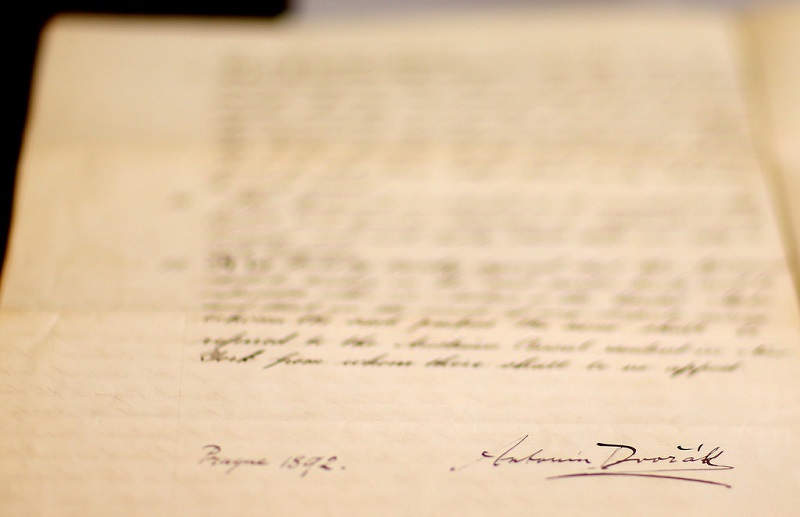

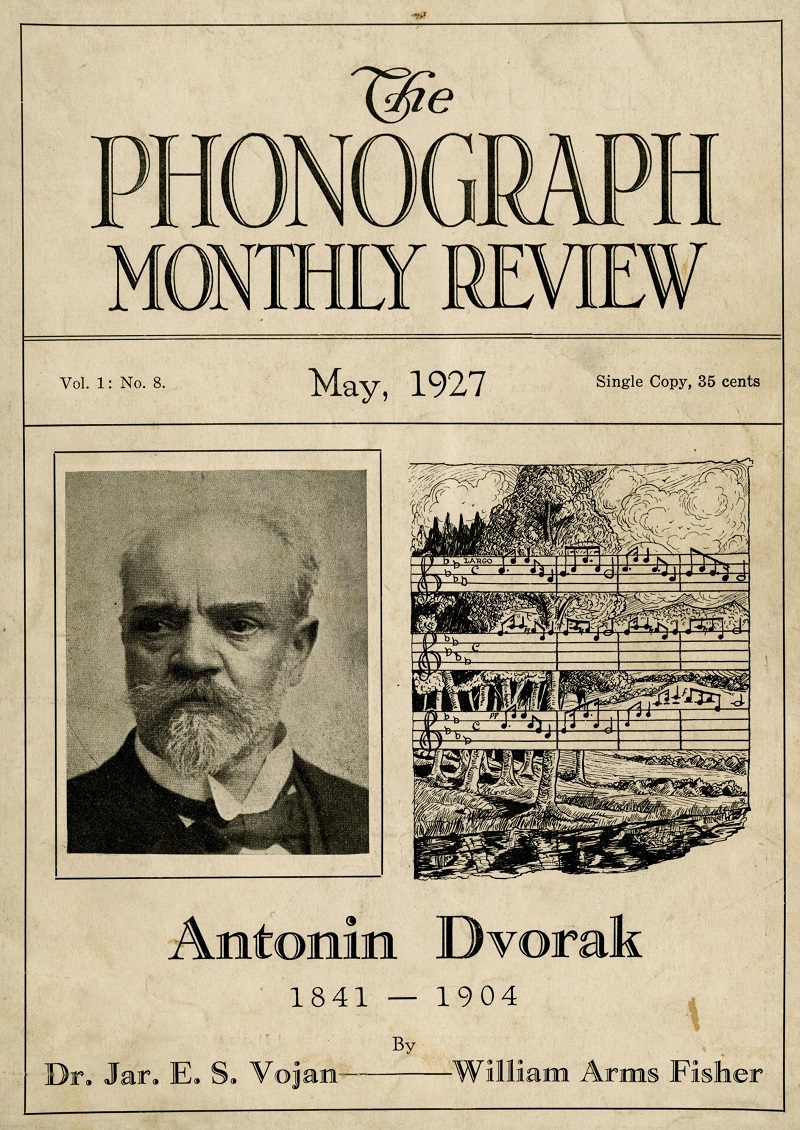

I must confess to being addicted in finding the most rare, forgotten, and set aside information. This very intimate reminiscence of Antonín Dvořák was written by William Arms Fisher and appeared in The Phonograph Monthly Review, Vol. 1: No. 8. May 1927. Without further ado, I’m sure you will enjoy this piece, especially if you are a Dvořák fan.

It was my good fortune to study composition and orchestration with Dvořák for two years when he was Director of the National Conservatory in New York. At the same time, I was an instructor in harmony in the institution and was therefore naturally brought into frequent contact with Dvořák .

