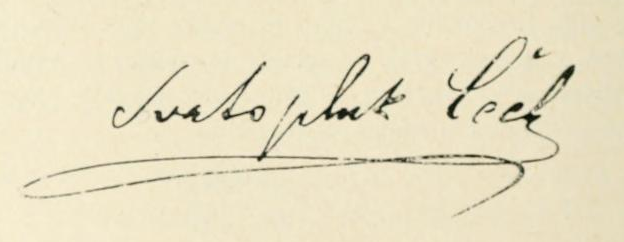

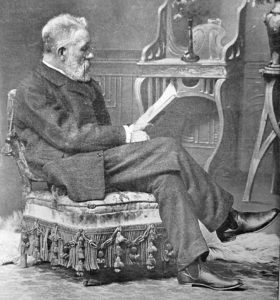

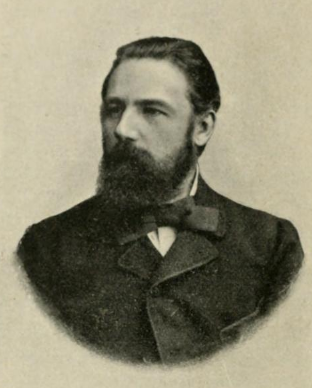

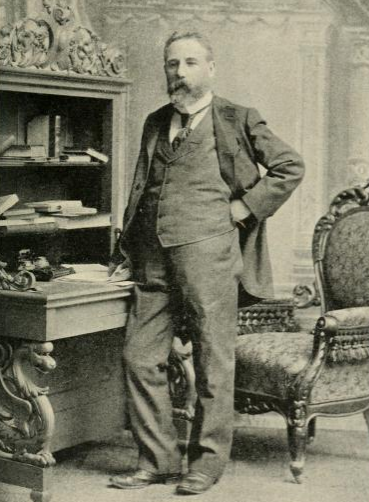

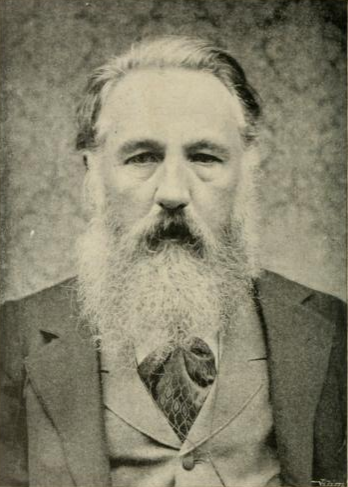

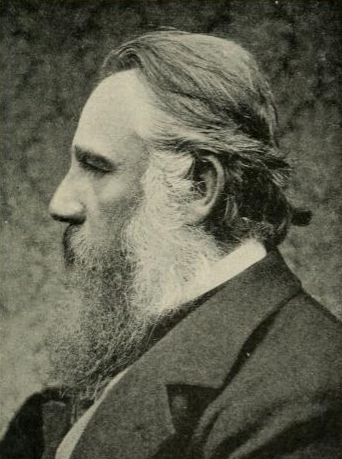

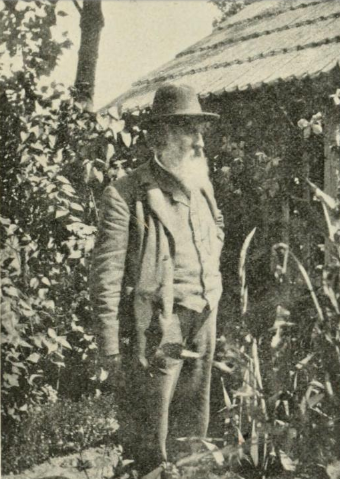

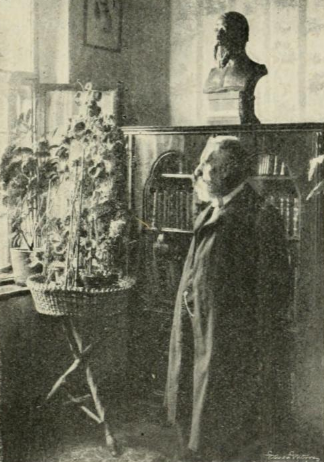

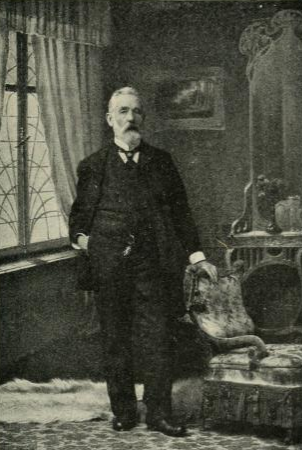

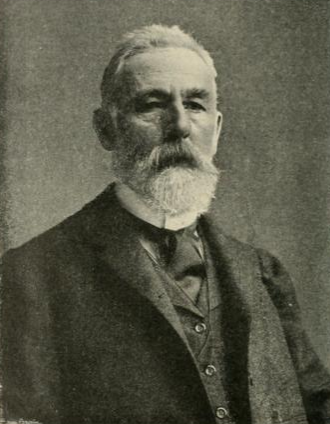

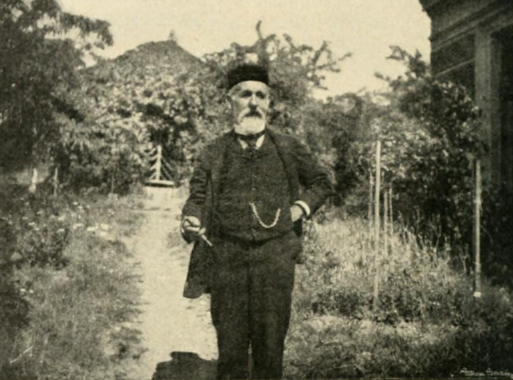

Today I am sharing a reprint from an old book, published in 1920. It’s a translation from a Czech story, Foltyn’s Drum written by Svatopluk Čech. The rare images throughout the bulk of the story are of Svatopluk Čech from a book published in 1908 entitled, O Svatopluku Čechovi.

Svatopluk Čech

Čech was born on February 21, 1846, in Ostředek near Benešov. He died February 23, 1908, Prague. Svatopluk Čech was the son of a government official, and thus spent his youth in various parts of his native land, attending schools in Postupice, Liten, Vrány, Litoměřice and Prague, securing his degree in the Piaristic Gymnasium in 1865.

Čech was born on February 21, 1846, in Ostředek near Benešov. He died February 23, 1908, Prague. Svatopluk Čech was the son of a government official, and thus spent his youth in various parts of his native land, attending schools in Postupice, Liten, Vrány, Litoměřice and Prague, securing his degree in the Piaristic Gymnasium in 1865.

Later, he studied law, though as a Gymnasium student he had already entered the field of literary effort, using the pseudonym “S. Rak.” Eventually he became editor successively of several of the leading Czech literary journals. His best works appeared in the “Květy” (Blossoms), a magazine which he and his brother, Vladimir, established in 1878.

