One of the most mysterious political assassinations ever taken place occurred on February 15, 1933, when the Czech-born mayor of Chicago, Anton Cermák, was mortally wounded. Anton, or Tony Cermak as he was known in the United States, was the 34th Mayor of Chicago, in office from April 7, 1931 to March 6, 1933.

The traditional story is that Cermák was shot by anarchist Giuseppe Zangara, who opened fire on a crowd of people, trying to kill then President-elect Franklin Roosevelt in Bayfront Park in Miami.

Franklin D. Roosevelt accompanied Mayor Cermak in Roosevelt’s car as he was rushed to the nearest hospital.

Roosevelt was returning from a fishing trip on Feb. 15 and stopped at a rally in a Miami park. His motorcade from the harbor was greeted along the route by enthusiastic supporters cheering and waving. At the park, he found VIPs seated at a band shell and thousands more people crowded around. His open-topped car was driven up to the band shell, where the president-elect noticed Cermak.

Roosevelt smiled broadly and motioned the Chicago mayor to join him, the Tribune reported.

But Cermak shook his head and said, “After the speech, Mr. President.”

So Roosevelt took up a microphone, said a few words, then “beckoned again to Mayor Cermak, who came down the steps of the shell to the car. They shook hands warmly” and exchanged a few words.

“Suddenly two shots rang out,” the Tribune reported. One witness said Cermak fell. Another said the mayor sagged but didn’t fall down, instead turning to his friend and travel companion Ald. James Bowler and saying, “I’m hit, Jim.”

Roosevelt’s driver and security detail had immediately covered FDR and started driving away, but Bowler yelled, “Mr. Roosevelt, Mayor Cermak is shot. Wait.”

Cermak was “half dragged across the few feet” into the waiting car and pushed in next to Roosevelt.

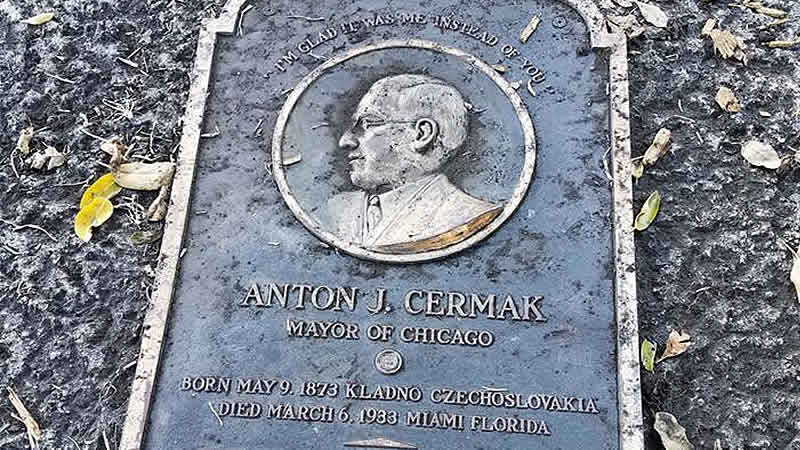

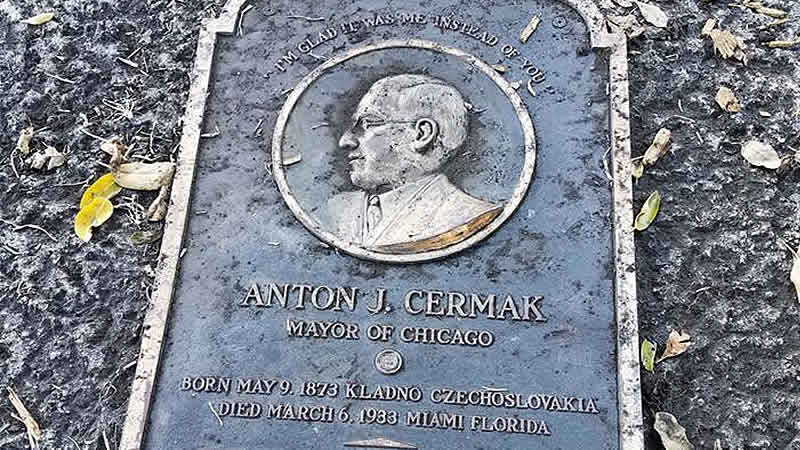

Once at the hospital, Cermak reportedly uttered the line that is engraved on his tomb. Speaking to FDR, Cermak allegedly said: “I’m glad it was me instead of you.” The Tribune reported the quote without attributing it to a witness, and most scholars doubt it was ever said.

