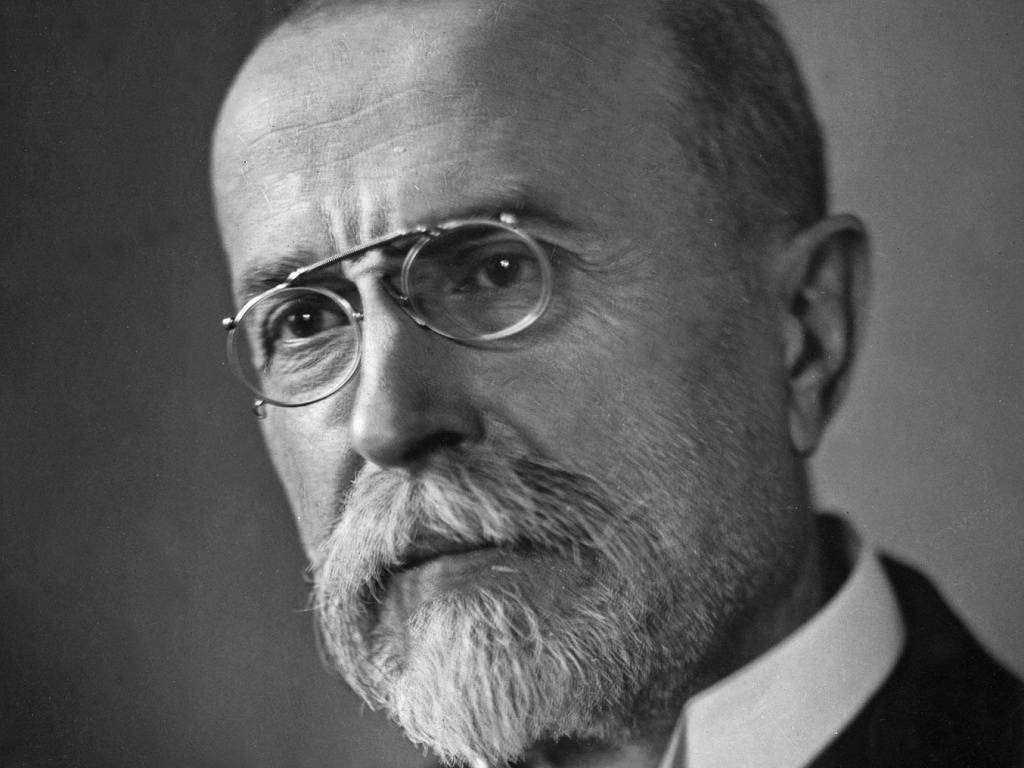

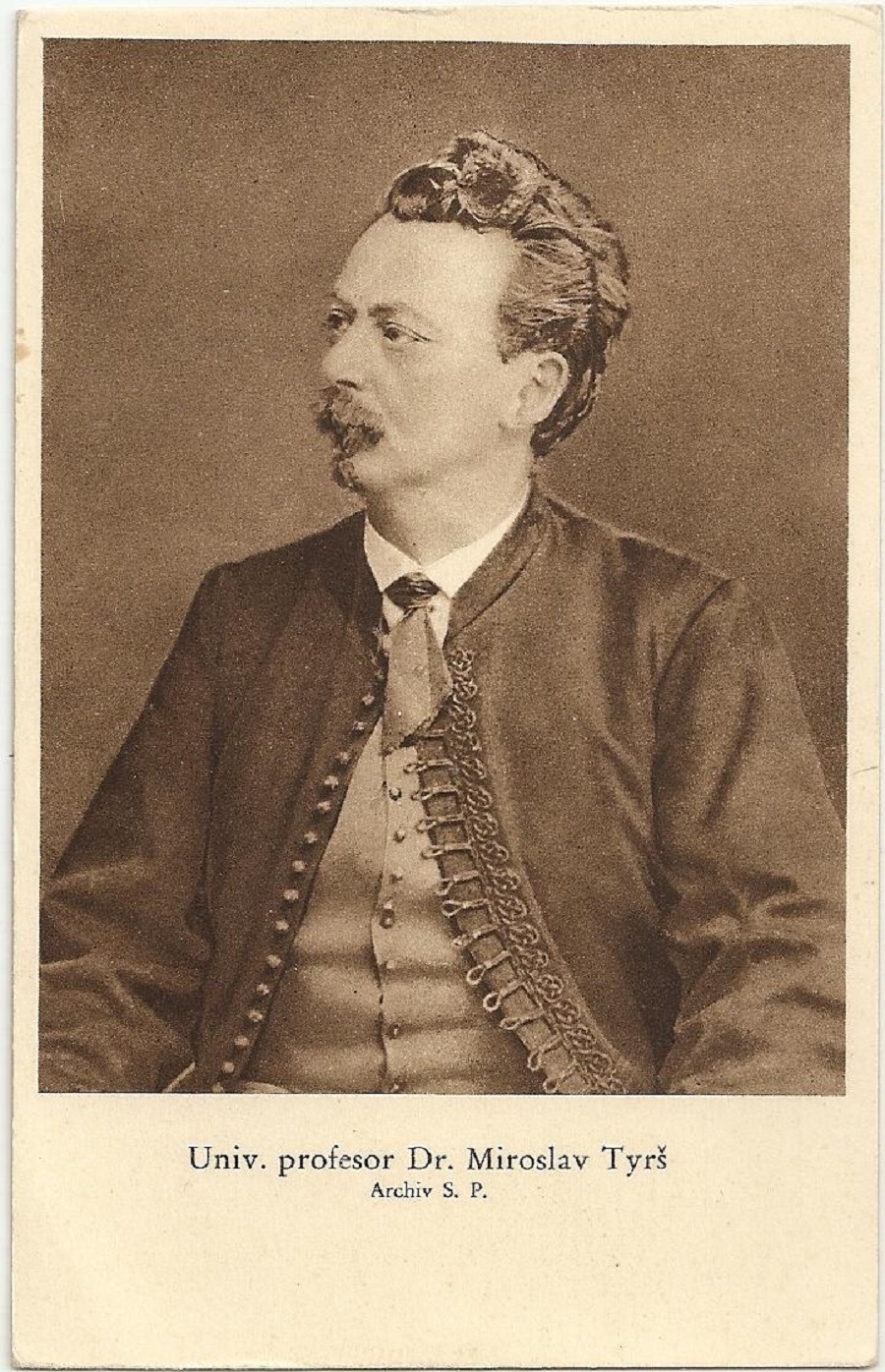

Let’s travel back in time, to 1920, and take a look at Dr. Miroslav Tyrš Founder of the Czech Sokol Union. Miroslav Tyrš was actually born as Friedrich Emanuel Tirsch on September 17, 1832 and died on August 8, 1884. He was a Czech art historian, sports organizer and as we’ll learn today, the founder of the Czech Sokol movement.

Miroslav Tyrš was born to a German doctor in Děčín. The family then relocated to Döbling near Vienna where both is parents and his two sisters died from tuberculosis. Tragically, this made him an orphan at the age of six years. As a result of the death of his family, he was raised by his Czech uncle in Kropáčova Vrutice near Mladá Boleslav and this is how he was assimilated into the Czech community.

He studied Gymnasium in Malá Strana, Prague and passed its final exam in 1850. At a time when all students were required to take their exams in the German language, Tyrš insisted on taking the exam in Czech to make a patriotic, pro-Czech stance.

As a 16-year-old boy, he fought in the streets of Prague during the Revolution of 1848, and then boasted of his shot-through cap. He also changed his Christian name twice, first to Bedřich (the Czech version of Friedrich) and then to a very Slavic name, Miroslav.