Čech traveled extensively in Moravia, Poland, the Ukraine, around the Black Sea, Constantinople, in the Caucasus, Asia Minor, Denmark, France and England. Each of these journeys bore literary fruit.

While Čech is unquestionably the greatest epic poet of the Czechoslovaks and by some critics is ranked as the leading modern epic poet of Europe, some of his shorter prose writings are also notable as examples of enduring literature.

Čech ‘s title to superlative distinction in the field of poetry is earned through the following works which discuss broad humanitarian, religious and political questions with democratic solutions in each case.

Čech ‘s title to superlative distinction in the field of poetry is earned through the following works which discuss broad humanitarian, religious and political questions with democratic solutions in each case.

“Adamite” (The Adamites) is an epic of the Reformation describing the rise and fall of this peculiar religious sect.

“Bouře” (Tempests) and “Sny” (Dreams) are in the Byronic manner.

“Čerkes” is a picture of the life of a Czech immigrant in the Caucasus.

“Evropa” (Europe) studies the forces disintegrating ancient Europe.

“Ve Stínu Lípu” (In the Shade of the Linden Tree) depicts with rich touches of delicate humor such types as the simple peasant, the upstart tailor-politician, the portly miller, the one-legged soldier and others, each relating experiences of his youth, a veritable Czech “Canterbury Tales.”

In “Václav z Michalovic” he presents a sorrowful epic of the gray days after the Battle of White Mountain.

“Slavie” is a truly Utopian picture of Panslavism.

“Dagmar” unites the threads binding Czech with Danish history.

