Today we are looking at Martha Gellhorn’s report on Czechoslovakia in 1938. Martha Ellis Gellhorn (November 8, 1908 – February 15, 1998) was an American novelist, travel writer, and journalist who is considered one of the great war correspondents of the 20th century. She reported on virtually every major world conflict that took place during her 60-year career. Gellhorn was also the third wife of American novelist Ernest Hemingway, from 1940 to 1945.

Ernest Hemingway and Martha Gellhorn

Gellhorn first met Ernest Hemingway during a 1936 Christmas family trip to Key West, Florida. They agreed to travel to Spain together to cover the Spanish Civil War, where Gellhorn had been hired to report for Collier’s Weekly. The pair celebrated Christmas of 1937 together in Barcelona.

Later, from Germany, she reported on the rise of Adolf Hitler. In the spring of 1938 (months before the Munich Agreement), she was in Czechoslovakia.

After the outbreak of World War II, she described these events in the novel A Stricken Field (1940). She later reported the war from Finland, Hong Kong, Burma, Singapore, and England. Lacking official press credentials to witness the Normandy landings, she hid in a hospital ship bathroom, and upon landing impersonated a stretcher bearer; she later recalled, “I followed the war wherever I could reach it.”

She was the only woman to land at Normandy on D-Day on June 6, 1944. She was also among the first journalists to report from Dachau concentration camp after it was liberated by US troops on April 29, 1945.

She died in 1998 in an apparent suicide at the age of 89, ill and almost completely blind.

The 2012 film Hemingway & Gellhorn is based on these years. The 2011 documentary film No Job for a Woman: The Women Who Fought to Report WWII features Martha Gellhorn and how she changed war reporting.

Today I am sharing an article from Collier’s Magazine written by Martha Gellhorn and published on August 6, 1938.

Collier’s was an American magazine, founded in 1888 by Peter Fenelon Collier. It was initially launched as Collier’s Once a Week, then changed in 1895 to Collier’s Weekly: An Illustrated Journal, and finally shortened in 1905 to simply Collier’s.

The magazine ceased publication with the issue dated for the week ending January 4, 1957, though a brief, failed attempt was made to revive the Collier’s name with a new magazine in 2012.

As a result of Peter Collier’s pioneering investigative journalism, Collier’s established a reputation as a proponent of social reform.

Her writing gives interesting insight to the history of Czechoslovakia at the time.

Come Ahead, Adolf!

It is Sunday morning, and from the Castle Hill you can see the sharp elaborate church spires of Prague rising above the dark roofs of the city. Down there in the main street, President Benes stands bareheaded in the sun, in a flag-bright box, watching the Social Democrats of Czechoslovakia parade past. They come down the wide avenue, for four long hours, twelve abreast, with floats and bands, and they march in perfect time, in perfect order. It is very decorative and very gay.

The Bakers’ Union marches with giant breakfast rolls on their heads, the Slovak peasants in embroidered blouses and red skirts and high boots dance past, the Boy Scouts cook a meal and dodge the smoke from their campfire on a truck masquerading as a forest. They sing and cheer and salute the crowd and the president. All the banners and signs repeat the word: Democracy. They talk a great deal about democracy in Czechoslovakia because they think they may have to fight for it. They know that war is waiting about fifty miles away, at the nearest frontier.

You can’t miss it. You can go on a sight-seeing tour, and the guide will stop the bus before the ornate and complicated old clock on the City Hall. “This clock was made in 1490,” he says, “before America was discovered. We were a free nation then, and we are a free nation again, and we will remain a free nation.”

You can go to a wine shop in the evening; the walls will be made of sweet pine wood and there are field flowers on the tables. The place is crowded, and people drink local wine out of squat dark bottles, or the blond beer from Pilsen. The entertainers sing a popular song, and the public joins in the refrain.

The refrain is: “All right, Adolf, come ahead.”

Gas-mask drill for girls between 14 and 17 is part of their training for behind-the-Iines duty in wartime. Here they are emerging from the gas chamber of a truck in which they have tested their masks.