In 1860, he became doctor of philosophy with a thesis dealing with the philosophy of Arthur Schopenhauer. (See note at the end of this post.) He also contributed philosophical articles to the first Czech encyclopedia – Riegrův Slovník naučný. After failing to get an academic job, he left Prague to work as a tutor for sons of a businessman in Nový Jáchymov near Beroun. His own ill physical condition is what most believe gave him such an interest in sports. His doctor recommended that he attend the Schmidt Institute of Sports and later the institute of Jan Malýpetr.

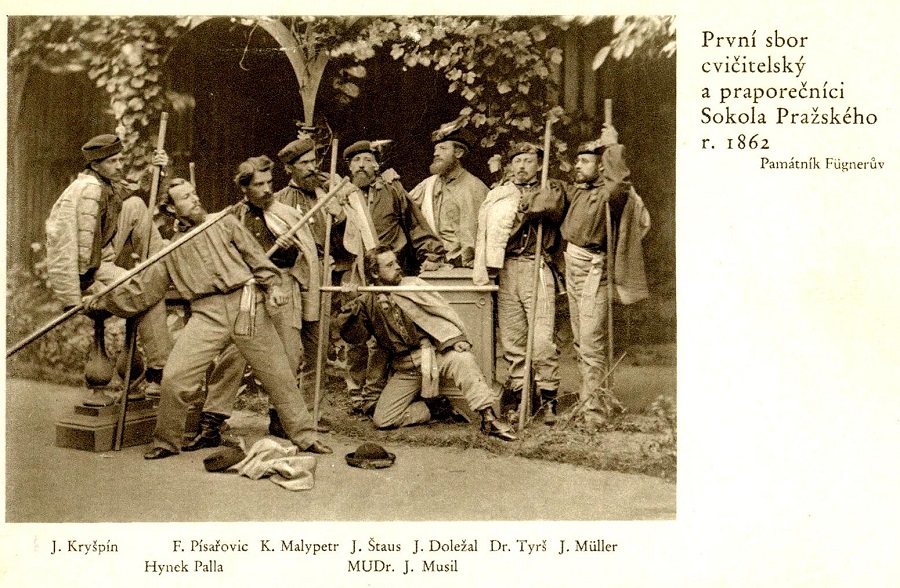

After this, he taught sports to the sons of a businessman in Nový Jáchymov and made up new sports terminology for them. In February of 1862, he together with Jindřich Fügner, his father-in-law, founded Tělocvičná jednota (Physical Training Union) which adopted the name Sokol (proposed by Emanuel Tonner two years later.

As a born German he wanted the club to be open to all the nationalities but Germans in Bohemia refused to be in the same club with Czechs, so Miroslav Tyrš changed his mind and started promoting the new club as bringing the Greek ideal only to Czech people. He saw in his teachings a kind of opposition to the German “folkish” virtues established by Friedrich Ludwig Jahn.

