Czech language developed at the close of the 1st millennium from common West Slavic. Until the early 20th century, it was known as Bohemian but I will refer to it as old Czech language in this post. I wanted you to hear a wonderful example of old Czech language, at least as old an example as we can actually listen to, so I found some recorded examples for you to enjoy…

The earliest written records of Czech date to the 12th to 13th century, in the form of personal names, glosses and short notes. The oldest known complete Czech sentence is a note on the foundation charter of the Litoměřice chapter at the beginning of the 13th century. In the 14th century, Czech began to penetrate various literal styles. Official documents in Czech existed at the end of the 14th century.

The period of the 15th century from the beginning of Jan Hus’s preaching activity to the beginning of Czech humanism. The number of literary language users enlarges. Czech fully penetrates the administration. Around 1406, a reform of the orthography was suggested in De orthographia bohemica, a work attributed to Jan Hus – the so-called diacritic orthography.

The period of the mature literary old Czech language date from the 16th to the beginning of the 17th century. After the invention of book-printing, the so-called Brethren orthography stabilized in printed documents. The Bible of Kralice (1579 – 1593), the first complete Czech translation of the Bible from the original languages by the Unity of the Brethren, became the pattern of the literal Czech language.

The period from the second half of the 17th century to the second third of the 18th century was marked by confiscations and emigration of the Czech intelligentsia after the Battle of White Mountain. The function of the literary language was limited; it left the scientific field first, the discerning literature later, and the administration finally. Prestigious literary styles were cultivated by Czech expatriates abroad. The zenith and, simultaneously, the end of the florescence of prestigious literary styles are represented by the works of Jan Amos Komenský.

The changes in the phonology and the morphology of the literary language ended in the previous period. Only the spoken language continued its development in the country. As a consequence of strong isolation, the differences between dialects were deepened. Especially, the Moravian and Silesian dialects developed divergently from Common Czech.

The abolition of serfdom in 1781 (by Joseph II) caused migration of country inhabitants to towns. It enabled the implementation of the ideas of the Czech national awakeners for the renewal of the Czech language. However, the people’s language and literary genres of the previous period were strange to the enlightened intelligentsia. The literary language of the end of the 16th century and of Komenský’s work became the starting point for the new codification of literary Czech.

Of the various attempts at codification, Josef Dobrovský’s grammar was ultimately generally accepted. Purists’ attempts to cleanse the language of Germanisms (both real and fictitious) had been occurring by that time. The publication of Josef Jungmann’s five-part Czech-German Dictionary (1830–1835) contributed to the renewal of Czech vocabulary. Thanks to the enthusiasm of Czech scientists, Czech scientific terminology was created.

A turning point occurred at the end of the 18th century and the beginning of the 19th century, due to a movement called the National Revival, based on two currents of thought: the Enlightenment and the impending Romanticism.

The Enlightenment emperor Joseph II abolished serfdom in 1781 and thus enabled people from the country to move to the cities to strengthen the Czech element in themselves as well as to study. Josef Dobrovský, the rationally-oriented historian and founder of Slavic Studies, author of the Ausführliches Lehrgebäude der böhmischen Sprache (1809) (in German), considered the inconsistent colloquial use of Czech of that time destabilized, and decided to draw on the tradition of the highly developed humanistic Czech of the 16th century as the basis for grammatical description.

He selected esp. the classic language of the Kralice Bible, which was considered prestigious on the entire territory, including the Slovak part. Subsequently, Dobrovský´s description was taken as the basis for the standard language (spisovná čeština ‘Literary Czech’) that was thus drawn apart from the Czech commonly spoken in Bohemia, known as Common Czech.

The Enlightenment rationalism did not yet allow this generation to believe that Czech would again become a fully functioning standard language. That only came when the following generation, influenced by Romanticism, above all by J. G. Herder, began an enthusiastic renewal of the standard functions of Czech.

The leading spirit of this generation was Josef Jungmann. Czech in science and literature required a significant enrichment of the lexicon with specialized terminology and poetic means. Jungmann and his colleagues compiled in a rather short time the five-volume Slovník česko-německý ‘Czech-German Dictionary’ (published 1835-1839). They summarized the older lexicon and enriched it with many new words, which they either created (in the spirit of the Dobrovský’s Grammar) or adopted from other languages, above all Slavic ones.

Here’s a Pilsner Urquell commercial from 2010 that I found on YouTube. It shows Josef Jungmann get inspiration for the revival. But then when they deliver his beer, he slips up and says “danke”, which means thanks, in German!

Ah, Czechs and their humor!

