Today’s Guest Post about Good King Wenceslas was written by Susan Steiner Bolhouse from Michigan. We found the accompanying illustrations and the closing video and added them.

Before delving into my chosen topic for today, I must first share with you a brief introduction as to my interest and fascination with this Christmas carol. Like the Good King, I, too, am Bohemian: my father was born and raised in Prague, and my mother ‘s family roots are all Bohemian. Bohemia is currently one of the three states which comprise the Czech Republic, and in my humble and prejudiced opinion, has the richest history and culture.

Today’s paper will not follow the title I originally submitted: Good King Wenceslas and his Descendant (Charles IV). After I started my research into this well known carol, its subject, and its author, I found more than I had expected.

Instead of adding Wenceslas’ descendent I will attempt an analysis of Wenceslas himself, as he has become known through the Christmas carol, and the story within the carol itself as told by the Anglican priest and hymn writer John Mason Neale in 1853.

John Mason Neale was centuries removed from Bohemia and the time of Wenceslas. How, you may wonder, did an English Island man become interested in a revered figure from Eastern Central Europe, some 900 years earlier? And what about the music? There is little background to the latter, but it is recognized as a Scandinavian, perhaps Finnish, springtime “carol” that with its lively tune was used to herald the festivities and beauty of spring. Lost to time is how Neale came upon it, and adapted it to his best known and enduring holiday classic.

Neale belonged to the high Anglican church, and held very true to its principles and traditions throughout his life. After his graduation from Trinity College at Cambridge University, he became a priest while still in his early 20’s. As was most reputable and honorable in his era, as in that of Wenceslas, good deeds, religious devotion, and altruism were guiding tenets. Of particular life-long interest to Neale was the unification of the Eastern Orthodox Christians (among them peoples of the Czech lands, Russia, Greece and others…) with the Anglican church. I can only assume that it was his studies of these eastern countries that introduced him to the legend – not myth – of Wenceslas.

In pursuit of these studies, Neale may have come across a text by the Bohemian Chronicler , Cosmas of Prague. In 1119, he wrote:

“…but his deed I think you know better that I could tell you…no one doubts that, rising every night from his noble bed, with bare feet and only one chamberlain, he went around to God’s churches and gave alms generously to widows, orphans, those in prison and afflicted by every difficulty, so much so that he was considered not a prince, but the father of all the wretched.”

Neale, of course, took some liberties while writing this musical narrative, yet held very true to particular details which reflect the bohemian character and pride.

Let me set the stage and introduce you to the first verse:

Good King Wenceslas looked out

on the feast of Stephen,

When the snow lay round about,

deep and crisp and even.

Brightly shone the moon that night,

though the frost was cruel

When a poor man came in sight

gathering winter fuel.

At the time this Christmas story is set, Wenceslas was not a king, but rather a duke. He was born in 907, in Prague, to Vratislav I, the duke of Bohemia, and Drahomira, his wife, the daughter of a pagan tribal chief. Paganism was still widely practiced in Bohemia, even as Christianity – particularly Catholicism – became the religion of the people. At their marriage, it is said that Drahomira’s wedding gift to Vratislav was her conversion to Christianity.

The education and upbringing of their first child, Wenceslas, was given over to his paternal grandmother, Ludmila who was known for her religious devotion and kindness. Through her instructions, she influenced him in the ways of Christianity, piety, and self-sacrifice. Some years later, she also took Boleslav, Wenceslav’s younger brother, under her tutelage.

Wencelas’ father died in 921, leaving his title and lands to his 13 year old son; Ludmila, the young duke’s grandmother, became regent (but tragically, not for long).

During Ludmila’s years of educating Wenceslas and Boleslav, their mother Drahomira had became increasing jealous of her mother-in-law’s influence on her sons, the eldest in particular. The fact that many of the teachings were centered on Christianity only heightened the animosity felt by the younger woman towards her elder.

Ludmila’s regency was short-lived: she was murdered just months after her own son’s death by command of Drahomira. Now installed as regent, Drahomira immediately reverted back to her pagan roots and customs, and took severe action against Bohemian Christians, brutalizing and taxing the Bohemian subjects. Fortunately, this evil rule lasted less than five years until her son aged into majority, and became the Duke of Bohemia in his own right.

Among his first acts in 925 was to exile his mother from the Bohemian lands for life, and to restore Christianity and the government to his people.

Wenceslas wanted to do right by his subjects – and his brother – in particular. He understood the nature of resentment that the latter harbored against him for being the heir to all their fathers lands and titles. To keep good family peace, he selflessly divided his land inheritance with Boleslav, giving him the larger territory.