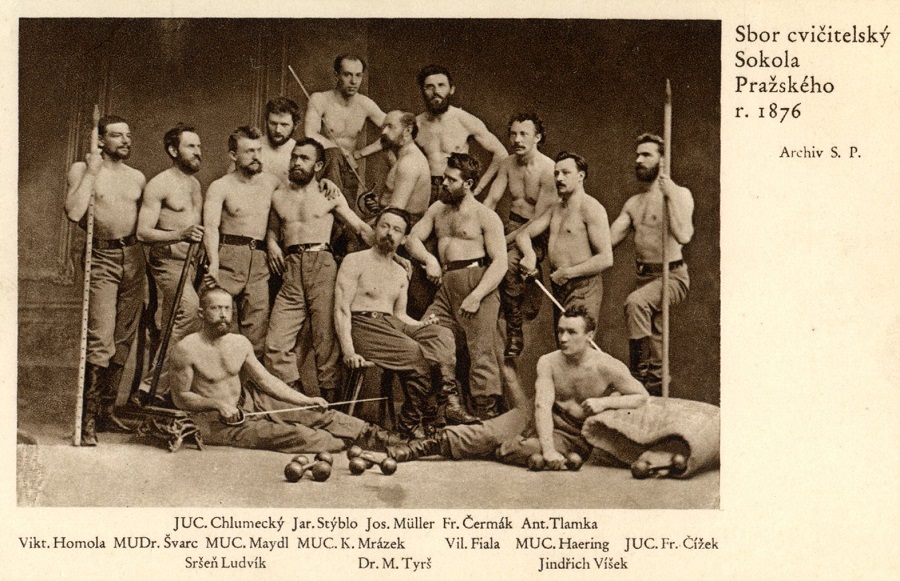

First Sokol president Jindřich Fügner, introduced the members’ habit of calling each other brother and sister. Their costume was designed by Josef Mánes. Miroslav Tyrš became first vice-president. After the first trips to Říp and Závist the movement became widely popular among Czech patriots and, in 1863, there were over 2,000 members. Tyrš introduced the physical training system and nomenclature in Základy tělocviku (Basics of Physical Training) in 1865. He also introduced a Renaissance-like architecture of Sokol gymnasiums.

Now on to the article written in 1920…

The thirtieth anniversary of Tyrš’ death (August 8th, 1914) could not be celebrated in Czechoslovakia as intended.

War had just broken out, and the Sokol’s were compelled to leave their country to fight against those with whom, in peace time, they would have honored amicably the memory of the founder of the Sokol-union. Years have passed since August 1914. The Habsburg-Roman combination which intended to exterminate the whole Czecho-Slovakian Nation had to recognize that there can be no victory in a fight against Justice and that the dream of Tyrš – Freedom of Czecho-Slovakia – had been realized.

Reality proved many of his sentences by which he encouraged his nation to intense work and true life; “The destiny of nations never has been decided on battle-fields; it was already determinated before the fight. No nation in the world, even if small, can perish so long as it is strong and valorous. Only decayed nations perish.” – “No external power, no material or brutal force can destroy a nation. As long as it follows the path of truth and public progress, it is invulnerable as a sunbeam, and perfidy and violences are powerless against it.”

The persecution of the Czech people became more and more brutal, yet hatred against Austria entertained common discipline. All were united in hate and in love. Abroad in Russia, France and Italy a new generation of God’s warriors arose, ready to struggle and die for the freedom of those who are “at home”. They never doubted but that victory would come to those whose cause was right.

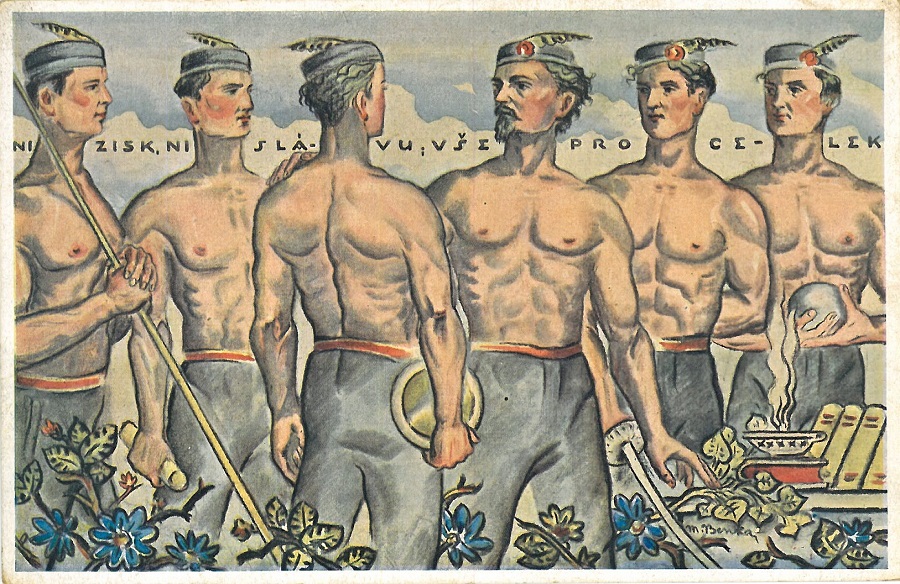

Personality is nothing – totality is all.

