In looking at Czechs in New York and their history in the United States, we cannot overlook Bohemia. Today, Bohemia is a hamlet in Suffolk County, New York, United States. In 2010, the population was 10,180 based on the census. Bohemia is situated along the South Shore of Long Island, in the Town of Islip, approximately 30 miles from New York City.

Bohemia is bordered by Central Islip and Great River to the west; Islandia, Ronkonkoma and Lake Ronkonkoma to the north; Holbrook to the east; and Oakdale, Sayville, West Sayville, and Bayport to the south.

Long Island, N.Y. 1852.

But let’s travel back in time to when Bohemia was born…

Imagine that it is 1896 and we are back in the old country. We are trying to imagine what life is like in the new world. What has become of our Czechs in New York? Finally, we find an article which tells us of our brothers in America…

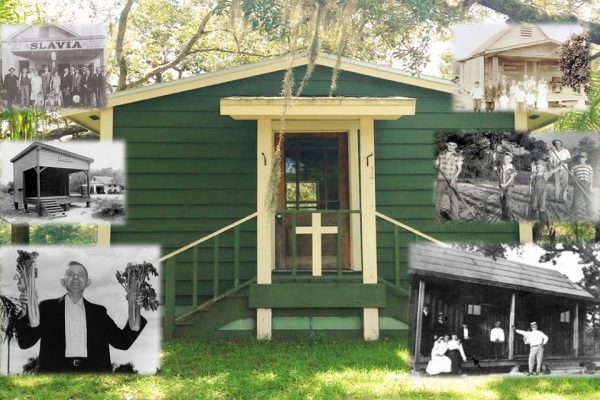

About 30 miles from New York City on Long Island, exists a small settlement which consists of 66 houses, a school, two churches, a cigar factory, a fire station, and a public building for meetings and theatrical performances, the last of which was given by the Czech economic association.

The settlement, the the exception of two families, was inhabited solely by Czechs and its founders were compatriots: Jan Vávra, born in 1819 in Zvánovice near Kouřim and native of Ondřejovští (in the district Kostelec nad Černými lesy), Jan Koula and Jan Kratochvil. All three, arrived to America at the end of 1854. An honorable memorial was constructed in their old homeland for their participation in the Prague Uprising of 1848.

At first they were doing poorly and things were not looking good for them in America. Limited opportunities existed for new immigrants in New York City. Their lowly economic state, after probably spending all they had on their ship’s passage, determined that they lived in the poorest and most densely populated sections of the city. Where they lived and where they worked were preordained by their immigrant status. They had to resort to working as street musicians for their livelihood. At the beginning of March 1855, Vávra became ill, and sought medical advice from a doctor. The doctor advised that he needed a place in the country where the air would do him good.

He soon found and purchased 5 acres from Alex. H. Wallis’ Lakeland farms. Everything looked wonderful on the map. But in fact, instead of gardens, buildings and factories they found a widespread forests. And to make matters worse, it looked like the forest had recently had a large fire so most of it was badly damaged. (Until the mid-19th century, the area that became Bohemia was a dense woodland a few miles south of the Lakeland Long Island Rail Road station.) Other than that, they could look out at the loneliness of the sea. Yet they had no choice, they had to move there. The deal was done. So it was to be Jan Vávra and his two friends, who helped with materials to build

Jan Vávra in Bohemia, Long Island, N.Y.

Vávra and Koula gathered wooden planks and began building. Thankfully, Koula was an excellent joiner (an artisan who builds things by joining pieces of wood, particularly lighter and more ornamental work than that done by a carpenter, including furniture and the “fittings” of a house, ship, etc.). While Koula worked on the construction of the building, the other two engaged in digging and cutting what was left of the forest.

The greatest stress and challenge to Koula, was the construction of a proper chimney. There were no bricks and when he built it of wood, it would catch fire. The work seemed endless for the three.

Kratochvil’s plot was about a mile from the others and when they wanted to visit each other in the evenings, they would have to climb a tree to gain direction and see where they were going.

After a while, their money ran out and once again they had to look for work. They walked along the shore, which had been long since low tide around lunchtime, and after 1 1/2 hours they stood at the farmhouse of Colonel William Ludlow located on the shores of the Great South Bay and the Atlantic Ocean. They agreed to work for him for the sum of 50 cents a day which they were to take from the farm in provisions, food, etc. This is how they survived and what they did for the next three years.

They continued to visit each other, walking at night with a smoldering torch to light their way along the primitive landscape. When matches were forgotten or ran out, they would use their planing tools to quickly glide over rags, with their wives blowing at the sight of any spark.Once, the rapid movement stuck Mrs. Koula and as she was pushed back, she fell on the stove which immediately fell over. Injured but able to get up, she realized that the fire had lit.

Needless to say, life was not easy for them.

Ludlow finally offered Kratochvíl and his wife a place at his farm and they resided there for two years. After two years, they had saved enough to resume building their home on their plot. In the meantime, Koula had moved to Boston with his brother, and so now only the two Czech families remained.

Every day was a struggle. They had to walk 3 miles to Holbrook just to get milk. Once, as she was walking this long path alone, Mrs. Vávrová got turned around and lost. Clearly terrified, she later appeared at Central Islip. She was beside the track, frantically crying, and pointing west to the confused onlookers. Just at the time, the train was there and the conductor offered to take the lady to Brooklyn. From there, she was finally able to make her way home.

Things like this happened all of the time to newcomers, especially when they did not speak a word of English. Lost and confused, taken advantage of in property dealings, and often desperate and hungry, the first Czechs had a very difficult time and required a great deal of fortitude to “make it” in America.

By the spring of 1859, eleven other families settled in the area: Josef Dvořák. Matěj Nohavec, Jan Nohavec. Josef Jedlička, Matěj Wilda, Jan Rosa, Matěj Fišer, Josef Kohout, Tomáš Bucháček, Václav Ryba, and Vojta Spálený. However, the last two (Ryba and Spálený) did not last a year and moved away almost as quickly as they came.