The young duke took his grandmother’s exemplary teachings, grace and generosity towards others, to heart. Just four short years after her death, with the urging of her grandson, and support from the church, Ludmila was canonized, being cited for her kindnesses and charity. To this day she is considered the patron saint of Bohemia, converts, the Czech Republic, problems with in-laws, and widows.

At last, Duke Wenceslas was free to rule over Bohemia as he saw God had given him the right. During his too short reign he introduced an education system which permitted non-nobility and non-clerics to read and write, a structure for law and order, a government that was not punitive and excessively taxing, and was deeply revered for his good deeds towards the poor and needy, and his heart-felt piety.

The second line reference to the feast of Stephen, is to St. Stephen’s day, December 26, the first of the twelve days of Christmas. St. Stephen, considered to be the first Christian martyr, is venerated by believers and communities who in his name, do acts of charity for the poor, and those less fortunate. This date is known as Boxing Day in England, and is considered as important a holiday as December 25. Perhaps John Mason Neale chose it specifically for its tradition of giving money to the poor. This is what Wenceslas was committed to, on this frosty, snowy, crisp night.

The second verse is:

Hither, page, and stand by me

If thou knowest telling:

Yonder peasant, who is he,

Where and what his dwelling?

Sire, he lives a good league hence,

Underneath the mountain,

Right against the forest fence

By St. Agnes fountain

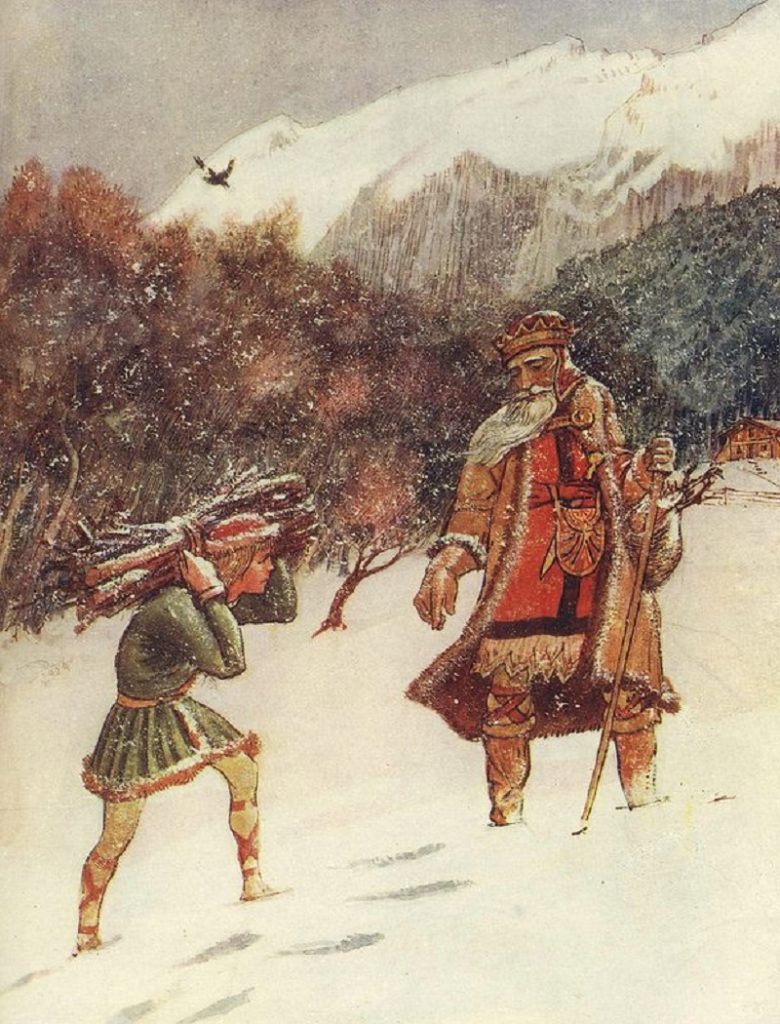

In my mind’s eye, I can imagine Wenceslas looking out from his castle window draped in warm garments, when he notices the peasant. Answering his opening question, the page indicates that he is familiar with this man who is quite far, a league – or +/- three miles, from his home.

Bohemia has many mountain ranges; throughout its history forestry has been a strong industry for building needs and survival. That there is a fence up against the forest line makes the reader believe that this certain wooded parcel was being protected from outsiders.

And, ah, yes, there is a St. Agnes of Bohemia (and several fountains in her honor). Here the author takes some poetic license: St. Agnes wasn’t born until three centuries after Wenceslas. She is often referred to as the “princess-nun”: she was born the daughter of Ottocar I, the king of Bohemia. After two royally arranged betrothals which did not lead to the altar for lack of political gain, she had enough of being used as a matrimonial pawn, and determined to live a purposeful life dedicated to the observance of poverty, aiding the sick, and spiritual works. In Prague she established the hospital of St. Francis, two priories, and two monastic orders. She was elevated to sainthood for her visions and healing.

