My Antonia, written by Willa Cather “in memory of affections old and true”, is the story of a Czech woman who embodied the pioneer spirit. Antonia represented hard work, pride, love of land, and a desire to do what was best and right – in essence, the character of the Czech pioneers who came to this country.

Bohemia, Moravia, and Slovakia have retained identity, language, and culture throughout the centuries despite being caught in the cross-fire of major wars. The future of the people has always been dependent on the winners of the cross-fire.

Among the first settlers in the early 1600s were religious exiles from the areas now known as Czechoslovakia (Czech Republic). Augustin Herrman, who arrived in 1633, was one of the early leaders of New Amsterdam, which became New York City. Biographer Earl L.W. Heck called him “the first great American”.

The immigrant leaves behind intolerance in religion, autocratic rule, heavy burdens of government, a hard and fast class system, severe military service, and a perpetual struggle with poverty, for the United States, where fair play, a square deal, and justice are afforded to all. – Šárka B. Hrbková, Professor of Slavonic Studies, University of Nebraska

A Czech family that included master rangers of the royal forest went to Holland after 1620, and changed their family name to Philipse. Members of this family were among the early Dutch arrivals in America. They build Manor Hall at Yonkers, New York, where the family had 156,000 acres of land. At one time, Frederick Philipse’s daughter Mary and George Washington were enamored of each other. But during the American Revolution the Philipse’s supported the Tories and that was the end of their American connection. Manor Hall is owned today by the state of New York. Frederick Philipse built the old Dutch church at Tarrytown, New York.

Later immigrants included many who came because of oppression and lack of employment, or because they had a fierce desire for the freedom and opportunity that was the promise of the New World. These people were skilled in farming, and in many professions and trades.

Still later immigrants, settling in industrial cities such as Pittsburgh, worked in the steel mills, on the railroads, in the coal mines, and at many other jobs. Those who wanted found farm land in Wisconsin, Nebraska, Iowa, Kansas, the Dakotas, Oklahoma and Texas.

The first lawyer west of the Mississippi was Joseph Sosel, who in the Old Country had espoused unpopular political views. He escaped punishment when his friends smuggled him across the border in a barrel. He settled in Cedar Rapids, Iowa.

The immigrants were of robust body and spirit. To survive their three-month voyage across the ocean in overcrowded, unventilated, unsanitary, and inflammable quarters, the pioneers had to have strength of body and mind. Many died of starvation, suffocation, or disease on these voyages. Some immigrants formed themselves into groups, and appointed watchmen who took turns protecting the passenger’s lives and precious-but-scant property from ignorant, barely skilled, or drunken seamen who were captain and crew.

Not until 1855 were immigrants guaranteed a permanent immigrant depot where they were protected from thieves and were given assistance, in exchange for money, for purchasing tickets to their final destinations. Not until then were they given a decent and honest reception to these shores.

These pioneers had vision.

They had dreams.

And they had courage.

Imagine a family from Slovakia arriving on a bitter cold day, frightened and homesick, amid throngs of people who did not speak their language and in an atmosphere of red skies, black soot and smoke. Imagine the family seeking to homestead in Nebraska, coming from a land of rolling hills and trees and finding the flat prairies, where were uteerly devoid of trees until man began to plant them.

In Willa Cather’s My Antonia, when Jim Burden saw Antonia in middle age, life had been rough on her. Her weathered face told of the hard work she had encountered on the Nebraska prairie. But Jim Burden loved her still for what was within her. Her magnetism was warm, lively soul were still brightly alive.

“These were the real sources of my love for her,” Jim said.

For the pioneers 300 years ago or today, advancing age does not diminish character.

In the Old World, rigid classes divided the people. In the New World, the baby born in a log cabin could one day become President, illustrating a social flexibility that united the people and made them as one. A “new aristocracy”, for want of a better term, was created. It is composed of people with strong talents and strong intellects, who understand that the “cultivated person” knows who he is, is comfortable with that knowledge, and for that reason is at ease with others like himself. That person’s major roles may involve food preparation, or religious rituals, or care of the young or old, or classical learning, or exploration of old beliefs and old arts, or a career in a profession or business, or whatever. It is all a creation of the freedom that still beckons to these shores many who are certain there must be a better way, and are confident they will find it here. When they find it, their appreciation of their new land cannot be matched among those who have no personal memory of how it was in other days, in other places.

So we say to the person of Czechoslovak descent, “Know your heritage.”

In the novel, Jim Burden described Antonia as not only a person, but also a symbol of courage, hope, and that elusive quality of being able to see the good in so many things.

