing. Factory shoes compete with pointed moccasins, made of one piece of leather and tied to the feet with things.

After the breakup of a parade in Jasina, participants pause to chat. There has been a shower; some still carry umbrellas and wear their coats inside out. High-heeled slippers contrast with the rest of the apparel of the women at the right, and with the pointed moccasins of her companion. Immediately after the World War, America sent food to the starving Ruthenes. “I helped distribute it,” a woman said. “We gave them cocoa. They didn’t know it was food. We found them mixing it with water to paint base around their whitewashed houses.”

Here Bata sells few shoes; farmers and herdsmen prefer to tie soft, thick leather around each foot.

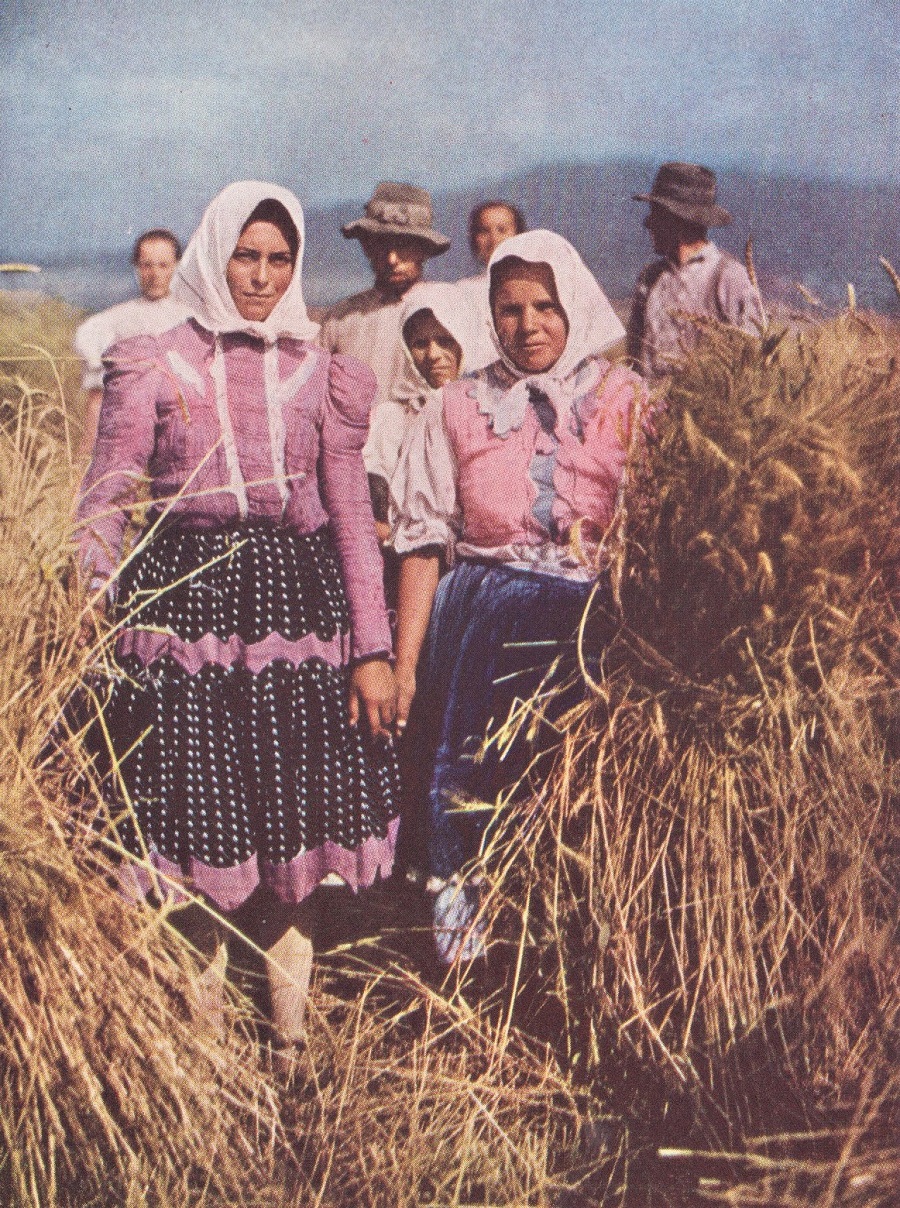

Gleaners, gathering loose and scattered stalks of wheat in their aprons, rarely miss a single ear. Even gypsies may be found working on this tenant-operated Kosice farm, once an old Hungarian estate.

