Do you ever wonder how a street gets its name? Unless you have an understanding of notable people throughout Czech history, you will most likely not know that several Prague streets are named after Czech world travelers. Explores, cartographers and ethnographers who made substantial contributions on the world stage.

Today we are looking at six such streets and the great people they are named after – and we sincerely hope you enjoy it as this post took over five hours to research, translate and create.

You can scroll to read the post below or watch this video we made just for you!

Don’t forget to leave us your comments in the section below the article. Enjoy!

Ulice Harantova, (Harantova Street)

Kryštof Harant (aka Kryštof Harant z Polžic a Bezdružic) was born in 1564. He was a Czech traveler, humanist, nobleman, soldier, writer and composer. He joined the Protestant Bohemian Revolt in the Lands of the Bohemian Crown against the House of Habsburg that led to Thirty Years’ War.

As a composer he represented the school of Franco-Flemish polyphony in Bohemia.

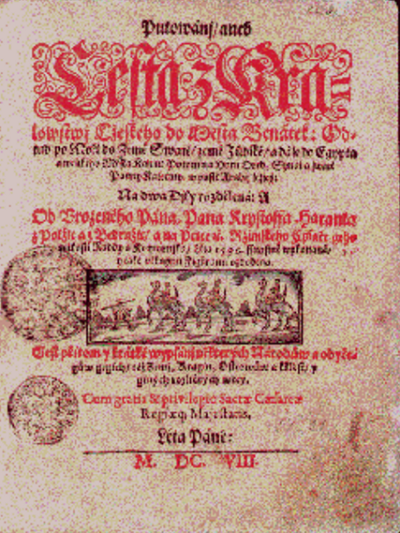

Harant is also noted for his expedition to the Middle East summarized in a travel book published in 1608 entitled,

Cesta z Království Českého do Benátek, odtud do země Svaté, země Judské a dále do Egypta, a potom na horu Oreb, Sinai a Sv. Kateřiny v Pusté Arábii (literally translated to Journey from Bohemia to Venice, from here to the Holy Land, Judea and to Egypt, later to Oreb, Sinai and St. Catherine mountain in desert Arabia).

The book is probably the first published account of the Near East by a Czech traveler. It is a comprehensive travel book with its numerous detailed illustrations, richly illustrated in the form of approximately 50 woodcuts by Harant. It describes both the travel and the details of the visited lands. As a typical example of renaissance literature it mixes entertainment with knowledge and heavily references religion.

The book gives a very detailed description of religious places and their relation to Christianity, habits of natives and natural and man-made curiosities. It stayed popular for long time and was published for the last time in year 1854. In 1638, Harant’s youngest brother, Jan Jiří, translated the text into German.

Following the victory of Catholic forces in the Battle of White Mountain, Harant was executed in the mass Old Town Square execution by the Habsburgs on June 21, 1621.

The street is in Malá Strana and leads from Maltese Square to Karmelitská Street. It was named in 1870.

Ulice Holubova (Holubova Street)