“The fewer we are, the more reliance will be placed on every man. Let us prepare ourselves for a better future by exercising our body and our mind.”

After a half century Tyrš’s plans were known in the widest circles of the Czecho-Slovakian people. The Sokols became the representatives of the common desire for national freedom and the promise of better times in the future.

The Sokols began with gymnastic exercises and soon concentrated around themselves the greater part of national society. Oppressing conditions did not permit them to free the country by an act of common revolt; yet they always prepared for the victory of our fight, and prepared well. The meetings of the Sokols soon became national festivals. Their educational influence was very large. It is an incontestable historical fact that the Sokol-union, which has been founded by scholars and humanitarians (Tyrš, Fügner, both Gregers, Tonner, Černý, Náprstek), has been accepted with enthusiasm by the large masses of our people, chiefly on account of its democratic and national principles. Yet, numbers alone did not raise the level of the union. Intelligent people remained outside the organisation, on the plea that its activity was not serious enough.

They did not take part in the activities of the union and went even so far as to see in the Sokol-union remains of past romantic times. Yet the Sokol idea was too strong, too full of life, and therefore, could not perish. Having taken root in the people, it gathered strength and grew with it, winning finally even those who had turned away from it at the beginning. The idea of Tyrš led our people in its struggle for freedom, taught it the duty of the present hour and the importance of order and discipline in moments of sorrow or joy. Common hate against the oppressors united the whole nation and prepared it for the decisive hour. The discipline, admired in our people during the revolution, was but the result of Tyrš’s work.

When in the October days of 1918 Sokols, workmen and soldiers began to “keep order” in the streets they met a people voluntarily disciplined. Wherever they appeared, obedience was assured. Our people were too well prepared for this hour, they esteemed too highly this historical day to stain it by revenge.

Even this was the result of Tyrš’s educational work. History will show that Tyrš also largely influenced our dear Legionaries.

Therefore, I dare say that Tyrš was one of those who assured the freedom of our nation. How often have we cited and read his article “Our task, direction and aim” (written in 1870) from which are taken the following sentences:

“In a healthy nation there is no room for treason, indifference and cowardice; totality is higher valued than parts, the interest of the nation is more esteemed than the interest of individuals. In such a nation no one will betray the common cause; all will persevere bravely to the end. Only a healthy nation is able to defend itself. A sword in each hand! Military organisation! Yet, above all, able-bodied and brave men! He who wants to insure the defense of his nation during war, must preserve it from corruption during peace. Let it be the guiding star of all our doings, the religion and the highest consecration of all our life.”

Thousands of warriors have given up their lives for their country, yet the commandment of Tyrš “to insure the defense of our nation” was abandoned for a still higher aim: to insure our freedom.

In July of 1860, Miroslav Tyrš was proclaimed doctor of philosophy at the University of Prague. 28 years old (he was born at Děčín on September 17, 1832), he was, up to this time, hardly known in Prague society; yet, soon afterwards, he began to intervene in the awakening of national life. Having been refused admittance as a lecturer at the University of Prague, he decided to become a writer.

On February 16th 1862, he founded the Sokol-Union in Prague.

Together with Jindřich Fügner, a humanitarian of high intellectual culture and his best friend, he began to propagate democratic ideas and to work restlessly on their realization. Having founded a gymnastic club – seemingly but a trifling enterprise – Tyrš knew already at that time that he was preparing a work which would take deep roots in the whole country.

He had no predecessor. Ideas and organisation, from the beginning to the end, were his own work. He had studied history and knew how important a part health plays in the evolution of a people. Darwin, “the immortal Briton”, had persuaded him of the necessity of the “struggle for life”, a fight in which health

is the best arm. Bodily health and strength are the first conditions of courage, perseverance and readiness for action: they are therefore indispensable for the preservation of the species. In order to suppress brutality and violence, strength must be mastered by discipline.

Voluntary discipline ennobles the heart, educates firm characters, and disposes us to self-denial and self-sacrifice, when common interest demands it.

Miroslav Tyrš was deeply convinced of the connection between morality and physical health. If Karel Slavoj Amerling has said, “every Czech must be twice as diligent than foreigners are” (Tyrš has a similar sentence: “Between all nations of the world, the Czech nation needs it most to concentrate its strength on self-defense.”); if Purkyně has shown us the importance of independent scientifical and artistic culture, Tyrš has been the first not only in our country to teach that morality is of the highest value for the future evolution of a nation. Being convinced of the connection between health and morality (the history of Hussitism had given him proofs of it), he wished not only to prepare his nation for the brutal and material struggle for life, but he also desired to show to his people the ways leading to true life and common progress. If you read the critics and speeches of this “Darwinist”, you will be often surprised on finding how firm he is in the belief that only the highest Justice and the victory of the sublime principles of freedom, equality and brotherhood can smooth the cruelty of the struggle for life, the necessity of which he never doubted.

In his speech at the monument of Fügner, (1869) this enthusiastic idealist declared that “the Czechs will be the first members of this new church which once will rule the whole world.” Always and everywhere he condemned selfishness. Knowing the difference between immoral egotism and the morally admissible feelings of pride, of self-consciousness and of the desire of individual freedom, he became the propagator of brotherhood in the most human sense of the word… How far he got before his time!

