As we commemorate the 100th anniversary of the independence of Czechs and Slovaks from the Austro-Hungarian oppression and the foundation of Czechoslovakia on October 28, 1918, we should also remember the role the Czech Americans played on behalf of their homeland. This is why we are thankful to guest author Miloslav Rechcígl, Jr. for his article we are sharing here today entitled, Czech America in the Struggle for Independent Czechoslovakia.

The liberation movement for an independent Czechoslovak state had its beginnings since the earliest days of World War I. On July 7, 1914, a rally took place in Pilsen Park by the Chicago Czechs to voice their sympathy for the Serbian brothers who were attacked by the Austro-Hungarian forces. The organizer of the meeting, Jaroslav Nigrin, proclaimed on that occasion that the war would lead to the defeat and eventual breakup of Austro-Hungarian rule and that American Czechs should get ready for such eventuality. What prophetic words these were.

A day later, another meeting was convened in Chicago, this time in a spacious hail which was filled to capacity. This meeting, chaired by J. F. Štěpina, ended with a spontaneous demonstration resulting in tearing down an insignia, which the demonstrators mistook for the symbol of Austro-Hungarian monarchy, from the wall.

Angry Czechs trampled over it with excitement and this act was duly reported in great depth in major newspapers throughout the country. From this point on Czech Americans became openly defiant against the Austrian state. Similar demonstrations followed in other major Czech centers throughout the US.

Early on, Czech Americans realized the need for a unified organization in order to cope with the concerted efforts of American German propaganda to influence public opinion for their cause. In those days German propaganda was so effective that one might get the impression that the American press was entirely pro-German.

But thanks to the efforts of three Czech American organizations, German lies, and fallacies began to be systematically challenged and refitted. One of these organizations was the Czech American Press Bureau (“Česká Americká Tisková Kancelář)”, under the leadership of Francis Korbel. Another was the Czech-American National Council (“Česko-Americká Národní Rada”), founded in Chicago in 1910 by E. S. Vráz, and the third was the Czechoslovak Relief Council (“Československý Pomocný Výbor”), which led to the Czechoslovak Red Cross.