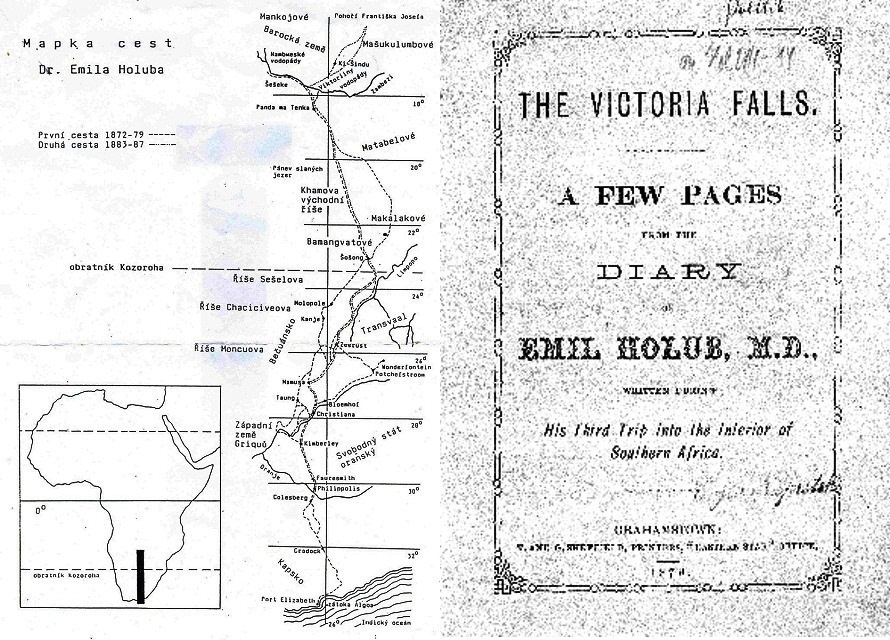

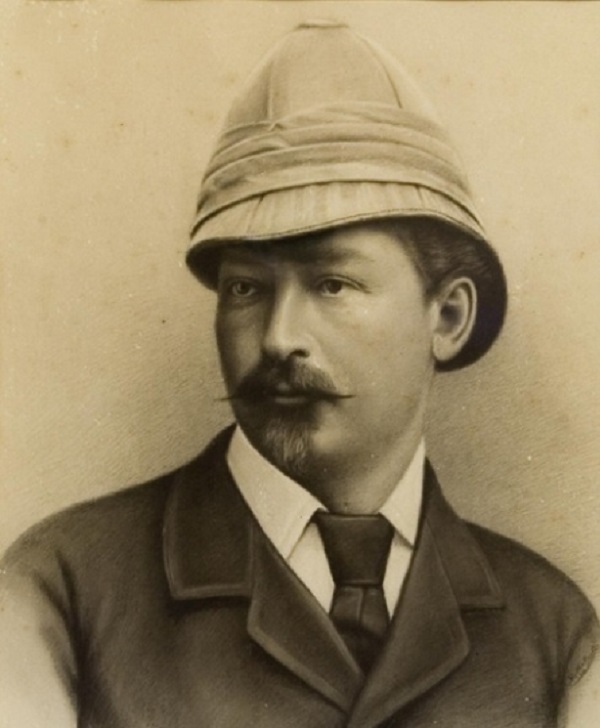

Emil Holub (October 7, 1847 – February 21, 1902) was a Czech physician, explorer, cartographer, and ethnographer. He made two expeditions to South Africa. With his wife and company, he first entered the area of dreaded Masukulum and brought extensive natural and ethnographic collections.

Inspired to visit Africa by the diaries of David Livingstone, Holub travelled to Cape Town, South Africa shortly after graduation and eventually settled near Kimberley to practice medicine. After eight months, Holub set out in a convoy of local hunters on a two-month experimental expedition, or “scientific safari”, where he began to assemble a large natural history collection.

In 1873, Holub set out on his second scientific safari, devoting his attention to the collection of ethnographic material.

On his third expedition in 1875, he ventured all the way to the Zambezi river and made the first detailed map of the region surrounding Victoria Falls. Holub also wrote and published the first book account of the Victoria Falls published in English in Grahamstown in 1879.

After returning to Prague for several years, Holub made plans for a bold African expedition. In 1883, Holub, along with his new wife and six guides, set out to do what no one had done before: explore the entire length of Africa from Cape Town all the way to Egypt. However, the expedition was troubled by illness and the uncooperative Ila tribesmen and Holub’s team was forced to turn back in 1886.

Holub mounted two highly successful exhibitions, in 1891 in Vienna, and in 1892 in Prague. Frustrated that he was unable to find a permanent home for his large collection of artifacts, he gradually sold or gave away parts of it to museums, scientific institutions and schools.

Later Holub published a series of documents, contributing to papers and magazines, and delivering lectures. Emil Holub wrote one of the most precious and least accessible books on the former Rhodesia. The original 16-page brochure that was published under the name “The Victoria Falls.” is extremely rare because he released it himself, in a stark grayish envelope, when he was in the South African city of Grahamstown in 1879. The book is only available in the Prague National Library and Náprstek Museum, one copy is also in the Library of Congress in Washington. This unique book is the only one printed at the time about the unique Victorian waterfalls.