On the frontier between Silesia and Czechoslovakia, the land is open, and behind the town of Troppau little hills like the Ozarks curve around the fields. There are women bending in the beet fields, and men forking the grain. Beside the haystacks are other things that look like haystacks until you get closer and see that they are camouflaged pillboxes, with machine guns and antitank guns in them, and the soldiers stand as quiet as scarecrows among the working peasants. Driving through the pinewoods behind Troppau, near Haj, you see a new fort being built, flat and wide on the top of the hill, and on the road dozens of steel spikes sunk into concrete blocks, from which later the barbed wire will be strung. Then the road dips down from the forest and crosses the river into a plain.

On the other side of that plain is Germany, and across the nearest field is a triple row of barbed wire, on huge spools, and beside the river is a black cement-and-steel gun fortress where, beside machine guns, and antitank guns, there are also the highly perfected antiaircraft guns that all Czechoslovakia believes in. Three soldiers talk to some girls who are drying their hair after swimming in the river.

In the next town—Odersch—you see the Henlein Nazi swastikas and flags in the windows of the small houses, and the Czech soldiers, with the magenta tabs of their regiment on their coat collars, walking quietly about the streets. The fields are warty with pillboxes and black forts—you have seen more than fifty of them in half an hour’s slow ride. If war ever starts, this green and gentle plain will be Flanders. You pass women washing clothes in a soapy canal that borders a village, and there is the frontier again at Wavrovitz. Farm wagons and hayracks, weighted with cement, barricade the frontier road, and you get the authentic, desperate, makeshift feeling of war. . . .

The Czech soldiers who play at war along the German frontier are part of the formidable army of 2,500,000 men that this tiny republic, about the size of Illinois, is prepared to put in the field on short notice

From the Silesian frontier straight across Czechoslovakia to the once Austrian, now German, frontier is about two hours’ driving. The peasants are in the fields, and the villages are empty in the sun. Then you come to Breclav, and a man of sixty with a blue armband stops the car. There is no one else about. He says you must put the car in the shade, by the houses, and wait.

Why?

We are having air-raid practice, he says. It appears that he is one of that great civilian corps, the C.P.O., already organized to take charge of every town and village in the country, in case of attack by air.

Presently a boy comes by on a bicycle, blowing a horn. He rides very fast down the main street and the horn makes a pleasant cool sound. That, the farmer with the armband explains, is the warning. There is not a cat in the street. Ten minutes later the boy comes back, also riding fast, also blowing the horn. That is the all-clear, the man says. It makes me nervous because I remember that it took 95 seconds in Barcelona to wipe out a central chunk of the city and to bury alive several hundred people. Ninety-five seconds is less time than it takes the boy to pedal up the village street. How about bomb cellars, I say; have you any bomb cellars? The old man looks at me—it is a good brown and lined face—and suddenly he says angrily: “No. No. We have no bomb cellars. We do not want bomb cellars. We want quiet and peace.”

And the last village before the Austrian-German frontier is Mikulov. A peasant girl is riding her bicycle to town. She has a short, full skirt of pink flowered material, and a yellow handkerchief on her head; her legs are strong and sunburned and she has a wide red mouth. She looks very pretty against the green fields, with the wind blowing out her skirt. And slung over her shoulder she has a gray cylindrical gas mask.

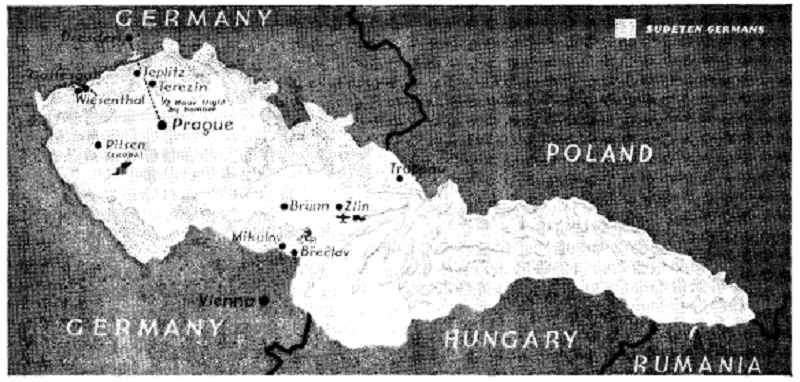

You have seen the German-Czech frontier to the east and west, and now you are going north. Czechoslovakia is shaped like a badly made kite, and its head rests in Germany.

