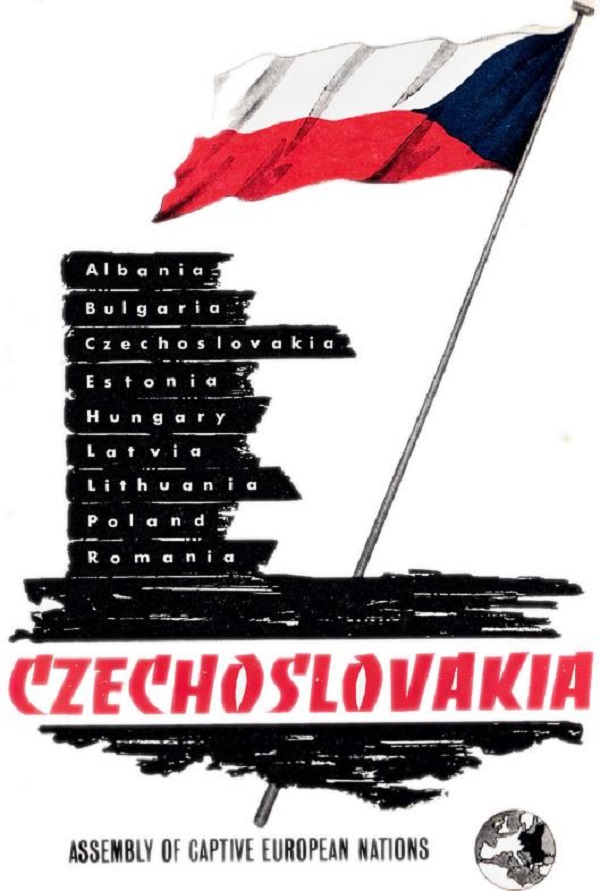

Today we are looking at Czech & Slovak literature through 1964. I write “through 1964” because the information comes from a booklet entitled Czechoslovakia by the Assembly of Captive European Nations Czechoslovak Committee. It was published in 1964 and was volume 3 in a series of nine booklets. I found their writing on literature interesting and wanted to share it with you today. Please let us know in the comments section below, what you think or what you believe is missing from this article.

Czech Literature

The beginnings of Czech literature rose from the missions of the brothers Constantine and Methodius, who brought to Moravia the first Slavic literary language and alphabet (later called the “Cyrillic”). They translated into Old Slavonic parts of the scriptures and the basic liturgical books.

This literary tradition in Church Slavonic ended in the 11th century, with the establishment of Latin as the liturgical language in the Kingdom of Bohemia.

The earliest writings in Czech were legends, epics, chronicles, and religious pieces. An epic poem, Alexandreis, and the Dalimil Chronicle are the outstanding works of the early 14th century.