Words such as soustava ‘system’, časopis ‘magazine’, odstín ‘shade’, rostlina ‘plant’, savec ‘mammal’, kyselina ‘acid’, přízvuk ‘accent’, čtverec ‘square’ and others come from Jungmann’s time. Today, it is a lesser-known fact that the words modřín ‘larch’, ropucha ‘toad’, podmět ‘subject’ and others were borrowed from Polish, and that krysa ‘rat’, tuleň ‘seal’, vzduch ‘air’, příroda ‘nature’ and others were borrowed from Russian.

More from Jungmann in regards to language, here.

If the above interests you, we recommend visiting the Wikipedia page on the History of the Czech language for more information about Czech language and its history.

The creation of the independent Czechoslovak Republic in 1918 was linguistically significant in that Czech became the official language on the territory of Bohemia, Moravia and the Czech part of Silesia. On the territory of Slovakia, the official language was standard Slovak; more precisely, formally the official language on the entire territory of the republic was “the Czechoslovak language”, which existed in “the Czech version and the Slovak version”.

First Sound Film in Czechoslovakia

The very first Czechoslovak sound film was Tonka Šibenice (Tonka of the Gallows) by director Karel Anton. It was screened in the the former Czechoslovakia on April 26, 1929 in the Ústí Alhambra cinema in Střekov. Another screening was held in August of that year at the Lucerna. Tonka Šibenice was the first Czech film with post-synchronized sound, although it plays primarily as a silent movie with intertitles.

The extraordinary Ita Rina is the title character in this melodramatic story. An innocent rural girl turned prostitute whose act of pity—keeping chaste company with a condemned man through the night before he is to be hung—returns to threaten her unexpected chance of happiness, as the bride of a young farmer from her native village. The stellar international cast, the sophisticated work of Egon Erwin Kisch and the innovative combination of silent and sonic means of expression from the film are still of European significance. It is remembered not only for the sound, but for the intense emotional power and bravura film making of Tonka’s final sequence, in which the dying heroine imagines the life that might have been hers.

You can read an excellent article on the film here.

You can watch the film here part 1 and part 2.

First Talking Film in Czechoslovakia

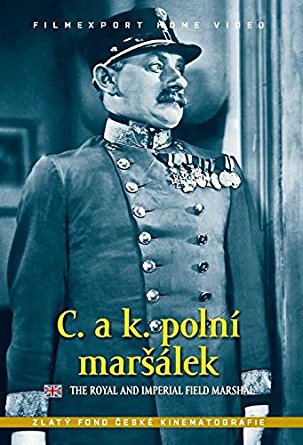

The first clip is from a film entitled C. a k. polní maršálek (Imperial and Royal Field Marshal) is a 1930 Czechoslovak comedy film directed by Karel Lamač and starring one of the most popular Czech comedians, Vlasta Burian in the lead role.

The first clip is from a film entitled C. a k. polní maršálek (Imperial and Royal Field Marshal) is a 1930 Czechoslovak comedy film directed by Karel Lamač and starring one of the most popular Czech comedians, Vlasta Burian in the lead role.

Also starring Theodor Pistek, Helena Monczáková, Mána Zenísková, Jirí Hron, Jan W. Speerger, Cenek Slégl, Jindrich Plachta, Josef Horánek, and Olga Augustová.

The film is about a doppelgänger of the highest ranking officer in the old Austrian army.

It is considered to be the first ever Czech language talking film released on October 24, 1930.

You can purchase the DVD here.

Fidlovačka

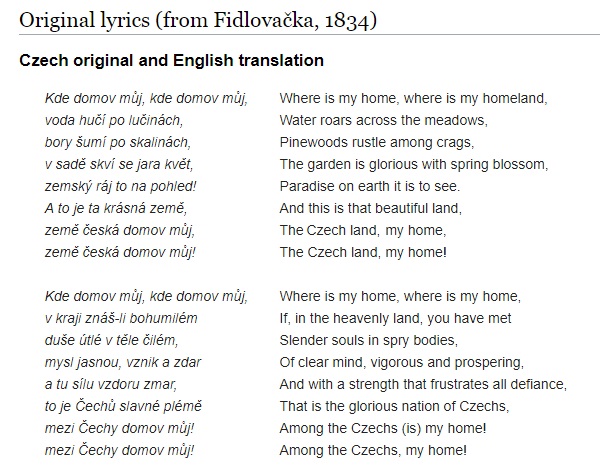

This next clip below is from a movie entitled Fidlovačka, another one of the first Czech talking motion pictures and is based on Fidlovačka aneb Žádný hněv a žádná rvačka (Fidlovačka, or No Anger and No Brawl), Folk Scenes of Prague Life with Song and Dance; a play written by the composer František Škroup and the playwright Josef Kajetán Tyl.

