Introduction

This paper explores a wedding custom practiced for more than one hundred years in the Chicago area by the descendants of Czech, Polish and Slovak immigrant women. Through the custom’s existence and perpetuation in America, the role of a transitional rite of passage is chronicled in both the process of assimilation and the preservation of ethnic heritage. The original textile symbols used in the ritual were modified to reflect the differences in culture in the United States, but with the “echoes” of European folk tradition still heard. Chicagoans today have continued to modify the custom as the role of women changes, and in the process, have create a form of American textile folk art.

The Folk Rite is a tunnel beneath history… that allows us to look far into our past.

-Milan Kundera

The European Matrix

To understand the roots of the American custom, identification by clothing in European agrarian societies of the nineteenth to early twentieth centuries must first be examined. Dress was a language, infused with meaning beyond mere fashion. Each region had an identifying style of dress, which announced to others, the locale, religion, social and marital status of the wearer.

Life changes were often accompanied by changes in clothing details, most particularly in women’s head wear at the time of marriage. An unmarried girl wore a floral wreath over her long hair for ceremonial and festive occasions, but the matron wore a cap or bonnet which covered all or most of her hair. In her work, classifying Slovak married women’s caps. Alzbeta Gazdikova notes their importance in folk life:

As late as the first half of the 20th century, the bonnet was still (in most of Slovakia) a part of folk dress which marked a woman's position -- it was worn uniquely by married women… the custom to cover a married woman's head … was of considerable significance. (This is) evidenced by the fact that bonneting a bride became a part of the traditional wedding ritual … among Slavs in general (113).

The capping ceremony, usually performed near the conclusion of wedding celebrations, remained essential in Poland. Even when festivities lasted a week, the groom was not permitted to exercise “his marriage privileges” until after the ritual had been enacted, making it more important than the church ceremony. Early marriage ceremonies were performed to secure the fertility of the union, rather than as a rite of solemnization, and not until the Council of Trent, in 1563,-was any ecclesiastical act necessary for the validation of a Christian marriage. The cap, then, not only identified the married woman, but also symbolized the promise of new life, and ultimately, the existence of the group. Other Polish folk customs have disappeared, but the oczepiny or capping, has survived to this day (Knab, 210).

Capping customs are thought of as part of peasant culture, but a late eighteenth century diary entry describes the ceremony at the wedding of a Polish noble:

In the middle of (the) dancing, a curious ceremony took place. A chair having been placed in the centre of the room, the bride sat in it while the twelve bridesmaids unfastened her coiffure, singing all the while in the most melancholy tone, "Barbara, it is all over then - you are lost to us, you belong to us no more." Her mother took the rosemary from her hair, and a little matron's cap of lace was placed on her head. (Hutchinson, 220).

Most Slavic ceremonies followed a similar pattern, with bridesmaids singing melancholy songs, mourning the loss of girlhood. The bride’s mother, godmother, or matrons of the village placed the cap on the bride’s head, and with songs of welcome, accepted her into the ranks of married women.