Since the settlement had grown, it was time to think about a name. It was known as “Tábor” after the Hussite encampment, and by 1862, more Czechs had come to settle: Jakub Karšík, Antonín Benedikt, Jan Honzka, Blazej Kovanda, Vaclav Šejtek, Jan Jendele and František Laně, all of them coming from Horažďovice, a town in the Plzeň Region. The group had originally planned to go on to Boston, Massachusetts, but at the advice of Koula, they decided to give Tábor a fair try.

By now the settlement began to flourish, but there were still fair difficulties. The community of Lakeland began to intervene because they felt the children of Tábor should be schooled there.Upon hearing this, the community of Sayville also wanted the Czech children in their school, and both sides seemed most interested because there was a school tax which was being enforced.

Obviously the lack of a school was becoming a problem.

In addition, there was no church or cemetery. Czechs kept coming. Jan Pouska, the parents of Jan Koula, and then Josef Koula and his wife, moved to Tabor. In 1865, the older Mrs. Koula died but there was no cemetery where she could be buried. So Jan Rosa took to her Sayville and pleaded with the preacher, Reverend Clark, to allow her to be buried at the Congregational Cemetery. At this first funeral of a Czech in the area, the prayers were in the Czech language. And Josef Koula had an organ sent from Boston so he could play in accompaniment to her service.

Since then, Reverend Clark began to show great interest in the village. He would show up every Sunday to oversee a service and would later greatly enjoy the Czech national songs sung afterwards at Jan Nohavka’s house. Discussions of a school were also headed by Reverend Clark, who began to speak of the necessity to his perishers in Sayville and took up a collection.

Each week he would make an effort to share the importance of a school for the children of Tábor and raise more money. Clark’s collections in Sayville began to add up. In 1866, a detached school district was approved, but now land was needed, and of course more money to get the school built Reverend Clark turned to Alexander Wallis, a New Jersey resident who owned large tracts of property in the area surrounding Tábor during the mid-eighteen hundreds. Wallis donated two acres for a school, and two more for a proper cemetery.

Each resident was given a burial plot of 16 by 20 feet, and locations were decided by a public drawing of numbers. Initially residents had to measure their own plots, but this became too complicated. (Later, in 1892 a surveyor was hired to properly lay out the cemetery.) The first person interred there was Mrs. Joseph Koula, who died in 1855 and was originally buried in Sayville. Her remains were moved when the Bohemia Union Cemetery opened.

Now that they had the land, once again the issue of money for the construction arose. Materials were expensive and so much would be needed. A plea was made to the Těl. Jed. Sokol who had been invited to make an excursion to Tábor from New York.

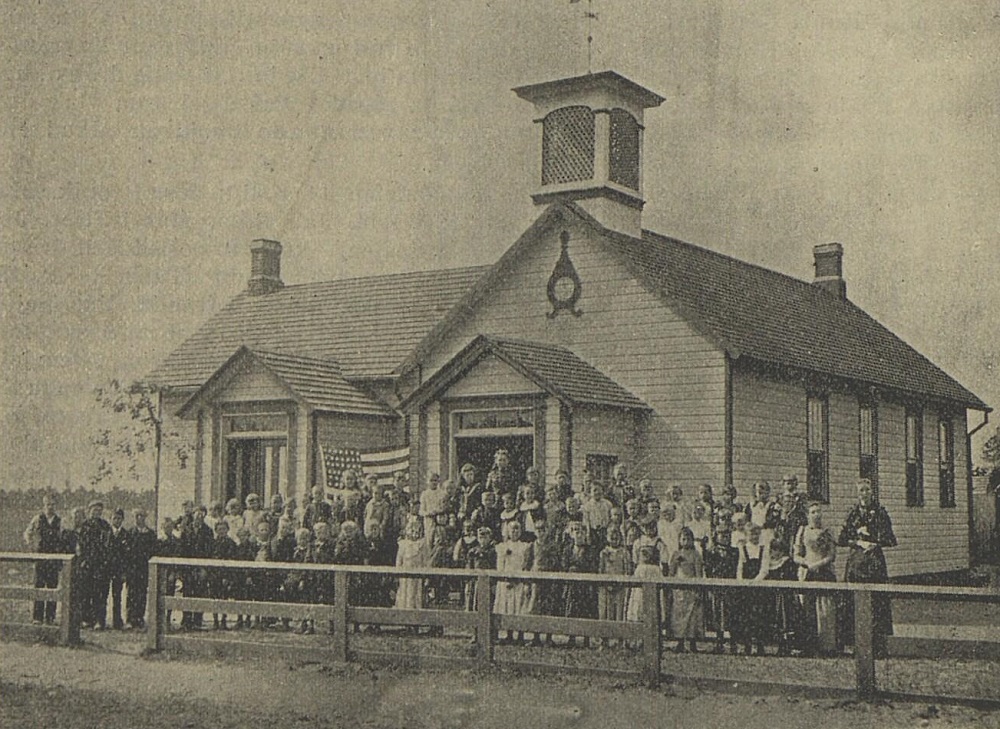

There was a theatrical performance organized on one of these excursions and it made $150.00 which was handed over to the trustees of the settlement. Reverend Clark added his $200.00 which he had collected from the neighboring community to the collection. By the end of the year, the school was built for $600.00 and the first teacher was hired, Miss Elisa Green who was to be paid a salary of $6.00 a week for teaching 48 children.

School building and children with teachers in Bohemia in 1893.

Over time, most of the settlers would work outside the community, mostly at the oil-producing factories at the fisheries at Fire Island. Coming more in touch with the Americans of the island, they were referred to as the Bohemians and everyone began to call the lace where they all lived, Bohemia village. Over time, the name Tábor was simply forgotten.

