Do you ever wonder where the first cup of coffee was in Prague, or how it even got there? The first Europeans to get acquainted with coffee were mostly travelers. The first traveler from the Czech lands to mention coffee was Kryštof Harant of Polžice and Bezdružice (Czech: Kryštof Harant z Polžic a Bezdružic, 1564 – June 21, 1621). He was a Czech nobleman, traveler, humanist, soldier, writer and composer. He joined the Protestant Bohemian Revolt in the Lands of the Bohemian Crown against the House of Habsburg that led to the Thirty Years’ War. He discovered coffee on his journey to Constantinople in 1598.

Following the victory of Catholic forces in the Battle of White Mountain, Harant was executed in the mass Old Town Square execution by the Habsburgs. Learn more about him and other travelers in the post we wrote entitled Prague Streets Named After Czech World Travelers.

Coffee has been used on the old continent since 1650, mainly thanks to Arab and Armenian ambassadors. It first spread as a sign of luxury, mostly in the noble yards. Her delicious taste began to spread rapidly to the intellectual and artistic circles.

The first European coffee house apart from those in the Ottoman Empire and in Malta was opened in Venice in 1645. The first coffeehouse in England was opened in St. Michael’s Alley in Cornhill, London. The proprietor was Pasqua Rosée, the servant of Daniel Edwards, a trader in Turkish goods. Edwards imported the coffee and assisted Rosée in setting up the establishment. Oxford’s Queen’s Lane Coffee House, established in 1654, is still in existence today.

In Germany, coffeehouses were first established in North Sea ports, including Bremen in 1673 and Hamburg in 1677. The first coffeehouse in Austria opened in Vienna in 1683 after the Battle of Vienna, by using supplies from the spoils obtained after defeating the Turks. The officer who received the coffee beans, Jerzy Franciszek Kulczycki, a Polish military officer of Ukrainian origin, opened the coffee house and helped popularize the custom of adding sugar and milk to the coffee.

Melange is the typical Viennese coffee, which comes mixed with hot foamed milk and a glass of water.

History of Drinking Coffee in the Czech Republic

Czech references are scattered and date to sometime in the early 18th Century. Coffee was initially only sold in pharmacies because it was considered a gastric remedy for its bitter taste. It was also quite expensive, so it was consumed only in the houses of the richest people at first. Then servants were acquainted with the coffee and soon it was being enjoyed among the ordinary people.

In Brno, the first café was founded in 1702 by Ahmed, a Turk who gave the city council a cavalry concession, because the Archbishop of Visegrád himself was called in for it, as well as the ceremony of the capital of the monarchy just before the Turks Count Kollonitsch.

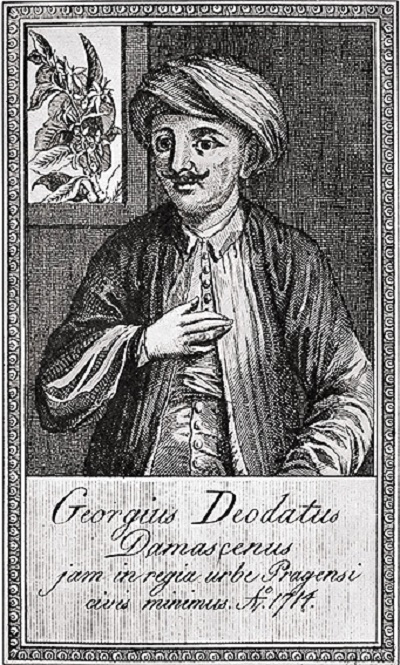

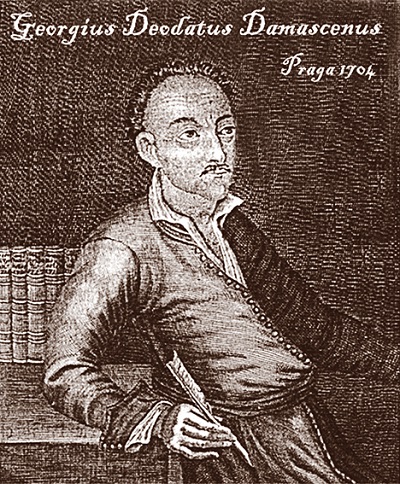

The first Prague café is thought to date from 1711 and was established by a writer (Jiří Deodat) on the Mala Strana side of the city.

(Above scan from Máj, 1906, issue number 8.)

In 1714, an Arab named Jiří Deodat (Georgius Deodatus Damascenus) opened the first two Prague cafes at the Golden Snake and the Three Ostriches. (kavárny U zlatého hada a U Tří pštrosů.)

Another source states that the first café was created by Jiri Deodat also known as Georgius Deodatus Damascenus.

In 1704, Jiří Deodat traveled to Vienna, where he tried to do business unsuccessfully. From there, he moved to Prague, where so far, coffee had only been sold in pharmacies. Seeing an opportunity, he established the first coffee shop.

Initially, he offered boiled coffee on the streets of Prague, where folks immediately noted his sovereign mire and Turkish suits.

Imagine him, quite literally a walking billboard, with coffee on his headpiece and sugar in his pockets. He walked along Prague streets in exotic clothes and his turban, offering a passage of an unknown drink to passers-by.

At first, people did not like the coffee, but it was more of a curiosity to taste the unknown, an exotic beverage. In Bohemia, coffee was only the privilege of a rich burgher population. Deodatus extended his service with the delivery of coffee to these burgher houses.