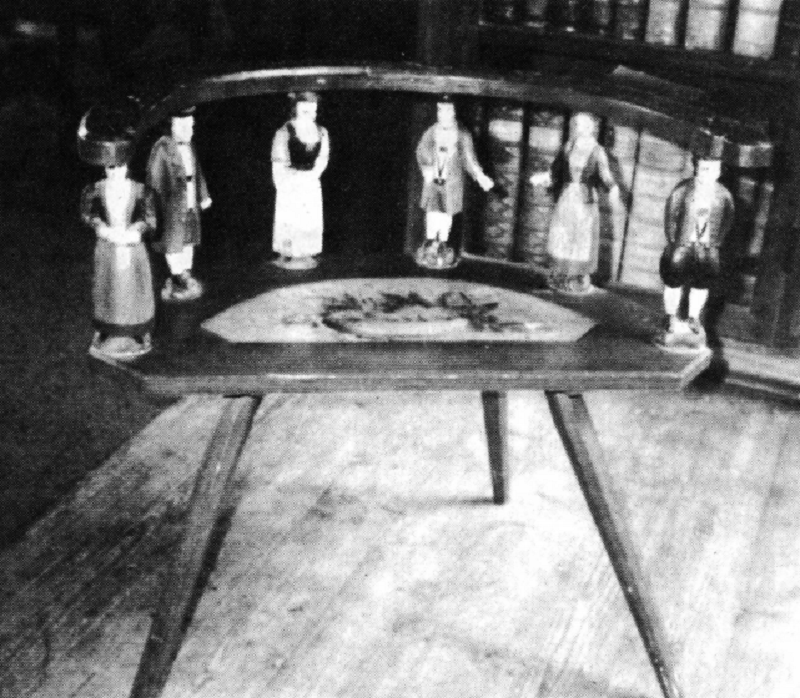

Further evidence of the ritual’s presence outside of the village setting can be seen today in the castle library on the estate of Krivoklat in Bohemia (Czech Republic), where an eighteenth century “capping chair” is kept. It was used solely for the brides of the estate to sit in while their headwear was ceremonially changed.

Milan Kundera, in his novel, The Joke, described not only the ceremony in Moravia (Czech Republic) during the post World War II era, but also the emotions created in the participants by its symbolism:

My friends staged a real Moravian (folk) wedding for me ... late in the evening, the bridesmaids removed the garland of rosemary from Vlasta's head and ceremonially handed it to me. They made a pigtail of her loose hair and wound it round her head. Then they clapped a bonnet over it. This rite symbolized the transition from virginity .to womanhood. Vlasta had long since lost her virginity. She wasn't strictly entitled to the symbol of the garland. But I didn't consider that important. At a higher and more binding level, she didn't lose it until the very moment when (the) bridesmaids placed her wreath in my hands ... the women sang songs about the garland floating off, across the water and ... it made me want to weep ... I saw the garland go, never to return. No return (128-129).

In earlier times, virginity was highly regarded. _Prior to World War II, the symbolism of the cap was so strongly associated with the loss of virginity, that unwed mothers were forcibly capped by village matrons in Moravian Slovakia (Bogatyrov, 72).

Cap styles,2 though differing from region to region, usually concealed most of the woman’s hair. After marriage, her hair was not seen again in public, due, in all probability, to its traditional association with sexual potency (Vlahos, 128). By covering her hair, the woman avoided tempting other men and kept her honor safe.

In some areas of Moravia, not even the husband was allowed to see his wife without her cap. It was believed that the cap had a magical function, bringing fertility and good fortune to the marriage; failure to wear it brought misfortune which could extend to the entire community (Bogatyrev, 52). Since family financial success could also be attributed to a woman’s diligence in keeping her hair covered, one well-off woman boasted, “The beams of my house have never seen my hair” (Vlahos, 134). Embroidered marriage caps were worn by Czech and Slovak women during childbirth confinement well into the twentieth century and seemed to represent a taboo.3 Although the composition of the embroidery was not understood by the wearers, they respected it in the same way as they did liturgical symbols (Vaclavik 29).

Every age has its symbols.

-Milan Kundera

American Adaptations

Custom is the essence of traditional societies and the core of custom is the expectation that nothing changes. In adapting to new circumstances, immigrants may abandon custom or find new ways to interpret it. John C. Messenger comments that reinterpretation of ritual is a universal phenomenon of acculturation, with borrowed elements interpreted according to traditional standards and indigenous elements according to borrowed standards (224).

During the thirty-year period from 1880 to 1909, seventeen million immigrants came to the United States. Over one-fifth originated in the Slavic regions of Europe, drawn largely from the agricultural classes and tied to a traditional way of life. One of the immediate cultural barriers they faced concerned dress. Letters from earlier immigrants advised those about to emigrate to leave village dress behind; wearing it made newcomers the object of ridicule. In order to avoid notice, many bought European urban fashions before they left. Those who arrived wearing folk costume purchased American style clothing as soon as possible. Assimilation, at least in the outer sense, was the goal of the immigrant.

The body … provides a basic scheme for all symbolism.

-Mary Douglas

Capping: Chicago Style

Population data indicates that the city of Chicago attracted large numbers of Slavic immigrants. It was the leading Czech-American metropolis in the 1860’s and by 1900, after Prague and Vienna, was the third largest Czech urban center in the world.4 Poles were also attracted to Chicago, which, with its highly centralized community of Polish immigrants, became known, by the mid-1880’s, as the American Warsaw. Of the Slavic groups in the United States, the Slovaks are outnumbered only by the Poles. They settled the industrial northeast and midwest, with significant numbers in the Chicago area. The essence of the capping ceremony was preserved in Chicago by these immigrants, who found ways to perform the ritual without using village dress.