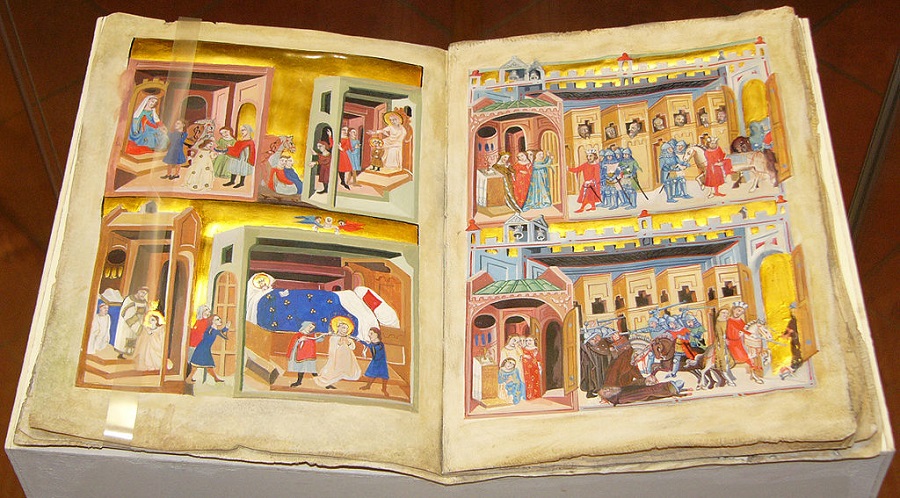

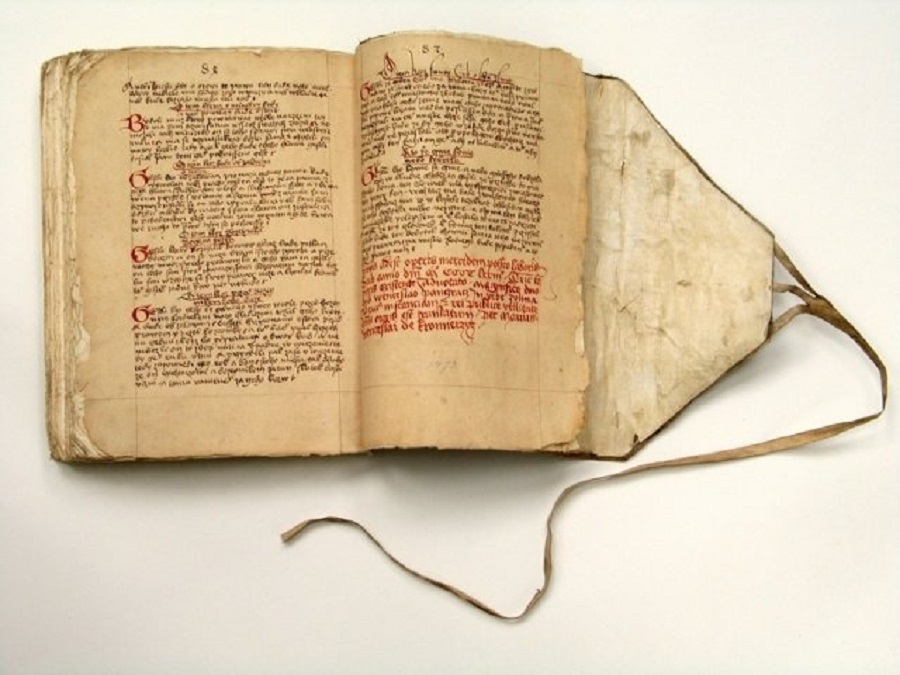

Dalimilova kronika; Kronika tak řečeného Dalimila

Czech literature was given a powerful impetus when the Charles University was established in Prague, in 1348. Emperor Charles IV himself also encouraged and supported scholarship and literary activities, Czech writing during the 14th century was characterized by richness of language and poetic skill, notably in the verse allegory Nová rada (New Council) by Smil Flaška and in the sermons in prose by Tomáš Štítný.

The writings of Jan Hus (1369-1415) reflected the ferment of the early Renaissance and launched the Czech religious reformation. Hus also contributed to the modernization of the Czech literary language. His philosophy had a lasting impact on Czech national thought.

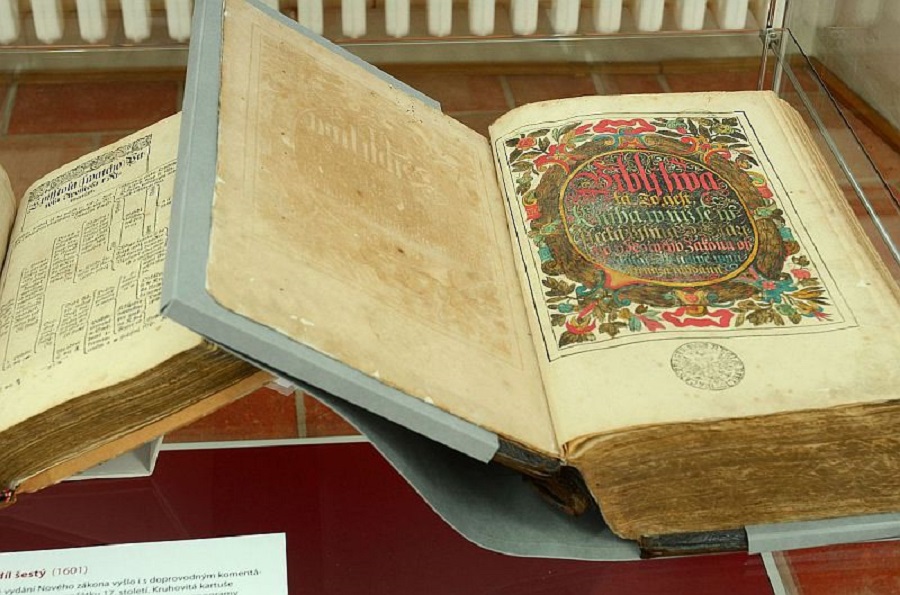

The Hussite wars led to a temporary literary stagnation. But the period produced the mystic Petr Chelčický (1390-1460), whose ideas led to the foundation, in the mid-15th century, of the Union of Bohemian Brethren, which considerably influenced Czech literary life. One of the scholars and literary critics among the Bohemian Brethren, Jan Blahoslav (1523-1571), contributed a translation of the New Testament to the Czech Bible (the Bible of Kralice), a masterpiece of the Czech language.

