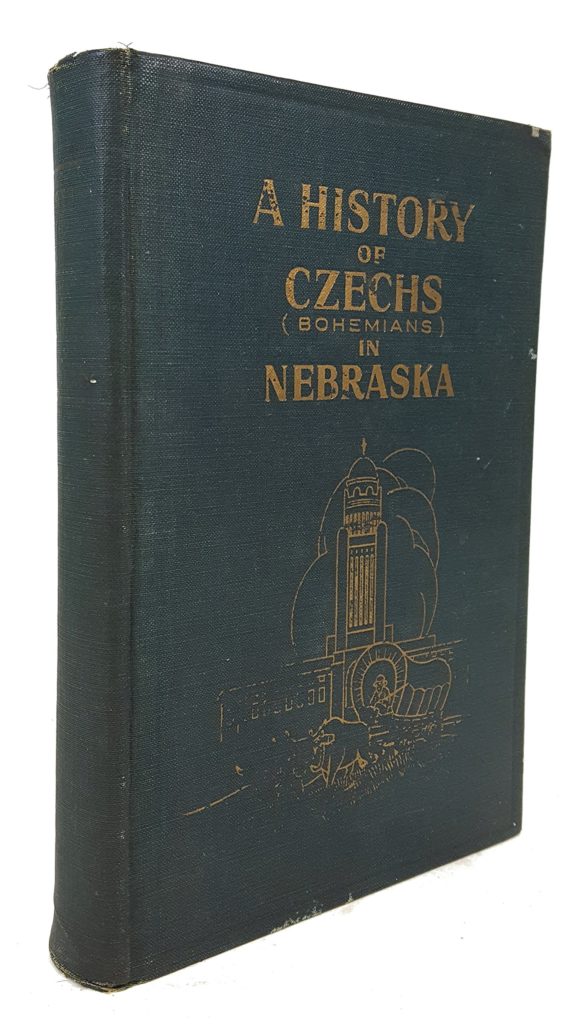

If you are a lover of Everything Czech and are especially fascinated with Czechs in America, then surely you have heard of the Rosický’s of Omaha or come across A History of Czechs (Bohemians) in Nebraska. Compiled by Rose Rosicky (Růžena Rosicka) in Omaha, Nebraska in 1929. This special historical book (documents all important Czech organizations, publications, schools, artists, religion, settlement of counties and other important things, in which Czechs in Nebraska have participated.

Rose Rosicky (Růžena Rosicka) was born July 22, 1875, in Crete, Nebraska to Marie and John Rosicky. She came to Omaha in 1876 as a baby when her parents moved there and she lived there until her death in 1954.

For many years she was her father’s secretary. After her father died, she became the Associate Editor of the Osveta Americka, Hospodar and Kvety Americke III. She translated Ramona by Helen Hunt Jackson and The Price of the Prairie by Margaret Hill McCarter in addition to many other stories and articles. She is responsible for editing five volumes of the Pioneer Almanac, for which she also prepared the translations. She also translated History of the United States by also S. E. Forman. All the foregoing were translations from English into Czech.