“Lešetinský Kovář” (The Blacksmith of Lešetin), a distinctively nationalistic poem, dramatically portrays the struggles of the Czechs against the insidious methods of Germanization. This poem was suppressed in 1883 and not released until 1899, being again prohibited after August, 1914, by the Austrian government. Portions of this vividly genuine picture have been translated into English by Jeffrey D. Hrbek.

“Petrklíče” and “Hanuman” are collections of lovely fairy tales and plays in Cecil’s most delightful verse.

“Modlitby k Neznámému” (Prayers to the Unknown) is a series of meditations in pantheistic vein on the mysteries of the universe.

“Zpěvník Jana Buriana” (The Song Book of Jan Burian) solves monarchists tendency with the one true answer — democracy.

“Písně Otroka” (Songs of a Slave), of which some fifty editions have been published, not only in Bohemia, but in the United States as well, represent, through the symbolism of oriental slavery, the modern bondmen who are in mental, moral, political and industrial subjection.

Of his larger prose works, the novels “Kandidát Nesmrtelnosti” (A Candidate for Immortality) and “Ikaros” are best known, but humor and satire, together with genuine story-telling ability, hold the reader far more tensely in his delicious “Výlet Páně Broučkův do Měsíce” (Mr. Broueek’s Trip to the Moon) and in his ten or twelve collections of short stories, arabesques and travel sketches.

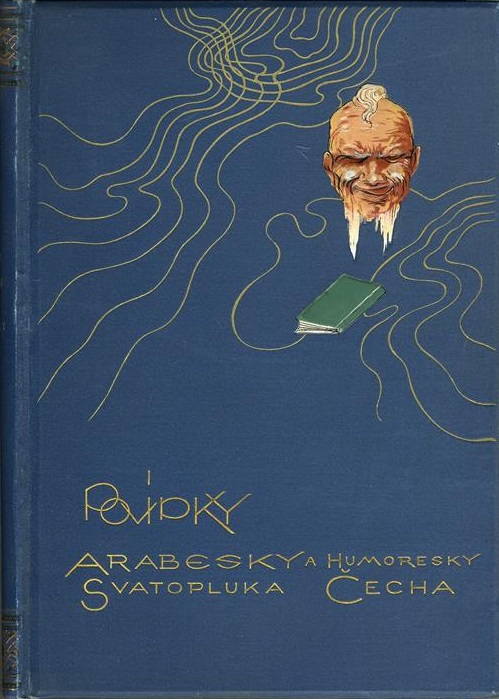

The story I am sharing today, “Foltyn’s Drum” is selected from Čech’s “Povídky, arabesky a humoresky. IV” (Fourth Book of Stories and Arabesques).

Foltyn’s Drum

Old Foltýn hung on his shoulder his huge drum, venerable relic of glorious patriarchal ages, and went out in front of the castle. It seemed as if indulgent time had spared the drummer for the sake of the drum. The tall, bony figure of Foltýn — standing in erect perpendicularity in soldier fashion, wrapped in a sort of uhlan cape, with a face folded in numberless furrows, in which, however, traces of fresh color and bright blue eyes preserved a youthful appearance, with a bristly gray beard and gray stubble on his double chin, a broad scar on his forehead, and a dignified uniformity in every motion — was the living remnant of the former splendor of the nobility.

Old Foltýn was the gate-keeper at the castle, an honor which was an inheritance in the Foltýn family. As in the Middle Ages, vassal families devoted themselves exclusively to the service of their ruler, so the Foltýn family for many generations had limited its ambitions to the rank of gate-keepers, stewards, granary-masters, herdsmen and game- wardens in the service of the noble proprietors of the castle. Indeed one member of the family had become a footman for one of the former masters and thereby the boast and proud memory of his numerous kinsmen.

Old Foltýn was the gate-keeper at the castle, an honor which was an inheritance in the Foltýn family. As in the Middle Ages, vassal families devoted themselves exclusively to the service of their ruler, so the Foltýn family for many generations had limited its ambitions to the rank of gate-keepers, stewards, granary-masters, herdsmen and game- wardens in the service of the noble proprietors of the castle. Indeed one member of the family had become a footman for one of the former masters and thereby the boast and proud memory of his numerous kinsmen.