As a play, it was first shown on December 21, 1834 at the Estates Theater. (At that time it was called Královské zemské německé divadlo.)

Fidlovačka is considered to be a highly patriotic film for the Czech people because the national anthem was captured and recorded. Kde domov můj (Where My Home) holds a very important scene in the film (and the play). This film acted as a vehicle for a patriotic nation where national slogans were being sounded. Remember, that in this era, there was a great passion for reviving and maintaining the old Czech language.

Fidlovačka is an undemanding film, at the time especially pleasing for the country audience, which was primarily intended when it was being made. Like Božena Němcová’s Babička (The Grandmother), it was perfect to assist with the Czech National Revival movement.

Most Czechs will tell you that Fidlovačka is first ever Czech language talking film, but it was released a few months later, on December 18, 1930.

Fidlovačka was directed by Svatopluk Innemann and starred Antonie Nedosinská, Slávka Tauberová, Růžena Šlemrová, Jindřich Plachta, Jan Marek, Josef Rovenský, Jiří Sedláček, Eman Fiala, Marie Grossová, Čeněk Šlégl, Otto Zahrádka, Slávka Doležalová – Kulhavá, Otakar Mařák, Růžena Pokorná, Betty Kysilková, Emilie Nyschová, Ella Nollová, FX Mlejnek, Václav Pecián, Václav Menger, Emil Dlesk, Robert Ford, Ladislav Desensky, Bonda Szynglarski, Přemysl Pražský, Eduard Šlégl, and Zdena Kavková.

You can purchase the DVD here.

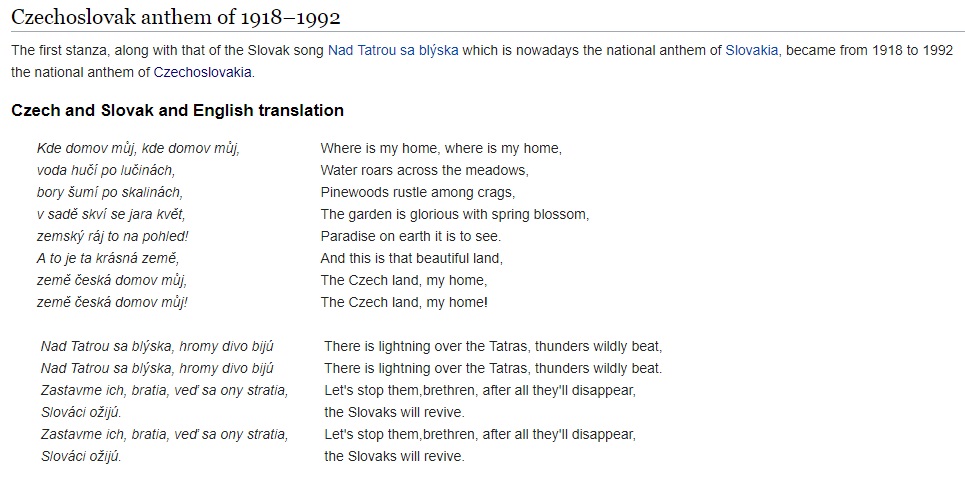

Many of you recognized Kde domov můj, the Czech national anthem since 1918 in the song.

The version in this film, especially will surely give you goosebumps and put tears in your eyes…

Kde domov můj

Everyone agrees that the music was composed by František Škroup, but what is very interesting, is that the hymn’s own melody is probably from Mozart. Yes, Mozart.

We find it in the second movement of his Concertant Symphony in E flat major for oboe, clarinet, bassoon and horn 299 b. Only musicologists know that Škroup must have “lifted” the short piece for he play, never realizing that someday it would become the Czech National Anthem. (Czech readers, more here.)

The Czech anthem is beautiful because it is different. It is like the Czech language.

Čeština je založená na slovese, to znamená, že je ohromně ohebná a akční. Má otevřené slabiky, žádné shluky souhlásek, je zpěvná. Písničku jsme nakonec povýšili na hymnu. A co se tam zpívá? Že je u nás hezky, nic víc a nic míň… – Zdeněk Mahler

We sing in her how our Czech landscape is beautiful. The music flows like our rivers, majestically and calmly. It is short and simple, without empty or pathetic words, and yet each note awakens pride and love for our home.

Quite honestly, I do not know a more beautiful anthem. So here is another clip in case you want to share it with family and friends. The shorter video below just shows the beautiful anthem.

The role of Mareš was sung by Otakar Mařák. Mařák was a tenor Czech opera singer, and a nephew of Julius Mařák who perfected his vocal skills at Prague’s School of Applied Arts as well as at the Czech Academy of Arts. Together with Emmy Destinn and Karel Burian, Mařák completed the trio of well-known early 20th century Czech singers.