Between 1868 and 1871, several more Czech families settled in the Bohemia village. Most of these were Czech cigar makers from New York. Eliah Grieswald of Ronkonkoma built a cigar workshop in Lakeland.

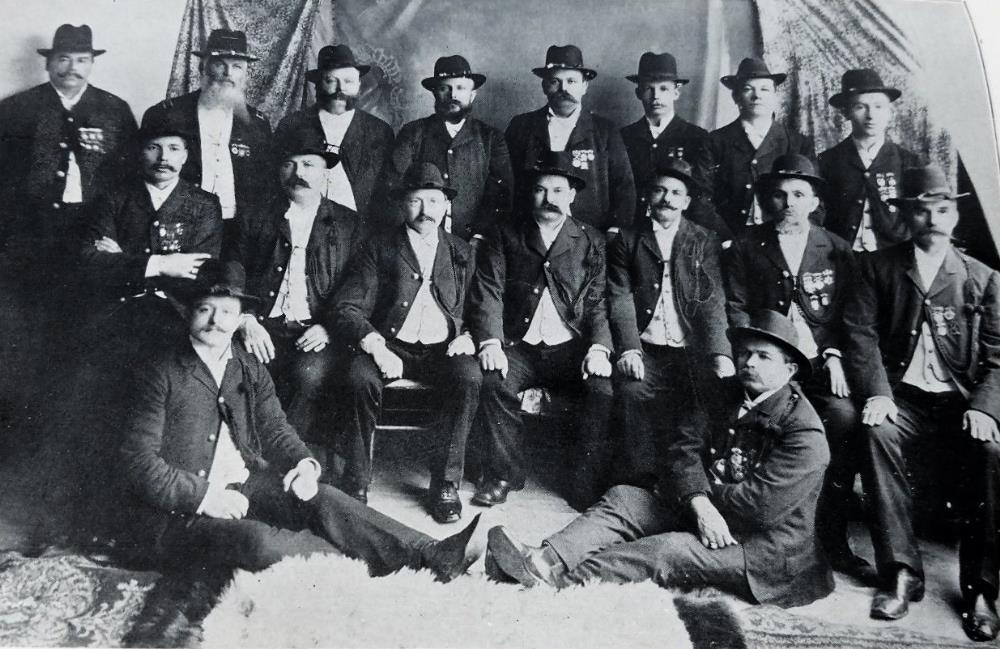

The first official Czech association in the area was the ”Shooting Club” and the first Captain of the association was Josef Jedlička. The association (in the area) lasted from 1868 to 1884.

Photo from the 1874 – 1899 Památník Čes-Amer Střelci Svornost.

In 1872, an economic association (the Czech Farmers’ Club) was founded by by Václav Kroupa, Josef Novotný and Tomáš Bucháčkétn.The purpose of this economical association was to allow members to borrow money with low interest and repayment terms. Loans could be made in 25 cent increments. However there was mistrust of the handling of funds from the beginning and the association was disbanded even though they were a group of twelve who quickly amassed a fortune (at the time) of $5000.00.

From those difficult early moments, the changes which came after were slight by comparison. A house would be built, someone would move in, another would grow tired and move out, but for the most part, the community remained much the same.

By 1883, the Czech periodical Amerikán reported that there were 150 Czechs living in Bohemia. Additionally, they mentioned “In the district of Bohemia, Mr. Jan Vala is a judge, Tomáš Killian and Alexandr Konopík, upholders of the law.”

In 1884, the school building had to be enlarged and a bell was made to ring to the outskirts where new Czechs were settling.

In 1885, Josef Stránský and Schloser founded a Republican club and established a political office in the settlement by the post office. The first postmaster was Josef Nohavec, son of Jan Nohavec. And with the new post office, it was finally necessary to give the settlement a definitive name so that it could be added to the United States postal systems. A meeting was called, and the settlers decided on the name that everyone had given the settlement, the name of Bohemia.

In 1887, on January 3, the “Czech-Slovak Benevolent Association” was founded. And on May 28, 1887, in the Czechoslovak Union of Czechoslovakia No. 139.

The first Czech official who was elected by vote in the township was Josef Šašek, who in 1889 became the towns constable, and from that time the countrymen began to participate in politics.