In his article “The Philosophy of history”, (Rieger’s Encyclopedia, 3rd Volume) Miroslav Tyrš says: “He, whose efforts aim at mastering nature by industrious life and at freeing nations in order to further their evolution and at enabling them to join freely other civilized nations – that is our brother. Every one who knows the high value of national freedom must strive for it. Patriotism must direct ail our activity.”

To be free in society means to acknowledge its laws and to subordinate one self to them willingly.

“Personal interests have to be subordinated to the common ones and vanity must be suppressed,” Common interest and the public weal have to be the aim of all our efforts. The same qualities which once assured the victory of our forefathers – industry, moral virtue, valor – also became the aim of Miroslav Tyrš’s endeavors in the Sokol-union. Qnly an ethical and sublime nation can be persuaded of the necessity of progress and eternal evolution… “Rarely is a situation so perfect that amelioration is impossible.” Only an ethical nation feels an aversion against lazy contentment; only in such a country, every man is ready to confess his errors and to find pleasure in the inventions and the progress of other men, just as though they were his own!

According to Tyrš, perfect and methodical gymnastic exercises are the best way to high national aims, such as: valor, constant fresh strength, physical, intellectual and moral health.

Miroslav Tyrš experienced on himself the beneficent influence of gymnastics. Being the son of a delicate mother, he began to practice gymnastics on his doctor’s advice and trained himself until he actually became stout. In founding the first Sokol-union, he thought of a brotherhood of generous men devoted to the common cause and convinced of the equality of all. In his words, “the Sokol-union has been founded for all classes.”

If the physical education of the working-classes is well organised, so that the leisure hours are employed in rational gymnastic exercises, even national economy profits by it. Physical and intellectual ability to work suffers by every illness; it decreases by want of vigor.”If in individuals this decrease is negligible, it is nevertheless very considerable in the mass. It amounts to thousands or millions of men and constitutes a great and irreparable loss in national economy. This economical side of the question is so serious and commonly acknowledged that it is able to resist all prejudices.” (1877.) Tyrš always laid stress upon the equality of all men – as far as they deserve it as moral beings. His endeavors in the Sokol-union also aimed at the reconciliation of social contrasts.

He desired to introduce beauty end harmony into education. Greece had furnished him with models of physical beauty. He surely thought of Greek gymnastical education when he wrote: “There is an inner connection between the elegance of movements and a good structure of the body. Every harmonious movement requires control of the whole body, not only of the one part by which the movement is being executed. As each control of the body is connected with the activity of the muscles, and as each harmonious movement requires constant control, therefore constant exertion of the muscles, it results that strength, perseverance and an elastic dexterity are built up without which strength resembles to brute force. Beauty, strength, grace and usefulness do not preclude one another (the Greeks can serve as models); on the contrary, usefulness and strength profit by beauty and grace.”

Mere exercises on the bar do not content the artistic taste. The Sokol-idea means much more than mastership in gymnastic exhibitions. Calling gymnastics a spacious art, Miroslav Tyrš shows that every movement must have its aesthetic value. Dress instruments and buildings must be estimated by the same standard. In his article “Gymnastic exercises and Aesthetics” (1873), he laid stress upon aesthetic education and uttered the hope that the Sokol-idea would animate artistic creation.

According to Miroslav Tyrš, gymnastic halls have to be centers of national education. This program assures to the Sokol-organisation an honorable place in Czech social life. Its responsibility grows from day to day. The Czech people have to keep to — day their freedom and become a nation that is just to itself and unto others. Tyrš desired to see all Slavs united in the struggle for a sublime cause.

He firmly believed in their mission to propagate the principles of freedom, equality and brotherhood among men. His idealism was powerful and confident. He neither despaired nor gave up his work, even when his feeble body refused to bear the strain of his duties. Tyrš was convinced of the high importance and everlasting value of work and persevering activity. He was always on his guard to keep the Sokol-organisation from corruption and inner discord.

The original gymnastic methods and the pithy terminology of the Sokols are his own work.

He edited a journal and watched over the evolution of the organization. How happy he was in 1882, on the occasion of a Jubilee festival of the Sokol-union in Prague when leading 76 unions with 1600 members each – hailing from Bohemia, Moravia, America, Lublaň, Zagreb and Vienna – to the island of Střelecký where thousands of rejoicing people had assembled! Miroslav Tyrš articles, published soon afterwards in the “Sokol”, show the contentment of the happy leader. He has not worked in vain! The idea for the realization of which he has scarified many a day and night will live in the future!

Seeing his “cause standing on firm foundations”, he decided to concentrate his forces on a new aim.

He invariably paid great attention to aesthetics. Thanks to his profound studies and long travel in foreign countries he was thoroughly versed in aesthetical matters. Having been a second time refused admission to the University of Prague by a clique of German professors, he became a lecturer on the history of art at the Czech polytechnic school. Although in the years 1860 to 1870 he wrote but articles on Sokol-matters, he published in 1870 many critical and aesthetic essays on the conditions of evolution and success in artistic creation (1873), a translation from Taine (1873); on the laws of composition in plastic arts 1873 (unfinished); on the reform of Czech artistic life (1879), and on the law of convergence in artistic creation (1880).