Well then, old Foltýn stepped forth with his drum before the castle, to all appearances as if he wished to drum forth the mayor and the councilmen to some exceedingly important official duty, but in truth, alas, to noisefully assemble an army of old women to their work on the noble domain.

He slightly inclined his head and swung the sticks over the ancient drum. But what was that? After several promising beginnings he suddenly concluded his performance by a faint tap. I am convinced that many an old woman, hearing that single indistinct sound, dropped her spoon in amazement and pricked up her ears. When that mysterious sound was followed by no other she doubtless threw a shawl over her gray braids and running to the cottage across the way, met its occupant and read on her lips the same question her own were forming: “What happened to old Foltýn that he finished his afternoon artistic performance with such an unheard of turn?”

It happened thus: If you had stood in Foityn’s place at the stated moment and if you had had his falcon eyes you would have descried beyond the wood at the turn of the wagon-road some sort of dark object which with magic swiftness approached the village. Later you would have distinguished a pair of horses and a carriage of a type never before seen in those regions.

It happened thus: If you had stood in Foityn’s place at the stated moment and if you had had his falcon eyes you would have descried beyond the wood at the turn of the wagon-road some sort of dark object which with magic swiftness approached the village. Later you would have distinguished a pair of horses and a carriage of a type never before seen in those regions.

When the gate-keeper had arrived at this result of his observation, he recovered suddenly from the absolute petrifaction into which he had been bewitched by the appearance of the object and raced as fast as his legs would allow back to the castle.

Beruška, the steward’s assistant, was just bidding a painful farewell to a beautiful cut of the roast over which the fork of his chief was ominously hovering when Foltýn with his drum burst into the room without even rapping. He presented a remarkable appearance. He was as white as chalk, his eyes were staring blankly, on his forehead were beads of sweat, while he moved his lips dumbly and waved his drumstick in the air. With astonishment all turned from the table toward him and were terrified in advance at the news whose dreadful import was clearly manifested in the features of the old man.

“The nob — nobility!” he stuttered after a while.

“The nob — nobility!” he stuttered after a while.

“Wh — what?” burst forth the steward, dropping his fork on the plate.

“The nobility — beyond the wood — ” answered Foltýn with terrible earnestness.

The steward leaped from his place at the table, seized his Sunday coat and began, in his confusion, to draw it on over his striped dressing-gown. His wife, for some unaccountable reason, began to collect the silver from the table. Miss Melanie swished as she fled across the room. Beruška alone stood unmoved, looking with quiet satisfaction at his chief, whom Nemesis had suddenly overtaken at his customary culling of the choicest pieces of the roast.

In order to interpret these events I must explain that our castle, possibly for its distance and lack of conveniences, was very little in favor with its proprietors. From the period of the now deceased old master, who sojourned here a short time before his death, it had not beheld a single member of the noble family within its weather-beaten walls. The rooms on the first floor, reserved for the nobility, were filled with superfluous luxury. The spiders, their only occupants, let themselves down on fine threads from the glitteringly colored ceilings to the soft carpets and wove their delicate webs around the ornamentally carved arms of chairs, upholstered in velvet.

The officials and servants in the castle knew their masters only by hearsay. They painted them as they could, with ideal colors, to be sure. From letters, from various rumors carried from one manor to the next, from imagination, they put together pictures of all these personages who, from a distance, like gods, with invisible hands reached out and controlled their destinies. In clear outlines there appeared the images of barons, baronesses, the young baronets and sisters, the maids, nurses, the wrinkled, bewigged proctor, the English governess with a sharp nose, the fat footman, and the peculiarities of each were known to them to the minutest detail. But to behold these constant objects of their dreams and discussions, these ideals of theirs, face to face, was for them a prospect at once blinding and terrifying.

The officials and servants in the castle knew their masters only by hearsay. They painted them as they could, with ideal colors, to be sure. From letters, from various rumors carried from one manor to the next, from imagination, they put together pictures of all these personages who, from a distance, like gods, with invisible hands reached out and controlled their destinies. In clear outlines there appeared the images of barons, baronesses, the young baronets and sisters, the maids, nurses, the wrinkled, bewigged proctor, the English governess with a sharp nose, the fat footman, and the peculiarities of each were known to them to the minutest detail. But to behold these constant objects of their dreams and discussions, these ideals of theirs, face to face, was for them a prospect at once blinding and terrifying.