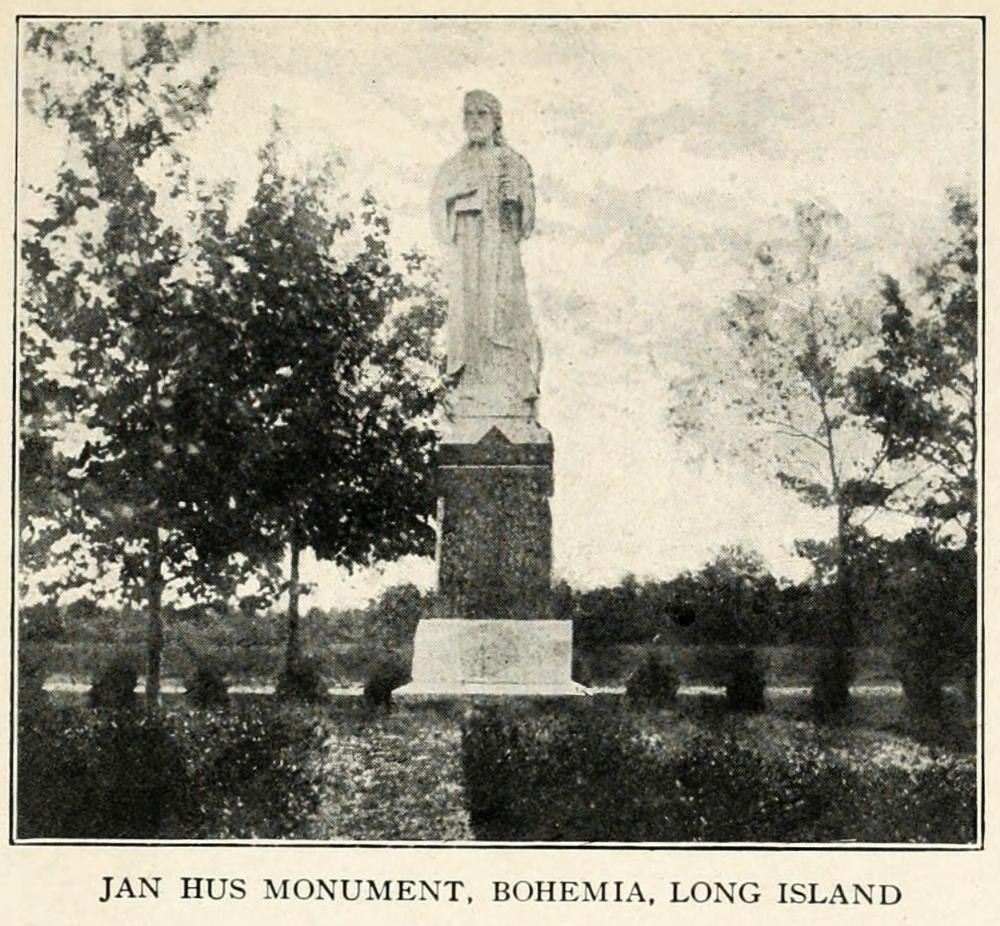

In 1890, the townspeople voted for the construction of a monument of master Jan Hus in the cemetery. Hus is noted for starting the Reformation in the Czech Republic (then essentially the kingdom of Bohemia) about a hundred years before Martin Luther did so in Germany.

The associations in the town collected money and substantial donations were made by Josef Jedlička, Josef Nohavec and Matěj Karšík. In 1892, ads were placed into all Czech American circulars about asking for contributions, and shortly an additional $300.00 was earned.

The 12-foot monument was erected at the cemetery, now known as Bohemia Union Cemetery or Union Cemetery. It was revealed on September 28 with great enthusiasm partly because it came to be by voluntary contributions from Czech immigrants worldwide. It is the first officially dedicated memorial in the United States erected to honor a foreigner. The beautiful work was carved in Vermont by French sculptor, La Valleye.

Two of the three towns founders were there for the unveiling. Jan Kratochvil and Jan Vavra attended. And we could also say that the third founder was present as well. Jan Koula passed away in 1886, and at his own request was now resting at the Bohemia Union Cemetery.

I cannot imagine the tears of joy of they must felt seeing the stature of the most seminal figure in the Bohemian Reformation being raised on the land that had become their second home 38 years ago.

To date, the monument is situated on a hill, near the back central portion of the neatly manicured grounds.

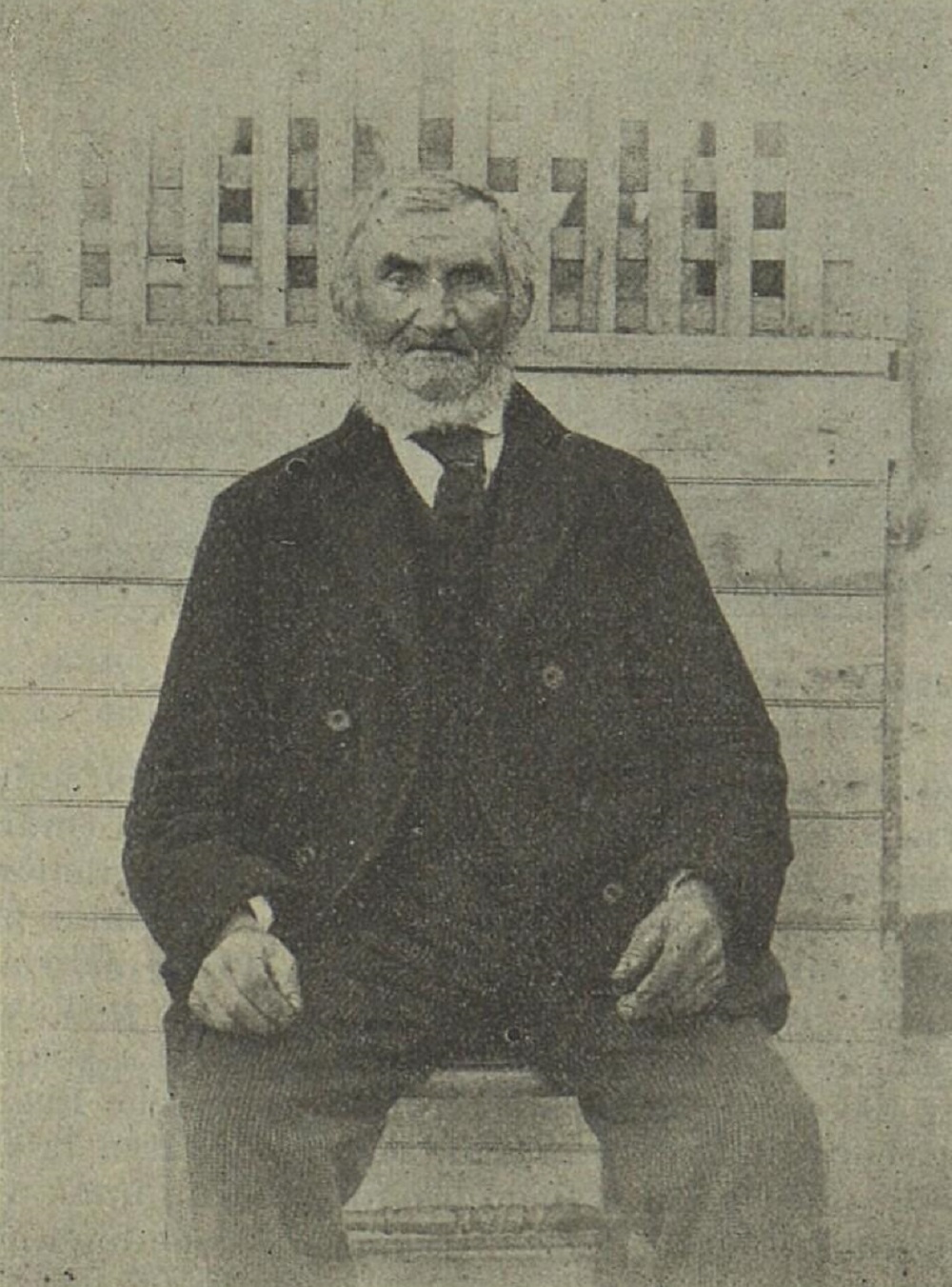

Jan Kratochvíl in Bohemia, Long Island, N.Y.