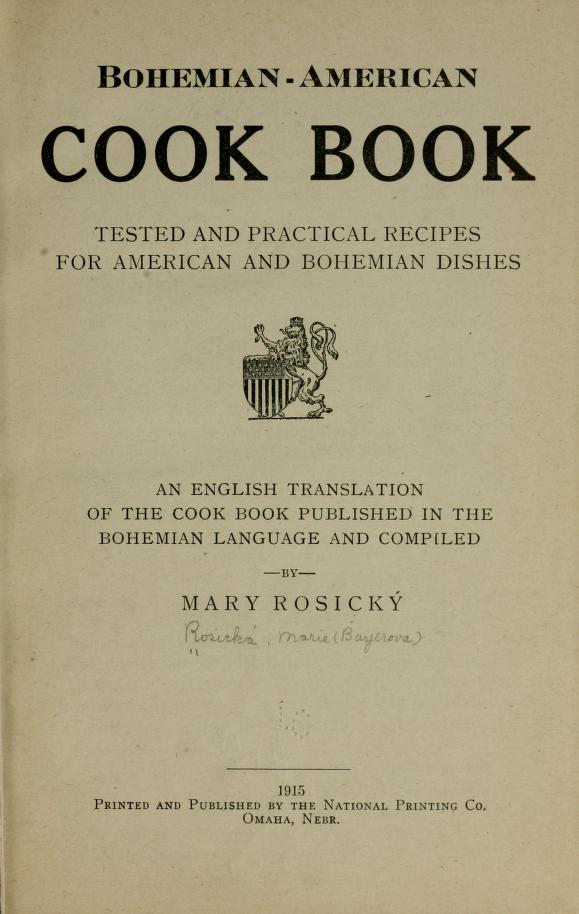

From Czech into English she translated her mother’s cook book Bohemian-American Cook Book, Tested and Practical Recipes for American and Bohemian Dishes (below) and other books and stories by the following leading Czech writers: Karel V. Rais, Gabriela Preissova, Ruzena Svobodova and Bozena Vikova-Kuneticka. She has compiled several handbooks for farmers and the home, as shown in the list of publications.

The Czechs did not leave their native land to establish a utopian society in America. They came to make a better life for themselves and their children.

Nebraska History, Fall/Winter 1993

You have also surely seen Bohemian-American Cook Book, Tested and Practical Recipes for American and Bohemian Dishes (An English Translation of the Cook Book Published in the Bohemian Language and Compiled by Mary Rosicky. Printed and Published by the National Printing Co., Omaha Nebraska 1915.

This book was written by Rose’s mother, Marie Rosicky. In the cookbook Rose writes some interesting things about the immigrants of the Czechs at that time…

I have translated the cook book compiled by my mother for two reasons: First, because we continually receive inquiries for a Bohemian cook book written in the English language, from the daughters of our Bohemian immigrants, who were born and raised here and do not read Bohemian as well as their parents. Second, to serve those American housewives who wish to try foreign dishes.

The Bohemian fathers and mothers deplore the fact that their children have Americanized so quickly, that in the second generation their mother tongue is half obliterated. We can see their side of it, those immigrants who left their fertile and beautiful land because long years of despotism, class prejudice, heavy taxation and other unjust vexations have made it well-nigh impossible for a poor peasant or laborer to better himself there. The average American can have no conception of what it means to tear one’s self up by the very roots, leave one’s native land and dearest relatives forever, start life anew in a strange country, and learn a new language.

On the other hand, we can see clearly the childrens’ side of the situation. They have been born, raised and educated in America, and this country will always be their home. Their parents’ land is to them but a picture or a story. Among our people in the country settlements the children talk and even read and write Bohemian to a greater extent than in the cities, but in any event it is safe to say that with the third generation the large majority cease to be Bohemians, except in name.

Each country has its special style of cookery, and I think that is one way of preserving the nationality to a certain extent and for a time at least, for we all like those dishes which our mothers prepared for us. If the daughters cook like the mothers did, and teach their daughters to do likewise, it will at least be a reminder of our parents’ native land.

As far as the demand of American housewives for foreign cookery books is concerned, that is no doubt brought about by the ever increasing custom of traveling abroad, which of course makes cosmopolitans of us. The average American, who travels only in his own country and does not live near settlements of industrious and progressive foreigners, generally has about three names for all Europeans, namely: Dago, Dutchman or Swede. Of the Slavs he usually knows nothing at all. It is different with the American who has been abroad. If he is at all intellectual and observing, he knows that there is culture and crudeness in all nationalities, and that aside from certain racial characteristics, we are all the same human beings, with the same struggles, sorrows, hopes, aspirations and problems.

Perhaps the present war has done more to open the minds of Americans to the status of the various nationalities composing Europe, and the relation they bear to each other, than anything else. And when it comes down to cooking itself, the real cook, no matter what her nationality, is always eager to try something new. I know that the American housewife will find many new and tasty dishes in this book.