He is also responsible for drawing the first detailed map of South Africa. You can see one such map here.

He also wrote travelogues: Sedm let v jižní Africe (Seven Years in South Africa) and Druhá cesta po Jižní Africe (The Second Journey to South Africa).

Emil Holub died in Vienna on February 21, 1902, from lingering complications of malaria and other diseases he had acquired while in Africa.

In 1952, the movie Velké dobrodružství (Great Adventure) was filmed about Holub’s expeditions. You can watch a preview of the film here.

In a 2005 poll, he was voted #90 of the 100 greatest Czechs.

The street is located in Radlice and is a continuation of Na Neklance Street and it passes on Pechláto Street. It was named in 1947.

Ulice Kořenského (Kořenského Street)

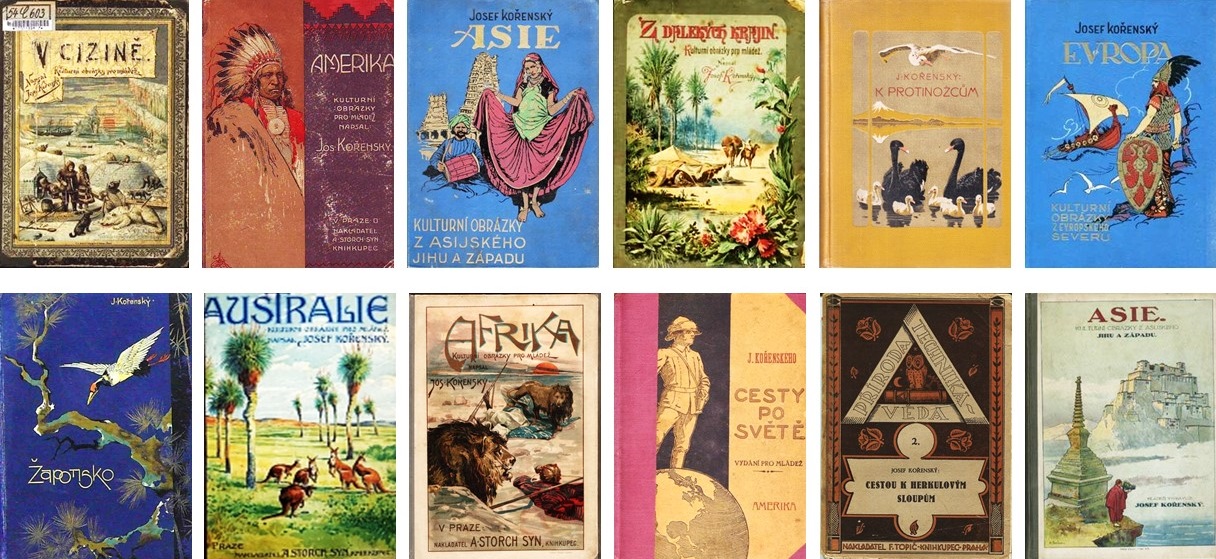

Josef Kořenský (July 26, 1847 – October 8, 1938), was a Czech traveler, educator and writer. He recorded and conveyed knowledge about the places on our planet that had been explored. He significantly contributed to the spreading of knowledge about the world in the Czech society, mainly in the first half of the 20th century. Except for Antarctica, he traveled over all the world’s continents.

He set off on each journey perfectly prepared, studying available literature and languages. He knew German, French and English, but had no difficulties with other languages, which can be proved by his translations from Norwegian. His itinerary was always clear and precise and his travels were a verification of the facts he had already known from his research.

While on the road, he carefully noted all aspects of the natural world, as well as all features of economic, cultural and religious life of the society. As a teacher, he naturally paid attention to the education of various nations, which then enriched his own teaching practice.

He believed that a teacher should travel as much as possible to be perfectly informed about the situation abroad. Children can be taught only through a genuine personal experience. He frequently published books on his travels, and most were written especially for young people, which had an obvious positive impact on the entire population.