In 1892, Jan Kratochvíl had built a large public house to be used by the community for the sum of $2000.00. The center was unequalled at the time and was used for meetings, as a theater, etc. In March of 1893, he ensured that a fire brigade was established in the village. As a result of the growth of the settlement, the school district was enlarged and with the help of Antonín Švanda and Josef F. Tůmy, a new election district for Bohemia was allowed.

On November 1, 1893, Jan Kratochvíl died. He was placed in his grave at the cemetery. On June 8, 1893, Vávras wife passed away and that is when the wife of the late Kratochvíl moved away to Riverhead. Vávra then remained the only founder of Bohemia who was still alive and in the township. Surrounded by his children, who under the leadership of M. Karšík were making music, he would enthusiastically applaud. But such moments did not keep him from his vision. Much more was needed and he continued to work on making the town better until his own death.

Bohemia was now a town in America, filled with Czechs and thriving. Interestingly, Bohemia was one of the rare Czech agricultural communities in New York state.

The Other Koula Brother

As more and more years pass, and records get lost, especially when people move around and names are too similar or too unfamiliar, there is room for error. One of these errors was that there was not one Koula, but two. Two brothers, Josef and Jan. What follows is the story of Josef, an interesting addition to the above.

Josef Koula was born on June 3, 1827, in Mnichovice, near Prague, in the former Kouřim region where he trained to be a joiner and also in music.

In 1847 he got married and in 1854 moved with his family and brother John (Jan) to America. They came with Josef Cvigr, Jan Vávra, František Kratochvíl with his parents, Matěj Kumbálek, František Vaněk, Zima, and others whose names are no longer remembered. After a grueling 42-day voyage, the entire group landed in New York. It was November of 1854.

The circumstances at that time were very distressing for immigrants. Work was difficult to come by and wages even smaller. At the time, there were approx. 40 Czechs in New York and the city did not go any further than the so-called “white garden” which was somewhere around what is not tenth street.

The largest part of Manhattan was a wilderness with huge rocks, deep gorges, thick forests, and some farmland.

The barrel of white flour stood at $15, wheat flour at $13.50. A gallon of good whiskey was 35 cents. The only thing that was cheaper then was the meat. He could buy an ox head for 25 cents and sheep heads were available at the slaughterhouses for free. Cuban tobacco was 6 cents a pound, and local tobacco went for 1 cent or a cent and a half.

There was no work to be had, and when a job came available, it was barely paid. Money was very hard to come by. Many compatriots worked on the farms, located on Long Island, for 30 cents a day.

Koula had tried to live in New York, and mostly survived by playing his music, but he was growing more and more hungry so he did not stay in the city too long.

Fortunately, he came from a wealthy family and was able to bring money with him, the sum of approx. $1,000. He decided to buy some land in Long Island. At the end of February 1855, he bought the land where his brother became the one of the founders of Bohemia village, builder of the first house that was built at the settlement.

The family has some interesting memories from the time. Kouda tells how on July 4, 1855, he played in a procession at the congress of delegates from Suffolk County. The whole band consisted of only four men, one clarinet, one trumpet, and two valdhorns. But at least they were paid, and handsomely for the time, a full $5 each. On another occasion, they performed at a ball, where 300 couples danced in pairs, even though there were only three instruments; namely violin, clarinet and tamburine.

In the winter of 1855, Koula left the property where he was with Vávra and Kratochvil and moved to Piermouth, NY, where he worked at Lake Erie Engineering Works. He then went to Lowell, Massachusetts. There he performed various joinery and carpentry work for General Butler. Because of his rcent experience at the engineering works, he was quickly given a job at the engineering workshop where Butler was a shareholder and he continued to work there until the company dissolved. Josef Koula was the first foreigner to get the job there.

In April 1857, Koula moved to Boston, where he settled down permanently, living as before by music and craft. Koula was the first Czech settler in Boston, and later he met a man named Forman from Kolín who was the second Czech there.

By 1862, 146 Czechs had arrived in Boston en route to New Brunswick, Canada. Liking Boston, most stayed and of the 146, seven families left, among them Haman and Pavlovsky. When they lost everything in Canada, almost all of them returned to Boston.

Koula knew from their narrative that there was nothing but misfortune to expect in Canada, and he happened to meet a second expedition who were lured by conscienceless agents, to the Boston station where they were camped out waiting for the train.

He tried to talk them out of going to Canada, but they did not want to believe him. So he brought Haman, whom the emigrants knew, to share his experience. He was surviving in Boston by collecting old rags and mending and then reselling them.

At the time, there were no small coins but instead small paper money, that’s another reason why the collection of clothing was paying off pretty well, because he was fortunate to have regularly found money and stamps in the pockets of discarded clothes. And just about anything could be bought for stamps.

With Haman’s help and illustrated story of his experience, finally the non-believing emigrants decided to give up on the idea of Canada.By this time, all their luggage was already on the ship, and the captain did not want to return any of it to the Czechs. He was on a schedule and was more interested in making money on the fares that all of the Czechs had just cancelled. It was such a mess that a lawyer had to be called and when he showed up, that was when the catain finally agreed to release the Czechs belongings.