A flowing white veil, modern American symbol of the fashionable bride, moved into the popular stratum of society during the same period as Slavic settlement occurred in

America. Prior to 1900, a wedding veil and white gown were usually worn only by the wealthy. In an effort to be fashionable, working class brides adopted the veil but paired it with a practical colored dress (Williams, 101). The veil and its accompanying floral elements, coupled with colored garments, likely served the immigrants as acceptable substitutes for traditional wedding wear.

Completion of the ceremony was dependent on the placement of the matron’s cap, which had no parallel in America at this time. It would be necessary to choose a different symbol of the married woman, one which conveyed a similar meaning, in an American way. The kitchen apron, worn almost constantly by nineteenth century housewives, became the new symbol through which immigrant mothers signaled the change in status to their American-born daughters. Families in the Chicago area who have perpetuated the custom, relate that the apron was part of family wedding tradition from the time of their earliest immigrant ancestor, a range of approximately thirty years, from 1870-1900. They were unaware of the original capping ritual and assumed that the apron ceremony had come from Europe.

The earliest immigrants who developed the Americanized version may have attached a deeper meaning to the apron. That it had significance in Europe beyond the utilitarian, is evidenced by its almost universal presence in ritual and festive costume. It functioned as the spiritual-magical protection of the sexual organs and fertility of the wearer, and as a ritual symbol, has been traced to the Neolithic period (Barber, 297; Gimbutas, 278). Folk embroiderers in Europe and those in America who learned the art from family members, have continued to repeat the old protective symbols found on aprons, in their work. Such symbols may be described as good luck signs, but are most often seen as a continuance of tradition, without regard for their original meanings (Kelly, 83-89; Cincebox, 74-77).

It may be speculated that the selection of the apron was guided by its association with fertility, in combination with the accepted idea of American housework. This agrees with Yoder’s comments that European rural populations have adapted factory-made clothing “in ways that still express folk cultural needs,” marking changes “selectively to their own ideas.” He saw this in the actions of country girls who wore peasant dress in the village and kept “modern” clothing for trips to the city (302-304).

If the idea of fertility was resident in the choice of an apron, the symbolic message of the veil and apron ceremony would have been altered in America by the descendants of the originators. Through loss of contact with their agraian heritage and its emphasis on fertility, the allusions to the sexual aspects of both the matron’s car: and the ritual apron would shift to emphasis on the new responsibilities of marriage. It is this idea which was cited by all present informants as the purpose of the ceremony.

The music is playing, cheerfully from afar.