The next verses are self-explanatory:

Bring me flesh, and bring me wine

Bring me pine logs hither

Thou and I will see him dine

When we bring them thither.

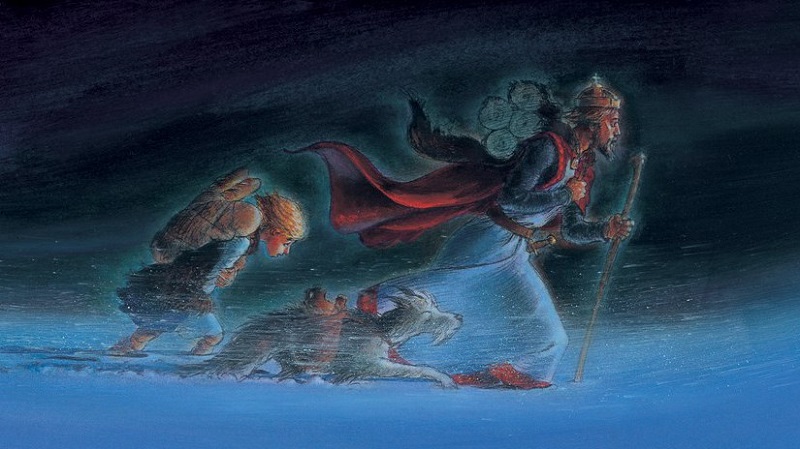

Page and monarch, forth they went

Forth they went together

Through the rude wind’s wild lament

And the bitter weather.

The fifth verse begins with the page’s gentle complaint to his duke:

Sire, the night is darker now,

And the wind blows stronger.

Fails my heart, I know not how,

I can go no longer.

To which his sire responds, without anger or impatience

Mark my footsteps my good page

Tread thou in them boldly;

Thou shalt find the winter’s rage

Freeze thy blood less coldly.

Wenceslas is leading the way through this bitter weather, the night after the festivities of Christmas, to share bounty, comfort and charity with the unknown peasant.

Author John Mason Neale pulls his story together in the last verse. In the final eight lines he is able to not only show the Duke’s good spirit, but also provides a peek into his power of goodness, allowing the snow to melt under his steps, and to warm the earth.

In his master’s steps he trod

Where the snow lay dented.

Heat was in the very sod

Which the saint had printed.

Neale’s four closing lines can be interpreted as the summation of a sermon he may have preached:

Therefore, Christian men, be sure

Wealth or rank possessing;

Ye who now will bless the poor

Shall yourselves find blessing.

Despite being a Christian hymn, its message of charitable giving, generosity to others, succor to those less fortunate is universal, to all religions and beliefs.

Before the analysis of the Good King Wenceslas carol, I introduced you to his background, parents, and grandmother. It is appropriate to now do a brief summary of his short life.

Wenceslas, also known as Vaclav the Good, was above all, a most devout Christian and friend of the church. His short reign was marked by his generous welcome of German missionaries who had been viewed with suspicion and bad intentions while his mother Dragomira was regent, and his fervent impulse to build churches in which his subjects could freely worship.( St. Vitus cathedral in Prague, a gothic architectural masterpiece, was begun under his watch. )

The middle ages were no time for extended periods of peace and contentment. In 929, King Heinrich I of Germany invaded Bohemia, in yet another power/land grab, which were common and frequent in that era. In the aftermath of this defeat, non-Christian noblemen, led by Wenceslas’ brother, Boleslav (later to be known as Boleslav the Cruel) conspired against him. On the day of September 28, 935, Boleslav lured his brother to meet with him. There was no intention of a show of brotherly love; instead, Wenceslas was assaulted and murdered by his brother’s minions as he entered a church to pray.

Today the wheels of justice move lamentably slowly, but not 1,100 years ago.

Immediately after his assassination, Wenceslas was considered a martyr, and venerated as a saint, and is the patron Saint of the Czech Republic.

Posthumously, to confer the absolute highest order of respect and admiration , the Holy Roman Emperor Otto bestowed upon him the title of King.

In as much as the stories of Wenceslas were woven from truth and legend, in the mid 1400’s Pope Pius II officially declared the legend of Wenceslas to be indeed, fact.

Should you be fortunate enough to visit the Czech Republic, Prague in particular, you will see King Wenceslas – Vaclav the Good – honorably depicted in statues on the Charles Bridge, dominating Wenceslas Square, in stained glass windows in the St. Vitus cathedral…everywhere!

And you will be familiar with this beloved man who lived a life of worth, which elevated him to both a king and a saint.

Special thanks to Susan Steiner Bolhouse from Michigan for this informative post!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Become a friend and get our lovely Czech postcard pack.