The captain admitted that he was afraid of the loss that arose from their cancellations and therefore a collection was made, the result of which was handed over to him, at least in part, to be compensated.

Now what? Suddenly all of the Czechs were in Boston and the existing Czechs had a new large group to worry about. Mrs. Koula cooked huge pots of soups and Mr. Koula was busy trying to get them all work. Some were able to work in a nearby sugar factory. Soon Koula found himself the owner of a hotel and an inn. This decision, perhaps stirred by the desire to help so many Czechs who kept coming.

Some of the Czechs, after saving their money, moved to the West where they could homestead and farm and others remained in Boston. A few still stirred uneasily, wondering where they were supposed to land. So the next project Koula organized was getting them from Boston to New York and then across the water to Long Island. This allowed them to buy flour and other food at cheaper prices. Flour on Long Island was selling for $4.00 a barrel. So why not relocate them there…

He accompanied the Czechs to the place where he built his first house, to Bohemia where he knew a Czech community of good people was growing. This action was good for the immigrants and for the Czechs who were already settled there.

Koula was a skillful craftsman and a resourceful man who always came up with solutions. A testament to this is shown at the time of the Civil War, when there was little work, he began to produce musical instruments which he would sell later on. Koulas family had always centered around music and in the evenings his family and friends partook in singing national songs of the homeland. In rememberance of his brother, he published national songs through the Augustin Geringer ublishing house after his brothers death.

In Koula, we see the best type of an old fashioned, honest, good-natured and patriotic man. A good neighbor who is always ready to contribute, counsel and assist his compatriots. His wife was the kind and noble woman who always supported her husbands deeds and was always at his side until her death.

In 1900, he moved to New Bedford, where he bought a plot of land and built a house just as he had done before in Boston. Josef Koula eventually married a second time and his new wife was also a patriotic woman who was very supportive and active in the lives of their fellow countrymen. The pioneering couple lived their lives for many years of undisturbed health and peace.

More About Bohemia

The earliest known inhabitants of what is today Bohemia were the Secatogue tribe of the Algonquian peoples.

The area was founded as Bohemia in 1855 by Slavic immigrants who were the first Europeans to settle there in large numbers. These migrants came from a mountainous village near Kadaň in the Central European Kingdom of Bohemia, which is the town’s namesake (Kadaň is located in present-day Czech Republic).

Their pilgrimage coincided with a wave of Bohemian nationals emigrating to the United States, many of whom embodied the free spirited and enlightened lifestyles synonymous with Bohemianism. They had taken part in the widespread revolutions against autocratic rule that had shaken Europe in 1848 and came seeking a new life in the United States.

Work was hard to come by in New York and many of the men tried to support themselves as street musicians. An important contribution they made to the development of Long Island was adding their rich Central European folklore to the local culture, a nice compliment to the also rich oral tradition of the native people. Many of the first homes they built are located on the town’s avenues and are distinguished by their cross gable roofs.

Besides the Czech settlement in the city of New York around 1850, there were other and more smaller Czech settlements in the state. In Buffalo, several Czech families lived there in 1852 but these later moved to the west. There were dozens of Czechs in Queens County on Long Island; Bohemia, as mentioned here; and around Rockland Lake, where by 1855, there lived 35 Czech families.

The Slavic immigrants came to Bohemia with excellent cigar-making skills. There were once several cigar making factories in the town and the industry provided a living for many of the residents. Two notable cigar factories were Albert Kovanda’s factory, located on the corner of Lakeland and Smithtown Avenues, and the M. Foster Cigar Factory, located at Ocean Avenue and Church Street.

By the late 19th century, there were eight cigar factories in the Bohemia and Holbrook areas. The local cigar industry continued until the 1930s when mechanized production did away with the need for hand manufacturing. No cigar factories remain today.

Over the years, there had been a number of attempts to change the name of Bohemia, which some people felt was too tied to one ethnic group. They felt this was keeping new people and new businesses from coming to the town. Proposed new names have included: Sayville Heights, after the town immediately to the south; Lidice, after a Czech town destroyed by Nazi troops during World War II; and MacArthur, after the airport built in the 1940s (the airport is named for famed American General Douglas MacArthur). None of the efforts to change the name received enough public support to be finalized.

For 100 years, Bohemia remained a very small village most of whose residents were of Czech descent. With the development of all of Long Island after World War II, Bohemia also grew. At the time of the centennial in 1955, the population was about 3,000.

The Czech influence remained strong for many decades. But by the 1960’s, the ethnic mix became more diverse. According to the 1970 census, Czechs were the fourth-largest ethnic group in Bohemia. By 1990, they were sixth.

Today there about 11,000 inhabitants from many national and ethnic backgrounds an Czechs represent less than 5 percent of the Bohemia population.

The Bohemia Union Cemetery

The Bohemia Union Cemetery was officially established in 1873 and is located on the south side of Church Street in Bohemia, between Walnut and Smithtown Avenues. It continues to reflect the heritage of those who established the town in the middle of the nineteenth century.

Jan Hus monument at the Bohemian Union Cemetery, Bohemia, Long Island, N.Y.

Visiting the cemetery, you will notice that some of the headstones are written in the Czech language and many others are etched with Bohemian surnames, serving as reminders of the population that gave the area its name.

You may enjoy hearing this story about the night across the street from the cemetery.

Bohemia Today

Dedicated to preserving the rich heritage of the hamlet, the Bohemia Historical Society (BHS) was founded in 1984. They are a non-profit local organization pursuing their goal through their educational programs, slide presentations, involvement in community activities, a newsletter, their website and their museum. The museum was officially opened on April 26, 2009, and it houses a number of exhibits depicting life in the early days of Bohemia, a photograph collection, and a book collection that includes many historical Czech manuscripts. Additionally, the building serves as the society meeting place.