In the castle, feverish excitement reigned. From the upper rooms echoed the creaking of folding-doors, the noise of furniture being pushed hither and thither, the whisking of brooms and brushes. The steward’s wife ran about the courtyard from the chicken house to the stables without a definite purpose. The steward hunted up various keys and day-books and charged the blame for all the disorder on the head of Beruška, who, suspecting nothing, was just then in the office, rubbing perfumed oil on his blond hair.

Old Foltýn stood erect in the driveway with his drum swung from his shoulder, every muscle in his face twitching violently as he extended his hand with the drumstick in the direction of the approaching carriage as if, like Joshua of old, he execrated it, commanding it to tarry in the village until all was in readiness. Through his old brain there flashed visions of splendidly ornamented portals, maids of honor, schoolboys, an address of welcome, flowers on the pathway. . . . But the carriage did not pause. With the speed of the wind it approached the castle. One could already see on the road from the village the handsome bays with flowing, bright manes and the liveried coachman glittering on the box. A blue-gray cloud of dust arose above the carriage and enveloped a group of gaping children along the wayside. Hardly had Foltýn stepped aside a little and doffed his shaggy cap, hardly had the soft white silhouette of Melanie disappeared in the ground-floor window, when the eminent visitors rattled into the driveway.

Old Foltýn stood erect in the driveway with his drum swung from his shoulder, every muscle in his face twitching violently as he extended his hand with the drumstick in the direction of the approaching carriage as if, like Joshua of old, he execrated it, commanding it to tarry in the village until all was in readiness. Through his old brain there flashed visions of splendidly ornamented portals, maids of honor, schoolboys, an address of welcome, flowers on the pathway. . . . But the carriage did not pause. With the speed of the wind it approached the castle. One could already see on the road from the village the handsome bays with flowing, bright manes and the liveried coachman glittering on the box. A blue-gray cloud of dust arose above the carriage and enveloped a group of gaping children along the wayside. Hardly had Foltýn stepped aside a little and doffed his shaggy cap, hardly had the soft white silhouette of Melanie disappeared in the ground-floor window, when the eminent visitors rattled into the driveway.

In the carriage sat a gentleman and a lady. He was of middle age, wore elegant black clothes and had a smooth, oval, white face with deep shadows around the eyes. He appeared fatigued and sleepy, and yawned at times. The lady was young, a fresh-looking brunette with a fiery, active glance. She was dressed in light colors and with a sort of humorous, coquettish smile she gazed all around.

When they entered the driveway, where practically all the occupants of the castle welcomed them with respectful curtsies, the dark gentleman fixed his weary, drowsy eyes on old Foltýn who stood in the foreground with loosely hanging moustaches, with endless devotion in his honest blue eyes, and with an expression of contrite grief in his wrinkled face, his patriarchal drum at his hip.

When they entered the driveway, where practically all the occupants of the castle welcomed them with respectful curtsies, the dark gentleman fixed his weary, drowsy eyes on old Foltýn who stood in the foreground with loosely hanging moustaches, with endless devotion in his honest blue eyes, and with an expression of contrite grief in his wrinkled face, his patriarchal drum at his hip.

The baron looked intently for a while at this interesting relic of the inheritance from his ancestors, then the muscles of the languid face twitched and his lordship relieved his mood by loud, candid laughter. The bystanders looked for a moment with surprise from the baron to the gate-keeper and back again. Then they regarded it as wise to express their loyalty by blind imitation of his unmistakable example and they all laughed the best they knew how. The steward and his wife laughed somewhat constrainedly, the light-minded Beruška and the coachman with the lackey, most heartily. Even the baroness smiled slightly in the most bewitching manner.

Old Foltýn at that moment presented a picture which it is not easy to describe. He looked around several times, paled and reddened by turns, patted down his cape and gray beard in embarrassment and his gaze finally slid to the fatal drum. It seemed to him that he comprehended it all. He was crushed.

After a few condescending words to the others the nobility betook themselves to their quarters, leaving for the time being on the occupants of the lower floors the impression that they were the most handsome and the happiest couple in all the world.

After a few condescending words to the others the nobility betook themselves to their quarters, leaving for the time being on the occupants of the lower floors the impression that they were the most handsome and the happiest couple in all the world.