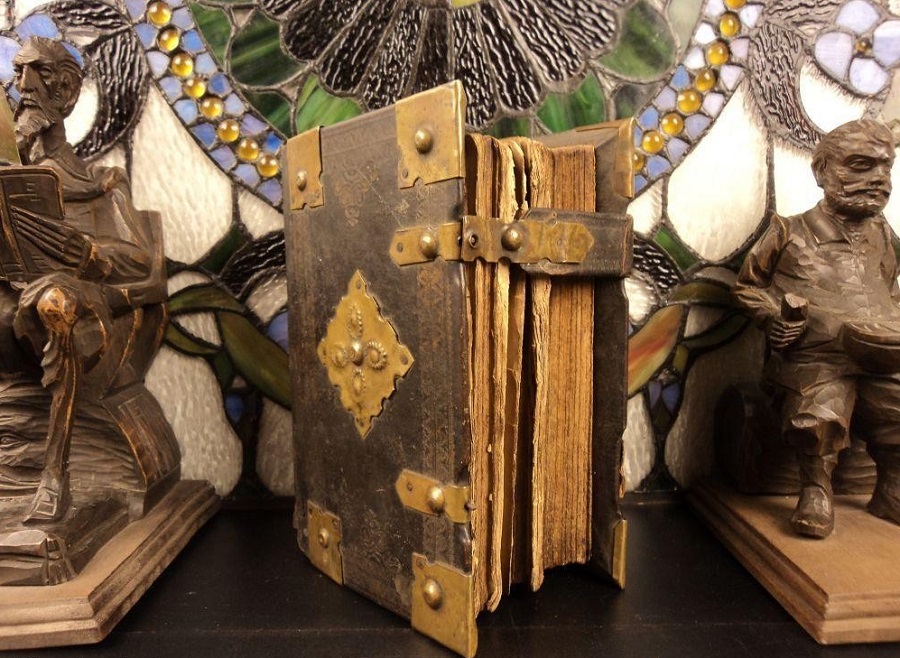

Kralice bible, photo: archive of National Library

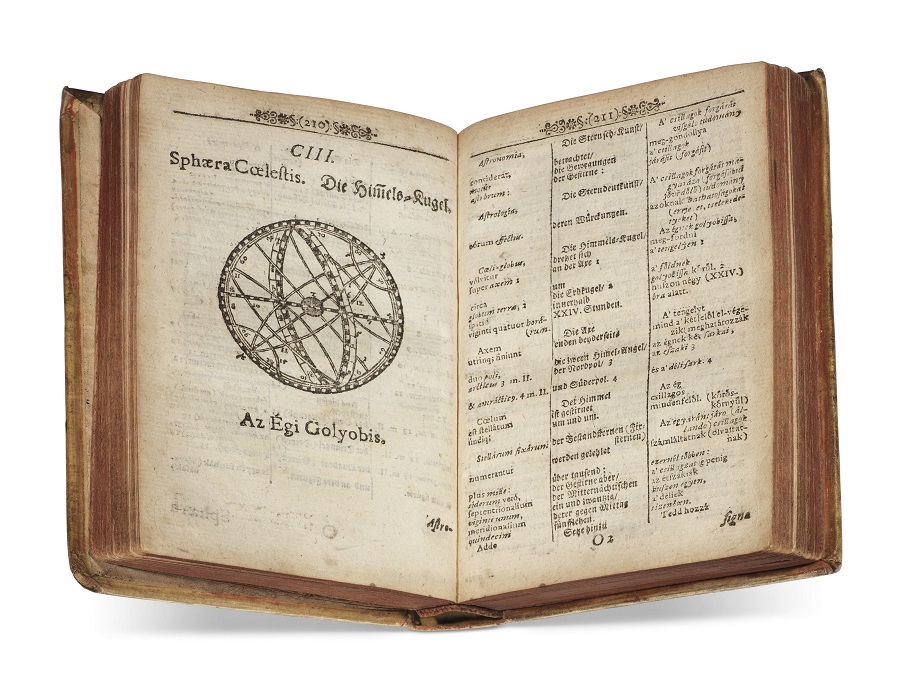

The Czech defeat in the battle of the White Mountain in 1620 had disastrous consequences for Czech literature. Religious persecution, especially of the Bohemian Brethren, left the cultural life impoverished. In the darkness of the 17th century towers the figure of Jan Amos Komenský (1592-1670), better known as Comenius, the last bishop of the Bohemian Brethren. This founder of modern educational methods and philosopher of world renown was forced to spend most of his adult life as an exile in Poland and Holland. Many of his writings deal with questions of religious and political freedom. Two of his Catholic contemporaries also deserve mention; Bedřich Bridel (1619-1680), and the Jesuit historian, Bohuslav Balbín (1621-1688).

The Czech national revival at the end of the 18th century saw its first beginnings in literature. Leading writers worked to rehabilitate the Czech language. Josef Dobrovský (1753-1829), the founder of Czech literary criticism, was the first to codify the Czech literary language. The national revival reached its peak in the works of these four authors: Josef Jungmann (1773-1847), a linguist who greatly enriched the Czech literary language; Pavel Jozef Šafárik (1795-1861), a Slovak philologist, archaeologist, and literary historian; Ján Kollár (1793-1852), a Slovak advocate of idealistic cultural Pan-Slavism; and František Palacký (1798-1876), author of the first modern Czech history.

Literary romanticism brought new life to Czech literature in the 19th century and created a wider interest in folklore. At one end of the spectrum of romantic poetry stands Karel Jaromír Erben (1811-1870), who combined, in his formally simple verse, a folklorist demonism with optimism.

At the other end looms the contrasting figure of Karel Hynek Mácha (1810-1836), a poet of anxiety and despair, whose revolutionary role was recognized only after his death.