My mother, Mary Rosický, was born in Klatovy, Bohemia, December 8th, 1854, and died in Omaha, Nebraska, October 9th, 1912, having come to this country when thirteen years of age. The women in her family were noted for their fine cooking, so that she acquired her art through a natural inheritance. However, while good cooking is in the main an inborn art, it can be learned by perseverance, patience and diligence. – ROSE ROSICKÝ.

Omaha, Nebraska, March 25th, 1915.

I’m personally fascinated with the Rosický’s of Omaha because mother, father and daughter were all involved in some sort of writing and publishing as am I with my daughters. Like the frustrated newpapermen and journalists of days gone by, oftentimes we feel like our leadership is also unappreciated. Sadly, we’ve also come close to closing this website down for lack of funds. This is why we can relate to this quote from Nebraska History, Fall/Winter 1993.

Newspapers were the most important medium keeping American Czechs aware both of happenings in the many Czech settlements in the United States and of developments in their native land. Between January 1860 and the spring of 1911, a total of 326 Czech newspapers and journals (predominantly weeklies) were published. Most were short lived, lasting less than a year. Their publishers and editors were for the most part self-educated men dedicated to helping and advising the new immigrants. Their leadership was not always appreciated. Readers often failed to pay subscriptions, causing the financial failure of many sincere and useful journalistic efforts. One editor, in announcing the demise of his weekly, wrote bitterly in 1874: “It is hard to make a living in America with a pick and shovel, yet it is even harder for a journalist. I am throwing away the pen which made three prime years of my life so miserable … I will not even say whose fault it is. I mention only that I could not publish the farewell issue of the paper because I lacked money to buy newsprint, even though the Czechs owed me $800.” On the other hand, religious, political, and ideological animosities among some competing newspapers ran high and, in many instances, contributed to bitter relationships among their readers.