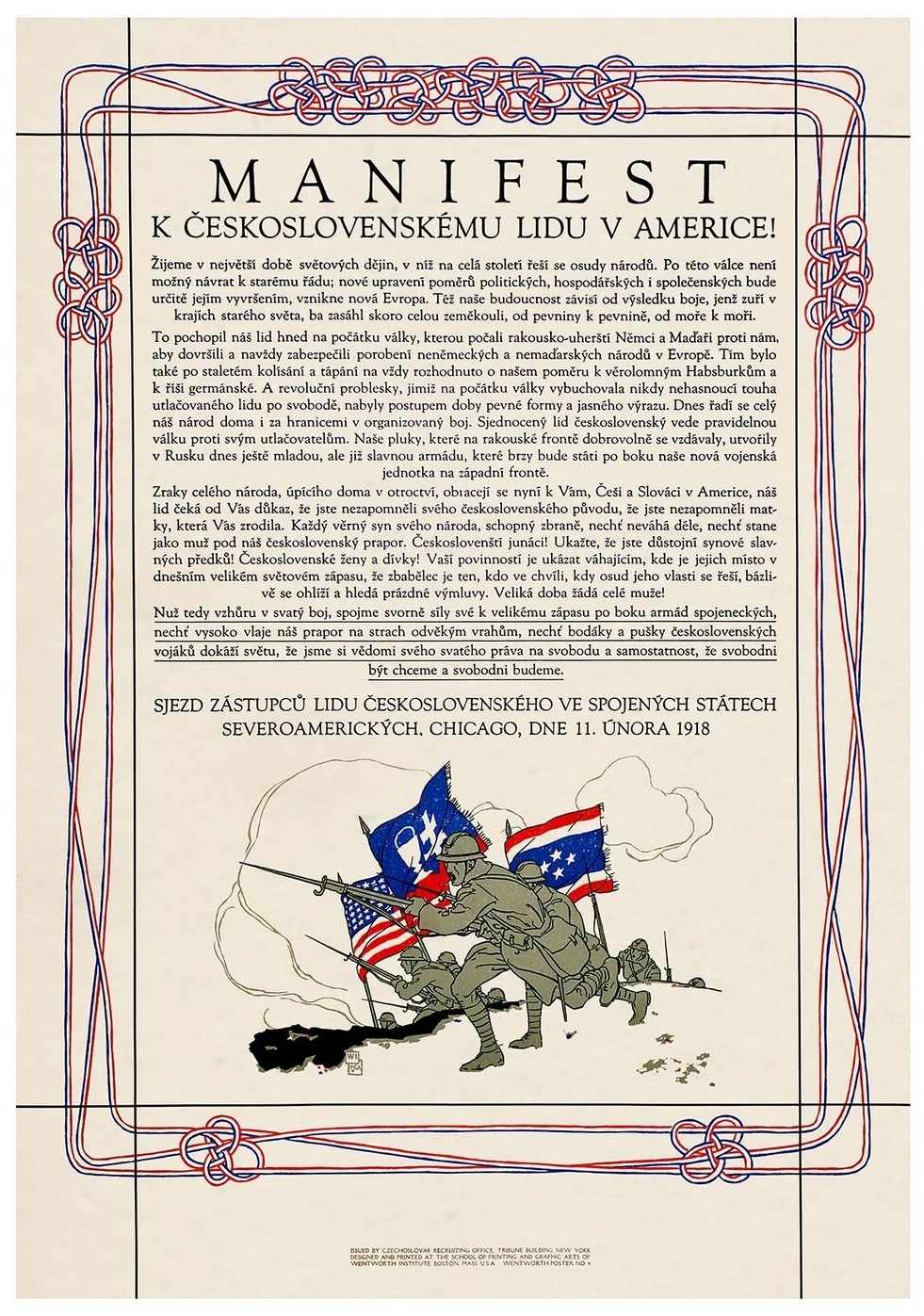

On August 29, 1914, the Czech American Press Bureau delivered, in the name of all Czech newspapers in America, a special manifest to President Woodrow Wilson, as an answer to his plea for neutrality. In this manifest the Czechs vehemently protested against Austria sending Slav soldiers against their Slav brothers.

These three organizations were the predecessors of the Bohemian National Alliance which was officially established on September 6, 1914. At the beginning of October of the same year, the Slovak League issued a separate memorandum, signed by Albert Mamatey, which expressed the idea of uniting Czech and Slovak liberation efforts in the interest of establishing an independent Czechoslovak state.

Following the Austrian declaration of war against Serbia, there was rapid change in public opinion, as it was among the ranks of American Czechs, as well as Slovaks. The declaration led to the formation of numerous relief organizations to assist orphans and widows, and collection drives began in earnest. From this spontaneous movement came the future Czech American leaders, such as the physician L. J. Fisher from Chicago, the businessman Emanuel Voska from New York, the banker James F. Štěpina of Chicago, C. B. Svoboda from Cedar Rapids, and Prof J. J. Zmrhal from Chicago. They met in Cleveland in the spring of 1915 to draw plans for unified action against the Austro-Hungarian yoke. This was also the group of individuals to whom Thomas G. Masaryk appealed for help during his stay in London.

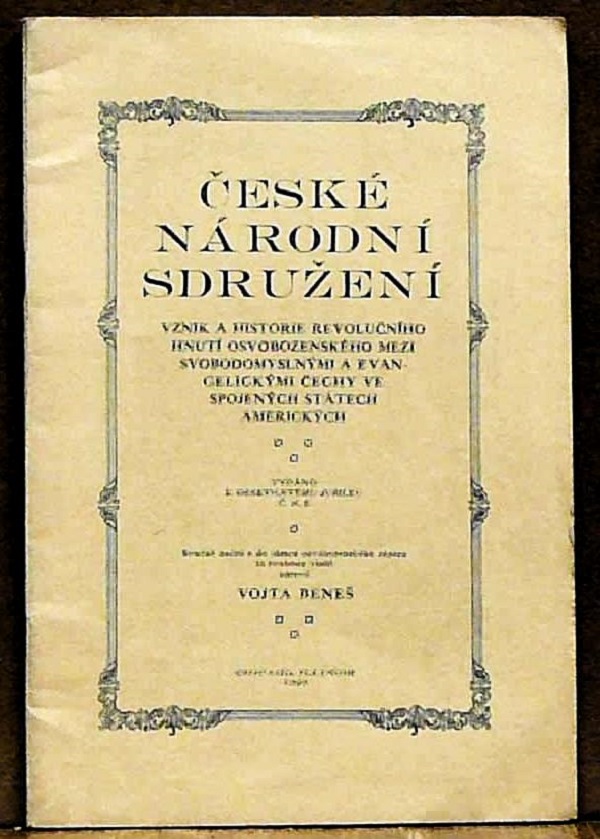

This was the beginning of the Bohemian (later Czech) National Alliance in America (“České Národní Sdružení”) which led a victorious fight against Austro-Hungary in the US.

Czech Chicago was in the center of this liberation movement, together with the help of various Alliance’s branches, e.g., New York, Detroit and Omaha. Under the leadership of Dr. Fisher, who became the chairman, and Josef Tvrzický, the executive secretary, the number of these branches throughout the US eventually grew to 350.