A reaction to the idealism and sentimentalism of the National Revival became apparent in the work of Karel Havlíček Borovský (1821-1856), a poet and brilliant journalist. Božena Němcová (1820-1862), the first Czech woman writer, laid the foundations for modern Czech prose.

The Maj literary group, which appeared in the second half of the 19th century, concerned itself largely with political and social problems. The poet and critic Jan Neruda (1834-1891) was the group’s most eloquent spokesman—a voice often tinged with bitter irony. In another important development of that period, Czech literature branched out and followed its national and cosmopolitan paths. Writers who stressed the national element include Svatopluk Čech (1846-1908) and the historical novelists Alois Jirásek (1851-1930) and Zikmund Winter (1846-1912). Cosmopolitan tendencies prevail in Julius Zeyer (1841-1901) and Jaroslav Vrchlický (1835-1912), an important innovator.

At the turn of the century, new trends appeared. Critical realism predominated in the poetry of Josef Svatopluk Machar (1864-1942) and in the naturalist novels of Karel Matěj Čapek-Chod (1860-1927). Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk exerted great influence as a political and social critic. Modernism in poetry had as its main representatives the impressionist Antonín Sova (1864-1928) and Otokar Březina, the greatest of the Czech symbolists.

Slovak Literature

The first recorded Slovak text is in Žilinská právna kniha, Žilinská kniha (The Law Book of Žilina) of 1473. Slovak was established as a literary language, however, only in the mid-19th century.

The Law Book of Žilina

Cultural contacts between Czechs and Slovaks led to the use of the Czech literary language in Slovakia, especially by Slovak Protestants. After the Thirty Years’ War, for instance, many more literary works were produced in Slovakia than in the Kingdom of Bohemia.