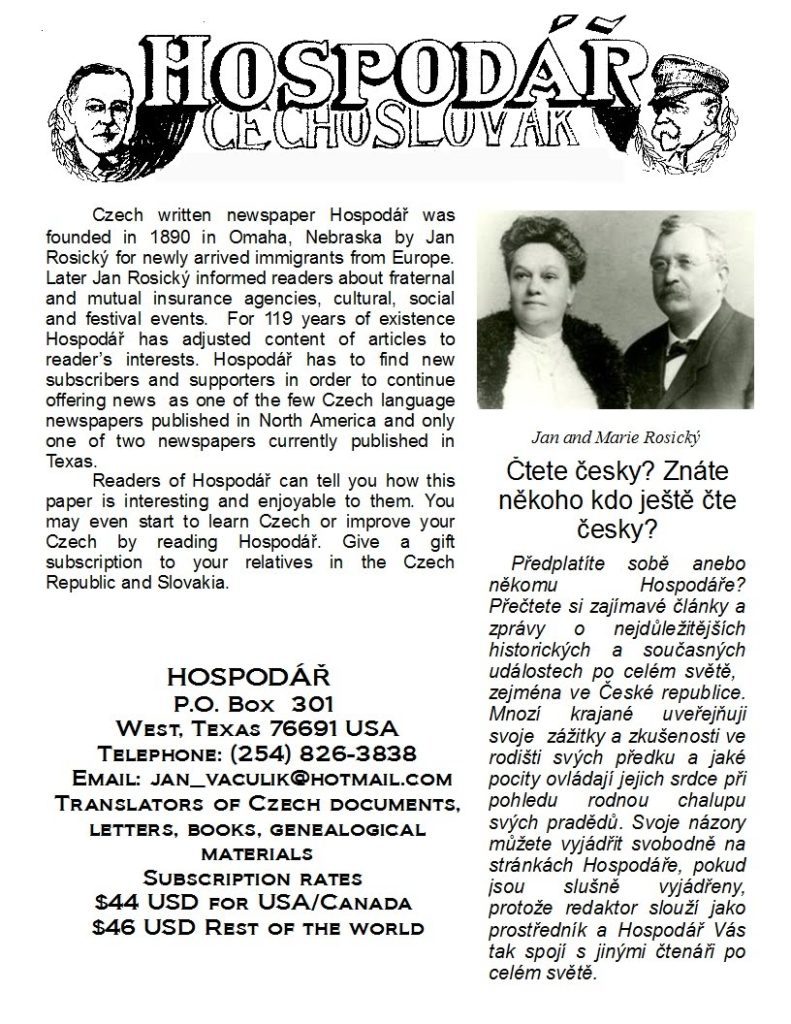

Thomas Capek in his book, The Cechs in America says: “The roster of pioneers would be incomplete without the name of John Rosicky of Omaha. A self-made man, Rosicky came to be recognized as one of the forceful members of the journalistic profession. In 1877 he took over from Edward Rosewater the weekly Pokrok Zapadu (Progress of the West), then a small sheet, without influence and without readers. In time Rosicky raised the Pokrok Zapadu to the front of Cech weeklies. That his tastes were higher than mere commercial journalism he proved in 1884, when he set up the Kvety Americke, the first genuine attempt at a Cech literary periodical. Bravely the Kvety Americke strove to live up to the programme outlined in the prospectus of the publisher. But the most ambitious plans of a publisher are doomed to miscarry, if the reading community fails adequately to support him. Tiring of recurring deficits, Rosicky was forced to modify his original plan with the Kvety Americke. Out of the compromise emerged in 1903 a publication called Osveta Americka (American Enlightenment), half commercial, half literary. By far the most profitable of Rosicky’s ventures proved to be an agricultural paper, the Hospodar (The Farmer).

This publication now claims a larger circulation than any other agricultural paper printed in the Cech language. Rosicky was a newspaper man and not an author, although he published his translation of the Nebraska School Laws and a brief booklet, businesslike and to the point ‘Jak je v Americe’ (Conditions in America) for the guidance of newly-arrived compatriots in America. A man of compelling individuality, he rendered helpful service to the settlers west of the Missouri river.”

So what do we know about Rose’s father, Jan Rosicky?

Jan Rosický was born on 17 December 1845 in the town of Humpolec, Czech Republic, to averagely wealthy parents. Since elementary school, which he attended in Humpolec, he showed keen abilities, his father allowed him to go and study in Prague, where he stayed for two years. Unfortunately, his father’s financial circumstances had changed so much that they did not allow the promising young man to continue his studies so he returned home to his parents.

When he was 16-years-old, he and his uncle (his father’s brother) went to America, arriving in the spring of 1861. Soon his parents came to visit him, too, and they were able to purchase a small farm in Grant County, Wisconsin. Jan spent nearly four years working hard with his parents at the farm. After that, he went to Milwaukee for 6 months and thereafter to Chicago because he wanted to experience a wider field in which to find work. When he first arrived in Chicago, he got a job in a flour and forage shop, and shortly afterwards he set up a separate grocery shop, from which he also ran a canal and insurance business.

In Chicago and as a member of Sokol of Slavonic Lipa and Glagolitic, Rosicky participated diligently in all the Czech and national movements of that time. He was also a gifted and tireless amateur writer. From this period we can see the first beginnings of his journalistic activity date; he was a regular correspondent to the Racine paper, Slavia and to the Národné noviny in St. Louis, and when these latter were later moved to Chicago, he became their co-editor.

In a terrible fire in 1871, which destroyed much of Chicago, Jan Rosicky, like a hundred other compatriots, lost all of his possessions. It upset him to the extent that he fled and went all the way to the Pacific coast. He spent some time in California and Oregon and after two years he settled in Crete, Nebraska in the spring of 1873, where he set up a grocery store.

From his travels to the West and Northwest, Rosicky diligently wrote letters to the weekly Pokrok Západu, which was founded in 1871 by the late Ed. Rosewater. These letters were of great interest to both the publisher and all the readers, as they seemed to reveal the writer’s keen observational talent.