-Joseph Sudek

Echoes of the Past

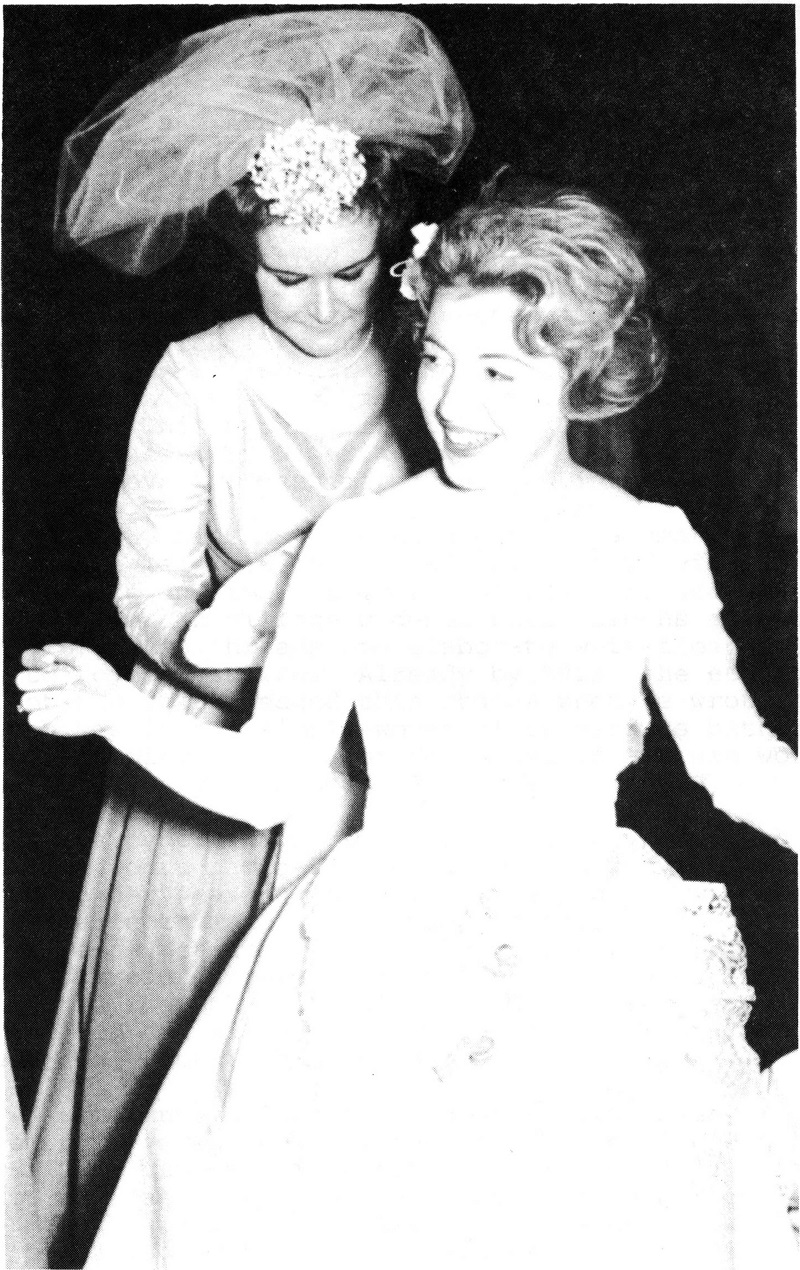

An early eyewitness account of the American ritual was given by a second generation Czech-American who was born in Chicago in 1904. She recalls seeing the ceremony as a child at the wedding of her uncle: Bridesmaids removed the veil of the seated bride, an apron was tied around her waist, and a peasant-style kerchief tied on her head. Wedding guests formed a circle and sang songs. The melancholy lyrics of European songs were usually replaced in America by love songs, but some informants were told that the ceremony should properly be bittersweet; a new family was being formed, but at a loss to the families of the wedding couple.

At some point in the first half of the twentieth century, the groom was actively included in the ceremony. He was given a symbol of shared responsibility which usually incorporated the idea of humor. One informant stated that while the groom held a wrapped baby doll, the bride vigorously waved a wooden spoon to remind him of his new responsibilities. Household symbols, like brooms or drain plungers, were also cited as items given to the groom.

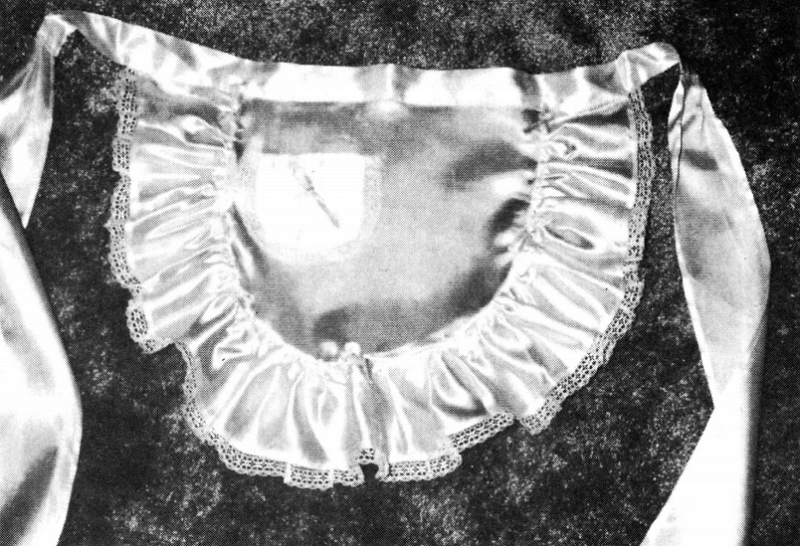

In the 1940’s, the bride’s utility apron was replaced by a delicate “tea apron,” made specifically for the occasion.

Photograph collection of the author.

In some families, it was bad luck for the bride to make her own apron. This task was the responsibility of the godmother, and parallels European culture, where it is the duty of the godmother to provide a wedding cap for the bride. Satin and lace aprons were decorated with ribbons and wedding rings. In some cases, the groom also wore an apron which was embellished with miniature tools.

The ancient idea of fertility returned to the apron during the “Baby Boom” era, when small dolls, representing future children, were added to the decorations.

baby dolls. Bride wears groom’s boutonniere in her hair. Photograph courtesy of Karen Barger.