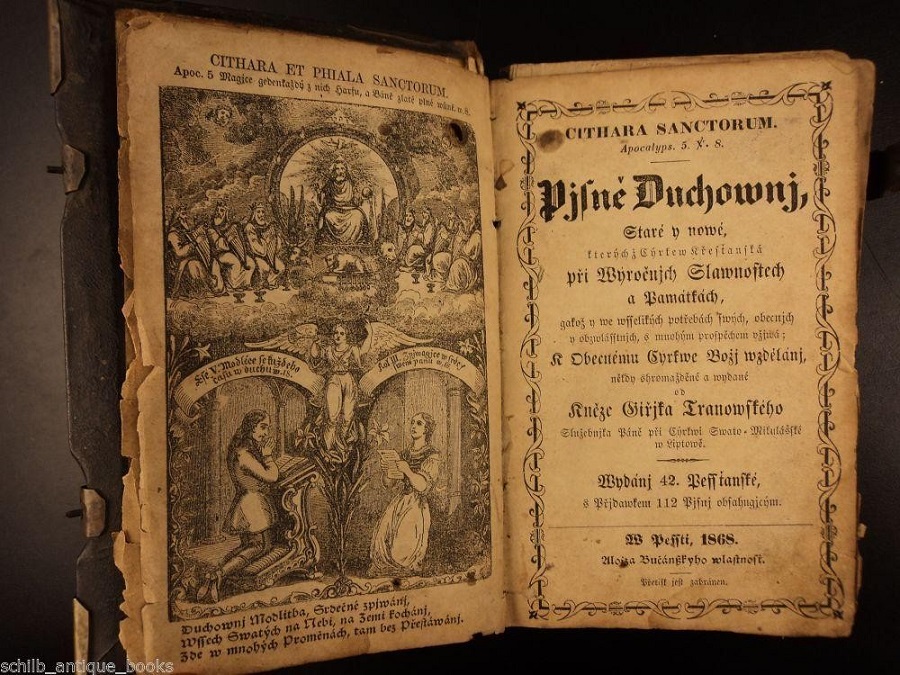

An important event in Slovak literature was the publication of the Protestant Hymn Book by Jiří Třanovský in 1635. Other Slovak authors, among them the outstanding historian and geographer Matthias Bel, wrote and published in Latin. The two Slovak universities, in Bratislava and Trnava, were cosmopolitan institutions and contributed little to the development of Slovak letters themselves.

Hymn Book by Jiří Třanovský

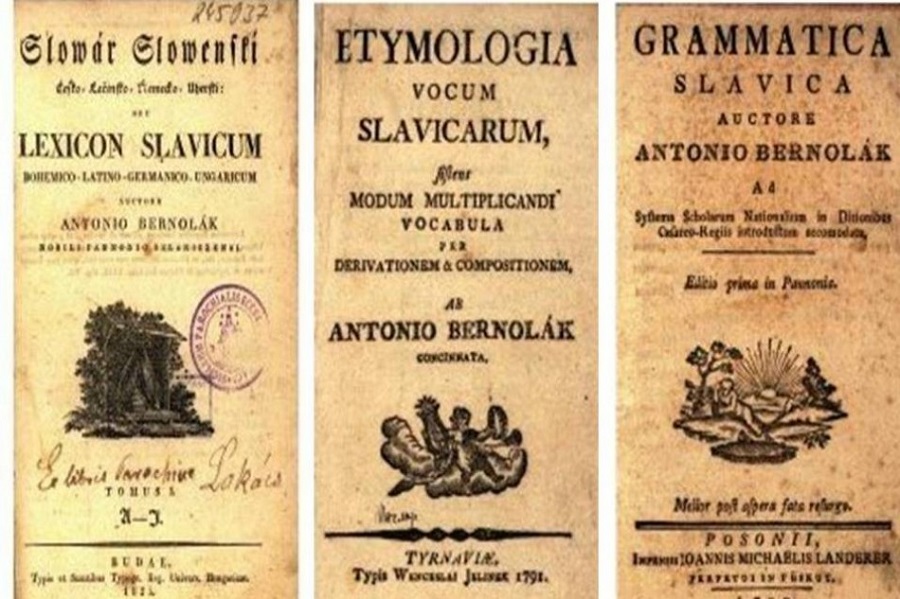

At the end of the 18th century Anton Bernolák (1762-1813), a Catholic priest, made the first serious effort to establish a Slovak literary language, using the Western Slovak dialect for his grammar and dictionary. Several leading writers published their books in Slovak: the poet Ján Hollý (1785-1849), and the prose writers Juraj Fándly (1750-1849), and Jozef Ignác Bajza (1755-1836), among others. The Slovak Protestants, however, did not accept Bernolák’s language, and Slovakia’s literature split into Czech and Western Slovak divisions.