Behind the frontiers that jut into Germany is an elaborate system of pillboxes, fortresses and concrete trenches.

Since Austria was absorbed into Germany, Czechoslovakia is surrounded on three sides by the Reich. When the Allies tried to give back the ancient kingdom of Bohemia to its former inhabitants, after the war, three and a half million Germans who had been Austrian citizens suddenly found themselves Czech citizens.

These Germans live mostly in a band of territory along the German-Czech frontier, and here the German Social Democrats and the Henlein Nazis (all Czech citizens by law) wage a constant and bitter political battle, while the Czechoslovak government—like good democrats—allows each and every party to have its say. Since the Anschluss, (Anschluss refers to the annexation of Austria into Nazi Germany on 12 March 1938.) everyone means business; and any political meeting has a fine chance of ending in a riot, and who knows what a riot may end in?

The German Social Democrats had planned a big meeting in a Henlein Nazi stronghold, Teplitz, near the northern frontier, and one of the speakers asked me to go along. We drove through Terezin, a handsome gray-stone town where the young people were swimming in the moat. There were gypsy wagons of carved wood on the road, and the land is green and rolling and rich with grain.

So the Trouble Was Started

At Teplitz, normally, on a summer’s night, the whole population would be sitting in outdoor cafes under the moon, enjoying themselves. But now 3,000 German Social Democrats have crowded into a smoky hall, to roar approval of their speakers. When the orator tells them: “They have not made Nazi badges large enough so that you can see them from the air,” the crowd thunders its applause; it is a grim satisfaction to think that the same bombs will kill your neighbors, also Germans, also Czech citizens, but Nazis. They all know that the roads running parallel to that frontier, and leading into Germany, are barricaded with felled trees and barbed wire and cement, and guarded night and day, that soldiers stand in khaki silence under every railroad bridge and that all these bridges are mined. . . . And that no one may go up into the mountains.

The excuse for all this tension is the German minority. Of the three and a half million Germans in Czechoslovakia, about two million are Henlein Nazis. Up until 1935, eighty per cent of the Germans were Social Democrats who believed in democracy and got on all right in Czechoslovakia. Then 500 factories failed, the glass factories and the bead and porcelain and jute and sugar and textile factories, which employed these people and exported their wares all over the world.

The Henleinists blamed the Czechs for the world depression, and felt they were being willfully starved. A radio campaign started, and the German Nazi press took it up, and the towns and villages buzzed with talk: In Germany men eat and work and are happy . . . in Germany there are no Czechs to take jobs and humiliate us . . . Germany is a great nation and the Germans are a great race; Czechoslovakia is a little country and the Czechs are a small Slavic race. Why should we be ruled by Czechs? . . .

So the trouble was started. After Austria became Germany it flared up, and now everyone can see it.

Mikulov is a market and manufacturing town and a church with a tower like a red beet dominates it. Two thirds of the population is German. There used to be 450 soldiers in the town, and now there are 4,000, and the fields sprout pillboxes, and the trees that fringe the railroad track along the frontier hide machine-gun nests. In a cafe on a side street a German Social Democrat journalist, a Jewish lawyer and a Jewish merchant’s wife are having afternoon coffee. The lady’s family has lived in Mikulov for three generations and runs a wine shop. They are selling the wine shop for nothing and moving inland to Brunn. Since the first of May, she says, no one buys from them and no one speaks to them on the street. They seem to have lost their friends, but they were always happy here before. “We are not afraid of war,” she says. “We are afraid of the mob.”