I’m glad it was me, instead of you.

On March 4th, Roosevelt was inaugurated. He called Cermák on the telephone immediately after the ceremony.

“Tell Chicago I’ll pull through,” Cermak said from his hospital bed. “This is a tough old body of mine and a mere bullet isn’t going to pull me down. I was elected to be World’s Fair mayor and that’s what I’m going to be.”

Doctors thought the mayor would recover, but Cermak died at 5:57 a.m. Chicago time on March 6, two days after Roosevelt took the first of his four oaths of office.

The end came peacefully, the Tribune reported, with Cermak surrounded by members of his family, three daughters, their husbands and children.

The outpouring of public grief and respect in the following week was immense. Crowds met Cermak’s funeral train at stops all the way from Florida to Chicago. Back home, thousands solemnly marched through the Cermak home at 2348 S. Millard Ave. to view the mayor’s body. Then tens of thousands waited in line for hours in the bitter cold to pay their respects while his body lay in state in City Hall. Many had to be turned away then as mourners escorted his coffin to a packed Chicago Stadium for the service.

Then the final march began.

About 30,000 joined a somber procession from the stadium to Bohemian National Cemetery at Foster Avenue and Crawford Avenue (now Pulaski Road) on the Northwest Side.

A crowd of 50,000 was estimated at the cemetery. The Tribune summed it up: “Mayor Anton J. Cermak was buried yesterday after the most spectacular funeral demonstration ever seen in Chicago.”

He was buried in the Bohemian National Cemetery.

On the same day, March 10, Zangara was re-sentenced to die by electrocution for Cermak’s murder.

Five days later, the City Council voted to change the name of 22nd Street to Cermak Road.

And less than a week after that, Zangara was executed.

But there is another version of the story which says that the Al Capone mob orchestrated the plot to assassinate Cermák (not Roosevelt) because he was trying to kick out the Capone gang.

The Mobsters Theory

Zangara deliberately fired wildly over FDR’s head to distract security guards while another hit man got in close and fatally wounded the mayor. The bullets that struck Cermák came from a .45-caliber weapon whereas the gun taken from Zangara was a .38-caliber pistol.

Zangara was executed in Florida’s electric chair five weeks after the shooting. But what about the other weapon, and the other shooter?

It’s been said that Zangara allowed himself to be used as a decoy in Cermák’s murder because he was dying of cancer and wanted to provide for his family after his death. Supposedly the Capone gang cut a deal saying if Zangara would take the rap, the mob would take care of his family after his death.

Zangara insisted to the end that he wasn’t shooting at Cermák. But the rumors continued that in fact it was Cermak, and not Roosevelt, who had been the intended target.

Al Capone

Cermak’s promise to clean up Chicago’s rampant lawlessness did pose a serious threat to Al Capone and the Chicago organized crime syndicate. One of the first people to suggest the organized crime theory was reporter Walter Winchell, who also happened to be in Miami the evening of the shooting.

Both Alphonse Capone and Antonio Cermak came from families of the Old World.

Capone, the son of a barber born in Sicily, and Cermak, the son of a coal miner from Bohemia. Both men were reared on the tough streets of big cities: Capone, the Five Points of New York, Cermak, the southwest side of Chicago.

Tony Cermak

There the similarities ended, despite their common origins. Capone chose a life of crime, learning from and serving mentors that regarded all persons as expendable to their desires, while Cermak became a soul of industry and public service.

If ‘Scarface’ Al was a devil, ‘Pushcart’ Tony was certainly no angel, but assumed and affirmed an ideal that Capone would scoff at; there were solutions to problems that would not be found by a physical threat or the point of a gun.