This was most uncommon at the time and his liberty allowed him to build fast wealth which thus allowed him to buy the bourgeois right (at that time) to open a cafe, and he did so – at the house v domě u Kornovů v Liliové ulici (today U zlatého hada).

Finding his ideal location, he married in Prague and fathered three children.

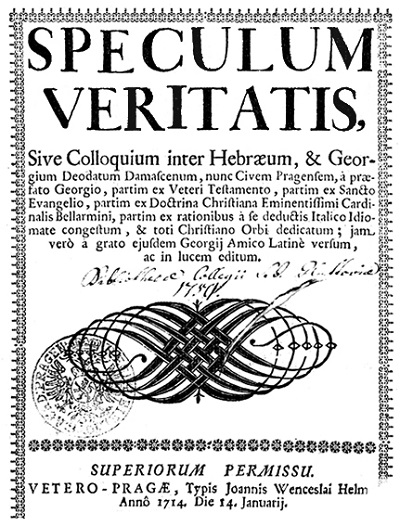

He also authored several writings, mostly with religious and moral themes.

Most historians will agree that it was Jiri Deodat who founded the first café in 1711 for the new delicacy known as coffee.

But like with most historical stories, there is another account as well…

In 1714, Jiří Deodat, a Turkish coffee maker from Damascus in Syria, opened the first Prague coffee house (later known as “kafírna”.) At first, he used to walk through the streets in Arabic clothing, with cups, sugar, water, coffee, and a wood coal-fired oven. Coffee was drunk whilst standing.

(Above scan from Vlastencové z Boudy: historický obraz by Josef Jiří Stankovský, 1904.)

Later on, he rented a wooden hut at the end of the Charles Bridge. After some time – surely based on his business success – he moved into a shop beside the Lesser Side tower, in the residential quarters of the former customs house. He sold coffee here until his death on December 2, 1730.

According to legend, he was in the Three Ostrich House at Malá Strana. But he stayed in the house in Liliova Street. He had such success with the café that he even bought it and lived here with his wife, who was a Czech and together they had a few children. It is said that he learned to speak Czech in good time, even though some words were slightly confusing. In fact, he trusted his linguistic abilities so much that he published several theoretical writings on the Catholic religion. But one of his writings became fatal. He sharply defined himself against the Prague Jews, and thus made them his enemy. And since the Jews of Prague were always proficient merchants, apparently they all got together and made sure that Deodatus’ trade would soon stagnate. Quickly he lost his big estate and eventually, his wife and children left.

Unfortunately, his life’s fate does not have a happy ending. It is believed that he died destitute and alone.

It was said that from the “house near the bridge,” he was carried out (according to the record in the death register) in his coffin.

Deodat, who eventually converted to the Catholic faith, was buried was buried in the cloister of St. Thomas.

By 1808, there were 26 cafés listed following a city survey.

To this day my mother and her friends drink Turek, or Turkish coffee.

Below is a short video on how this delicious beverage is made properly.

Coffee Drinking Culture

Obviously, today coffee can be enjoyed in one of the many beautiful and historic cafés in and around Prague. Some of the cafés have a long history and we invite you to learn more about them at this link:

The Bourgeois Art Nouveau Cafés of Prague

It took a while for coffee to expand and become popular, mainly for the initial high price. In the 20th century between the wars, at a time when the cafés were also on the rise, drinking coffee became a symbol of a new lifestyle. Unfortunately, this boom was interrupted by the Second World War, which brought about a coffee “fast” of sorts, and at the time only coffee substitutes like chicory or melta (malta) were sold instead of coffee.

After the war, private roasters were nationalized, and many of the bourgeois First Republic cafés were mostly closed. Quality coffee had a big deficiency in the market and coffee again became unavailable for many families. Perhaps these circumstances are what paved the way for our Czech “turek” coffee, which very quickly became the cheapest way to prepare coffee. There used to be an unwritten rule that “Turkish” coffee should never have milk but that is no longer the rule, though die-hard turek drinkers will say that to keep it pure, no milk or sugar.

And after mentioning the Czech habit of drinking “Turek”, we should also mention the meritorious activity of Mr. Zdeněk Žáček, who was an important expert in the field of commodity knowledge, especially in coffee.

In 1962, Žáček was granted a patent for the technological preparation of decaffeinated coffee.

That’s right… A Czech came up with decaffeinated coffee, too. (Good way to accompany the sugar cube, also a Czech invention!)

The patent for the preparation of decaffeinated coffee belongs to the Czechs! Although we must add that the first successful extraction of caffeinated grain actually came from the German chemist Ruge in 1820, it was Zdeněk Žáček who filed and subsequently won a patent for its preparation.

Finally, when Czechs drink coffee, they do want it brewed, with or without caffeine. The consumption of instant coffee is significantly lower in the Czech Republic than in most of its neighboring countries.

If you enjoyed this post, you’ll surely like the following:

- Karel Kulík’s Cheerful Calendar or How Coffee Came to Prague

- The Bourgeois Art Nouveau Cafés of Prague

- Prague Streets Named After Czech World Travelers

We tirelessly gather and curate valuable information that could take you hours, days, or even months to find elsewhere. Our mission is to simplify your access to the best of our heritage. If you appreciate our efforts, please consider donating to support this site’s operational costs.

See My Exclusive Content and Follow Me on Patreon

You can also send cash, checks, money orders, or support by buying Kytka’s books.

Your contribution sustains us and allows us to continue sharing our rich cultural heritage.

Remember, your donations are our lifeline.

If you haven’t already, subscribe to TresBohemes.com below to receive our newsletter directly in your inbox and never miss out.