In these essays he treated the genesis of the works of art which appeared to him the original expression of national creative forces. According to Miroslav Tyrš it is every nation’s duty to care for the education of its artists and its public. (This educational aim also led to his activity in „Umělecká beseda”, an artistic association.) Art must be national and characteristical. He studied the laws of genius, and showed how to understand works of art. He laid down five conditions of beauty, yet, above all, he valued the characteristic qualities of artistic works.

He was the first Czech critic of his time and fully conscious of the seriousness of his task (His articles were published in the journals: Osvěta, Světozor, Národní listy, and Zlatá Praha.) Having become the champion and defender of young Czech sculptors and painters, he enthusiastically propagated the work of Josef Mánes (“We let him nearly perish during his life; let us keep at least his beautiful work, left to such ungrateful heirs!”), of Jaroslav Čermák, of Myslbek, Šnirch, Ženíšek and Brožík. He was asked to give his opinion on artistic Juries and tho act as Critic on art expositions. He paid great attention to the artistic decoration of the National Theatre, rose against German schools, awoke interest for West-European art and intervened successfully in questions regarding the restoration of national buildings and works of art.

His feeling in these matters was very delicate, his comprehension of the style and the spirit of the time far above the opinion of his contemporaries. Intending to edit a History of plastic art, he prepared himself for it by profound studies. He wrote a series of articles, of which the following deserve mention: “Laokon” in 1872, “The model of Zeus of Otrikol” in 1874, “Phidias, Myron and Polyklet” in 1879, “On the Gothic Style” in 1881, and “On the Importance of Studying Ancient Oriental Art: in 1883. In 1884, he reluctantly relinquished his activities in the Sokol-union and devoted himself entirely to scientific studies. Since 1882 he was lecturer on history of art at the University of Prague and in 188, he occupied the chair of assistant-professor on the same subject.

On his promotion he was so weak that he could not leave his room to take the prescribed oath. He suffered from headaches, giddiness, and sleepless nights. His forces began to wane after the arduous strain. The doctors advised him to take a rest. And in July 1884 he started for Tyrol, Austria.

In the village of Oetz-on-the-Aach (Ötztal, it is an Alpine valley in the western Austrian state of Tyrol) he took a room in the inn of Tobias Haida, and used to take long country walks. He was always alone. On the morning of the 8th of August, a Friday, he went to the village Lautens whence he returned no more…

He was declared missing on the evening of August 8th and found 13 days later on August 21st in the Ötztaler Ache river. After a national funeral he was buried in Olšany Cemetery in Prague next to Jindřich Fügner on November 9, 1884.

A chronicler says that “the whole nation wept for him, a proof that he had worked for all”.

For many years he had prepared himself for a great work on plastic arts. For a long time he suffered from the hostility of the government and from the ill-will of some competitors who prevented him from becoming a lecturer at the University of Prague. Fate cheated him of success in both of these enterprises. He did not finish his work as he was called too late to the university of his country.

One work, however, he did finish, The Code of Citizenship.

Our warriors have shown to Europe the results of his education; even in the far future its elements will be known. There is no doubt but that Miroslav Tyrš’s work will be esteemed by all progressive men, and that even many among us will read him more attentively.