He lived in Arbes Square, taught and directed at the school at Kořenský Street (1874-1908). He was a member of the Administrative Committee of the National Museum and a number of prestigious institutions, such as the Oriental Institute of the Czechoslovakia. The greatest tribute to his efforts in the field of science was awarded in 1927: an honorary doctorate of Natural Sciences of Charles University.

In 1920s’, he was the first traveler to be invited as a host to the Czech Radio broadcasts on a regular basis.

He died in Smíchov in 1938, at the age of 91.

The street is in Smíchov and leads from Arbes Square to Janáček’s waterfront. It was named in 1947.

Ulice Štolbova (Štolbova Street)

Josef Štolba (May 3, 1846 – May 12, 1930) was a notary, playwright, traveler and member of the Czech cultural elite.

He first began his studies at the grammar school in his native Hradec Králové, and then finished his studies in Prague. He also studied law in Prague. In 1869, he debuted as author of theatrical plays at the Prazatímní divadlo.

In 1870, he took the place of educator at the noble family of Kounic. With Count Arthur Desfours-Walderode, he made an annual trip to America in 1873. Later he traveled all over Europe and the West Indies with other noble personalities. He accompanied Josef Kořenský (who we wrote about above) to the Arctic Circle.

After returning home, he worked at the National Theater and also received a doctorate in law in 1874, serving five years in a legal practice. He was a trainee in a notary office and, in time, a notary in Nechanice, Pardubice and Královské Vinohrady. In 1880, he was involved in the Association for the Establishment of the Theater House in Pardubice.

The main subject of his writing activities were dramatic works. The dramatic work he created was mainly comedy, but he also experimented in other genres. Many of his plays are still performed today. He debuted them in the Provisional Theater and later he also performed at the National Theater.

Josef Štolba also wrote an autobiography.

Today we’re focusing on his travelogues which colorfully portray his experiences of foreign travel.

He wrote numerous travelogues about his traveling experiences, including the following:

Za oceánem (Beyond the Ocean) (1875)

Americké povídky (American Short Stories) (1883)

Na skandinávském severu (In the Scandinavian North) (1884)

Za polárním kruhem (Beyond the Polar Circle) (1890)

Prales. Obraz ze života mexických indiánů (Forest. Picture of Mexican Indians Life) (1892)

Na půdě moří urvané (On the Seas Sea) (1896)

Ze slunných koutů Evropy (From the sunny corners of Europe) (1918)

Do Západní Indie a Mexika (To West India and Mexico) (1920)

The street is in Veleslavín and starts in the street On the Edge and leads to Heyrov Square.

Ulice Vrázova (Vrázova Street)

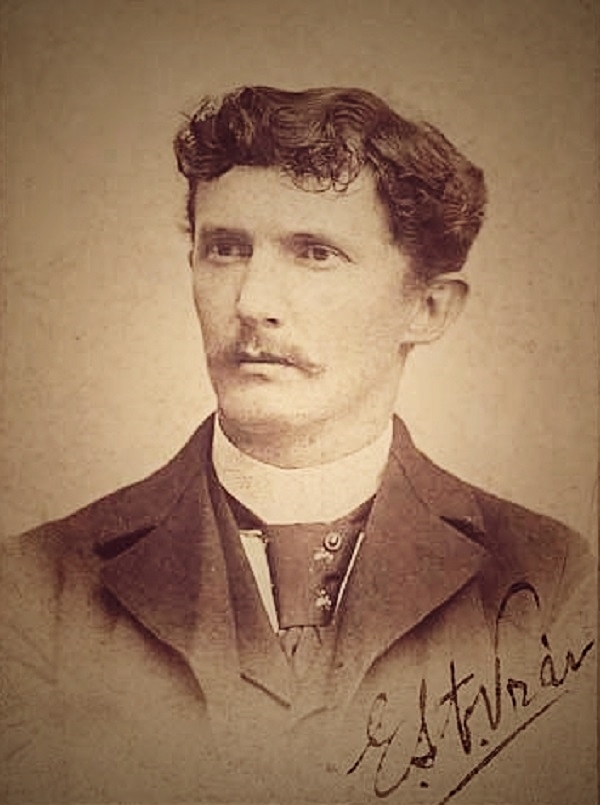

Enrique Stanko Vráz (February 8, or April 8, 1860 – February 20, 1932) was a Czech traveler and photographer, believed to be of Bulgarian origin. He has visited various parts of North, South and Central America, Asia, Africa, Borneo and New Guinea.