“It is no wonder that her sons stood tall and straight,” he said. “She was like a rich mine of life, like the founders of early races.”

It is no wonder that those who inherit the richness of the Czechoslovak culture stand tall and straight, for their culture is, like Antonia’s, a rich mine of life.

– – –

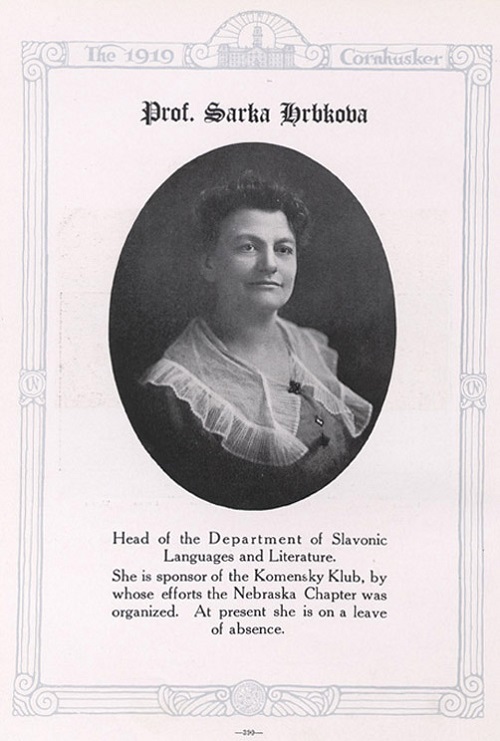

The above was written by Šárka B. Hrbková, the Chair of Slavonic Studies at the University of Nebraska Lincoln 1908-1919, in an address held July 4, 1917 in Krug Park Omaha discussing a book which we produce in hardcover, My Antonia.

We do recommend that if you order the book, that you get the hard cover copy, as that is the Distinct Press edition and royalties help to support and fund this website. You can order by clicking on the image below or on this link.

Yes, that is one of the Tres Bohemes, Zynnia, on the book cover. ;)

Šárka B. Hrbková (1878 – 1948) was the sister of the first chairman Jeffery D. Hrbek. She took the place of her brother after his sudden death during his first semester at the University in 1907. The program was not off to a good start with the long struggle to establish it followed by the demise of its first instructor in. Like her brother she too hailed from Cedar Rapids Iowa and also attended the State University of Iowa. There she earned her B.A. in 1909. Previously she taught in the public schools of Cedar Rapids from 1895-1906 as well as organizing the first night school for foreigners in the region. During the summer of 1908 the University of Nebraska contacted her about filling the position previously occupied by her brother. She began teaching in the fall of the 1908.

Šárka Hrbková was with the University from 1908-1919. In this era Czech was referred to as Bohemian and was eventually taught alongside Russian in the Slavonic Department. Under Hrbková’s chairmanship, the Slavonic program grew from eight courses in 1907 to twenty by 1919. In addition to her role as a professor during World War I she was appointed to chair the Women’s Committee of the Nebraska State Council of Defense from 1918-1919. Her career at the University came to an end following a health related leave of absence in Los Angles California. During this leave of absence the Board of Regents at the University decided to discontinue the Czech program. The Board maintained low enrollment was the impetus for this decision.

I should be ashamed if I could not speak to my mother in the language in which she first spoke to me, but I should be equally ashamed, if my mother had not seen to it that I received an education in English, the language of my country. – Šárka B. Hrbková

Hrbková went on to challenge the Board of regents allegations that the Slavic program was under utilized by students while she remained in California. Her involvement in the Nebraska State Council of Defense during World War I may have been the issue causing this abrupt change in the administrations attitude toward the program. In a letter written to Chancellor Samuel Avery she links her involvement in the Council of Defense and the 1918 loyalty trials of University staff members to the discontinuation of the program. The war may have been over but the wounds of the University had not healed.

In the image above, we see Šárka B. Hrbkova from 1919, the year she was dismissed from the University and the Slavonic Department was discontinued.

Šárka ultimately left her position at the University. She took a position in New York City as the manager of the Czechoslovak Bureau of the Foreign Language Information Service. During her lifetime she published numerous translations of Czech literature as well as writing about immigration, Americanization and Czech-American and Czech history. She was the first woman to chair what is now the Czech Language program.

In 1976, Věra Stromšíková-Petráčková became the second woman to chair the program, followed by Dr. Míla Šašková-Pierce in 1989.

Biographical Source: Nebraska University

Purchase My Antonia today.

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Become a friend and get our lovely Czech postcard pack.