Long-time Chicago newsman Len O’Connor offers a different view of the events surrounding Cermak’s death. He has written that aldermen “Paddy” Bauler and Charlie Weber informed him that relations between Cermak and FDR were strained because Cermak fought FDR’s nomination at the Democratic convention in Chicago, and the legend that his last words were “I’m glad it was me instead of you” was, according to O’Connor, totally fabricated by Weber and Bauler. This has been argued for years and we’ll probably never know if he said the words or not.

Finally, author Ronald Humble offered his view as to why Cermak was killed.

Did the Enforcer Order a Hit on Cermak?

In his book Frank Nitti: The True Story of Chicago’s Notorious Enforcer, Humble contends that Cermak was as corrupt as Thompson and that the Chicago Outfit hired Zangara to kill Cermak in retaliation for Cermak’s attempt to murder Frank Nitti.

Frank “The Enforcer” Nitti is arguably the most glamorized gangster in history. He was an infamous Chicago wiseguy who eventually rose to command the city’s premier underworld organization, The Outfit. Though he has been widely mentioned in fictional works, Humble’s is the first book to document Nitti’s real-life criminal career alongside his pop culture persona, with special chapters devoted to the many television shows, movies, and songs featuring Nitti. Author Ronald Humble chronicles The Enforcer’s beginnings in New York’s Navy Street Boys to his position as Al Capone’s second-in-command and eventual leadership of the outfit, with bodies piling up along the way.

Was it Nitti versus Cermak? Humble seems to believe so.

There are a lot of conflicting stories and testimonials and over the decades, there has been much speculation, misinformation, and even outright fabrications regarding the shooting of Anton Cermak. Several of the versions including statements from President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt, L.L. Lee, Miami City Manager, Chicago Alderman James Bowler, Mrs. Walter Wright, and Reporter Rex Schaeffer. You can read their statements at Chicago True Crime.

So Who Was Anton Cermák aka Pushcart Tony?

Within the infamous and muscular history of Chicago, there came a fifteen-year old kid to Chicago in 1889. A tough, immigrant kid born to a coal-miner of Bohemia in Eastern Europe that pushed a cart of refuse lumber through the Southwest side to sell as firewood. A kid that would become the Mayor of Chicago and build the first dominant political force in our country, the Chicago Democratic Party.

The story of Anton (Tony) Cermák is the story of Chicago itself.

Brought to the United States in the great immigrant wave of the 19th century, young Tony came to Chicago as an industrious teenager, seeking his own destiny. He found it in the first truly American city, Chicago, born of swamp and weed and built into a metropolis that became the heart of American labor, industry and innovation.

At first a mere laborer in the towing business, young Tony eventually took a gamble and bought the horse he was using and began to haul discarded lumber around his surrounding neighborhoods to sell as firewood. From this time of his working life comes the moniker, ‘Pushcart Tony’.

Within a few years, Cermak had employed several teams and numerous employees and did significant business. The Bohemians of the city’s southwest side were proud of him. His reputation grew, as did his ambition, and he thought seriously of improving not only his lot in life, but of those around him.

Cermak stepped in the political world at a distinctly local level. During this time, Chicago had become a heated battlefield between city Republicans and Democrats. The southwest side Bohemians, aligned with the Democrats, were at the time a party strictly run by the Irish, and only available to someone like Cermak at the lowest position.

Tony accepted a role as ‘ward heeler’ and vote-getter in the city’s 12th Ward. Quickly, he proved himself more than formidable in the job. By the success of his business, Cermak had friends, and in this new chapter of his working life, made new ones quickly. He listened and he learned, using all his personal power to convince those in his territory to support city Democrats. Soon he became a ward precinct captain, with increased stature and responsibilities. At a very early age, Tony Cermak was proving a great value to his party, and those above him took notice.

But Cermak was no scholar. The formative years of his political education were upon the streets and precincts of his part of Chicago. Canvassing his neighborhoods to getting out the ethnic vote and organizing those under his influence, he was diligent, intelligent and aggressive. When the time came for him to rise among the ranks, he set his sights on his first significant elected position in Illinois, a seat in the state council in downstate Springfield. The competition was in his own party, as young men of merit had similar ambitions. The vote for nomination was close, influenced by ethnic politics, but Cermak won by a narrow margin.