His true origin has always been shrouded in mystery. He claimed to have been born on either February 18 or April 8 – he changed it each time – in the year 1860 in the Bulgarian town of Veliko Tarnovo. No one has ever attemted to verify this claim. He said his father was a Russian officer or diplomat and his mother was Czech. Many historians, however, are trying to challenge Vraz’s claim.

It is speculated that he created the pseudonym Enrique Stanko Vráz because he was hiding his true identity. Those looking into this have speculated that he could be the missing poet of German origin, Karel Ilichman.

Or he could be Ferdinand Schpale of Galicia.

Or he could be Count Kolowrat.

Or he could be the illegitimate son of Prince Thurn Taxise.

Most likely, we will never know.

We do know that he was raised by the Czech patriot Bukvicka. And he was supposed to have graduated from Czech military school and started studying medicine in Switzerland, but he did not finish his studies.

We also know that he became known as a wold traveler and that during his travels, he collected a number of natural resources and works of art that he later dedicated to the National Museum.

Vraz also played an active role in the creation of independent Czechoslovakia in 1918, when he helped the future president Tomas Garrigue Masaryk and other emissaries of the Czechoslovak exile government to establish contacts with Czechoslovak ex-patriots in the United States. It is interesting that unlike other builders of the Czechoslovak state he never received any distinction. Nor was he offered a significant post.

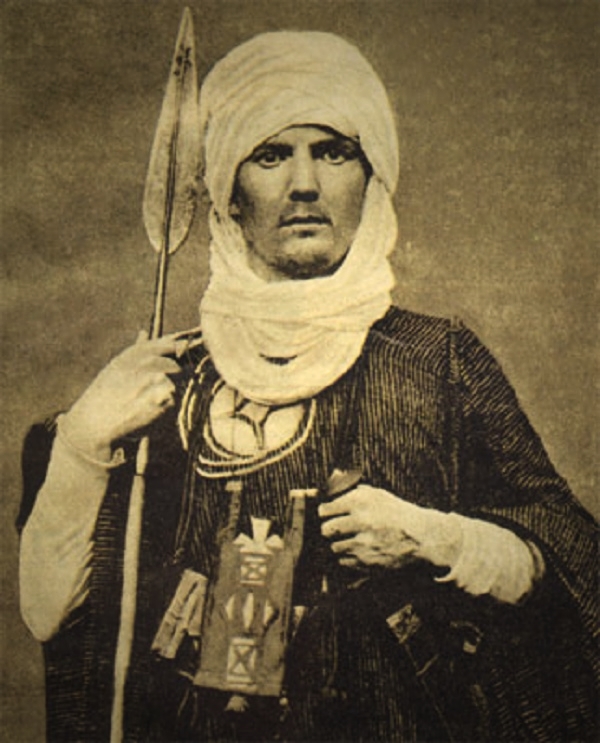

Around 1880, he moved to North Africa. In the disguise of an Arab, he tried to get out of Morocco into the Muslim town of Timbuktu. After three years of vain attempts, he decided to get to Timbuktu from the Gambia. In Gambia, however, he was overtaken by malaria, so he did not travel until 1885. When he did however, after 322 kilometers of cruising on the Gambia River, he contracted malaria again and had to go back. At the end of this year, he traveled to Liberia, Sierra Leone, and Ghana. In Ghana, he was captured by the Asans, but he was able to escape from their captivity. During his stay in West Africa, he has accumulated a vast amount of natural resources, about 15,000 insects, 1,200 birds, 600 mammals, and about 800 other items. A large part of this collection was purchased by the British Governor and expounded in Dublin. But in 1885, he donated the remaining parts of the collection to the National Museum.