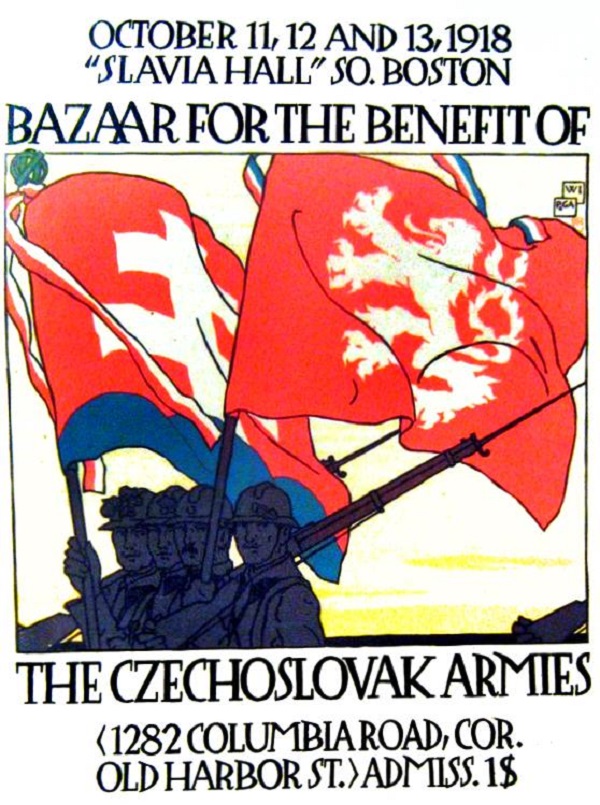

Money was the first priority. At Masaryk’s request, not even a single dollar was to come from foreign sources. “This is our revolution and we must pay for it with our own money”, declared Masaryk. In the winter of 1916, the first large bazaar was held in New York which brought a total of $22,250, a rather large sum in those days. The second bazaar was organized in Cleveland in March 1917 which brought in $25,000, followed by the Chicago bazaar which netted $40,000. A relatively small Omaha community came in with the incredible amount of $ 65,000 in September 1918, and a few weeks later, the Czech Texans brought in another $60,000. On Thanksgiving Day, the national campaign brought in a total of $ 320,000 which was later increased by an additional $ 100,000 and $ 40,000, from Chicago and Cleveland, respectively.

The collected funds were, of course, not intended solely for political purposes. A large sum of money was used to ease the suffering of our people overseas. Thus, one million francs were sent to the Czechoslovak Minister of Foreign affairs in Paris for the purchase of food.

The actual total sum collected by the Czech Americans is not known, since a considerable part of the money came from the gifts of individuals. Some estimates run in millions of dollars. What is certain, however, is the fact that the American financial support must have played a significant, if not crucial, role in the struggle of Czechs for their independence, because otherwise it would not have been possible to finance the liberation efforts abroad.

Because of the American neutrality, the first Czech liberation efforts were carried out in moderation and with some restrain, focusing primarily on informing the American public about the Czech or Czechoslovak cause. Once the US declared war, all their inhibitions were gone. The first step was the establishment of a new press office, known as the Slav Press Bureau, located in New York City.

There were numerous mass meetings and public debates, as well as lectures to which prominent scholars and men of affairs were invited from Europe, particularly from the Czechlands. New newspapers and magazines were established and numerous propaganda pamphlets and leaflets in a variety of languages were issued and distributed. Among the most effective newspapers, one needs to particularly mention the Chicago based Svornost. In February 1916, the Bohemian National Alliance started publishing the Bohemian Review, which since November 1917 appeared under the new title, Czechoslovak Review. The original Slav Press Bureau eventually was renamed the Czechoslovak Information Bureau and based in Washington, DC.