Snow still lay deep, for winters are cold and long. Logs skidded down icy slides from the mountain slopes. Some were being ripped into lumber, as I have seen it done in China, by one man standing beneath, and another, above, dragging a handsaw. Some logs would be rafted down the Tisa after the ice went out (page 211).

Though lumber is still sometimes sawed by hand in the mountains of eastern Czechoslovakia, much timber is assembled in rafts and floated down the Bila Tisa River to steam sawmills. Where the stream is narrow and twisting, with gravel bars and jetties, the trip is exciting and dangerous.

Oxen hauled other sledge loads to an anachronistic steam sawmill that could saw more lumber in a day than a hundred men.

One old-timer said it “threw too many men out of work”; he hoped it would burn.

Sleeping in a Haunted Castle

From frozen Carpathians I returned to Bohemia. An old ambition was to be gratified: after weeks of trying, I had obtained permission to sleep in a haunted castle, alone in all its 70 rooms except for one lady, Perchta von Rosenberg.

A sudden spring rain welcomed me to Trebon, a town still so medieval that all its entrances are through long arches at street level, under tall, thick-walled “gateway” buildings. Trebon Castle, dominating the town today, is partly modernized and is occupied by its owner only in the summer. It was held by the Rosenberg family until Petr Vok, last of his line, died in 1611. Finally, it passed to the Schwarzenbergs.

Strange beliefs persist, as they do in the Carpathians, among country folk who live among moors and fens of this land of lakes. To thwart ghouls, they say, Schwarzenbergs are buried at night, in secret. “I’ve heard of a big cellar,” one farmer told me, “where dead Schwarzenbergs sit around a long table, like a family reunion in life.”

There is a legend of the White Lady, Perchta von Rosenberg, whose deep love for a family enemy caused her death in 1468. For more than a century the White Lady stalked labyrinthine castle corridors so quietly that she disturbed no one. When Petr Vok lay ill and dying, she is said to have come out of the shadows to nurse the last Rosenberg.

“You will sleep,” a caretaker told me, “where the White Lady slept five centuries ago. She has often been seen there. No harm comes if she wears white gloves. But if her gloves are black, beware!”

He led me by lanternlight through the rain, across a wet courtyard where leafless trees howled in the night wind. He pushed a giant key into a ponderous old lock; there was a click like a hammer on iron, and he swung open a timbered door that rasped on its hinges.

Our footsteps sounded hollow and sepulchral on the flagstone floor. The air was cold and clammy; spring warmth had not yet penetrated this chill pile of stone. My room was warm. A fire had been burning for days in a blue-tile stove shaped like a giant stocking cap, tassel and all. Furniture was old and blue, like curtains, bedspread, and the flowers on the washbowl.

The caretaker showed me how to bolt the door and departed. His bunch of iron keys tinkled out of hearing. Through the rain-blurred windowpane, I saw his light, bobbing across the courtyard and down the lane. For added cheerfulness I lighted a candle beside the four-poster bed, turned down the royally crested sheets, and examined my room.

Hidden Knob to a Secret Door

Its strong bolts reassured me. Then I studied a strange wallpaper design and felt its velvety texture. My hand ran over a hidden knob, and before me opened a door into a chill room that was quite bare. Other passages, and perhaps other secret doors, led from it. Fearfully I braced an armchair against that mysterious portal.

Apprehensive, I left my bedside candle burning. My head sank so deeply into the soft, thick pillows that I could not see the candle flame, only its light on the wall. I closed my eyes for a moment, then opened them, lingering in a halfway station on the road to sleep.

But I was asleep, dreaming horribly. A gigantic black vampire, big as a man, whipped across the room; then, as sinister and silent as Count Dracula himself, it swept back again. I had half expected to see the White Lady, but I had not been warned of this dark flying phantom. I slid under the covers of the big bed.

When I awakened, sunlight was streaming in. I sat up and looked about. Beside the extinguished candle lay a giant moth, burned to death. I had seen its shadow on the wall as it flew around the candle.