The gradual expansion of the Slovak national revival hastened the ascendancy of the Slovak literary language over the Czech. In 1840, Ľudovít Štúr (1815-1856), the most remarkable figure of 19th-century Slovakia, introduced a new Slovak literary language based on the Central Slovakian dialect. It was immediately accepted by both Catholics and Protestants. Several important poets composed works of enduring value in the new literary language: Andrej Sládkovič (1820-1862), Samo Chalupka (1812-1883), Janko Kráľ (1822-1876), and Ján Botto (1829-1881). Other genres also developed. Ján Chalupka (1791-1871) and Ján Palárik (1822-1870) wrote plays. Martin Kukučín (1860-1928) was the first important realistic novelist. Elena Maróthy-Šoltésová (1855-1939), Božena Slančíková-Timrava (1867-1951), and Milo Urban (b. 1904) also wrote outstanding novels.

Poetry continued to occupy a central role in Slovak literature. Among the traditionalist poets, Svetozár Hurban-Vajanský (1847-1916) and Pavol Országh Hviezdoslav (1848-1921) were outstanding. Modernists include the brilliant innovationist Ivan Krasko (1876-1958) and Janko Jesenský (1874-1945), and many others.

Sub-Carpathian Literature

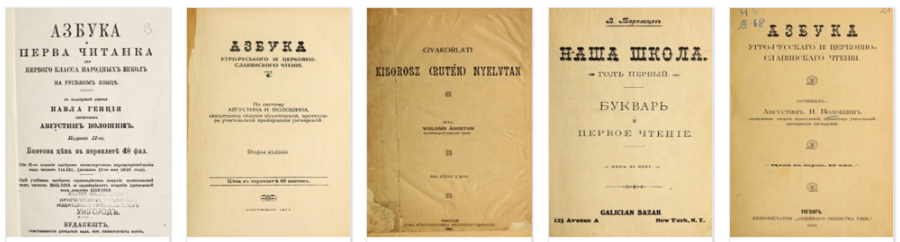

The language of the Sub-Carpathian Ruthenians is one in a group of Ukrainian dialects. The patriotic poet Alexander Duchnovič was one of the leaders of the 19th-century Sub-Carpathian Ruthenian national revival; in 1853 he published a Russian grammar as the basis of a new literature.

The important cultural Association of St. Basil the Great, founded in 1866 by Adolf Dobrjanský, made a rich contribution to the cultural life of the region. Sub-Carpathian Ruthenian authors of prominence are: A. Mitrak, Julij Ivanovyč Stavrovskyj-Popradov, the historian I. Duliškovič, the poets E. Fenik and Alexander Pavlovič, the prose writers Teodor Zlockij, Anatolij Alexander Kralický, I. Danilovič, Jurij Žatkovič and Jador Stripskij. After World War I their numbers were increased by Russian and Ukrainian exile writers.

Czech and Slovak Literature, 1918-1945

The arrival of national independence released new energies in the Czech and Slovak literatures, which developed along parallel lines. This was a period of vitality, ferment, and experimentation. Czechoslovak writers, no longer obliged to struggle for their country’s freedom, produced works truly cosmopolitan in character.