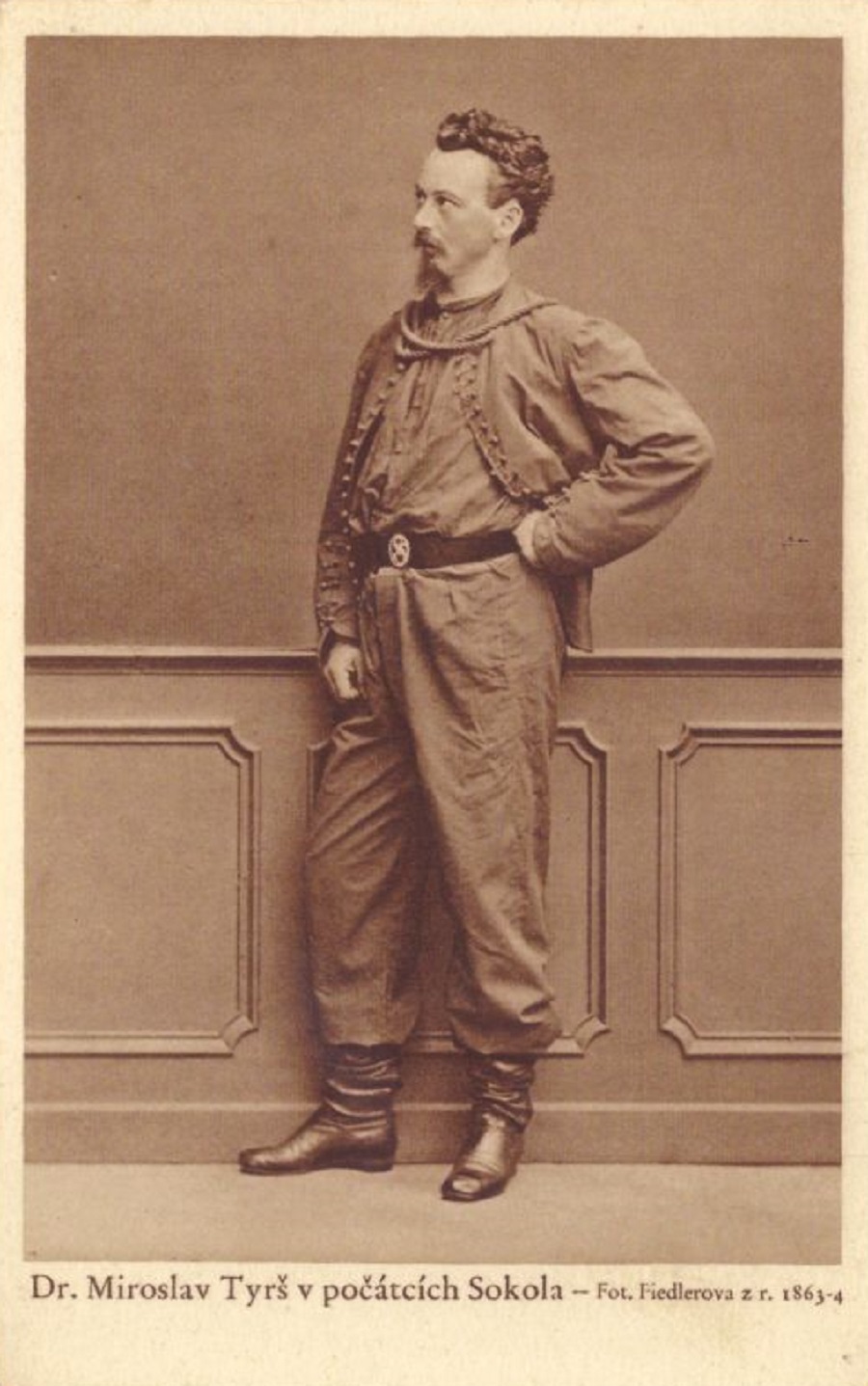

Miroslav Tyrš was an exact and logical thinker, an idealist full of confidence. His personal appearance is thus described by the Sokol Josef Müller, Tyrš’s contemporary and collaborator. – “Miroslav Tyrš was a man of middle stature, broad-shouldered and deep chested. He had an erect gait and a sharp eye. Black, dense, waved hair adorned his head. He used to comb it back, so that the broad and high forehead was kept entirely free. The look of his brown eyes was generally kind; only when something base provoked him, a short lightning could be observed. His nose was proportionate and slightly hooked, his beard short. The beautiful virile face was lightly sunburnt and of an energetic and noble

expression.”

Originally written by Karel Domorazek and published in 1920 by the library of the Czecho-Slovakian Foreigner’s Office as part of The Great Czecho-Slovaks series. Published in memory of Livingstone Porter 1894-1955.

Our addition –

Below is a film from June of 1941. It is the Sokol movement sports competition from Soldier Field in Chicago.

This fascinating full color, silent home movie from June of 1941 shows the American Sokol Slet, a gymnastics and sporting competition, held in Chicago including Soldier Field.

The film begins with important members of the organizing committee meeting to plan the games. At 1:27, a sign announcing the games is seen at the Sokol headquarters and shortly thereafter is a title card noting that for three days competitions in diving, gymnastics, swimming and athletics were held in Douglas Park, Pilsen Park, and the Sokol Chicago gymnasium. Various sporting events are seen including track at 5:40, women and then men’s gymnastics at 6:40, etc. At 18:00, a swimming and diving competition is shown with ladies posing in one-piece swimsuits, and men at 20:10. At 20:15, rehearsal is seen at Soldier Field. At 25:58, the crowded parking lot of Soldier Field is seen on the day of the big event, and a color guard is seen at 27:00 marching across the field. The flag is saluted and the competition begins, with an enormous crowd in attendance including Colonel V.S. Hurban, the Czech ambassador to the USA. The Polish ambassador is also shown at 34:00, J. Ciechanowski.

The Sokol movement (from the Slavic word for falcon) is an all-age gymnastics organization first founded in Prague in the Czech region of Austria-Hungary in 1862 by Miroslav Tyrš and Jindřich Fügner. It was based upon the principle of “a strong mind in a sound body.” The Sokol, through lectures, discussions, and group outings provided what Tyrš viewed as physical, moral, and intellectual training for the nation. This training extended to men of all ages and classes, and eventually to women.

The movement also spread across all the regions populated by the Slavic culture (Poland (Sokół), Slovene Lands, Serbia (SK Soko), Bulgaria, the Russian Empire (Poland, Ukraine, Belarus), and the rest of Austria-Hungary (e.g. present day Slovenia and Croatia)). In many of these nations, the organization also served as an early precursor to the Scouting movements. Though officially an institution “above politics,” the Sokol played an important part in the development of Czech nationalism, providing a forum for the spread of mass-based nationalist ideologies. The articles published in the Sokol journal, lectures held in the Sokol libraries, and theatrical performances at the massive gymnastic festivals called slets helped to craft and disseminate the Czech nationalist mythology and version of history.