One informant’s family determined the number of dolls by the number of ribbons broken while unwrapping gifts at the wedding shower. Each informant related minor differences in the details. In some ceremonies, the bride removed the groom’s boutonniere and placed it in her hair after her veil had been removed.

In the current climate of challenge to the traditional roles of women and men in society, many young women express distaste at the idea of an apron ceremony, linking it to an implication of subservience and male domination. Nonetheless, the strength of family and ethnic tradition have remained influential. Thro.ugh mixed ethnic marriages and friendships, brides of non-Slavic background have also chosen to include “aproning” in their wedding celebrations. Chicago suburban gift shops and The House of Brides, billed as the world’s largest bridal salon and wedding mall, sell aprons for brides without a family apron maker. Customers may add trimming to the basic white or ivory satin model. When questioned about the custom, a bridal consultant responded that although those of Polish descent placed more importance on the ceremony, it was, along with garter and bouquet throwing, “One of those cute things they do at weddings,” and had no ethnic reference.

The apron ceremony has survived as the product of an American subculture, with its continued use, as well as its abandonment, serving as an indicator of ethnic preservation. C. J. Hribal, writing of the resilient character of the immigrants, states that people adapt to circumstances and “reinvent their lives in the process,” sometimes “through flight carrying their histories inside,” and filtering everything new “through

that shell of memory.”

Conclusions: Why Chicago?

Why the veil and apron custom evolved in Chicago and not in other Slavic American settlements has not been conclusively determined. Informants who moved from the area reported that the custom was unknown in their new location, which they were surprised to learn; they had assumed it was done everywhere. Slovak families in Broome County, New York, have remained closely tied to the original European ritual since their arrival in America, around the year 1900. One informant was capped at her wedding reception in 1970, with a family heirloom. She was the fourth generation of brides to wear the family cap and has since constructed over a thousand replicas for Slovak-American brides. Portage County, Wisconsin, has the largest population of rural Polish-Americans in the United States, yet there is no tradition for capping or any modification of the ritual. In Cedar Rapids, Iowa, the sizable Czech-American community also has no history of either form of the custom.

There are factors which may have contributed to the differences in the degree of preservation or in the abandonment of the wedding ritual among Slavs in America. Some Slovaks outside of Chicago retained the original capping custom. Their background was entirely agrarian, but in America, they worked in factories or coal mines. Lack of a history as an independent country deprived Slovaks of a national identity, thus regional or village ties were strong. Preservation of an important ritual was a way to keep a sense of identity in a totally changed circumstance. They were a group who retained strong ties with their homeland, where many intended to return after earning money in America as unskilled laborers. Czechs and Poles outside of Chicago emigrated to small town and rural areas to settle permanently and were able to continue an agricultural way of life.

With a stronger sense of national awareness, Czechs and Poles were able to abandon ritual and still know who they were as a group. In small towns and rural areas the native language was retained longer than in urban areas, easing the transition. For Slavs who came to Chicago, pressures to assimilate were stronger. The large Slavic community was surrounded by earlier arrivals from other countries who had already assimilated, and economics forced those who had skills to become “Americanized” in order to compete.

End Notes

The majority of the Chicago Slavs were rural in origin, but cut off in America from an agrarian or small town lifestyle. This combination of factors may have accounted for the retention of the wedding ritual in an Americanized form.

- The word “cap” is similar in all Slavic languages: in Czech, čepice ; in Polish, czepek; in Slovak, cepiec. There are also local variants in spelling.

- As recently as the late nineteenth century, Poles and their eastern Slavic neighbors, particularly Russians, cut off the hair of the bride at the time of the capping ceremony.

- For a discussion of ancient symbolism and taboo in Slavic textiles, see Patricia Williams, “Childbed Curtains and Churching Shawls”; Ars Textrina Journal No. 21 June, 1994.

- Czechs were commonly known as Bohemians before 1918, since many came from what had been the Kingdom of Bohemia (which also had a non-Slavic German population). Presently, the Czech Republic is composed of the states of Bohemia and Moravia.

Authors Note

I have been able to observe the wedding custom, previously described, many times since my childhood. My ethnic heritage is Czech, and I share many of the same recollections as the informants interviewed. I have been a participant in “aproning,” both as a bridesmaid and a bride, in a family where it was always part of the wedding celebration.