After a while we behold both in the general reception-room. The master rocks carelessly in the easy- chair and sketches a likeness of old Foltýn on the covers of some book. The baroness, holding in her hand a naked antique statuette, looks about the room searchingly.

“Advise me, Henry. Where shall I place it?”

“You should have left it where it was.”

“Not at all! We are inseparable. I would have been lonesome for these tender, oval, marble features.”

“But if you haul her around this way over the world she won’t last whole very long.”

“Never fear! I’ll guard her like the apple of my eye. You saw that I held the box containing her on my lap throughout the journey.”

“You might better get a pug-dog, my dear!”

The baroness flashed an angry glance at her husband. Her lips opened to make response to his offensive levity, but she thought better of it. She held the statuette carefully and swished disdainfully past the baron in the direction of a rounded niche in the wall. She was just about to deposit her charming burden when suddenly, as if stung by a serpent, she recoiled and extended a finger towards her husband. The dust of many years accumulated in the niche had left its gray trace.

The baroness flashed an angry glance at her husband. Her lips opened to make response to his offensive levity, but she thought better of it. She held the statuette carefully and swished disdainfully past the baron in the direction of a rounded niche in the wall. She was just about to deposit her charming burden when suddenly, as if stung by a serpent, she recoiled and extended a finger towards her husband. The dust of many years accumulated in the niche had left its gray trace.

“Look!” she cried.

“Look!” he repeated, pointing towards the ceiling. Prom the bouquet of fantastic flowers there hung a

long, floating cobweb on which an ugly spider was distinctly swinging.

“You wouldn’t listen to my warnings. Well, here you have an introduction to that heavenly rural idyll of which you raved.”

The baroness drew down her lips in disgust at the spider and in displeasure at her husband’s remark. Violently she rang the bell on the table. The fat footman in his purple livery appeared.

“Tell them down below to send some girl here to wipe down the dust and cobwebs,” the lovely mistress said to him with frowning brow. She sat down opposite her husband, who was smiling rather maliciously, and gazed with vexation at her beloved statuette.

A considerable time passed, but no maid appeared.

The baroness showed even greater displeasure in her countenance, while the baron smiled more maliciously than ever.

The baroness showed even greater displeasure in her countenance, while the baron smiled more maliciously than ever.

The footman’s message caused great terror below on account of the dust and the cobwebs and no less embarrassment on account of the request for a maid. After long deliberation and discussion they seized upon Foltyn’s Marianka as a drowning man grasps at a straw. After many admonitions from old Foltýn who hoped through his daughter to make up for the unfortunate drum, they drew out the resisting girl from the gate-keeper’s lodge. The steward’s wife with her own hands forced on Marianka her own yellow silk kerchief with long fringe which she folded across her bosom, placed an immense sweeping-brush in her hands, and thus arrayed the footman led his trembling victim into the master’s apartments.

The baroness had just stamped her foot angrily and approached the door when it softly opened and Marianka, pale as the wall, with downcast eye, appeared in it. The unkind greeting was checked on the baroness’ lips. The charm of the simple maid surprised her. Slender she was and supple as a reed, her features gentle and childishly rounded, the rich brown hair contrasting wonderfully with her fresh white skin, and her whole appearance breathing the enchantment of earliest springtime.

“Here, dear child!” she said to her, agreeably, pointing to the floating cobweb.

“Here, dear child!” she said to her, agreeably, pointing to the floating cobweb.

The girl bowed awkwardly, and for an instant under her light lashes there was a flash of dark blue as she stepped timidly forward. The brush did not reach the cobweb. She had to step up on her tiptoes. Her entire face flushed with a beautiful red glow, her dark-blue eye lifted itself towards the ceiling, her delicate white throat was in full outline, and below it there appeared among the fringes of the yellow shawl a string of imitation corals on the snow-white folds of her blouse. Add to this the dainty foot of a princess and acknowledge — it was an alluring picture.

When all that was objectionable had been removed, the baroness tapped Marianka graciously on the shoulder and asked, “What is your name?”

“Marie Foltýnova,” whispered the girl.

“Foltýn? Foltýn? What is your father?”

“The gate-keeper, your Grace!”

“Doubtless the man with the drum,” suggested the baron, and a light smile passed over his face.

“Go into the next room and wait for me,” said the baroness to the girl. When she had departed, the baroness turned to her husband with these words: “A charming maiden. What do you think of her?”