One Hundred Per Cent Unemployed

The Jewish lawyer is a captain in the reserve of the Czech army; he has no more clients. But he is staying on, to see what happens. If war comes, he joins the army at once. He says he has seen a great many things he doesn’t like and he wouldn’t mind fighting. The journalist tells of a friend of his, Johann Schneider, an old man, a Social Democrat for twenty years. Johann was too old to work in the fields, so the journalist got him a job as orderly in the Mikulov hospital. Johann needed the work badly. The head doctor at the hospital is a Henlein Nazi and he gave Johann the choice of joining the Henleinists or being fired, and Johann joined the Henleinists, having first miserably explained it all to the journalist.

Gottesgab sits on the top of the Giant Mountains, two kilometers from Germany, and is cold even in summer, and in winter the snow comes up to the little windows on the second floor of the houses. It is a ski place, and used to live on the tourist trade, but now there is no tourist trade, and Gottesgab is one hundred per cent Henlein Nazi and one hundred per cent unemployed. The big man in a green tweed suit with a little green-feathered hat once taught people how to ski, and now he runs the local Henlein party. He is a nice man, and gets his politics out of the newspapers. He says that they do not want war, they want work. It is the fault of the Czechs, who maintain such bad relations with Germany, that no tourists want to come to Gottesgab any more.

He leads me about the village from miserable hut to miserable hut, where children are eating bread in hot water for lunch, and ten people sleep in one room, and the poorhouse for the old people is a building out of a bad dream. He shows off the misery of this place, a real and tragic misery, and says, with simple, impractical conviction: “If we had autonomy it wouldn’t be like this.”

I said: “Do the people here care about politics?” and he laughed.

“If we had work and food and clothes, do you think we would be wasting our time going to meetings?”

So they all came out to show me the road to take to the next village, and saluted with the Hitler salute and said: “But things will be better soon, you wait and see. . . .”

And I thought, in case of war, this would be a starving no-man’s land, lost in the low wet clouds.

The frontier is a tiny stream that you could jump across, and just over there in Germany, on a housetop, is a giant swastika, made of red electric lights, and it shines into Czechoslovakia.

“The whole country will be a battlefield,” the colonel said. “There will be no rear guard.”

We were sitting in his office; there were a polished wooden desk, two chairs, an iron camp bed, maps, and photographs of famous generals in modest frames. He was a blond and rosy man, with a mind that ranged carefully over all the problems of peace and war—a very civilized man indeed.

Any country, for that matter, can be a battlefield now, with the air loud with the noise of planes—the black planes like wasps, and the silver planes like dragonflies—and bombs as heavy as 2,000 pounds dropping like meteors on a helpless city. We had the maps out; from Dresden to Prague, a half-hour flight for a bomber. . . . In the last war, it averaged 12,000 shells from antiaircraft guns to bring down one plane. Now it requires a few dozen shells, so the colonel says.

The Czechs have great confidence in their antiaircraft guns and listening apparatus, and the human organization to warn of raids.

It is believed by German military authorities that the air force of Czechoslovakia is roughly 1,500 planes, a huge number to protect a country that size, but even so . . . “We are building camps now for children in the center of the country, where we hope they will be fairly safe from bombing,” the colonel said. “The C.P.O. is the civil organization against air attack; they are trained to give the alarm before raids, to manage refugees and evacuation work, to undertake fire prevention, and dig out bodies. There is also a civil unit trained to do quick construction work to block a rapid advance by a motorized army.” (I thought of the hayracks loaded with cement, and yesterday loaded with grain, and how they would block a road, holding up the motorcycle machine-gun units, the small tanks, the armored cars, while the defending army caught them in cross fire from the black forts. . . . Nice picture, I thought.)