During my research for this paper, I also searched out German wedding traditions since there is an overlap with Czech culture, and in the process solved a childhood puzzlement. My mother and her elderly relatives always referred to a woman who was romantically interested in a man, as having “set her cap” for him. Although I understood, even as a child, the implication of the phrase, the words never made sense. How could those words indicate a woman’s desire for a marriage? Maybe they really meant “setting a trap” for a man. Or did she “set her cap gun” in an effort to scare him into marriage? The old women stated that it was just a saying and didn’t need to make sense since everyone knew the meaning. I had forgotten about these childhood musings until I discovered a Styrian folk song in which the phrase “girls set their caps for boys,” brought it back. Knowing the headwear traditions and ceremonies surrounding them, the phrase finally made sense. It had arrived and survived in midwest America along with the immigrants.

I extend my thanks to the following individuals who provided information on family, friends and personal experiences: Kathleen Anderson, Karen Barger, Elizabeth Borovicka Capozzi, Lillian Endriz, Edna Fligel, Sylvia Jakubiec, Dennis Kolinski, Dorothy Kurtz, Nancy Lewandowski, Josephine Prochaska, Carol Palmer, Marianne Polli, Florence Rene, Betty Slabenak, Marie Slabenak, Florence Vodicka, Marianne Winters.

Works Cited

- Barber, E.J.W. Prehistoric Textiles. New Jersey: Prince on U.P., 1991, 471 pp.

- Bogatyrov, Petr. The Functions of Folk Costume in Moravian Slovakia. Trans. Richard G. Crum. The Hague: Mouton, 1971, 119 pp.

- Cincebox, Helene. “Czechoslovakian Folk Aprons.” Threads. 32 (1990-91), 74-77.

- Douglas, Mary. Purity and Danger. New York: Praeger, 1966, 185 pp.

- Gazdfkova, Alzbeta. Lenske epce v I’ udovom odeve. Trans. Peter Tkac. Martin: Vydavatelstvo Osveta, 1991, 120 pp.

- Gimbutas, Marija. The Civilization of the Goddess. San Francisco: Harper, 1991, 511 pp.

- Harvard Encyclopedia of American Ethnic Groups. Ed. Stephan Thernstrom. Cambridge: Harvard U.P., 1980, Czechs 261-272, Poles 787-803, Slovaks 926-934.

- Hribal, C. J. Introduction to The Boundaries of Twilight. Minneapolis: New Rivers P., 1991. 356 pp.

- Hutchinson, Henry Neville. Marriage Customs in Many Lands. London: Seeley, 1897. Republished, Detroit: Gale, 1974, 267 pp.

- Kelly, Mary. “Eastern European Motifs in the Work of Three Women Folk Artists.” New York Folklore XV, 1-2 (1989), 83-96.

- Knab, Sophie Hodorowicz. Polish Customs, Traditions, and Folklore. New York: Hippocrene, 1993, 304 pp.

- Kundera, Milan. The Joke. New York: Harper & Row, 1993, 267 pp.

- Messenger, John C. “Folk Religion.” Folklore and Folklife. Ed. Richard M. Dorson. Chicago: U of Chicago P., 1993, 217-232.

- Vaclavik, Antonin and Jaroslav Orel. Textile Folk Art. Trans. Helena Kaczerova. London: Spring, N.D, 280 pp.

- Vlahos, Olivia. Body the Ultimate Symbol. New York: Lippincott, 1979, 262 pp.

- Williams, Patricia. “Childbed Curtains and Churching Shawls.” Ars Textrina, Vol. 21 (June, 1994), 65-83.

- —. “From Folk to Fashion.” Dress in American Culture. Ed. Cunningham & Lab. Bowling Green, OH: B.G.U.P., 1993, 95-108.

- Yoder, Don. “Folk Costume.” Folklore and Folklife. Ed. Richard M. Dorson. Chicago: U. of Chicago P., 1993, 295-323.

Written by Patricia Williams in 1994, Ms. Williams is Associate Professor and Curator of Historic Costume Collection, Division of Fashion and Interior Design, University of Wisconsin-Stevens Point, Stevens Point, WI 54481. From the University of Wisconsin for the Textile Society of America, Symposium Proceedings and shared here via DigitalCommons@University of Nebraska – Lincoln. (Original source.)

You may also find the following post informative: The Wedding Tradition in Slovakia. (Lots of nice color photos and some videos!)

And in the following video (with lots of costumes, singing and dancing) you can see the capping at approx. minute 51.

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Thank you in advance!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.