“Well, it’s a matter of taste.”

“I say — charming! Unusually beautiful figure, a most winsome face and withal — such modesty!”

“The statuette is threatened with a rival.”

“Jokes aside, what do you say to my training her to be a lady’s maid? To taking her into service? What do you say to it?”

“Jokes aside, what do you say to my training her to be a lady’s maid? To taking her into service? What do you say to it?”

“That your whims are, in truth, quite varied,” he answered, yawning.

The baroness indulged her whim with great energy. She immediately asked the girl if she would like to go to the city with her and, not even waiting for her answer, engaged her at once in her service, rechristened her Marietta, described in brilliant colors the position of a lady’s maid, and, at the end, made her a present of a pair of slightly worn slippers and a coquettish house cap.

Old Foltýn was fairly numbed with joyous surprise when Marianka, with the great news, returned to him. Even in his dreams he would not have thought that his daughter would be chosen by fate to become the glittering pendant to that footman of whose relationship the entire Foltýn family boasted. Instantly he forgot the incident of the drum, his gait became sturdier and his eyes glowed like a youth’s.

Several days passed. The baroness continued enthusiastic about the delights of country life and de- voted herself with great eagerness to the education of Marietta as a lady’s maid. Marietta often stood in front of the mirror wearing the coquettish cap and holding in her soft hand the large tuft of many-colored feathers which the mistress had purchased for her for brushing off the dust. Often, too, she sat on the low stool, her eyes gazing dreamily somewhere into the distance where in imagination she saw tall buildings, beautifully dressed people, and splendid equipages.

Frequently she would bury her head in her hands and lose herself in deep thought. The baron would sit idly in the easy-chair, smoking and yawning. The steward and his wife rid themselves of all fears of their eminent guests. Beruška made friends with the purple footman playing “Twenty-six” with him in the office behind closed doors when they lighted their pipes.

Frequently she would bury her head in her hands and lose herself in deep thought. The baron would sit idly in the easy-chair, smoking and yawning. The steward and his wife rid themselves of all fears of their eminent guests. Beruška made friends with the purple footman playing “Twenty-six” with him in the office behind closed doors when they lighted their pipes.

Once towards evening the baroness, with her beautifully bound “Burns,” stepped out into the flower covered arbor in the park from which place there was a distant and varied view and where she hoped to await the nightingale concert which for several evenings had echoed in the neighborhood of the castle. The baron rebuked the footman for his fatness and ordered him to begin reducing by taking a walk out into the fields. The steward and his wife were putting up fruit behind closed doors. Melanie had a toothache.

In this idyllic, peaceful moment it occurred to old Foltýn that Marianka was lingering an unusually long time in the apartments of the nobility. He disposed of the thought, but it returned soon again. The thought became every moment more and more obtrusive.

“What is she doing there so long?” he growled into his moustaches. “The mistress is not in the house.”

Involuntarily he went into the gallery and walked about a while, listening intently to sounds from above. Then he ventured on the steps, urged by an irresistible force. On tiptoes he reached the corridor of the first floor. He stole to the footman’s door and pressed the knob. It was closed. He crept to the door of the reception-room. Suddenly he paused. Within could be heard a voice — the voice of the baron. Distinctly he heard these words: “Don’t be childish! Foolish whims! The world is different from what the priests and your simple-minded parents have painted it for you. I will make you happy. Whatever you wish, you will get — beautiful clothes, jewels, money — all. I will make your father a butler, steward, maybe even something higher. You will be in the city yourself. Now, my little dove, don’t be ashamed, lift up your lovely eyes. God knows I never saw more beautiful ones!”

Involuntarily he went into the gallery and walked about a while, listening intently to sounds from above. Then he ventured on the steps, urged by an irresistible force. On tiptoes he reached the corridor of the first floor. He stole to the footman’s door and pressed the knob. It was closed. He crept to the door of the reception-room. Suddenly he paused. Within could be heard a voice — the voice of the baron. Distinctly he heard these words: “Don’t be childish! Foolish whims! The world is different from what the priests and your simple-minded parents have painted it for you. I will make you happy. Whatever you wish, you will get — beautiful clothes, jewels, money — all. I will make your father a butler, steward, maybe even something higher. You will be in the city yourself. Now, my little dove, don’t be ashamed, lift up your lovely eyes. God knows I never saw more beautiful ones!”

