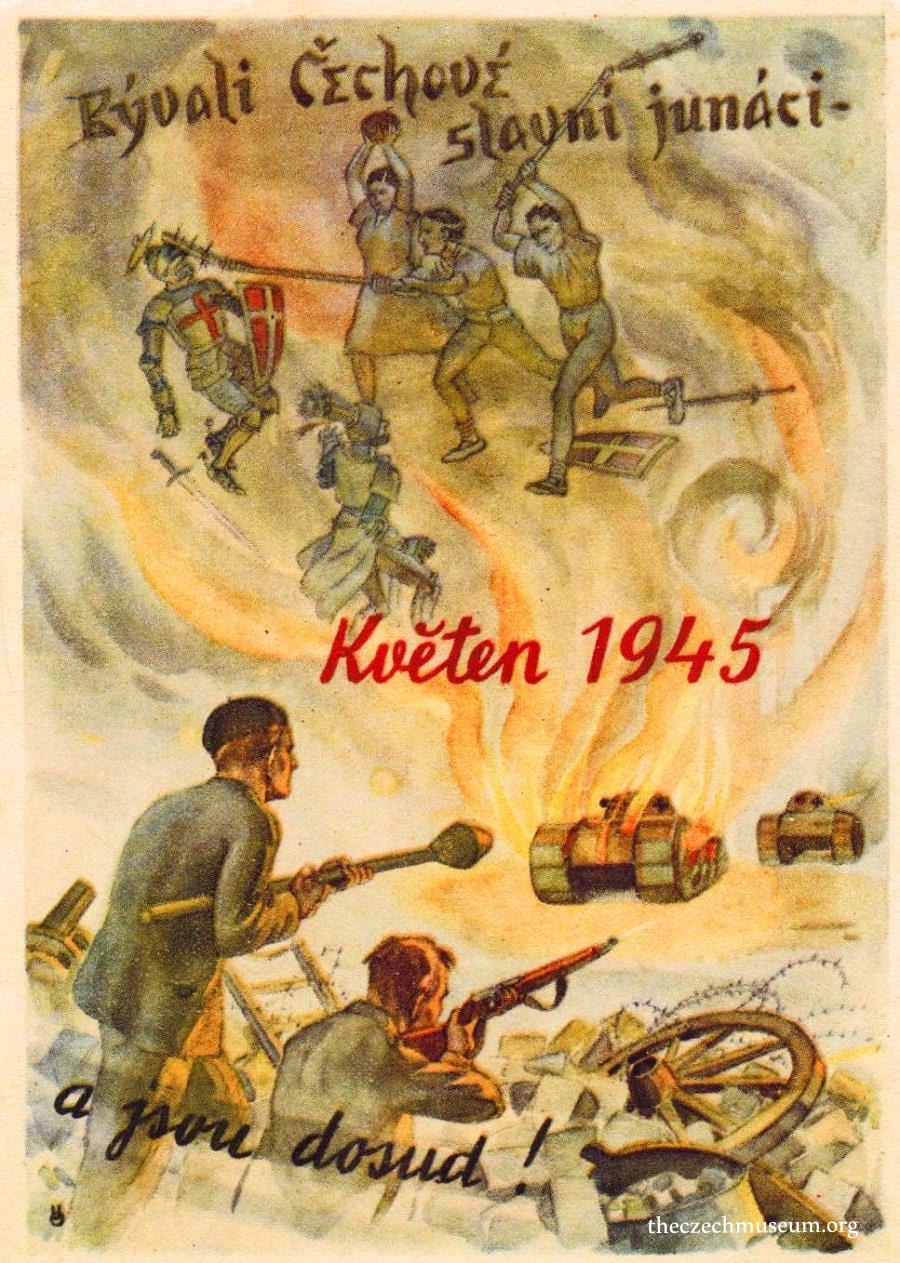

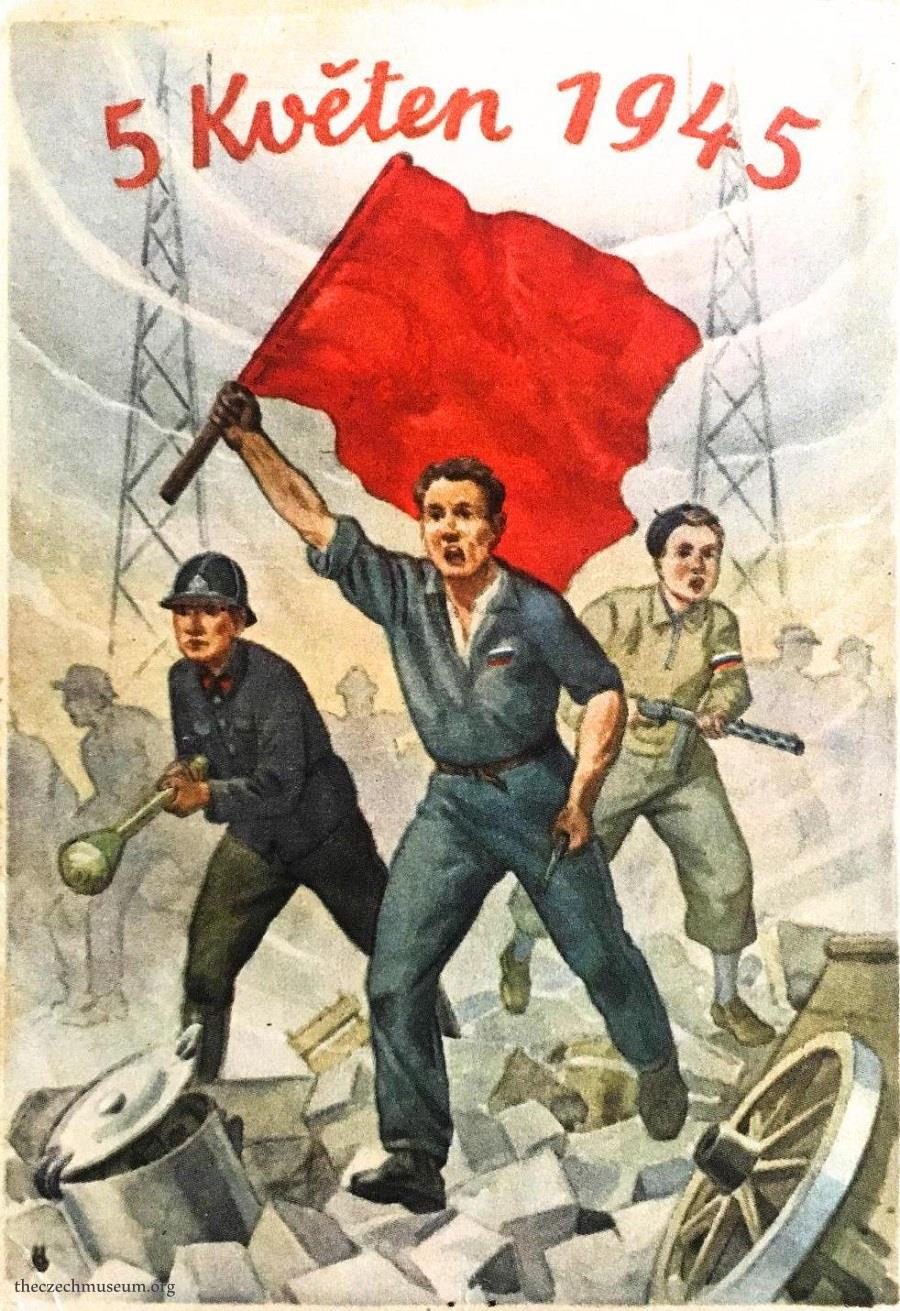

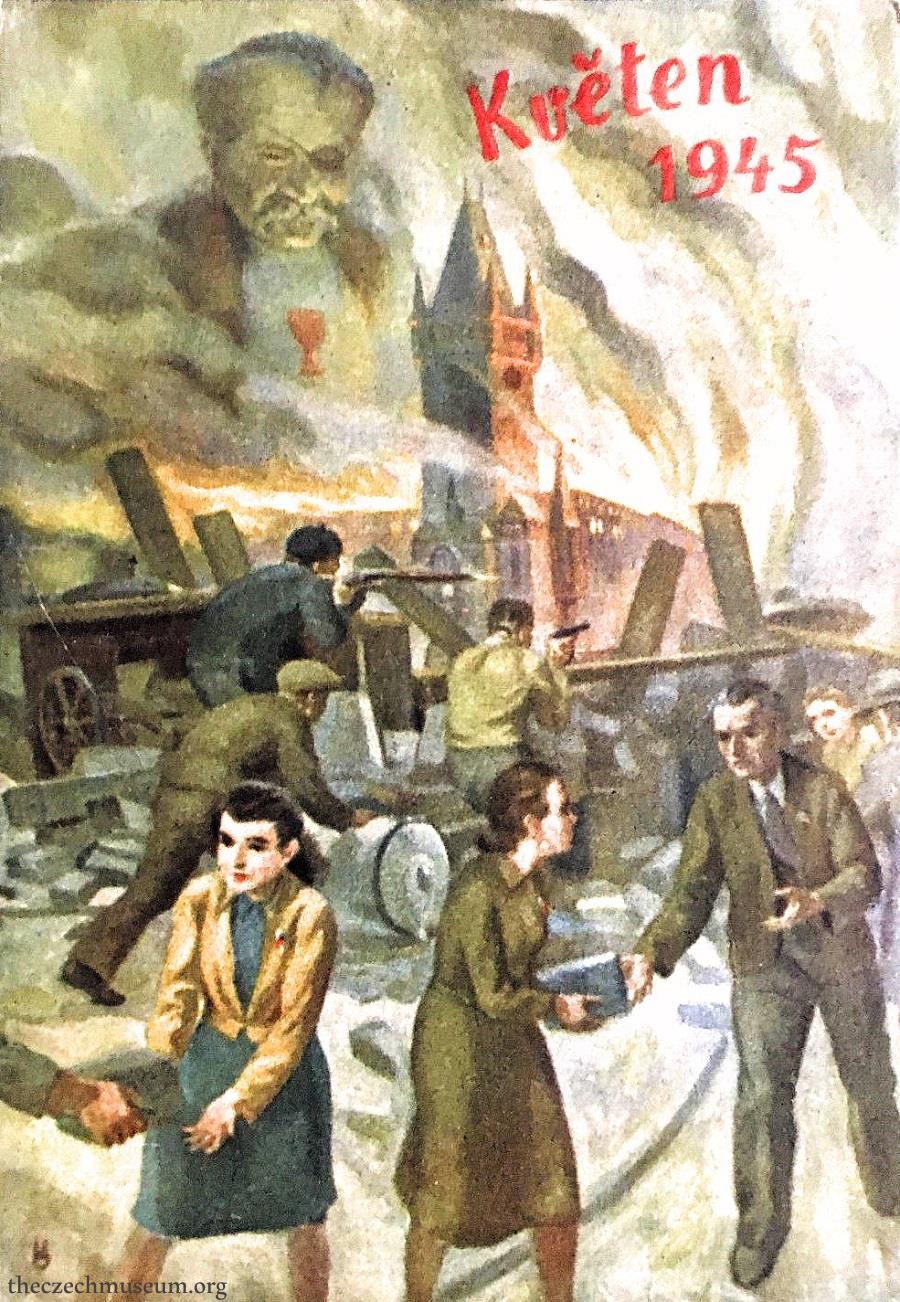

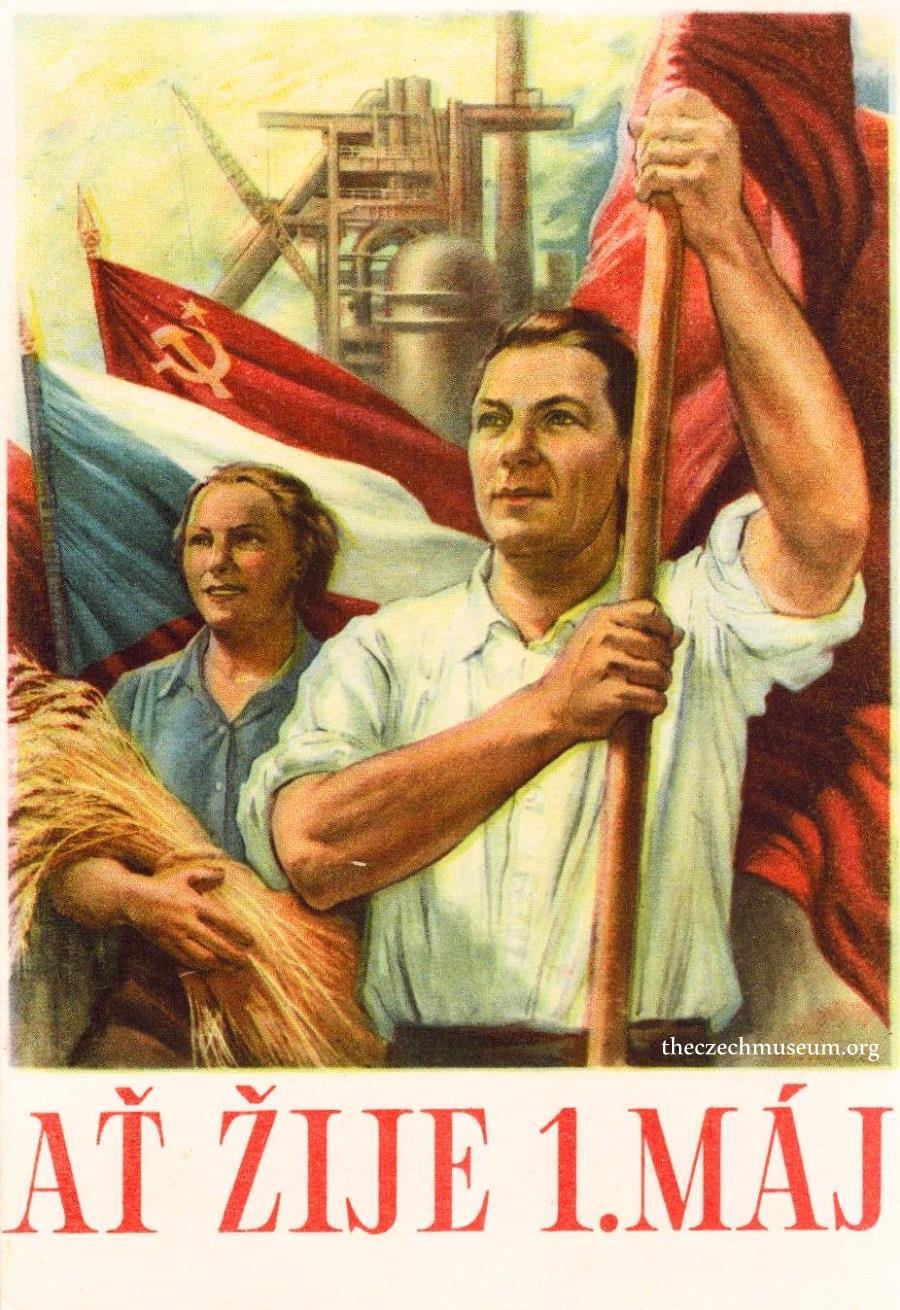

Today we are looking at 1945 Soviet propaganda posters for the liberation of Czechoslovakia as well as learning a bit about the Prague Uprising (aka Pražské povstání), an attempt by the Czech resistance to liberate the city of Prague from German occupation during World War II.

“This is Prague! Americans and English, help us” We need guns. There are too many Germans. Send us aeroplanes and tanks. Americans before Plzeň. Send us aeroplanes too! The Germans are coming from south, north, west and east. Help us! Help us!”

The liberation of Czechoslovakia from German rule over 60 years ago left behind a number of controversies and puzzles, an important one is how much of a part the Russians actually played.