I first saw him at the concert given in his honor in Carnegie Hall, October 21, 1892. As his pupil I came to realize how simple and modest by nature he was. New York tried to lionize him but the pose of a lion was altogether foreign to his nature and the noise and hurry of New York life only intensified his love of home. One day he spoke of this to me and said that sitting in the quiet of his home he loved most to read his Bible and Shakespeare.

I music his great fondness was for Beethoven and Schubert. One day he asked me to attend a rehearsal of the Conservatory Orchestra. They were playing one of Beethoven’s earliest symphonies. The playing was rough; the intonation was often faulty, so much so in fact that between two of the movements I asked the dear man how he could stand it. “Ah,” he said, “they are playing Beethoven and I would rather hear Beethoven badly played than not to hear him.”

His broad-minded catholic spirit toward music of every type, no matter how humble, was a dominant characteristic. He habitually stopped to listen to every itinerant street band, with its dented or cracked instruments, to every hurdy-gurdy, to the tunes whistled by boys and to the songs of the hour that lesser musicians scorned as unworthy of notice. On these occasions, Dvořák never failed to put his hand in his pocket for he, too, had been a street musician and understood.

With the same spirit with which Newton regarded a pebble on the beach he listened to every stray note of music. I well remember his once telling me how in the evening before he had been trudging through the snow with one of his boys to look in the windows of toy shops, for it was Christmas time, and the boy caught sight of a toy piano in the window and said Dvořák, “I looked and on the piano was a lettle musik und das musik waz gut, so I took out my pencil and wrote it down.”

When therefore with this eager spirit Dvořák for the first time heard Negro spirituals sung he became engrossed in them as something new and distinctive. He said, “They are the most striking and appealing melodies that have yet been found on this side of the water.”

His enthusiasm for them was that of a naturalist who in a strange land comes across in his rambles a new and to him hitherto unknown flower. This enthusiasm, this discovery, led Dvořák not to any literal transaction or direct use of Negro themes but after first saturating himself in the Negro idiom he embodied his delight in this new-found treasure in his Symphony from the New World, Op. 95, his String Quartet, Op. 96, and String Quintet, Op. 97.

It was my good fortune to hear the Kneisel Quartet read at eight on a Sunday morning at the Conservatory the Quartet and Quintet, an unforgettable experience. Mrs. Thurber, the head of the Conservatory, was of course there, a few of the faculty and the leading music critics of New York at that time, Krehbiel, Finck, Henderson, Aldrich and Spanuth. The Kneisel Quartet was on its mettle and read like men inspired. We were all thrilled. At that time I was in the choir of Grace Church when Samuel P. Warren was the organist, and I had to cut the morning service in order to have this wonderful experience. I ran the risk of losing my job but felt that didn’t matter.

When the New World Symphony was announced for public performance, the newspapers gave the work probably more advance publicity than has been given before or since to the first performance of an orchestral work in this country. Columns were written about the symphony and Dvořák’s theories, whereas he was not a talkative man nor a man of theories at all. He did have, however, the conviction that art in order to be healthy and to carry any national flavor must be rooted in the soil out of which it springs, and finding American composers everywhere absorbed in echoing trans-Atlantic strains and idioms he said “Here, in the music you have neglected, even despised, is something spontaneous, sincere and different, native to your country. Why not use it?”

That was all and I remember one morning when I went to his room at the Conservatory for my hour in composition, finding him walking up and down the room shaking a New York morning paper like a rag and exclaiming with heat, “See what they make me say! I did not say it. I’ll go back to my Bohemia.”

It was soon after this that he showed me a letter from his friend Hanslick, then Vienna’s chief critic, and was greatly comforted because Hanslick recognized in these works of Dvořák a fresh thematic element, a new trait and idiom denied them then by some American critics and still denied them by others.

One day in New York Dvořák said to me “I used to write a la Mozart, or a la Schubert or Schumann, but now I am myself.” This was after he had written his E minor Symphony and his Quartet and Quintet Op. 96 and 97.

The man’s flow of musical thought was extraordinary. Once he showed me the sketch for his ‘Cello Concerto first played by Victor Herbert). It consisted of a single page of music paper covered closely with pencilled scrawls evidently dashed down with the utmost rapidity. They were undecipherable to anybody but himself. At another time he said “To get ideas, that is easy, but what you do with them is the thing.”