The Slet are milestones in the life of the Sokol movement. They are periodic gymnastics festivals, surveys of what has been accomplished in the past working period and demonstrations of individual and collective achievement in the field of physical culture. To the Sokols, they are as significant as the Olympic games were to the ancient Hellenes. The Slets are organized on a regional, national and international scale. The most significant and the most famous, however, are the international Sokol Slets, held every six years at Praha, Czechoslovakia (Prague, Czech Republic).

The first slet was held in 1882, in celebration of the twentieth anniversary of the founding of the Sokol organization, and was presided over and directed by Dr. Miroslav Tyrs. Every subsequent Slet reflected the amazing growth of the movement and the spreading of the Sokol idea far beyond the national frontiers of Czechoslovakia. This constant progress is probably best documented by the growing numbers of gymnasts participating in the various Slet events and in the growing number of countries represented. While the first Slet in 1882 was, more of less, a local affair with 720 gymnasts taking active part, the tenth Slet, held in 1938, was a significant international affair, with more than 250,000 gymnasts participating actively in the gymnastics displays – among them Sokols from all over the world. Transcending all man-made barriers – national, social and political – the Sokol Slets have become manifestations for international understanding and brotherhood. This film is part of the Periscope Film LLC archive.

Tyrš did not study art or art history but he received proper education from Robert von Zimmermann, visiting art galleries in Germany, France, Italy and England and reading art history books (Johann Joachim Winckelmann, Gotthold Ephraim Lessing, Friedrich Schiller, Arthur Schopenhauer, Hippolyte Taine, Herbert Spencer, Henry Thomas Buckle, Karl Schnaase, Gustav Friedrich Waagen, Franz Theodor Kugler, Anton Heinrich Springer, Johannes Overbeck and Giovanni Morelli).

His first book on aesthetics was Hod olympický (Olympic Feast, 1868), an ode to Greek arts and sports. In his next book O zákonech kompozice v umění výtvarném (The Law of Composition in Art, 1873) he distinguishes three kinds of art work: 1. more content than form, 2. balanced, 3. more form than content. His study O zákonu konvergence při tvoření uměleckém (The Law of Convergence in Creating Art, 1880) he argues that both form and content should be submitted to the artist’s idea. The idea is influenced by external conditions which he described in his other important books O slohu gotickém (Gothic Style, 1881), Láokoón, dílo z doby římské (Laocoön, Masterpiece from the Roman Times, 1873), Phidias, Myron, Polyklet (1879) and the unfinished Raffael Santi a díla jeho (Raffael Santi and his work, 1873, published 1933).

Tyrš saw an ideal type of Czech-Slavic men and women in the paintings of Josef Mánes but on the other side he did not think highly of Mikoláš Aleš. His life interest and greatest monograph was focused on the life and work of Jaroslav Čermák (1879). Among the world painters he appreciated mainly Eugène Delacroix.

Tyrš’s work on Láokoón was denied by the professors at Philosophical Faculty of Charles-Ferdinand University in Prague in 1879 and so he applied for the title of docent at Czech Technical University in Prague. He succeeded after an appeal and became a teacher at the university. When Charles-Ferdinand University split into Czech and German universities, Tyrš was appointed docent (1882) and then professor (1883) of art history at Philosophical Faculty of the Czech university. His first lectures focused on the art of Orient. He signed a contract on writing The History of Art for Jan Otto, but died at the start of the work. Tyrš was also a member of a jury to assess projects for the Prague National Theatre building in Prague.

Note: Arthur Schopenhauer (1788 – 1860) was a German philosopher. He is best known for his 1818 work The World as Will and Representation (expanded in 1844), wherein he characterizes the phenomenal world as the product of a blind and insatiable metaphysical will. Proceeding from the transcendental idealism of Immanuel Kant, Schopenhauer developed an atheistic metaphysical and ethical system that has been described as an exemplary manifestation of philosophical pessimism, rejecting the contemporaneous post-Kantian philosophies of German idealism. Schopenhauer was among the first thinkers in Western philosophy to share and affirm significant tenets of Eastern philosophy (e.g., asceticism, the world-as-appearance), having initially arrived at similar conclusions as the result of his own philosophical work. Though his work failed to garner substantial attention during his life, Schopenhauer has had a posthumous impact across various disciplines, including philosophy, literature, and science. His writing on aesthetics, morality, and psychology influenced thinkers and artists throughout the 19th and 20th centuries. Those who cited his influence include Friedrich Nietzsche, Richard Wagner, Leo Tolstoy, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Erwin Schrödinger, Otto Rank, Gustav Mahler, Joseph Campbell, Albert Einstein, Anthony Ludovici, Carl Jung, Thomas Mann, Émile Zola, George Bernard Shaw,Jorge Luis Borges and Samuel Beckett.

There are wonderful photographs of Sokol slets in America at the Sokol Museum website.

Recommended Reading

- Dr. Miroslav Tyrš: The Founder of the Sokol-union by Karel Domorázek

- Dr. Miroslav Tyrš, founder of the gymnastic organization Sokol: His underlying principles and arrangement and classification of gymnastic activities by Josef Cermak

- Sokol gymnastic manual: English equivalent based on the original Czech version of Sokol system of gymnastics by Miroslav Tyrš the original English version by Charles Bednar

- Vsesokolsky Slet / 1948, Praha (Czech Edition) by Jaroslav Strnad

Thank you in advance for your support…

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

We appreciate you more than you know!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.