In the spring of 1945, rumors were swirling that Allied forces nearing the city. The American Army was approaching from the west. The Soviet Army was moving in from the east. Groups of Czech fighters began the “battle of the rails”, in which they sabotaged railroads, train stations, German trains, and highways.

Between April 30 and May 1, Karl Hermann Frank, the SS Group Leader, aired a radio broadcast in which he promised violent retribution against any possible uprisings. Frank knew how to do it; he was responsible for organizing the horrible events in Lidice and Ležáky in 1942. He ordered civilians to stay out of the streets, and ordered German soldiers to fire upon anyone who refused to obey his orders.

On May 5, Czech police officers burst into the radio station at Vinohradská Street and battled with the SS soldiers who were already occupying the building. The announcer, hearing the sounds of fighting, began to encourage the Czechs to rise against the Nazis.

“Hello, hello, hello! This is Prague calling London. Once again we repeat what I have already said three or four times. The Germans did not keep their promise. Prague is in great danger. The Germans are attacking with tanks and planes. We’re calling urgently our allies to help. Send immediately tanks and aircraft. Help us defend Prague.”

Resistance fighters in other parts of the city took over the Gestapo and SiPo headquarters. Civilians finally removed the hated German signs, and began to attack and disarm the Germans (at extreme risk of being shot). Barricades were built in the streets. Utilities were cut off, disabling German communication. The Nazi puppet mayor, Josef Pfitzner, panicked and stated allegiance to the Czech National Committee.

It didn’t take long for German forces outside Prague to mobilize in aid of their comrades in the city. On May 6, the Germans retook the main radio station, but Czech partisans continued broadcasting from another base.

“Do not let Prague be destroyed. We don’t know how long we can hold out. We are hoping for the best – that English, American or Russian troops will reach us in the next few hours. It has to be very quick and very soon. Good night!”

German bombers flew in on May 7 and bombed the city, causing the destruction of most of the Old Town Hall; the centuries-old building was almost completely gutted, and had to be torn down. The top of the tower was also destroyed, and damage was caused to the famous Astronomical Clock. The Germans’ superior firepower gradually overwhelmed the Czech fighters, whose ammunition was insufficient.