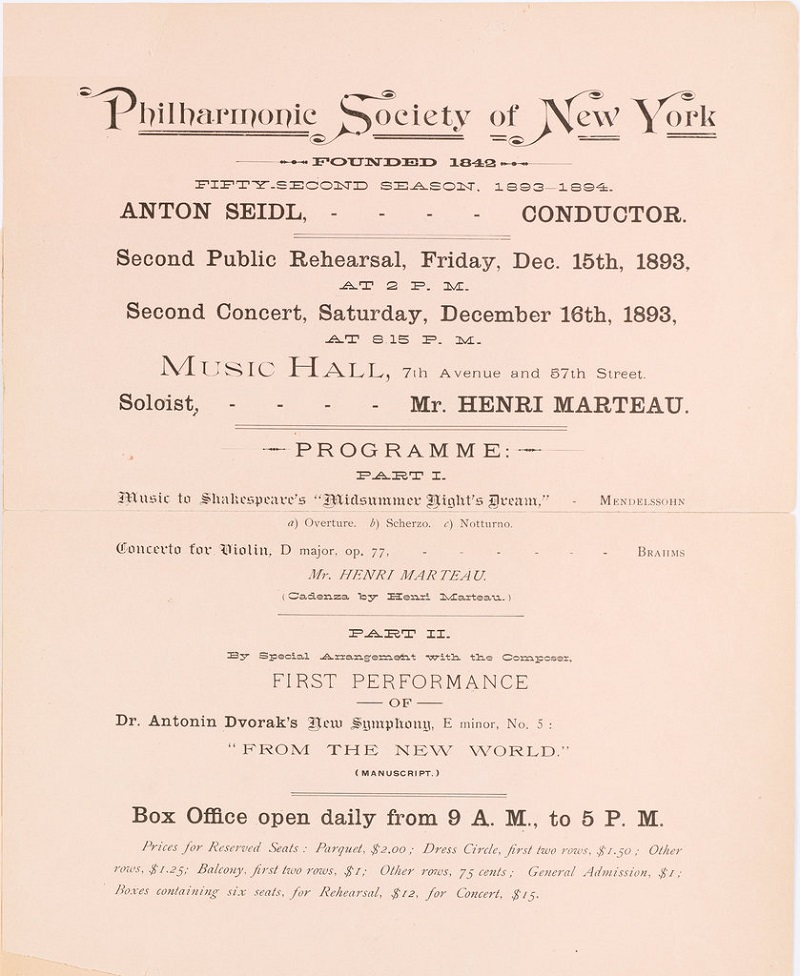

Perhaps Dvořák’s closest friend among the musicians in New York at that time was Anton Seidl, conductor of the Philharmonic Orchestra. I shall not forget Thursday, December 14, 1893. I had been having a lesson in orchestration with Dvorak and at its close he said in his usual mixture of German and English “Komm mit mir to Carnegie Hall. Seidl is going to rehearse my new symphony.” It was the last private rehearsal.

On the next afternoon at the first public performance Carnegie Hall was crowded to the utmost. At the close of the Largo, so moving was the performance, so touched to the heart was the great audience, that in the boxes filled with women of fashion and all about the hall people sat with the tears rolling down their cheeks. Neither before nor since have I seen a great audience so profoundly moved by absolute music. At the close of the movement and again at the end of the symphony, the modest, simple-hearted, peasant composer was persuaded with difficulty to rise and acknowledge the ovation given him.

This Largo with its haunting English horn solo is the outpouring of Dvořák’s own home-longing with something of the loneliness of far off prairie horizons, the faint memory of the Redman’s bygone days, and a sense of the tragedy of the Black-man as it sings in his Spirituals.

Dvořák told me after his return from the summer spent in Spillville, Iowa, that he had been reading Longfellow’s Hiawatha, and that the wide stretching prairies of the mid-West had greatly impressed him.

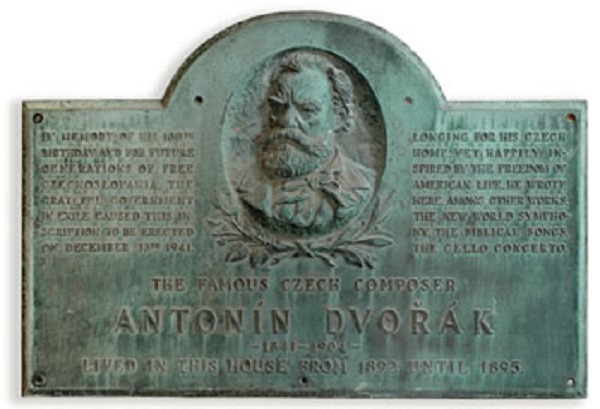

The last time I saw this unspoilable man with the heart of a child was at the end of April 1895, when over at Hoboken he stood on the deck of the steamer that was to carry him back to his beloved Bohemia.

Related Reading

- The Deal That Brought Dvorak to New York, New York Times.

- Did Dvorak’s ‘New World’ Symphony Transform American Music?, New York Times.

- Dvorak as Prime Mover, Sitting Duck and More, New York Times.

- Dvořák’s 9th ‘From the New World’, The Guardian.

- Dvorak and New York, Antonin Dvorak Website.

- The Dvorak House on 17th Street in New York, New York Architecture.

[We are very fortunate that so many people entrust us with such treasures for the online Czech museum, from where this periodical came.]

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

We rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Thank you in advance!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.