People visiting the Czech Republic and Slovakia expect to see what the travel magazines show us; the castles, ancient bridges, cobblestone streets, stunning cathedrals and more. What they often don’t realize is that millions of people who live there do not all live in castles and luxury flats. In fact, a third of the population live in something called Paneláks.

Panelák is a colloquial term in Czech and Slovak for a panel building constructed of pre-fabricated, pre-stressed concrete, such as those in the former Czechoslovakia and elsewhere in the world. Panelák [plural: paneláky] is derived from the standard Czech: panelový dům or Slovak: panelový dom meaning, literally, “panel house / prefabricated-sections house”.

The term panelák is used mainly for the elongate blocks with more sections with separate entrances – simple panel tower blocks are called “věžový dům” (tower house) or colloquially “věžák”. The buildings remain a towering, highly visible reminder of the Communist era. The term panelák refers specifically to buildings in the former Czechoslovakia. However, similar buildings were built in other Communist countries and even in the West.

Panel buildings may refer to buildings of one of the following types:

- Built of structural insulated panels

- Built of pre-fabricated concrete blocks, named differently in various countries. Large Panel System building, often called Plattenbau from German or Panelák from Czech and Slovak, Blok from Polish or Panelház in Hungarian.

- Panel buildings can be either frameless (column-less), or the panels can be fitted to:,

- Timber-, steel- or reinforced concrete-framed buildings,

- over common blockwork,

- or over existing masonry products

Paneláks resulted from two main factors: the postwar housing shortage and the ideology of Czechoslovak leaders. Planners from the Communist era wanted to provide large quantities of affordable housing and to slash costs by employing uniform designs over the whole country.

They also sought to foster a “collectivistic nature” in the people. In case of war, these houses would not be as susceptible to firebombing as traditional, densely packed buildings.

Mass Produced Monstrosities

In comparison to pre-war apartment buildings, paneláks can be truly enormous and quite ugly. Some are more than 100 meters long, and some are more than 20 stories high.

Some even have openings for cars and pedestrians to pass through, lest they have to go all the way around the building.

They were built at a low cost, quickly. No one was thinking of a pretty neighborhood at the time. Construction did not involve urban planning and there is no visible conceptual link between these early buildings and their neighborhoods.

Urban planning in the Soviet Bloc countries during the Cold War era was dictated by ideological, political, social as well as economic motives. Soviet-style cities are often traced to Modernist ideas in architecture (such as those of Le Corbusier and his plans for Paris). The housing developments generally feature tower blocks in park-like settings, standardized and mass-produced using structural insulated panels within a short period of time.

The financial resources of all eastern European countries, after nationalization of industry and land, were under total government control. All development and investment had to be financed by the state. According to communist ideology, the first priority was building a socialist industry.

Between 1959 and 1995, paneláks containing 1.17 million flats were built in what is now called the Czech Republic. They house about 3.5 million people, or about one-third of the country’s population.

Prague’s “Hidden” Suburbs

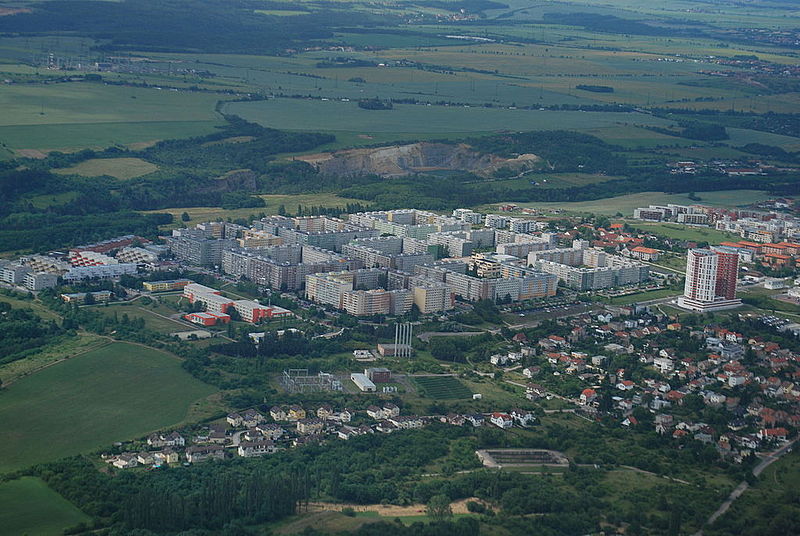

The tourists don’t often see them, but in Prague and other large cities, most paneláks were built in a type of housing estate known as a sídliště. Such developments now dominate the suburbs of Prague, Bratislava and other towns. The first sídliště built in Prague was Petřiny in the 1950s; the largest in Prague is Jižní Město (about 100,000 inhabitants), with 200 buildings built since the 1970s.