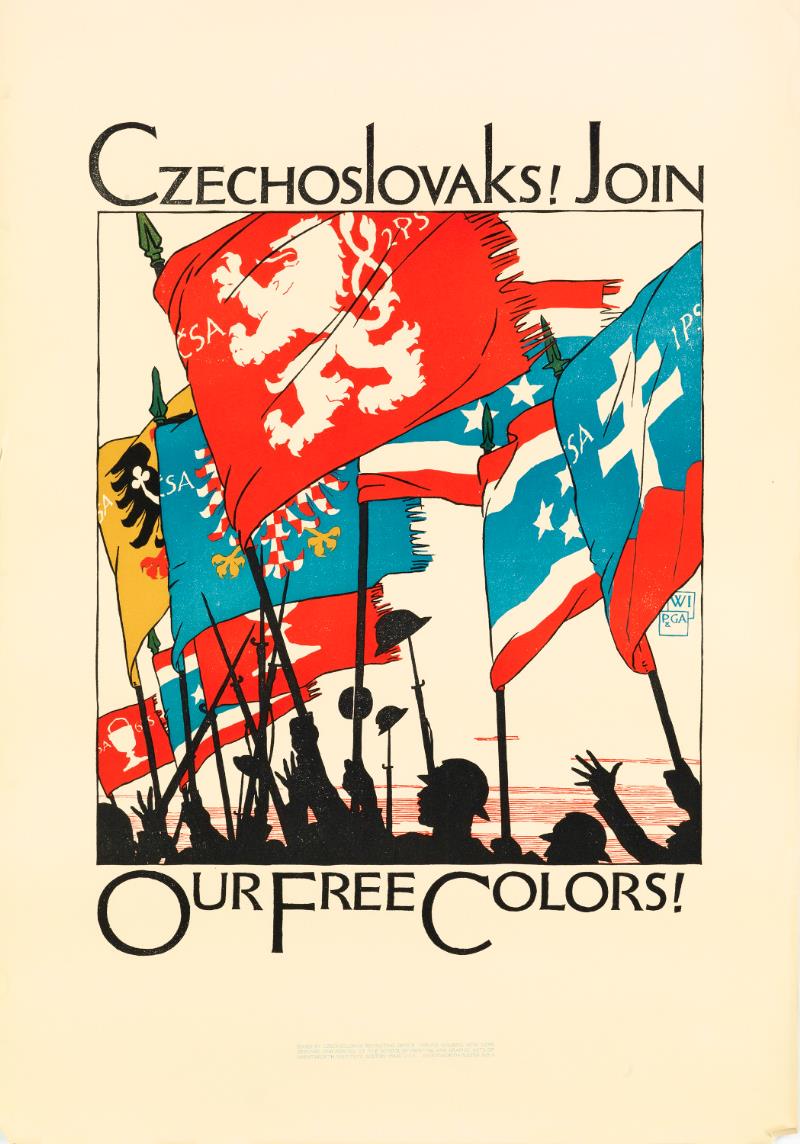

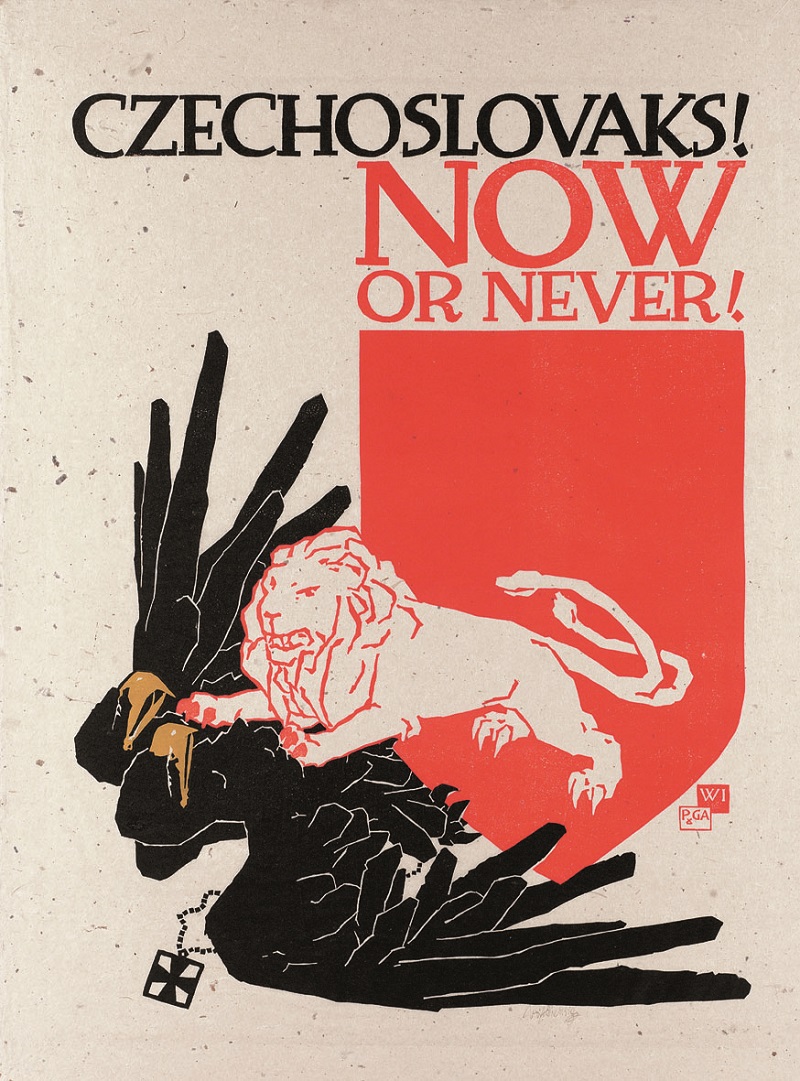

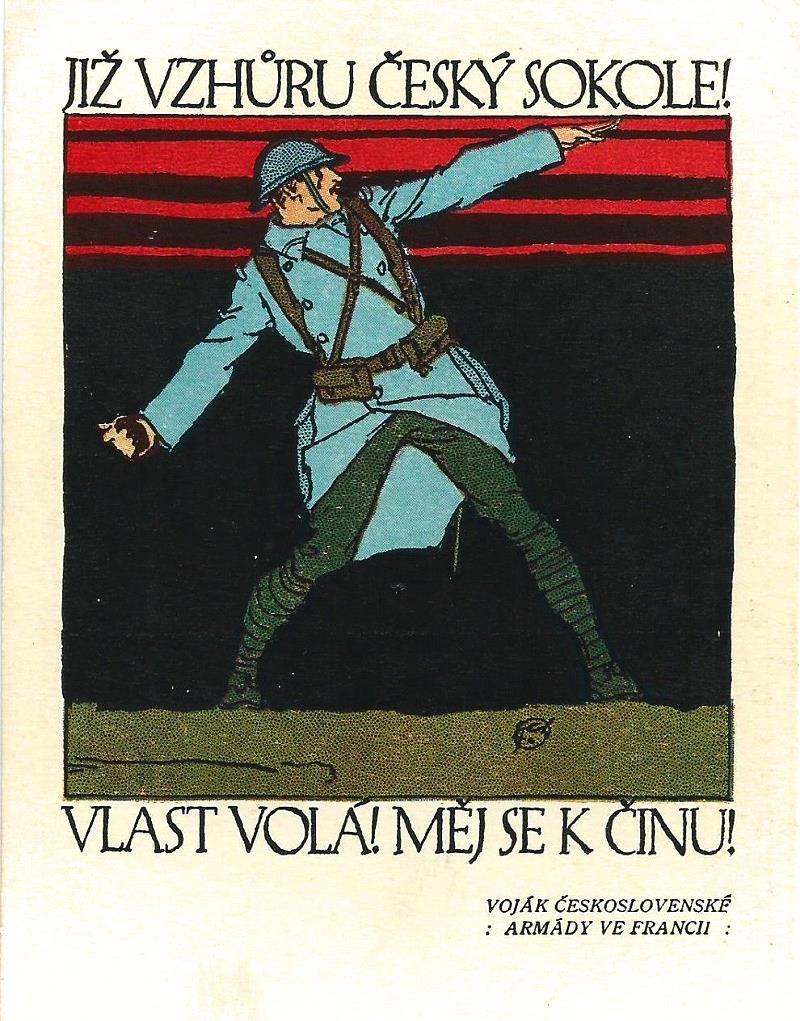

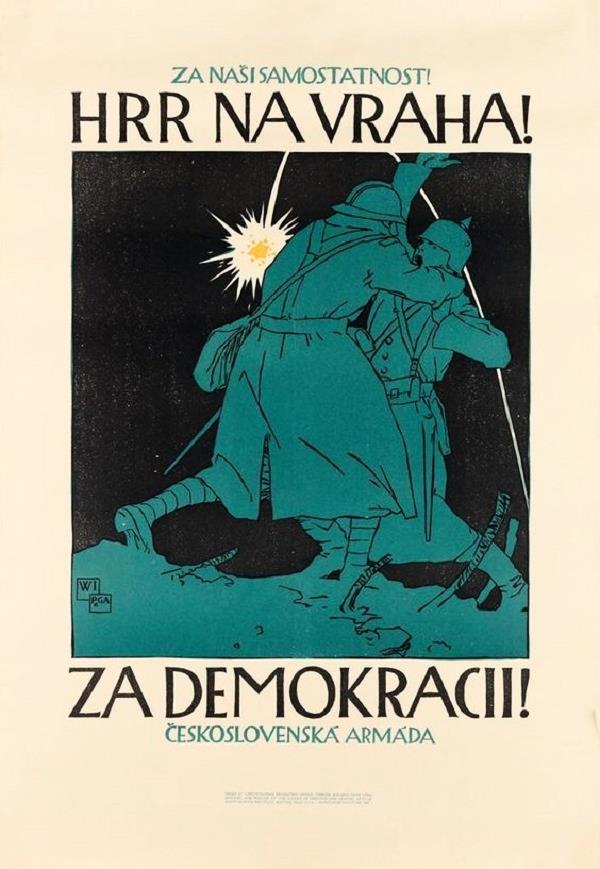

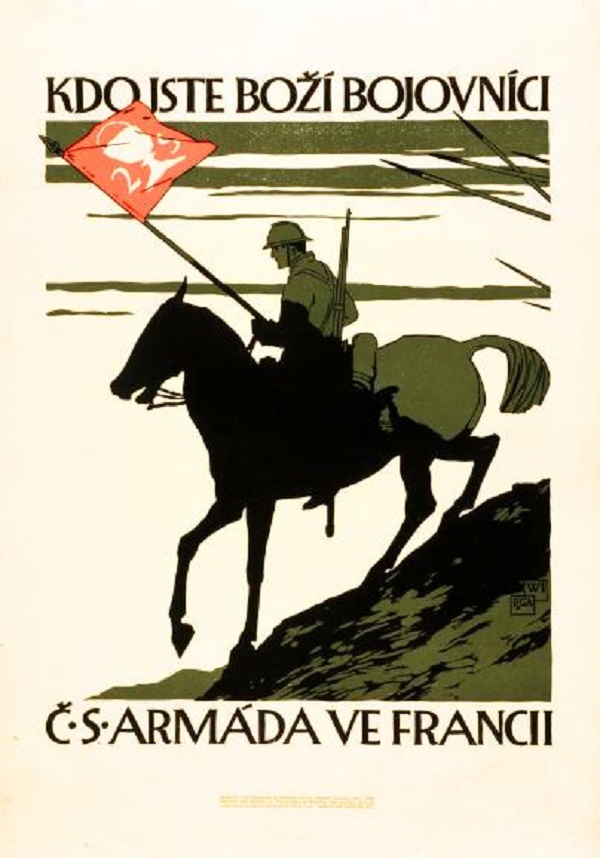

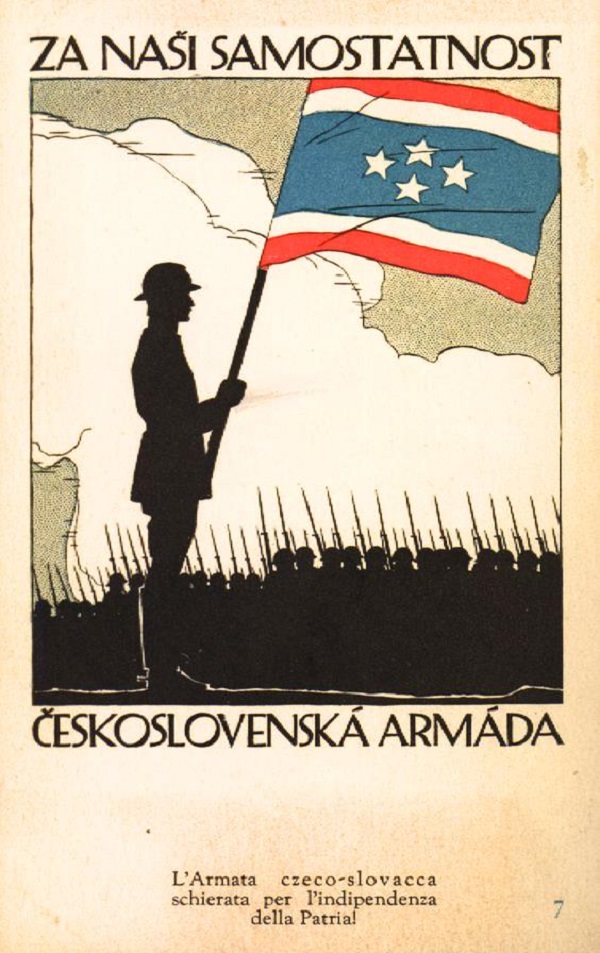

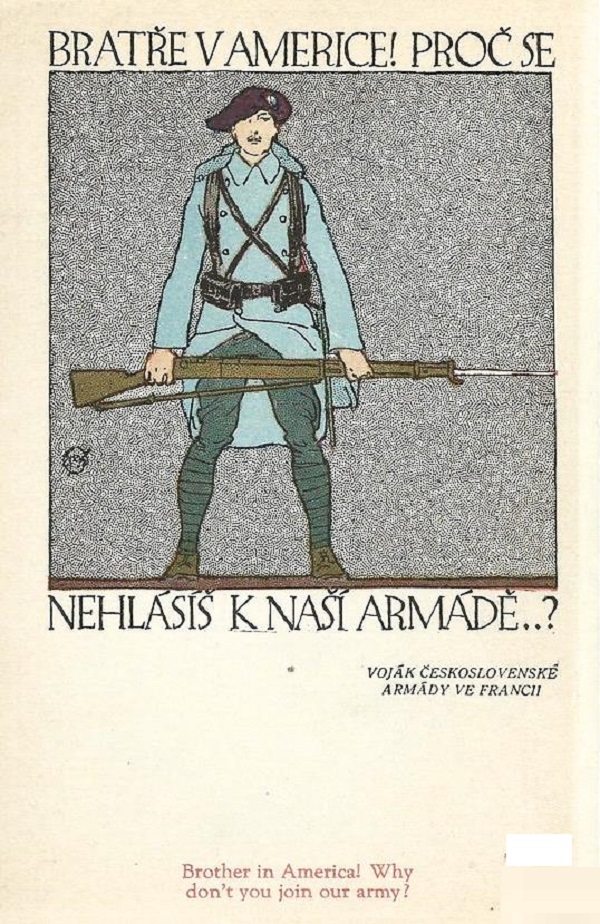

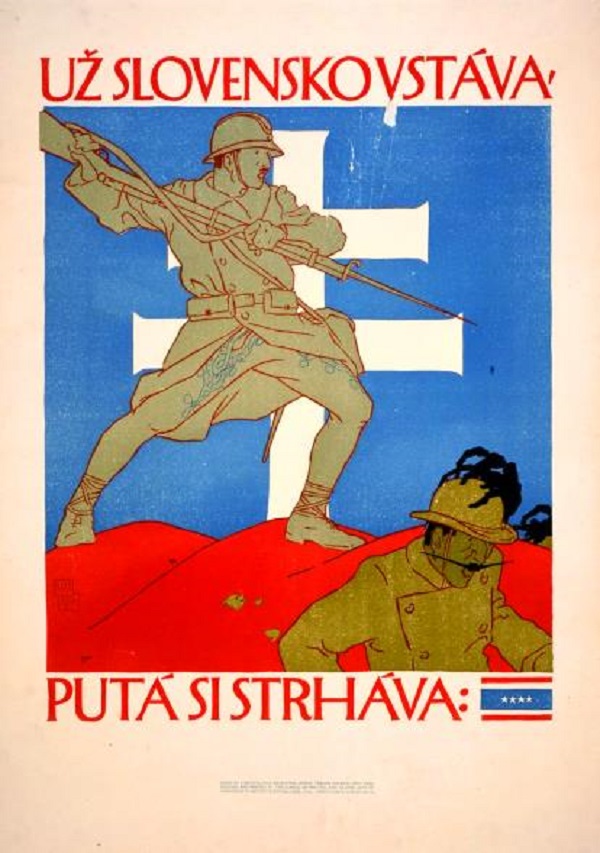