When, in 1876, the current editor of Pokrok Západu resigned his seat, Jan Rosický became his successor. In 1900, Pokrok Západu became a part of the Pokrok Publishing Company. However, Rosicky was not satisfied with the publication of only one magazine. His efforts carried on further. In 1884 he founded the magazine Květy Americké, but their publishing stopped after three years, because it was not financially successful. Later he founded Knihovnu Americkou, but it also did not last long. It was the same sad fate also met by Květy Americké. In 1900, Rosicky became associated with Osvěta, which Rosicky bought from S. L. Kostohryze and he gave it a new name, Osvěta Americká.

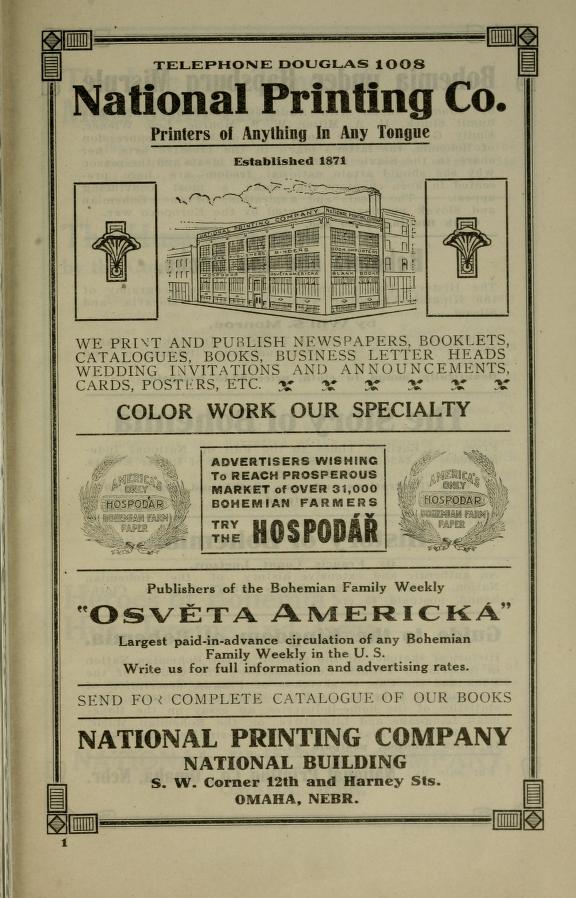

Certainly, Jan Rosický’s most important and largest journalistic enterprise is and will remain Hospodář, a fortnightly devoted to the interests of Czech-American farmers. This magazine was founded by Rosicky in March of 1890 and it is believed that he never dreamed of how much success he would achieve with that publication. Rosicky had another warm desire in his heart which he wanted to see realized. He intended to build his own building for the purpose of the printing and publishing of his papers where he would be chairman and director. He accomplished this goal. John G. Rosicky, president of the National Printing Company and president of the National Building Company, had as the basis of his business advancement thorough educational training, supplemented by laudable ambition and unfaltering determination.

The building was built on a valuable piece of land in the commercial center of Omaha, on the S.S. corner of 12th and Harney Streets.

Jan Rosický also took part in civic and community activities. He was one of the oldest members of Gymnasium Jednota Sokol in Omaha. He was a co-founder of the Mystery Czech-Brethren Union, whose body he managed since its foundation. He was an ardent member of the Free Community of which he was a speaker, and he also belonged to the Association for Cremation (the Burning of the Dead). As a citizen he was counted among the foremost men of the city of Omaha, and indeed the entire State of Nebraska, in whose installation he did a tremendous job. Ústřední Matice Školská (The Central School) in Prague, česká Útulna and the Chicago Orphanage lost a warm friend and enthusiastic supporter when Jan Rosický passed away.

But the greatest credit given to Jan Rosický must surely be for establishing and implementing the Czech-American Press Office, for if it hadn’t been for him, it would never have been a national (and very important) undertaking. In recognition of the merits of those elected, Rosicky was also its first chairman. As you can see, the Rosický’s of Omaha are among our most notable Czechs.