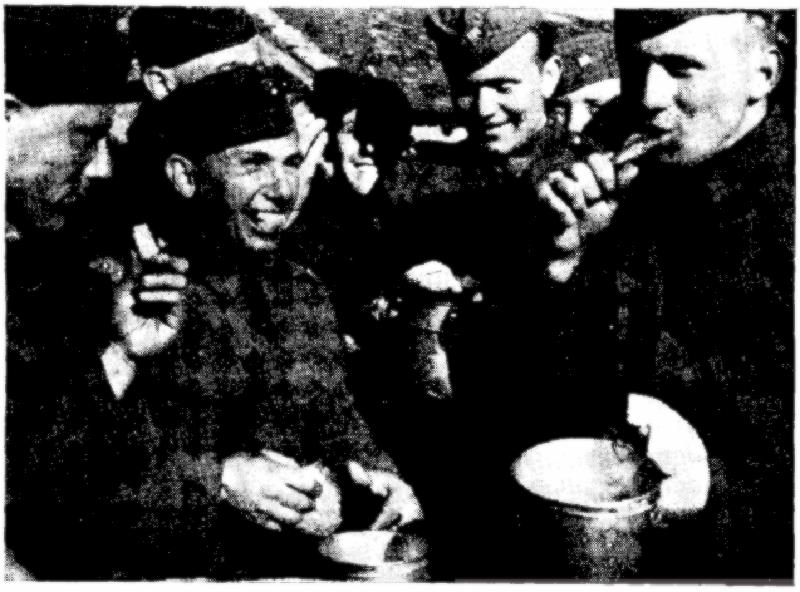

Backbone of Czechoslovakian defense and chief hope of maintaining its independence is its well-equipped standing army of 180,000 men. Infantrymen, here at mess, resemble American soldiers.

“We have organized food conservation, and laid in huge stocks; this would also be essential if the enemy uses gas on the fields. The civil transport system is planned, the replacement of men by women, in factories—there is a mobilization plan for the entire country. In time of war, the whole civil population must work; it is the best way to avoid panic, and it is necessary.”

He said: “The Germans are good soldiers, good organizers, good thinkers, but they always underestimate their adversary.” He did not say it braggingly. He went on, with his finger on the map, tracing the frontiers, to show Czechoslovakia’s allies. The finger stopped at Poland: “Three fourths of the Poles disapprove Beck’s policy; we think Poland will remain neutral.” His hand moved to Rumania: “Our ally.” East of Rumania, on the map, the vast pinkcolored sweep of Russia: “Russia is a great Slavic nation and perhaps the strongest military force in the world; she will help us. We are not afraid of Communism, because we are a good democracy, and social reforms come here without any need of revolution.” The finger moved back and hesitated over Hungary and he said nothing. He traced the long length of Italy and said, “Neutral . . .”

Gas Masks at the Movies

Bernmann is a curious character. He is so rich that he can live even in Germany, though he is a Jew. He speaks many languages well, and all of them with an accent. He is a learned and charming man, who would rather talk about books and writers than anything else; and suddenly here he was in Prague (at this season he is usually in London, and later on in his home in Capri). He said he had come back, when the trouble started, just before the mobilization. He intended to go into the army. He was an officer of the reserve and a Czech citizen, he said. He had sent his family to the country in England, and he was staying here to watch developments. He was very optimistic. Though Czechoslovakia needs zinc, copper, pig iron and nickel, she has been importing these for two years from England, and now has a supply adequate for six months’ manufacturing. The munitions factories were being moved south into Slovakia—there were eight great hidden factories there, out of danger.

The license for the Bofors antiaircraft gun, a gun with photographic lenses, sound detectors and automatic range correctors, had just been bought from Sweden. The Avia bombing plane is faster than the Junkers. Letov, Aero and Mraz are also putting out fast, fine planes and plenty of them. Moreover, he went on, though the army now is only 180,000, this country is capable of putting two and a half million men in the field rapidly. (The active army and trained reserve of the United States is 474,378, and Czechoslovakia is about as big as Illinois.) “If you stay awhile,” he said, “I’ll take you to the movies. You’ll see something interesting. In two weeks, all cinemas are required to have as many gas masks as seats. . . .”