Foltýn stood as if thunderstruck. All the blood receded from his face. Horror and fright were depicted in it. He stooped down to the keyhole. Within he beheld the baron wholly changed. In his pale, handsome countenance there was not a single trace of sleepiness, and his dark eyes flashed with passion underneath the thin, proud brows. Uplifting by the chin Marianka’s beautiful face, flushed deep scarlet with shame, he gazed lustfully upon her heaving bosom. Her eyes were cast down, in one hand she held the statuette, in the other the tousled tuft of variegated feathers.

Foltýn put his hands up to his gray head. Anguish contracted his throat. Through his head rushed a whirl of terrible thoughts. Already he had reached for the door-knob, then quickly jerked his hand away. No! To have the baron learn that Marianka’s father had listened to his words, to stand, shamed, and apprehended in an abominable deed before his own servant — no, that must not be! All of Foltyn’s inborn loyalty rose in opposition. But what was he to do?

Foltýn put his hands up to his gray head. Anguish contracted his throat. Through his head rushed a whirl of terrible thoughts. Already he had reached for the door-knob, then quickly jerked his hand away. No! To have the baron learn that Marianka’s father had listened to his words, to stand, shamed, and apprehended in an abominable deed before his own servant — no, that must not be! All of Foltyn’s inborn loyalty rose in opposition. But what was he to do?

In the office was the footman. He would send him upstairs on some pretext. No sooner thought of than he hastened down. But the office was closed and perfect silence reigned within. Beruška and the footman who had but recently been playing cards inside were not at home. One was in the courtyard, the other out for a health promenade.

In desperation Foltýn ran down the corridor. Suddenly he paused in front of the j^il-room. He stood but a moment and then burst open the door, seized the immense drum hanging there, hung it over his shoulder and ran out into the driveway. Wildly he swung the drumsticks, bowed his head, and then a deafening rattle resounded. He beat the drum until beads of sweat stood out on his brow.

The steward, hearing the clatter, turned as pale as death. “In God’s name, Foltýn has gone mad,” he burst out. He flew to the driveway. There he beheld Beruška, holding a card hand of spades in one hand and the collar of the unsummoned drummer in the other.

The steward, hearing the clatter, turned as pale as death. “In God’s name, Foltýn has gone mad,” he burst out. He flew to the driveway. There he beheld Beruška, holding a card hand of spades in one hand and the collar of the unsummoned drummer in the other.

“Are you drunk?” shouted the clerk.

Foltýn continued obstinately to beat the drum.

From all sides figures came running in the dusk.

The steward came to Beruska’s assistance. “Stop, you maniac!” he thundered at Foltýn. “Don’t you know the baron is already sleeping? I’ll drive you out of service immediately.”

“Oh, just let him stay in service,” sounded the voice of the baron behind them. “He is a capital drummer.” Then he passed through the bowing crowd, whistling and switching his riding-boots with his whip. He was going for a walk.

When the baroness, attracted hither by the mysterious sound of the drum, had returned from the nightingales’ concert and entered the reception-room she beheld in the middle of it her beautiful, beloved statuette broken into many bits.

When the baroness, attracted hither by the mysterious sound of the drum, had returned from the nightingales’ concert and entered the reception-room she beheld in the middle of it her beautiful, beloved statuette broken into many bits.

From the weeping eyes of Marietta whom she summoned before her she at once learned the perpetrator. In great wrath she dismissed her from service on the spot. Short was the dream of tall buildings, beautiful people and splendid equipages!

At noon of the next day Foltýn stood in front of the castle and drummed the peasants to their labors. At the same time he gazed towards the forest road down which the noble carriage with marvelous speed was receding into the distance.

When the carriage disappeared in the forest Foltýn breathed a sigh of relief, dropped the drumsticks and shook his head. And then the thought came into his head that, like the drum, he no longer belonged to the present era of the world. As to the cause of the disturbance of the day before he preserved an obstinate silence unto the day of his death.

– – – – –

From the book, Czechoslovak Stories. Translated from The Original and Edited With An Introduction by Šárka B. Hrbkova, Professor of Slavonic Languages and Literatures at the University of Nebraska (1908-1919).

Published by Duffield and Company, New York 1920.

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Become a friend and get our lovely Czech postcard pack.