As for his private life and family circumstances, it should be noted that the family of Jan Rosický was one of the happiest and most coziest Czech families in Omaha. Rosicky proved himself to be a careful father and exemplary husband. Rosicky met his wife Mary (born Marie Bayerova in Klatovy in 1954) during his first stay in Chicago. Their we wed in Omaha in 1874.

Mrs. Rosická described her first experience in America in an issue of Hospodář. She wrote, “After my father’s death, I came to this country in 1869, namely to my uncle who lived in Louisiana, Mo. And my uncle acknowledged the first thing I needed to learn was English, which he said was best learned through labor. I went to work on a farm that had slaves, not far from Louisiana. The workers on the farm were mostly blacks, the cooks too, and I got to know southern life. My uncle negotiated my salary for 50 cents a month. I cried and was so excited at that time! I was there for a whole year and I saved $5.” Mary continued, “For two years I served in a cafeteria in the Machov area in St. Louis, and I arrived in Chicago in 1871 where I met my future husband.”

The Rosicky couple had a total of eight children, of which four survived to adulthood. They were: John, who was married and occupied a favorable position with the Nebraska Telephone Company in Omaha; Ladislav, employed in the work of his father, Rose, active as her father’s secretary and then taking over much of his work after he died, and Emma, a teacher at the public schools in Omaha.

John Rosický attended work for the last time on Saturday, December 4, 1909. At that time, he still seemed to be completely healthy and at full strength. However, when he arrived at his home residence at 1015 William Street, he fell ill with symptoms so severe that members of his family considered it appropriate to call the doctor immediately, who noted the patient had developed brain inflammation. From this horrible diagnosis, however, John soon woke up, and it appeared that there was a chance of permanent recovery. He also appeared to have a complete clarification of the mind, and everyone believed he the terrible illness would pass. But this was not to happen. A tumor began to form and John Rosicky died prematurely.

The news of his death caused widespread commotion everywhere because everyone had hoped for his full recovery. Mr. Rosicky remained an active factor in the publication of these papers until his death, which occurred April 2, 1910. The funeral of Jan Rosický took place on Tuesday, April 5, 1910, from the “Sokol Omaha” building on 13th Street with a huge participation of friends and acquaintances of the deceased at the Czech National Cemetery in Omaha. After the relevant ceremonies in the Sokol Hall, which had been mournfully decorated, the coffin and the deceased were lifted and inserted into the hearse so that all the flowers and wreaths would be deposited in the womb of the earth at the aforementioned cemetery.

His widow survived until August 15, 1912, when she, too, passed away in Omaha.

Rose’s parents, no doubt, had a profound influence on her life and her life’s work.

The Rosický’s I’ve written about today have died and were buried, but the memory of their merits will not disappear. Among those deserving Czechs whose names grew with the history of the Czechs in America, the names of Jan Rosický, Marie Rosický and Rose Rosický will always be found in some of the leading places.