Much to the surprise of both sides, a division of the Russian Liberation Army (ROA), which was strongly opposed to Communism and had been allied with the Third Reich, suddenly changed tactics and pitched in against the Germans.

“Prague calls the Red Army! We need your help!”

The Army had the ammunition and tanks that the Czechs so badly needed, and was instrumental in saving the city center. Unfortunately, the leader of the division, Andrei Vlasov, feared that the Czechs would betray him (some of the Communist Czechs had already captured some of his men to hand them over to the Red Army), and the division pulled out and headed west. (Vlasov and several other leaders of the Army were later captured and handed over to the Soviets; they were hanged for treason the following year.)

On May 8, with Allied troops approaching from west and east, the Czechs negotiated a cease-fire with the Germans. The situation was now critical; the Czechs lacked the machinery and the weaponry to continue fighting the Germans, and the city’s Old Town was in flames. Part of the cease-fire was a guarantee, from the Germans, that the city would not be harmed further.

The Czechs knew that, with help on the way, the cease-fire would be far more beneficial to them than it seemed on the surface.

A previous agreement between American and Russian forces stated that the Red Army would be the one to liberate Prague; however, some American Army forces had come as far as the suburbs of Prague, and some negotiators persuaded General Toussaint, commander in charge of the German forces, to agree to the cease-fire.

By the time the Red Army rolled into Prague on the morning of May 9, 1945, the city had as good as liberated itself.

The city had been saved; its currently UNESCO – protected monuments were, for the most part, intact. And the war was, now, finally over.. As the tanks came down the hill towards the city center, they were joined by a jubilant radio reporter.

“We are coming down the winding hill from the Castle. On the left is Klárov, on the right Hradčany, and before us a city is spreading out whose joy reaches the stars. At this moment the Red Army has liberated Prague.”

The bloodthirsty Frank, now stripped of any and all power, surrendered to the American Army in Pilsen the same day. In March and April of 1946, he was tried in Prague for war crimes. 5,000 people turned out to view his execution by hanging in Prague’s Pankrác Prison on May 22, 1946. His body was thrown into an anonymous grave in the city’s Ďáblice Cemetery.

The exact numbers of those died in the Prague Uprising are still not completely known.

What is known from looking at these propaganda posters is that Russia took all of the credit for the liberation in the years that followed.

On the records that do exist, 1,694 Czechs were killed; an additional 1,600 were badly injured. The ROA, with its last-minute intervention, suffered casualties of approximately 300 men (not counting those who were later handed over to the Soviets). About 30 soldiers in the Red Army lost their lives.

After coming to power in 1948, the communists claimed all credit for the uprising, persecuting noncommunists who played a significant role, such as Czech Army officers, policemen, scouts and other young people, according to author and historian Jindrich Marek.

Jaroslav Hrbek, of the Contemporary History Institute in Prague, says a key factor was the intervention of Vlasov’s Army, a group formed by renegade Soviet General Andrei Andreyevich Vlasov. After being captured by the Nazis in 1942, Vlasov professed that he hated Stalin and persuaded the Germans to allow him to form 50,000 prisoners of war from the Soviet Union into a force that would fight the Red Army. But Vlasov turned on his Nazi masters and, after pleas for help from uprising leaders, his army marched to Prague.

Without Vlasov’s troops, “the uprising would have collapsed. Vlasov’s army was well organized and, unlike the uprising forces, had its own artillery,” says Hrbek.

Marek, however, says Vlasov’s army “offered a lot of help, but to say that they actually saved the uprising is as extreme as saying that it [the uprising] was entirely conducted by the communists.”

After the uprising, Vlasov’s men handed themselves over to the Americans – who then handed them over to the Russians. By doing this, the U.S. commanders were condemning Vlasov’s troops to a cruel fate. The handover of Vlasov’s men to the Soviets is known as one of the most extraordinary betrayals of history.

“The officers ended up sentenced never to see daylight again – to be worked to death underground in mines in the Urals,” adds author and filmmaker, Stephen Weeks.

Today, visitors to Prague will see plaques everywhere, but especially in the city center, bearing names and dates. These plaques commemorate the men and women of the city who lost their lives in the Prague Uprising, and are placed at the locations where the deaths occurred. The dates of the person’s birth and death, if known, are engraved on the plaques. A few of them simply read, “To the unknown fighter”.

Quotations Source: Radio.cz, Information Sources: The Prague Post and Private Prague Guide.

“Calling all Czechs! Come to our aid immediately! Calling all Czechs!” – read more about the Prague Uprising.

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Become a friend and get our lovely Czech postcard pack.