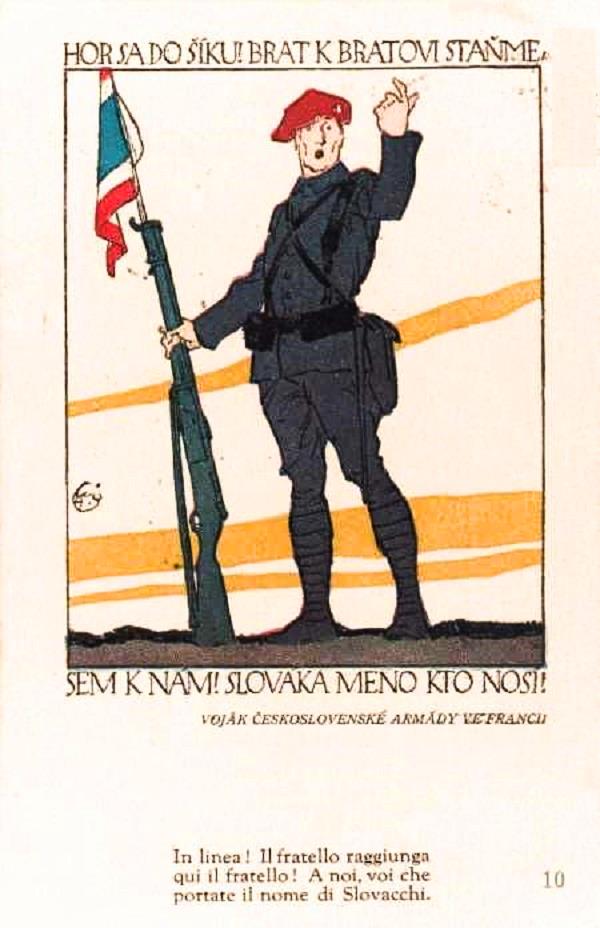

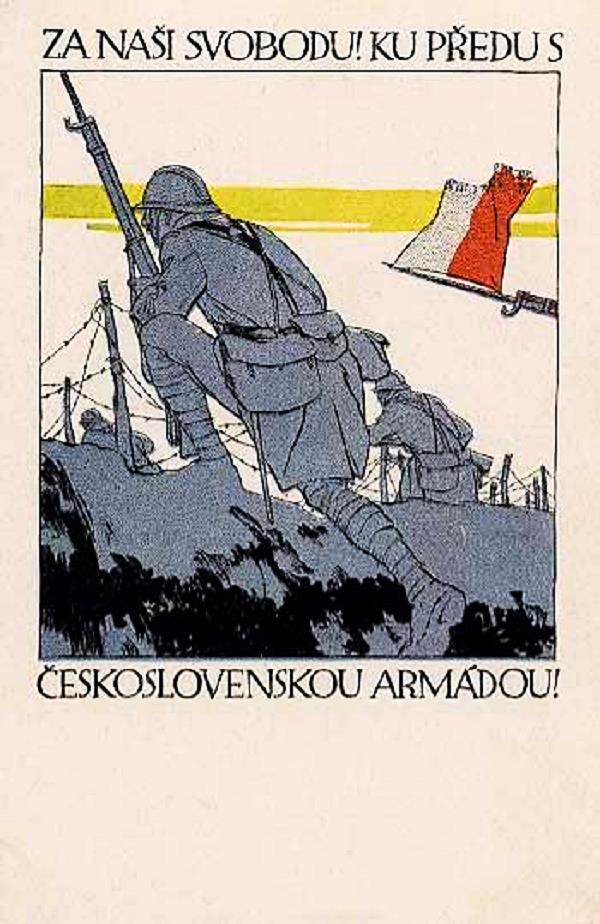

As discussed in detail in Thomas Čapek’s classic book, The Čechs (Bohemians) in America, attractive postcards and artistic stamps were put into circulation, and buttons and badges sold for the benefit of the campaign. The prominent Czech American artist Vojtěch Preissig designed masterful war posters. The Czechoslovak Arts Club of New York in an artistic manner decorated the show windows of prominent business houses on Fifth Avenue with Czechoslovak colors, views, portraits, maps and posters. The most dramatic exhibit was a huge map of Central Europe, showing the boundaries of the new reborn state, and marked the strategic position of the Czechoslovak troops astride the Trans-Siberian railroad in Russia. Thousands of New Yorkers were compelled to take notice of the map which was strategically placed on the most conspicuous place in front of the Public Library, at the corner of Fifth Avenue and Forty-Second Street.