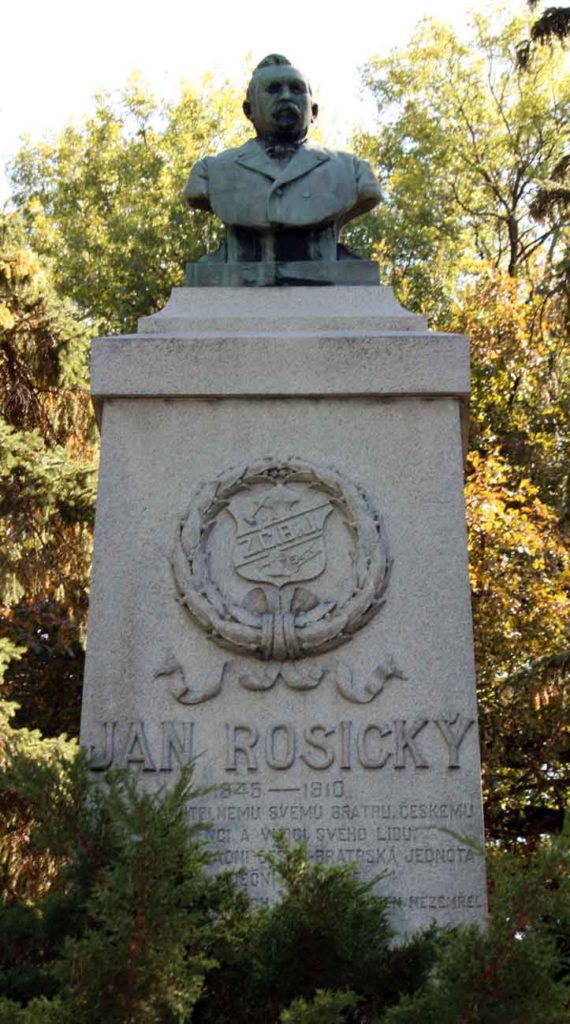

As you drive into the Bohemian Cemetery in Omaha, Nebraska, the first monument that you see is the John G. “Jan” Rosicky memorial.

The Bohemian Cemetery is located at 5201 Center St, Omaha, NE 68106 .

Ending Notes

Beginning on August 1, 1871, Pokrok Západu, or “Progress of the West” was published as a weekly Czech-language newspaper in Omaha, Nebraska, by the well-known publisher and editor of the Omaha Daily Bee, Edward Rosewater (1841-1906). Born in Bohemia, Rosewater immigrated to the United States in 1854. Known for his feisty temper, Rosewater aggressively espoused in his papers Republican Party views on issues such as slavery and immigration. The success of Pokrok Západu was immediate, in part because one in five immigrants of Czech descent lived in Omaha and other Nebraska communities. Sold at $1.00 per week, the paper often included works of fiction and poetry, articles on farming, reminiscences of the Old Country, as well as news of the day. Pokrok Západu was a large format paper at 15″ x 22″ and had a circulation of 20,000 by 1880.

In March 1876, Jan Rosický (1845-1910), also originally from Bohemia, became the editor of the paper, purchasing it from Rosewater in 1877. Previously, Rosická had edited the Hospodář (“Farmer”), an important agricultural magazine that encouraged Czechs to immigrate to the United States. Under his leadership, the Pokrok Publishing Company was formed, and gradually Pokrok Západu became an important regional newspaper for Czech communities in Nebraska, Kansas, Minnesota, Iowa, and the Dakotas. In the years that followed, the Pokrok Publishing Company produced various local editions of the newspaper. They included: Creteský Pokrok (Omaha & Crete, Nebraska), or “Progress of Crete,” 1905-19??; Pokrok (Clarkson, Schuyler & Omaha, Nebraska), or “Progress,” 1903-20; Kansaský Pokrok (Wilson, Kansas), or “Progress of Kansas,” ;19??- 20; Iowský Pokrok (Cedar Rapids, Iowa), or “Progress of Iowa,” 1906-19??; Minnesotský Pokrok (Minneapolis, St. Paul & Omaha), or “Progress of Minnesota,” 1908-20 (formerly St. Paul’s Minnesotský Noviny, or “Minnesota Newspaper,” 1904-19??); and, finally, Dakotský Pokrok (Tindall, South Dakota), or “Progress of the Dakotas,” 19??-19?? Source: Library of Congress.

Willa Cather, celebrated author of the book My Antonia wrote to Rose Rosicky in 1933. We’re the noted source of that letter and you can read it in our post entitled, Willa Cather and Her Love of Czechs.

Following Jan Rosický’s death in 1910, the publishing enterprise continued under the direction of his daughter, Rose Rosický (1875-1954). Pokrok Západu and its extant local editions were finally absorbed into Chicago’s Hlasatel, or “Newsreader,” in 1920. Rose Rosický later published A History of Czechs in Nebraska in which she praised her father as a pioneer and leading newspaperman of his day.

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Thank you in advance!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

Very enjoyable and informative reading.

Rose was my Great- Great-Aunt and Jan my Great- Great Grandfather. My grandmother was Dorothy Rosicky (Smith by marriage). It is SO great seeing their legacy online. Thank you for what you do!