Prague-Kamýk, the Czech Republic.

The largest concentration of paneláks in the former Czechoslovakia and central Europe can be found in Petržalka (population about 105,000), a section of the Slovak capital of Bratislava.

The city of Most is known for having a dominant share of people living in paneláks (approx. 80%). The historical city was torn down due to the spread of coal mining and the majority of its population was moved into paneláks.

Undignified Rabbit Pens

Many people criticize paneláks for their low design quality, mind-numbing appearance, second-rate construction materials and shoddy construction practices. In 1990, Václav Havel, then president of Czechoslovakia, called paneláks “undignified rabbit pens, slated for liquidation.” Panelák housing estates as a whole are said to be mere bedroom communities with few conveniences and even less character.

However, paneláks are not universally detested. Some panelák housing estates were designed by Czech architects who aspired to follow the tradition of pre-war Czech modern architecture, notably functionalism. Despite unfortunate cost-saving changes during construction, some of those panelák estates do not fit the critique above.

Amenities and Characteristics

Some housing estates do have other facilities, such as shopping centers, schools, libraries, swimming pools, and cinemas. Also, architects sometimes made an effort to make the buildings distinct, by mixing various types of panelaks, for example, or by using different colors. Well-designed housing estates also have some environmental advantages. By leaving wide spaces between buildings, designers created large green spaces and parks, which are lacking in many prewar Czech neighborhoods. In some places, paneláks were an improvement in sanitary conditions.

Home to the Large Middle Class

Unlike government-built housing estates in places like the United States and United Kingdom, paneláks today remain home to a mix of social classes, with the middle class prevailing (according to sociologist Michal Illner from the Czech Academy of Sciences). Thus, there is little social stigma associated with living in a panelák. Many apartments are well-appointed inside; there is even a home magazine, Panel Plus, aimed at the millions of panelák-dwellers. Among the important people living in a panelák is Czech ex-Prime minister Jan Fischer.

Panelák estates, especially in big cities, are the obvious first targets for builders of telecommunication networks, as the housing estates combine a high concentration of people with easy access to underground and in-house spaces for cables. Panelák housing estates are usually the first neighborhoods with access to cable tv, WiFi network coverage, cable-modem service, DSL and other telecommunication services.

The cost of replacing of paneláks in the short term would be well beyond the means of the Czech Republic or Slovakia. Nonetheless, the decay of many paneláks remains a serious problem requiring the attention of authorities in both countries.

A view in the background of some of the concrete panel apartment houses or paneláks that were built for state housing during the communist era. In Bratislava, there are estimated 860,000 such dwellings of which 600,000 are in dire need of repair. The first ones were built around 1955 and they only have an estimated lifespan of 60-80 years so a massive housing investment is underway to both re-furbish and build new housing stock.

Many Czech sociologists have expressed concern about the social development of panelák housing estates. The most endangered would be those lacking facilities other than “sleeping blocks” and with a bad connection to business and commercial centers. Some people fear that with the growth and deregulation of the housing market, the middle class may flee to other locations, and such panelák estates may become refuges for the poor or ghettos for minorities and immigrants.

Some local authorities are making significant efforts to prevent this scenario by changing bedroom communities into multi-functional urban neighborhoods. This may include support for the construction of missing facilities, such as shopping centers or churches. Governments may also invest in improving transport accessibility, as with the new light rail line to Barrandov in Prague.

Jdi do háje

Telling someone in Czech ‘Jdi do háje’ is like telling them to go fly a kite or to stuff it. I never even knew a place called háje existed and always thought it was this expression. Then one day in Prague, I got on the metro and say that the last stop was háje. I rode the metro all the way to the end, just to see what a ‘háje’ looked like. This is what I saw…

The Czech village of Háje was founded in 18th century, and became part of Prague in 1968. Now it is its own cadastral area, part of the administrative district Prague 11 (Prague 4). Its area is less than one square mile (0.91 sq mi) and its population is 23,528. Imagine cramming almost 25,000 people into less than one square mile and you will begin to understand what panel buildings were designed to do.