Greatest Armament Works in Europe

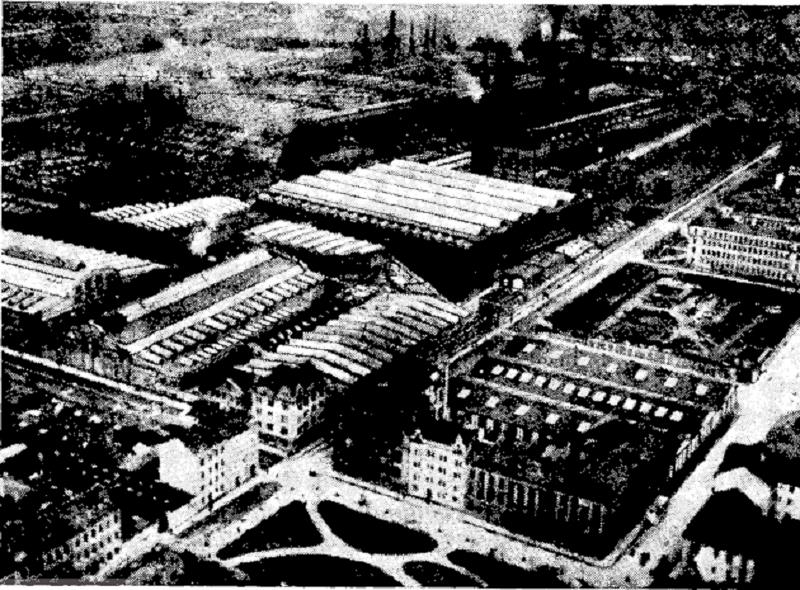

From the road you can see the chimneys of Pilsen pointing up above the plain. If you stop the car, down there to the left is the Skoda works, one of the greatest armament producers in Europe. The factories cover 400 acres of land and 30,000 people work in them. It is not a place you can loaf about, staring. One of the directors gave us lunch in the Skoda hotel. The dining room was shadowy, because all windows are covered with black paper against air raids.

Prime objective of enemy bombers would be the vast Skoda munitions works at Pilsen, the heart of Czechoslovakian wartime industry, and here, in the event of war, is how it would look from enemy planes.

There has been constant practice—the siren warning, the lights out, the empty streets and crowded refuges, then the all-clear and the city normal again—for two years. The director was optimistic too: he spoke of the quality of the Czech army with a patriot’s pride and of its equipment, with professional delight.

The Sokol has its headquarters in a pale yellow building, surrounded by tennis courts and playing fields, in the old part of Prague. Sokol is a sports organization, one of the oldest in Europe, and 786,000 people of all classes and professions belong to it, and, weekly, practice in unison, throughout the country, the gymnastic exercises that are the basis of their training. They believe in the old saying, “A sound mind in a sound body,” and they do not like politics. They will not admit either Fascists or Communists to their organization. But whether they like politics or not they are—like all Czechoslovaks—ardent patriots.

Thomas Bata was a cobbler. Now the Bata family runs Zlin, the most modern manufacturing city in the world, and it is their kingdom. You can like it or not, but it is very impressive. It stretches up and down gentle hills, in the center of the country, a square steel-concrete-and-glass city, in which Bata provides homes, swimming pools, tennis courts, schools, museums, libraries, movies, stores, restaurants and work for 32,000 people.

Bata makes shoes on the grand scale, and tires and stockings and various kinds of leather goods. Some years ago he started making sport planes—the Zlin 21, for the use of his salesmen in Africa, India and on the continent. It is said everywhere that this sport plane has been perfected into a fast pursuit plane and that the Zlin factories can turn them out in quantity, when necessary. Meanwhile 6,000 people in Zlin are trained in anti-air-raid service; women are trained to care for wounded; men are taught fire control and mass evacuation of the city; children are instructed to live in camps in the hills around Zlin if it becomes necessary to empty the city.

Bata publishes ten newspapers; the director of this amazing literary machine had explained the working of the factories to me and now he explained himself. I had asked him his politics. “I am a Democrat,” he said. “I hate nobody and nothing. To hate anyone is nonsense. I am a Democrat and I will always live independently. How others organize is their own business. But I will not accept any system that makes me a slave. So I will work for my state.” It developed that he knew the writings of Goethe by heart and had a German tutor for his children; that he thought the world was ruining itself because people spend their time in political argument when they should be working.