From West Africa, he went to the Canary Islands where he met Polish Prince Adam Woroniecki and friend Jaroslav Bradá. At this time he decided to travel south-east from east to west. Together with Brázdou and Woroniecki, he set out on a Steamer, the Olinde Rodriguez, in July of 1889 for a trip to South America. After stopping in the Caribbean islands of Guadeloupe, Martinique and Trinidad, they landed in Venezuela (without the Prince who died after three days f contracting yellow fever). On November 23, 1892 they depart on the steamboat Bolívar ups the Orinoco River (one of the longest rivers in South America at 2,140 kilometers). Later they travel the Río Negro to Brazilian Manaus and then the Amazon River. In the middle of July, they reached the Peruvian border. After a tribute to the tribe of “skull hunters” from around the Ucayali River and after a short trip to the Rubber Gatherer, he goes to the Peruvian Andes. After overtaking several passes, he arrives in Cajamarka and arrives on the Pacific Coast on the 27th of November in 1893 at Pacasmayo. This was his journey across America. On Maipo’s Chilean Steamship, he arrives in Panama and then, after a short stop in Venezuela, arrives in Europe in 1894. In the middle of July that year he finally arrived in Prague with a lot of collections and photographs. He also brought with him forty-four birds and various mammals for the Prague Zoo. However, at that time the zoo was not yet built, so all of the animals were sold to Vienna after a short exhibition at Perstyn.

After a series of lectures in the Czech and Moravian cities, he went to North America in November of 1895. He held lectures for the Czech minority in Chicago and in New York and then left the United States in January of 1896. After 22 days of sailing, he arrived in Japan. In Tokyo and Yokohama, he purchased a number of artworks which he had sent to Prague hoping they would welcome them and he would be paid. Unfortunately, they were not interested. From Japan he headed to central China, where he sailed along the Yangtze River to Shanghai. Through Shanghai, Nanking and Hong Kong, he got to Singapore. This harbor became its starting point for a trip to Borneo where he wanted to catch orangutans. He lived among the Dajaks in the watershed of the Sadong River, Batang Luparu and Simujan for a couple of months. From Borneo, after a short stop in Singapore, he set out in October of 1896 via Moluky to New Guinea.

In December of 1896 he arrived in the territory of the Hatamu people. He got into disputes with the natives, supplies went missing, and his guides refused to continue his journey inland. Disappointed he returned to the coast. During his trip, however, he made many geographic discoveries and took away many valuable natural resources. However, most of this unique collection, which was also a great find, had to be sold to London because Prague did not have enough money to pay for the transport to Bohemia. He also brought with him two tropical fish, the first to be in Czech aquariums.

After a couple of months, he left again, this time for Venezuela, stopping briefly in Cuba before returning to Chicago where his fiancé, Vlasta Geringer, lived. He had fallen in love with her in Prague. She was the daughter of an American newspaper tycoon, a descendant of the Geringer family, and three years later (December 1897) they married. They moved to the United States, and during a journey to Mexico, they both climbed Popocatepetl volcano.

In 1899, after a series of lectures, he arrived in Arizona and New Mexico so seek out the Hopi Indians where he took a number of unique photographs.

The Boxing Rebellion in China in 1900 reawakened his interest in the country. In January of 1901, shortly after the rebellion was suppressed, he arrived in the city of Tiencina, from which he then left for Beijing. In Beijing, as one of the first Europeans, he traveled through the Forbidden City and took many photographs. After three months in China, he went to Manchuria and then to Korea, where he was the guest of the Korean prince himself. Back to Europe, he traveled from Vladivostok via Siberia and Moscow. He did not linger in Europe and did not even stop in Prague after this trip, preferring to return immediately to the United States where he now lived with his wife and his children, his son Vítězslav and his daughter Vlasta.

In the years 1903-1904, he traveled around the capital of South America, where he mainly photographed and lectured. In 1904, he visited Mexico for the second time, and together with the American archaeologist E. Thompson, he attended excavations in the Mayan city of Chichen Itza.

In 1907, he moved to Prague for a short time, but due to lack of funds, he had to return to the USA. After returning to the United States, he joined the United State ins the process of becoming a plenipotentiary of the Prague National Council to establish his American branch. He gradually became fully involved in Czech-American social life, even collaborating on the presidential campaign of President Wilson.