I went back to Praha for an appointment, arranged days ahead, with Dr. Eduard Benes, President of Czechoslovakia. The intervening time was busy.

That night I registered, by leaving my passport for the police, in a weather-beaten old hotel near the station, planning to seek better quarters next day. I was astonished to find thick carpets, new furnishings, soft mattress, hot and cold water, plenty of lights. A thick feather bed served for quilts. Reading lamp, easy chair, desk, and lounge were made of tubular chromium-plated steel. Across the hall was a clean, modern shower bath.

Beside the hotel a cleaning and pressing shop used American-type equipment, but was unaccustomed to pressing coat sleeves. I found one automat cafeteria where the coffee was even better than in fashionable restaurants. The place I preferred was always crowded. Most items were a crown (three and a half cents). Oranges and grapefruit were squeezed without charge on a California-made electric juicer.

There are chain stores called ”fixed price” because there is no bargaining. Prices begin at half a crown, less than two cents. Arrangement and choice of merchandise reminded me of ten-cent stores at home.

At the Old Town Hall I studied coats of arms of medieval guilds: a bobbed haired girl is the barbers’ sign; and Adam and Eve the potters – because they, too, were clay. At the astronomical clock I watched the Twelve Apostles pass its windows as a skeleton tolled the time.

Built before America was discovered, the astronomical instrument on the Old Town Hall in Praha still ticks off months and minutes with fair accuracy. On the hour a cock crows; upper windows fly open; Christ and his Apostles file solemnly past. Figures beside the dials become animated: Vanity looks at his mirror and Avarice clutches a moneybag. Then Death, holding an hourglass tolls the passing of another 60 minutes. Old at last, and dying, the blind man was allowed to revisit the tower. With a sledgehammer he smashed the mechanism; for years it remained a wreck.

In Alchemists’ Street, or Golden Lane, I visited the tiniest houses in Praha, where art-loving, melancholy Rudolph II, short of money, hopefully provided shelter, crucibles, and scrap metal for medieval experimenters called alchemists.

Some old streets I saw, with heavy gates at their ends, were locked at night. The library of Strahov Monastery, old before Gutenberg printed books, contains many aged charts of the Kingdom of Bohemia.

Cartographic masterpiece was a leather globe, 12 or 14 feet in circumference. The shores of California, an island, were carefully indented with harbors that were named. Chesapeake Bay was marked “Cheesepiook Sinus.”

A Jewish guide took me to a medieval synagogue and Jewish cemetery. “My ancestors are here,” he said, placing a ritual pebble on a weathered tombstone.

“They lived in the Ghetto,” he continued, “when such names as Judah ben Abraham, meaning ‘Judah the son of Abraham,’ predominated. ‘Levi’ and ‘Katz’ meant priests. Cohens were ‘high priests.’ When it was decreed that Jews must have family names, priests used their titles. Others took names of noble protectors, like Schwarzenberg, Lichtenstein, or Rosenberg. Grafting officials charged high fees for pretty names such as Rosenblum, meaning ‘Bloom of the Rose,’ or ‘Perlmutter,’ ‘Mother of Pearl.’ Poor or stubborn people got uncomplimentary names.”

An Interview with Dr. Benes

Next day came my appointment with the Chief Executive. My taxi driver crossed Charles Bridge, drove up the hill of Hradcany and into the courtyard of the regal old Castle of Praha.

Long a leader in the fight for Czechoslovak independence, Thomas Garrigue Masaryk (1850-1937), for nearly 30 years university professor of philosophy at Praha, married an American girl. When the World War broke out, he fled to Paris, organized his exiled compatriots, and in 1918 came to America. He wrote Czechoslovakia’s Declaration of Independence in Washington, D. C., and became his country’s first President. Eduard Benes, his Foreign Minister, now is President.

When Dr. Benes rose from his desk to greet me, his laugh was deep and throaty, as if most of it remained inside. In the course of the interview, I mentioned that I had found in Czechoslovakia many rules making it excessively hard to start a new business or to engage in a new trade.

”Many laws, taxes, and regulations were imposed by our conquerors, and have been in effect for centuries,” the President replied.