As a new Illinois General Assembyman, he was greeted in Springfield by his future colleagues: lawyers, professors, men of legislative reputation and financial means. But being less educated and sophisticated hardly slowed young Cermak down. He quickly found his own voice among the prominent men of the state council. Later in his career he stated: “I felt as though I knew people better, and had as much common sense.”

Destined to become a champion of Chicago’s ethnic classes, Tony Cermak began this great endeavor as secretary and founder of an organization called “The United Societies For Personal Liberty”.

This ambitious vessel centralized over 300 of the city’s ethnic groups and created an undeniable political force in Chicago. Originally designed to defeat new charter laws being forced on the city from Springfield and the state council (most notably the Sunday closing laws of city taverns), Cermak and the United Societies showed the power of the ethnic working (and voting) classes in America’s urban democracies, and gave Tony Cermak both political prestige and great influence in his ascending career….

The above video is from a play entitled Pushcart Tony.

It was awarded the ‘Best New Play’ of 2016 in Chicago. It’s also where the preceding paragraphs of text came from.

They have a wonderful account of Anton’s life and I highly suggest you read it!

Start with…

1) Coming to America, click here. (A new window will open.) Then read the following in order:

2) On the Make, click here. (A new window will open.)

3) The Windy City, click here. (A new window will open.)

4) Prohibition, click here. (A new window will open.)

5) Boss Cermak, click here. (A new window will open.)

6) I’m Glad it was Me, click here. (A new window will open.)

Learn more about the play at their website, Pushcart Tony.

This video below (with a horrible British computerized narration) gives a quick summary.

Here is a silent newsreel (the soundtrack burned up in a fire at the National Archives) which shows the Mayor of Chicago, Anton Cermak, enjoying sunny Florida and then lying, bandaged, in a hospital bed after the assassination. The shooter, Giuseppe Zangara, is also seen in custody.

The shooting occurred while Cermák was shaking hands with President-elect Franklin D. Roosevelt at Bayfront Park in Miami, Florida, on February 15, 1933.

Cermak was shot in the lung and seriously wounded when Zangara, who at the time was believed to have been engaged in an attempt to assassinate Roosevelt, hit Cermak instead.

At the critical moment, Lilian Cross, a doctor’s wife, hit Zangara’s arm with her purse and spoiled his aim. In addition to Cermak, Zangara hit four other people, one of whom, a woman, also died of her injuries.

Zangara told the police that he hated rich and powerful people, but not Roosevelt personally.

Gunshot Wound, Injury and Complications

Cermak died on March 6, partly because of his wounds. On March 30, however, his personal physician, Dr. Karl A. Meyer, said that Cermak’s primary cause of death was ulcerative colitis, commenting, “The mayor would have recovered from the bullet wound had it not been for the complication of colitis.” The autopsy disclosed the wound had healed, adding, “the other complications were not directly due to the bullet wound”.

In the video below you can see Cermak leaving Miami…

The following video is titles “50,000 March For Cermak In Chicago Rites” It is an impressive tribute paid to the martyred Mayor by city he loved so well. We see the funeral ceremony for Mayor Anton Cermak along with various shots of of the parade carrying the coffin. We also see the family entering the stadium where the coffin is placed in the middle of a large cross made of flowers. You can see various Senators and others at the service.

In near zero-degree temperatures, half a million people stood along the street lines to watch Cermak’s body pass to the old Chicago Stadium. Never in history of the city has there been a funeral procession so grand. The service in the stadium was non-partisan and non-religious. Tributes came from around the country.

Chicago committeeman T.J. Bowler described Cermak as the “the greatest leader the Democratic party ever had,” and World Fair President D.F. Kelly stated, “Chicago has never had a man whose passing will be felt in so many directions.”

In the end, Mayor Cermak’s legacy was felt most intimately on the streets of the city he had devoted his life to and the place he loved the most, Chicago. In this true American city, Cermak was a true American. An immigrant, a worker, and a leader. Upon his death, his city remembered him as their greatest benefactor, a champion of public service and civic pride and he is remembered as such to this day.

“I work from the same desk that Mayor Cermak sat at eighty years ago. And a day does not go by that I don’t think about Tony Cermak’s legacy and what he did for his city.” –Chicago Mayor Rahm Emmanuel

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.