After the US declared war on Germany and General Milan R. Štefánik came to the US to organize recruitment of Czechoslovak army, 50,000 young men of Czech descent volunteered their services. When the question arose how to best help the Czech lads on the French front or in Siberia, Czech women in America painstakingly knitted, washed laundry, and provided tobacco, needles, thread, soap – simply everything our soldiers needed. They also took care of the lonesome and desolate Czech families in the US, frequently visiting them and helping them with their children.

This was done under the auspices of the newly established Czechoslovak National Council (“Československá národní rada”), of which Professor Bohumil Šimek of Iowa served as President, and Albert Mamatey and Father Innocent Kestl, Vice Presidents. Under this new arrangement, the Czech National Alliance shared its work with the Slovak League and the National Alliance of Czech Catholics (“Náodní Svaz Českých Katolíků”). One person, who almost singlehandedly was responsible for the unity between previously adverse parts of the Czecho-Slovak community, i.e. Catholics vs. non-Catholics, as well as Czechs vs. Slovaks, was Father Oldřich Zlámal of Cleveland. Another person deserving mention on behalf of the Czechoslovak cause was Charles Pergler, who was entrusted with the publicity and diplomatic aspects of the joint liberation effort, until the time the Czechoslovak state was proclaimed, following which he was appointed the Czechoslovak representative in the US.

We must underscore the important role the Czech and Slovak women played in the liberation movement. They formed their own organizations, “Včelky” and “Priadky,” respectively, whose total number around the US exceeded 200 . The clothes, hosiery and other material they produced and the countless parcels they sent overseas were way beyond three million dollars in value.

The pivotal event of the Czecho-Slovak America was the arrival of Thomas Garrigue Masaryk in the US in April 1918 on his return from Russia. The rally in Chicago was attended by more than a quarter of million people, who welcomed him “with tears in their eyes and pride in their heart”, as was somewhere written. Similar welcome awaited him in New York and Cleveland. The whole America was at awe who this man is who is applauded by hundreds of thousands American citizens. From that point on the American press wrote regularly about the Czech and Czechoslovak cause.

Czech Americans did their part and we salute them for it!

Notes:

Literature about the struggle of the Czech Americans for the independence of the Czech Nation is extensive, yet it is becoming forgotten. Here are some of the most important publications: Thomas Čapek, “The Part the American Čechs Took in the War of Liberation,” in: The Čechs (Bohemians) in America. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., pp. 265-278; Josef Buňata, Památník texaských Čechoslováků na práci vykonanou v letech 1914-192 ve prospěch osvobození vlasti starých. Ennis, TX: Krajský výbor ČNS pro Texas a Lousianu, ca 1921; Vojta Beneš, Revoluční hnutí v Severní Americe. Praha: Nákladem Památníku odboje, 1923; Emil Tůma, “Vděk československé Americe,” Naše zahraničí 4 (1923), pp. 55-59; Lev Sychrava a Jaroslav Werstadt, Československý odboj. Státní nakladatelství, 1923; František Šindelář, Z boje za svobodu otčiny. Chicago: Národní svaz českých katolíků, 1924; Em. V. Voska, Československá Amerika v revoluci. Praha: Nákladem Památníku odboje, 1924; Otto Traub, “Českožidovské hnutí a jeho vliv při odboji České Ameriky proti Rakousku,” Kalendář česko-židovský 57. Prague, 1925, p. 144ff.; Tomáš Čapek, “Odboj,” in: Naše Amerika. Praha: Národní rada československá, 1926, pp. 457-480; Charles Pergler, America in the Struggle for Czechoslovak Independence. Philadelphia: Dorrance & Co., 1926; Joseph Chada, “Czech-American Aid to Czechoslovak Freedom, July 1914-December 1917,” in: The Czechs in the United Sates. SVU Press, 1981, pp. 43-53; Joseph Chada, “Czech-American Aid to Czechoslovak Freedom, 1917-1918, in: The Czechs in the United Sates, op. cit., pp. 55-68; Bruce Garver, “Americans of Czech and Slovak Ancestry in the History of Czechoslovakia,” Czechoslovak and Central European Journal 11, No. 2 (Winter 1993), pp. 1-14; Rechcigl, Miloslav, Jr., “Czech America in the Struggle for Independent Czechoslovakia,” in: Czechs and Slovaks in America. Boulder, CO: East European Monographs, 2005, pp. 207-210.

Guest Post Author

Miloslav Rechcígl, Jr. is one of the founders and past Presidents of many years of the Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences (SVU), an international professional organization based in Washington, DC. He is a native of Mladá Boleslav, Czechoslovakia, who has lived in the US since 1950.

Read his entire profile here. Discover Mila’s many books on Amazon.

Thank you for your support – We appreciate you more than you know!

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Thank you in advance!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

I learn so much at your site. Keep this information coming.

Excellent article.