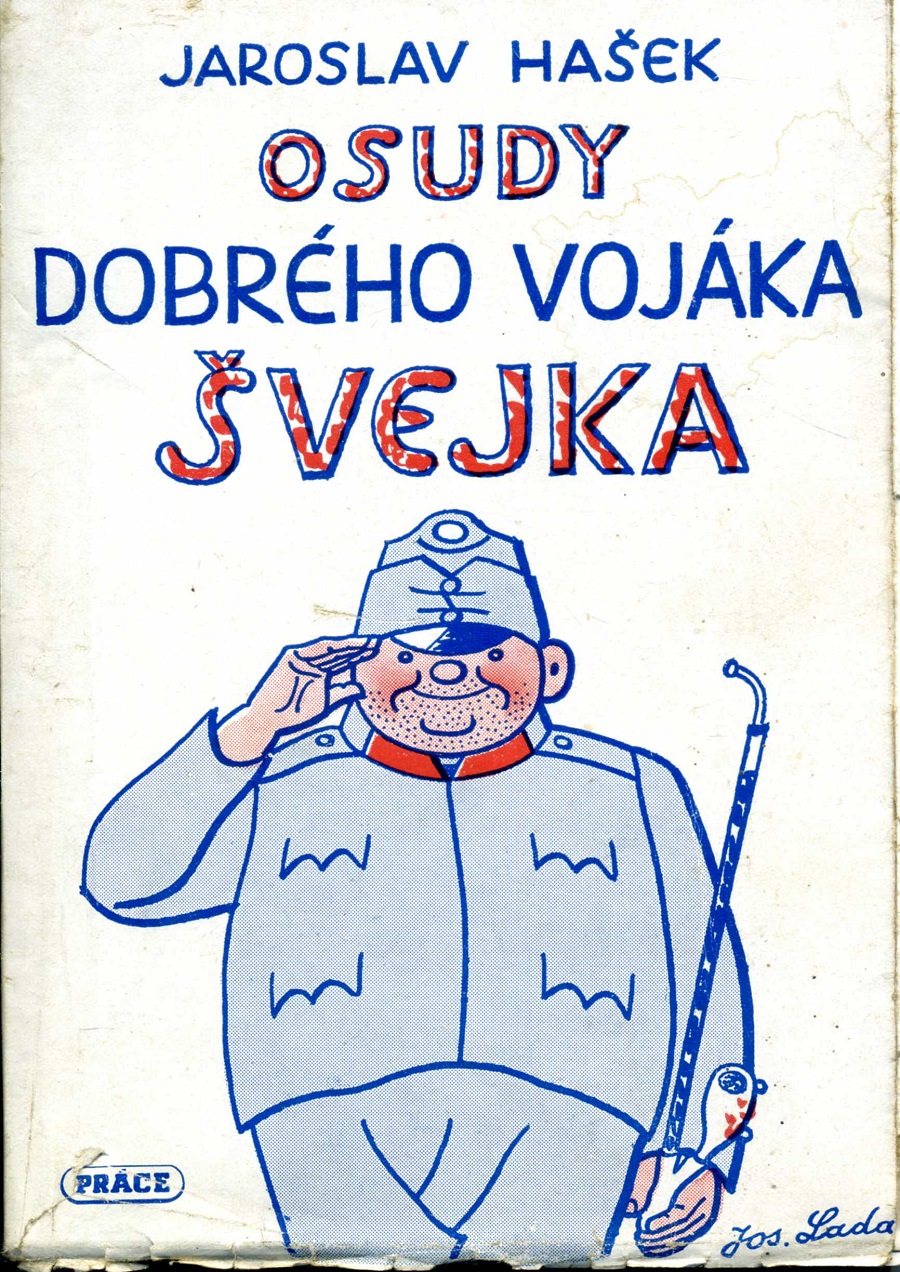

Czechoslovak literature entered the stream of world letters with the picturesque novel, The Good Soldier Švejk (or The Good Soldier Schweik), by Jaroslav Hašek (1883-1923), and with the visionary plays and novels of Karel Čapek (1890-1938).

An especially rich crop of poets appeared: Vítězslav Nezval (1900-1958), František Halas (1901-1949), Josef Hora (1891-1945), Jaroslav Seifert (b. 1901), and others. Most members of this group belonged to the school of “pure poetry.” The many prose writers of importance include: Vladislav Vančura (1891-1942), Ivan Olbracht (1882-1952), Jan Čep (b. 1902), and Egon Hostovský (b. 1908). The latter two elected to go into exile after the Communist coup and are (as of this writing in 1964) continuing their work in the West.

Literature under Communism

The Communist coup of 1948 forcibly removed Czechoslovak literature from the mainstream of Western culture. The Communist Party immediately established state control over the arts and declared the basically humanist tradition of Czechoslovak letters as inimical to the people. Marxism-Leninism became the only admissible philosophy, “socialist realism” the only aesthetic norm. Enforced conformity replaced creative exploration. Czechoslovak writers suffered from methodical “purges”—condemnations, and even imprisonment.

Writers who had placed some hopes in the Communist system were soon disabused. The depth and bitterness of their disillusionment is evident in the testament of the poet František Halas, written shortly before his tragic death in 1949.

Some writers, such as Vítězslav Nezval, chose to submit, and offered their talents to the Party. Hacks and functionaries assumed controlling positions in Czechoslovak letters.

But the Party has been unable to turn Czechoslovak literature into a Communist catechism. Interesting works, deviating from the official formulas, have managed to slip past the censors, especially in periods of uncertainty or transition. Most Czechoslovak writers continue their struggle for cultural and political freedom, as their forbears have done in centuries past. The political ferment in 1962-1963, for instance, which forced the Novotný regime to make some limited concessions, was spearheaded by the Slovak writers.

Note: The above is from a booklet entitled Czechoslovakia by the Assembly of Captive European Nations Czechoslovak Committee.

It was published in 1964 and was volume 3 in a series of nine booklets. Leave your comments below…

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Thank you in advance!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Become a friend and get our lovely Czech postcard pack.