These days there are stories of hauntings and ghosts and sadly, less than 5% of the populations identifies with a Czech background.

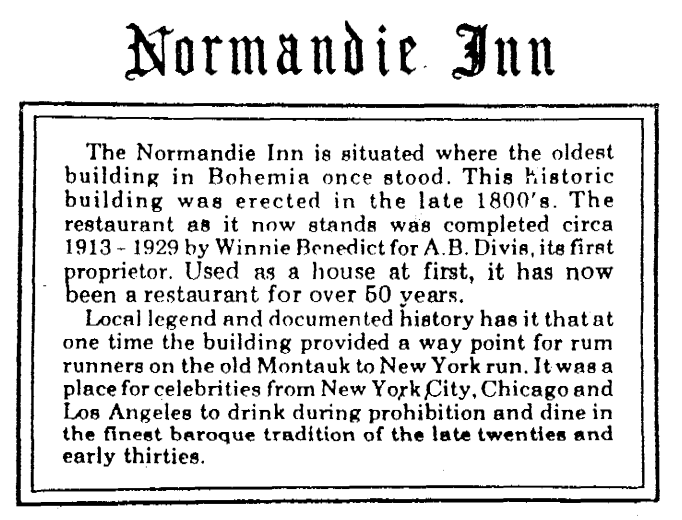

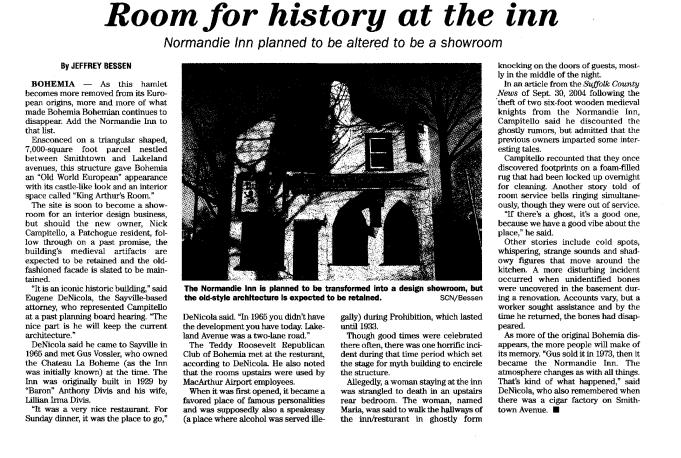

Let’s take a look at the Normandie Inn located at 1500 Smithtown Ave, Bohemia, NY 11716.

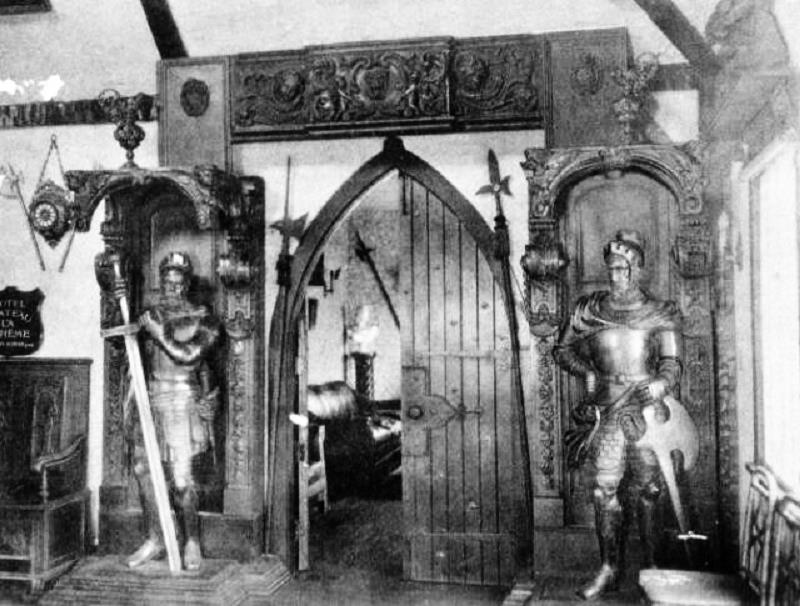

First known as Chateau La Boheme, these photos are from the late 1920s early 1930s.

Date of initial construction: 1913-1920.

Architect: Hoberg.

Builder: Winnie Benedict.

Originally it was supposedly built as a residence “for a Czech baron in the 1920s”, according to a 2008 Long Island Business News article. Apparently Rudolph Valentino stayed there as well.

Prohibition was from 1919 to 1933 and that Valentino died in 1926. It’s believed it’s older than the 1920 timeline – all the way back to the late 1880’s.

The Bohemia Historical Society lists its first official owners as Lillian and Anthony Divis.

I found a grand opening announcement in The Suffolk County News., September 06, 1929, Page 6, Image 6. It mentions an art gallery as well as the proprietor being names Ambrose B. Davis.

Later, on April 01, 1955, Page 15 of The Suffolk County News:

As you can see, at this time, August and Ethel Voss were doing business as Hotel Chateau La Boheme.

The restaurant and inn’s early claim to fame was an elaborate dining room that featured a 500-year-old handmade fireplace and two sets of armor that dated back to the 1600’s.

Photo source: Bohemia Historical Society

Before the restaurant was built on the property, there was a cigar factory there which burned down sometime in the early 1900s.

Afterwards, the lot was sold to Anthony Boris Divis, a Czech immigrant, and art dealer who claimed to be descended from nobility. The Divis family operated the restaurant and inn up until 1960 when it was sold and passed through several owners before being abandoned in 2004.

The Moravian style building he constructed, seems befitting the personality of a man who claimed to have been a former Austrian army officer nicknamed “the Baron”, who wore a monocle and had hand-kissing manners.

In the late 1920s, he used the building to sell art and antiques, but during prohibition, he sold alcohol.