Háje was founded in 18th century and historically it was part of Hostivař. Háje became part of Prague 1968. The building of Jižní Město (South Town in English), the biggest housing estate in the Czech republic started in Háje in 1971. Most of old village of Háje was demolished and replaced by panel buildings (paneláky).

The Chánov Nightmare

The Chánov housing estate in Most, Czech Republic, is an example of what planners are trying to avoid. In the 1990s, middle-class residents moved out in response to an influx of Romany immigrants. Many of the remaining residents lacked jobs, money, education and the social skills needed for life in an urban environment.

The water was cut off due to unpaid bills; elevators stopped working; and garbage piled up in mounds.

For a period of time, the Czech republic aired an extremely watched television series entitled Most!. The series was filmed in the ghetto of Chanov in what culminated in a column of shiny limousines. MEPs, ministers and regional politicians all stepped out, promising the locals to clean up the city and solve their problems. But now that the spotlight of the show has faded, the politicians have disappeared and the people in the ghetto continue to live without electricity, heat and hot water in the depopulated houses that they destroyed themselves, leaving only bare concrete walls.

It’s a problem difficult for Czechs because the population in the ghetto is mostly Romani gypsies. You can read more here (in Czech).

An interesting documentary (which shows rare footage of Most before its destruction) can be seen below.

It is only in Czech language.

The prefabricated towers have served over one-third of the population of the Czech Republic for over 50 years. They are no longer just communist solutions to an industrial life. They have transitioned into a new age and the attitude of panelák inhabitants to their buildings also vary. According to Illner, “people get used to living in paneláks”.

Many panelák flats are now the property of their inhabitants and whole buildings are managed by syndicates of flat owners. Many buildings have been renovated, often with the support of local governments. Renovations have often included the installation of thermal insulation for energy efficiency and new coats of colorful paint.

Aerial view of Velká Ohrada Panelaks from north east. Malá Ohrada in the foreground.

Trams, buses and metro lines make getting to and from the city center quick and easy and these days, a lot of the inhabitants are happy to be away from the busy tourist center Prague is rapidly becoming.

If this subject interests you, you will be very interested in the this article, complete with photographs in which he discusses how Czech prefab housing gets museum billing.

We also recommend you see the artwork at the this link. It brings a smile after viewing all of these photographs of this mass housing…

* * * * *

Thank you in advance for your support…

You could spend hours, days, weeks, and months finding some of this information. On this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

We appreciate you more than you know!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

They build like this in places where there is not a lot of money.

I remember seeing a lot of buildings like this in Latin and Central America.

I grew up in a panelak like you show here but we kept it clean and felt very safe. That was a long time ago and the communists never would have allowed the trash to build up like in the image I saw.

These kinds of places are everywhere there is poverty. I was shocked to see the mountain of trash.

What a bunch of bullshit this article is, trying to blame panelaks on communism. I’ve lived for 17 years in Prague; the rest of my life in both Canada and USA. In toronto, they also have panelaks: gigantic, ugly blocks of flats by the hundreds–in a western capitalist country no less! Meanwhile, in USA where I’m from they build apartment buildings from wood and sheetrock: the absolute cheapest materials to make the biggest profit. So you can hear EVERYTHING from your neighbors above you, to either side, and from below. There is NO QUESTION that the concrete and steel panelak affords more privacy and noise reduction than the shitty sheetrock and wood blocks of flats in USA.

Just fuck you for yet another “communism is evil and is to blame for everything wrong in the world” Czech bullshit article. There is nothing as droll and boring than listening to a Czech natter on about how awful it was in the old days before 1989. STFU!!!!

DM

Paneláks exist worldwide, yes — from Toronto to Berlin. No one disputes that. The difference in Czechoslovakia was that they weren’t simply one housing option among many, but a near-universal, state-driven model that reshaped how entire generations lived. That’s the historical context my article explores.

Acknowledging this doesn’t mean denying their advantages, nor does it mean “blaming communism for everything.” It means recognizing how political and social systems shape architecture and daily life. We can disagree on interpretations, but shouting “bullshit” adds nothing to the conversation. And as for telling me to “STFU”—maybe try writing something of your own before barking orders at people who actually contribute. Easy to fling insults from the comments section, harder to add anything meaningful.