With the split of Czechoslovakia in 1993, the Czechoslovak anthem was divided as well. While Slovakia extended its anthem by adding a second verse, the Czech Republic’s national anthem was adopted unextended, in its single-verse version.

More about the Czech National Anthem, here.

In 1936, another film forever captured old Czech language, this time with a Moravian dialect, Maryša directed by Josef Rovenský and starring Jiřina Štěpničková, František Kovářík, Hermína Vojtová, Jaroslav Vojta, Vladimír Borský, Ella Nollová, Marie Glázrová, Marie Bečvářová, František Hlavatý, Antonín Soukup, Josef Příhoda, Jan W. Speerger, Václav Menger, Karel Němec, Milka Balek-Brodská, Marta Májová, Josef Rovenský, and Karel Schleichert.

In 1936, another film forever captured old Czech language, this time with a Moravian dialect, Maryša directed by Josef Rovenský and starring Jiřina Štěpničková, František Kovářík, Hermína Vojtová, Jaroslav Vojta, Vladimír Borský, Ella Nollová, Marie Glázrová, Marie Bečvářová, František Hlavatý, Antonín Soukup, Josef Příhoda, Jan W. Speerger, Václav Menger, Karel Němec, Milka Balek-Brodská, Marta Májová, Josef Rovenský, and Karel Schleichert.

Maryša is a country drama about the tragic culmination of a forced marriage. Scenes were moved primarily for the greater spectacular effects of the Vlčnovský kroje or traditional folk costumes from the Vlčnov region. Their distinctive colorfulness brought the producers the idea of making several crowded costume scenes (wedding) for color material. However, the processed parts of the color copy abroad were not used in the normal distribution of the film.

Vlčnov is a picturesque South Moravian village lying 5 km from Uherský Brod and is arranged in a typical village style. The first record dates back to 1264 even though the history of this village began much earlier and is documented by archaeological excavations carried out in the area.

Maryša, especially in the sense of director Rovensky, also belongs among the most important works of Czech cinematography of the first half of the 1930s. We are grateful for all of the amazing kroje the film captured.

The Czechs

The Czechs (Czech: Češi, pronounced ; singular masculine: Čech , singular feminine: Češka or the Czech people: Český národ), are a West Slavic ethnic group and a nation native to the Czech Republic in Central Europe, who share a common ancestry, culture, history and Czech language. While the former regional dialects of Bohemia have merged into one interdialect, Common Czech (with some small exceptions in borderlands), the territory of Moravia is still linguistically diversified. This may be due to Prague in Bohemia for most of the history, as well as the fact that Brno and Olomouc used to be predominantly inhabited by a German-speaking population.

Read more about the Czech language here.

The Moravians

Moravian dialects (Czech: moravská nářečí, moravština) are the varieties of Czech spoken in Moravia, a historical region in the southeast of the Czech Republic. There are more forms of the Czech language used in Moravia than in the rest of the Czech Republic. The main four groups of dialects are the Bohemian-Moravian group, the Central Moravian group, the Eastern Moravian group and the Lach (Silesian) group (which is also spoken in Czech Silesia). While the forms are generally viewed as regional variants of Czech, some Moravians (522,474 in the 2011 Census) claim them to be one separate Moravian language. Southeastern Moravian dialects form a dialect continuum with the closely related Slovak language, and are thus sometimes viewed as dialects of Slovak rather than Czech.

Some typical phonological differences between the Moravian dialects are shown below on the sentence ‘Put the flour from the mill in the cart’:

Central Moravian: Dé móku ze mléna na vozék.

Eastern Moravian: Daj múku ze młýna na vozík.

Lach: Daj muku ze młyna na vozik.

Common Standard Czech: Dej mouku ze mlýna na vozík.

Read more about Moravian Czech here.

The Slovaks

The Slovak language is a West Slavic language. Historically, it forms a dialect continuum with the Czech language. Its standard orthography is based on the work of Ľudovít Štúr published in the 1840s. It continued to be strongly influenced by Czech, especially in the early 20th century when a single Czechoslovak language was the written standard, but it was introduced as a separate standard in the Czechoslovak Socialist Republic in the 1960s. The six-volume Dictionary of the Slovak Language (SSJ) was published during 1959–1968, and the Constitutional Law of Federation in 1968 confirmed equal rights for the Slovak and the Czech languages in Czechoslovakia. Since 1993, Slovak has been the official language of the Slovak Republic.

Read more about Slovak language here.

Sources: Wikipedia, Czech National Revival.

If you have not yet subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, use the form below now so you never miss another post.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Become a friend and get our lovely Czech postcard pack.