“We are changing them as rapidly as we can. Masaryk said that no strong central government had ever succeeded; we are giving more home rule, not less, to political subdivisions. Recently we relinquished much federal control of schools. Our Supreme Court, divorced from politics, preserves our democracy.”

“Some writers,” I said, “fear that this Republic will fall apart. Your peoples are so diverse, – Czechs, Slovaks, Germans, Hungarians, Russians, Jews, Gypsies, and Poles. Slovakia and Bohemia are more different than some nations!”

Races Welded by National Unity

The President leaned over his desk, talking rapidly in English. “You found Moravia and Bohemia rather alike, didn’t you? Sixty years ago, Moravia was as different from Bohemia as Slovakia is now. In sixty years, more you won’t see much difference among the three. Czechs and Slovaks are racially the same people.

Remarked by the innkeepers daughter, who wears aprons all week, when she appeared in her holiday dress. The National Geographic photographer stayed at Ostrozska Nova Ves in the hotel of her father, who is a local leader of one of the many political organizations of democratic Czechoslovakia. This Sunday, his family and 300 followers in costume, he dressed up for a parade.

After many hours at her ironing board she goes, not to a dance, but to church. Her maidenly industry is admired by young men of Blatnice – but only from a distance, lest her hundred pleats be wrinkled. Citizens in democratic Czechoslovakia dress much like Americans, and even farm folk have given up traditional festival costumes in densely populated, industrialized Bohemia. In less urban Moravia, fuzzy jackets and bright-colored skirts, hand-worked collars, and starched, puffy sleeves are usual features of the holiday wardrobe of a countrywoman.

Not far away, on the Hill of Bradlo, is an imposing monument to the national hero, killed almost 20 years ago. The legions he commanded, units in the Allied armies, were made up of patriotic Czechs and Slovaks. Sweeping land-reform laws divided large estates of noblemen and made landowners of farmers who cultivate the narrow fields. Wheat, barley, and oats are ripening, almost ready for harvesters from Brezova, the village below.

In winter this pair lives in Vesli nad Moravou: in summertime they follow the festivals. When father squeezes the goatskin with his elbow, the big bass horn booms forth behind him. As he plays folk tunes with his fingers on the smaller horn, his daughter collects contributions.

People gather from miles around to the hill church of St. Anthony near Uherske Hradiste. Some walk; some come in wagons; others pedal bicycles – an amusing sight when riders are multi-petticoated girls who wear pleated skirts ballooning in the wind.

A matron rests on the way to Svaty Antonicek. The basket lunch may be supplemented by large, red, heart-shaped cookies or fresh cherries sold in the churchyard to pilgrims who picnic nearby.

So great are the summer crowds at the Shrine of St. Anthony (Svaty Antonicek) that many of the pious must worship out of doors. Collection boxes affixed to trees receive their offerings.

“Jews, free as in England or the United States, are no problem here. Every country in Europe has Gypsies. Poles are only one-half of one percent of our population. Little Russians joined us at their own request.

“The American problem is assimilation. Ours is not. We won’t attempt to make Czechs of our German millions, or Slovaks of our 700,000 Hungarians. Germans may remain Germans, and Hungarians may remain Hungarians always, with their own schools, languages, and newspapers, – free citizens of a democracy, enjoying equal rights with all of us.

“Austria tried for centuries to Germanize the Czechs and failed. Hungary sought for a thousand years to Magyarize the Slovaks, and failed, too. We won’t make their mistake!”

They Read What They Please

“Our people are educated. They read what they please and think deeply into political questions. They do not exist for their government; their government exists for them. We do not fear a demagogue here; no skillful spellbinder could last in politics – not in Czechoslovakia.”

John of Nepomuk was thrown to his death in the Vltava from Charles Bridge in Praha because he withheld from King Wenceslaus IV the confessions of his wife. The holy man is now patron saint of bridges. Each May 16, a pilgrimage is made to the spot where he was cast into the river and his statue now stands.

I was impressed by this man who had become one of the most remarkable of living statesmen, and by something else he said: “Czechoslovakia is a democracy, conscious that it stands in Central Europe like a lighthouse high on a cliff, with the waves crashing on it from all sides.”

And thus we conclude the post on Czech Yankees. Let us know your thoughts in the comment area below.

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Thank you in advance!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.