Bullying Will Not Work

“You can trace the growth of Henlein in this country by looking at the fall in export figures,” he said. “It is as easy as that.” I asked him what he planned to do in time of war and he said, “Everything here is planned for, the work for the whole city and for each one of us. I cannot talk to you about it, but I know. And I can tell you this: We do not want to fight anyone. We are busy and we could be a prosperous nation if we were let alone. But we were oppressed for three hundred years, and if anyone tries to take our republic away from us now, we will fight until there is not one of us left.”

At the foot of Castle Hill is the charming baroque palace of the Prime Minister. Dr. Milan Hodza is a man who holds himself very straight, speaks slowly and carefully, and does not need to waste time impressing his visitors. He has close-cut dark hair and mustache, steel-rimmed glasses, a narrow mouth and a wide, obstinate nose. He talks much more definitely than most statesmen do.

We sat at the table where the cabinet sits, under the picture of Masaryk. “For the moment,” Hodza said, in his neat English, “the collaboration of the three democracies has prevented war. But we must face Europe as it is. I do not believe that Germany is a country where hunger or economic inadequacies will produce revolution. They have the strongest discipline in the world, and the mystic faith—the religion—of Nazism. I believe therefore that for peace, it is between the powers” (by which he meant the balance of power) “and tolerance. This is the only way we can work out a reasonable solution.

“Bullying will not work on us; we have proved that. We will grant certain reasonable and just demands of the Henleinists, but we will go no farther than the integrity of the state allows.

“The people of this country are ready in every branch to defend themselves. But I do not believe war will come. The immediate issue is whether the reasonable elements in Germany will be able to control the extremists, by making them realize that a war against the three democracies is impossible.”

As I was leaving, he said: “The crisis is not over. By that I mean that none of us can take a vacation: we must stay and watch.”

But one wondered how long any armed peace can last, and just how long the people in a country can bear the strain of waiting and watching, and how long Europe can impoverish itself for guns. . . .

Czechoslovakia is a country where the land is divided up into narrow strips of varying green and the newly-tilled soil lies in mauve bands beside the green. The peasants work for themselves, and the little bourgeois with his shop or factory or office, and the civil servant, and the professional man, are all equally rich or equally poor, depending on your standards. You can count the people with five million dollars on your hands: there are the Bata family, with shoes; the Waldes, who make buttons; two members of the Petscek family, who have coal mines; Weinmann, who owns coal; Elbogen, with sugar refineries; Kubinsky, with textiles; and the Ringhoffer family, who manufacture airplane engines and the Tatra cars.

They are mostly self-made men and they are not much talked of. But their sentiments probably resemble those of any man in the street: they do not export their capital and they live at home; their fortunes and their lives are bound up with the future of Czechoslovakia. And their patriotism is locally judged by the large amounts they subscribe to the National Defense Fund. After the millionaires, incomes drop to half a million, and then to twenty-five thousand, which is a tidy fortune in this country. As there is little external show of wealth, so there is little external evidence of class difference. The son of former President Masaryk dines on Sunday at the great outdoor restaurant at Barrandov, and knows the cigarette waiter well, as they went to school together; the stenographers and clerks from Prague also dine there. The heir to the Waldes millions goes to a public commercial high school.

A Somber Procession

All these people are united in their will to go on as they are. They want to work and make their country bloom: they want to be quiet. But Czechoslovakia slants across central Europe, and beyond lie the oil fields of Rumania, the wheat of the Ukraine, and the Black Sea. If a great power controlled Czechoslovakia, it would have a strong strategical position for striking westward into Europe, toward the Mediterranean. Czechoslovakia’s tragedy is that it is in the way.

If the somber procession is to continue—China, Ethiopia, Spain—then Czechoslovakia is next. And she is ready, and waiting, not afraid, but surely not glad. No man likes to live with doom hanging over tomorrow. It is horrifying for an intelligent people to realize that twenty years of constant and constructive effort to build a country can be wiped out in a month. They wait; there is nothing else for them to do. And hope. And watch the former house painter who now holds the lightning in his hand.

Learn more about Konrad Henlein, here.

Learn more about the book, A Stricken Field (1940), a novel set in Czechoslovakia at the outbreak of war, here.

Learn more about Martha Gellhorn, here.

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Become a friend and get our lovely Czech postcard pack.