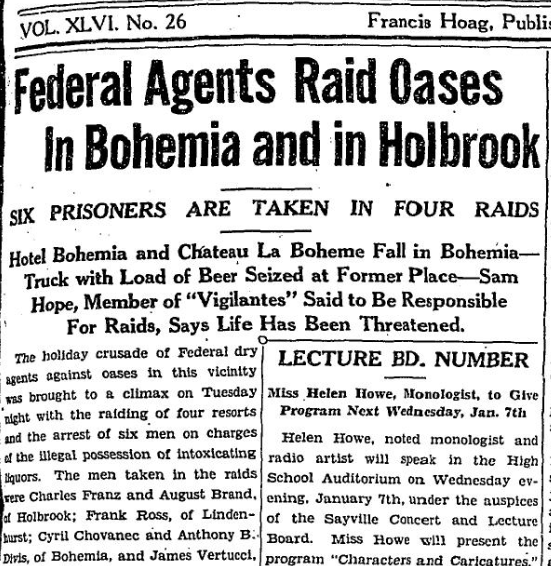

The Chateau La Boheme, transformed into a speakeasy during the prohibition and disturbed some in the community.

A Ronkonkoma “Vigilante committee,” fed up with the “menace of the intolerable speakeasy conditions,” tipped off authorities.

Federal agents raided Chateau La Boheme in 1931 and then again the following year. Mr. Divis and several others were taken into custody on both occasions.

The Suffolk County News from January 02, 1931, Page 1, Image 1 shows a little bit of trouble for the hotel:

You can read the entire article here.

Rum runners from New York City to Montauk and back to Manhattan, would stop there. Celebrities were supposed to drink and dine there during that time as well. This was during its popular run as the Hotel Chateau La Boheme.

The Suffolk County News, In the July 12, 1940 edition, Page 12, had the following:

“Chateau La Boheme Plans Sale of Fine Antiques – There is a unique and appealing charm about the Hotel Chateau La Boheme, on Smithtown Avenue at Bohemia. Established 10 years ago, the place is known to the public as a quality center. Miss Irma Andrews became manager one year ago and has effected many important changes and improvements to brighten up the place and increase its advantages. She is charming in personality and competent in the managerial work. Bohemian atmosphere and foods with American dishes also provided, attract a wide patronage. This hotel has a dining room which will accommodate 200 people. Parties and other special occasion events are welcomed. There are also 10 cleanly, comfortable guest rooms. A splendid collection of old-world antiques, particularly from Czechoslovakia is offered for sale.”

The Chateau La Boheme was sold in 1952 to August Voss, a German, who along with his wife, ran the restaurant for about 21 years. Although the restaurant continued to change ownership, the building substantially retained its medieval castle-like décor and ambiance. The wooden plank doors, chandeliers, ornate wooden trim, and suits of armor remained through the various ownership changes and its last days as the Normandie Inn.

Today its one of the 13 of Long Island’s most creepiest and prolific haunts.

The Gothic-style structure on the corner of Smithtown and Lakeland has been boarded up since 2004 and is currently once again up for sale.

One article online says that for a while Ritchie Blackmore of Deep Purple used to play Renaissance music there.

The Hotel Chateau La Boheme (and later, Normandie Inn) has been rumored to be haunted by a woman named Maria (other sources say Sarah), a young woman who was allegedly strangled to death in the upstairs back bedroom during the time it was a speakeasy.

Visitors have heard walking in the hallways at all hours of the night and knocking on visitors’ doors when it was a hotel. Guests have reported that someone would knock on their doors at night and when they answered… no one was there, but they felt an ice cold breeze!

Others have heard strange whispering sounds, like that of a young woman and have seen shadow people lurking around the premises inside of the hotel and on the outer grounds of the hotel property.

There have also been reports of cold spots and other apparitions by ghost hunters who have gone to check the house based on the rumors.

Another article states, “Over the years many staff members and guests reported that the room in which Maria was allegedly killed was host to myriad paranormal phenomena including cold spots, unexplained footprints and the slamming/opening of doors and windows.”

In fact, ask anyone in town and they will share that a lot of people have heard that the place is not only haunted, but cursed. That everyone who owns it has tragedy strike them or their families.

The most recent owner has said that the previous owner informed him that long-silent room service bells once began ringing without explanation and footprints once appeared on a just-shampooed rug in a locked bedroom.

It has also been said that there was a pile of bones found in the basement of the Inn during renovations either by the hotel employees or by the workers. The claim that they were not sure if they were animal bones or human remains, but when they went for help to find out more about the bones, when they returned the bones were missing and never found. Are these the bones of Maria’s strangled body, no one will ever know?

From the 1970’s to the 1980’s the place was reportedly a hangout for bikers. I am not sure why. It does not have the look of a place you imagine a bunch of Harley Davidson riders hanging out. But the curse affected them too. Supposedly some of the bikers who liked to go there would end up dying, either in the area or some place else. I guess over time, the others caught (and the rumors grew) that the place was bad luck and even the tough bikers stopped going there.

I wonder who Maria was and if she was Czech. If the story is true, I wonder how she met her tragic fate (a friend, a stranger?) which has sealed her spirit forever into the structure or location. The building is now ransacked, gutted and run-down and many in the community say it’s an eyesore and they wish it was torn down.

In 1990 a man named Richard Freida was listed as the property owner.

In late 2003/early 2004, the Normandie Inn folded, and the building was purchased by an unnamed company (the business was not listed on any public record even though the video does mention a name, Campitello) with the apparent intention of using it as an office.

Strangely enough, there is no record of any construction or remodeling since then.

But, I did locate this article, which solves the “Baron” question, and dates the building as being built in 1929.

The Suffolk County News., March 29, 2007, Page 5:

At present the building remains boarded up, watching over its intersection as a foreboding reminder of its mysterious history.

Does anyone have any further information on the place or anything else to add – if so, please use the comments section below. Thank you!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Become a friend and get our lovely Czech postcard pack.