It was at this time that he began having trouble with his heart. On his left arm, signs of cancer were showing and the cancer resulted in an amputation in 1920.

He left the United States and took his wife and daughter to Prague on August 31, 1921 where he believed either the National or the Náprstek Museum would employ him. Neither did. Thus the only source of money came from his lectures and in minor literary royalties, so they ended up living in the workers’ quarter in Holešovice, in poverty.

Enrique Stanko Vráz often suffered from severe depressions and was treated in Professor Prusik’s Podol’s sanatorium.

On February 20, 1932, he died in Prague, at the age seventy-two years. It’s likely he was unhappy that his life-long efforts were not as appreciated as he had hoped they would be.

Sadly, in reading the above – so much of his work seemed to be in vain and other countries benefited more from his efforts, it’s no wonder he died a depressed and broken man.

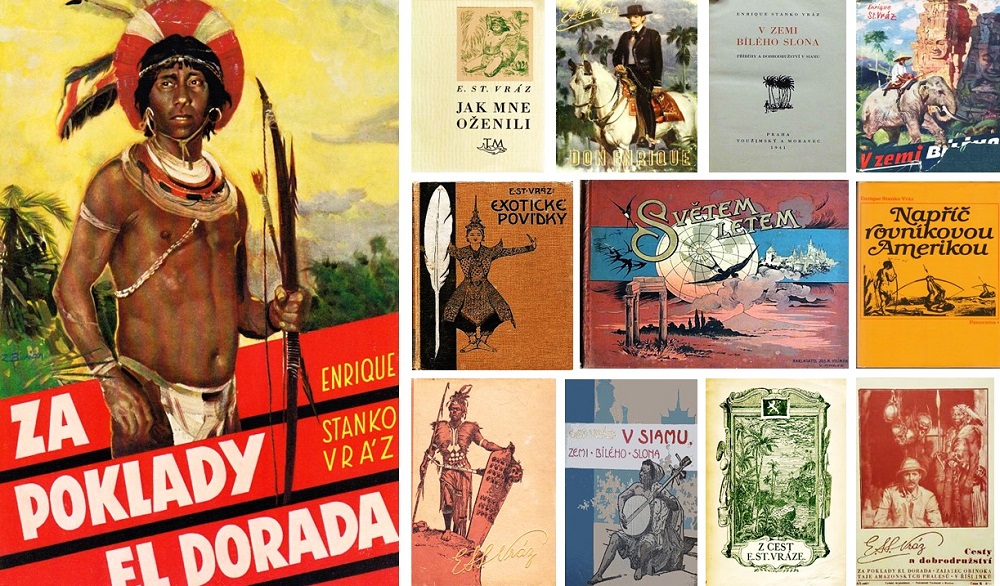

He wrote numerous travel books, here are just a few of his titles.

Z cest E. St. Vráze (From the paths E. Saint Vráze) (1898)

Napříč rovníkovou Amerikou (Across equatorial America) (1900)

V Siamu, v zemi bílého slona (In Siam, in the land of the White Elephant) (1901)

Čína (China) (1904)

Z dalekých světů (From Far Worlds) (1910)

They were richly illustrated from some of the best illustrators of the times.

“Enrique Stanko Vraz never wrote an autobiography, but his daughter, Mrs. Vlasta Vrazova did write a biography of him . It is based on diaries he used to write during his travels. The diaries, however, have not been preserved. Mrs. Vrazova lived in Czechoslovakia till the Nazi occupation in 1939 and then she moved to the United States, as she had American citizenship. She returned to Czechoslovkia after WWII as a United Nations Relief and Rehabilitation Administration representative, but as such she was a thorn in flesh of the Communist authorities when they seized power in 1948, and she was expelled from the country.”

The Communists confiscated all her property, and her father’s diaries disappeared – either during the confiscation or she herself destroyed them – no one knows.

The street is 75 meters long in Smíchov and leads from Svornosti to Staropramenné Street. It was named in 1947.

Ulice Budovcova (Budovcova Street)

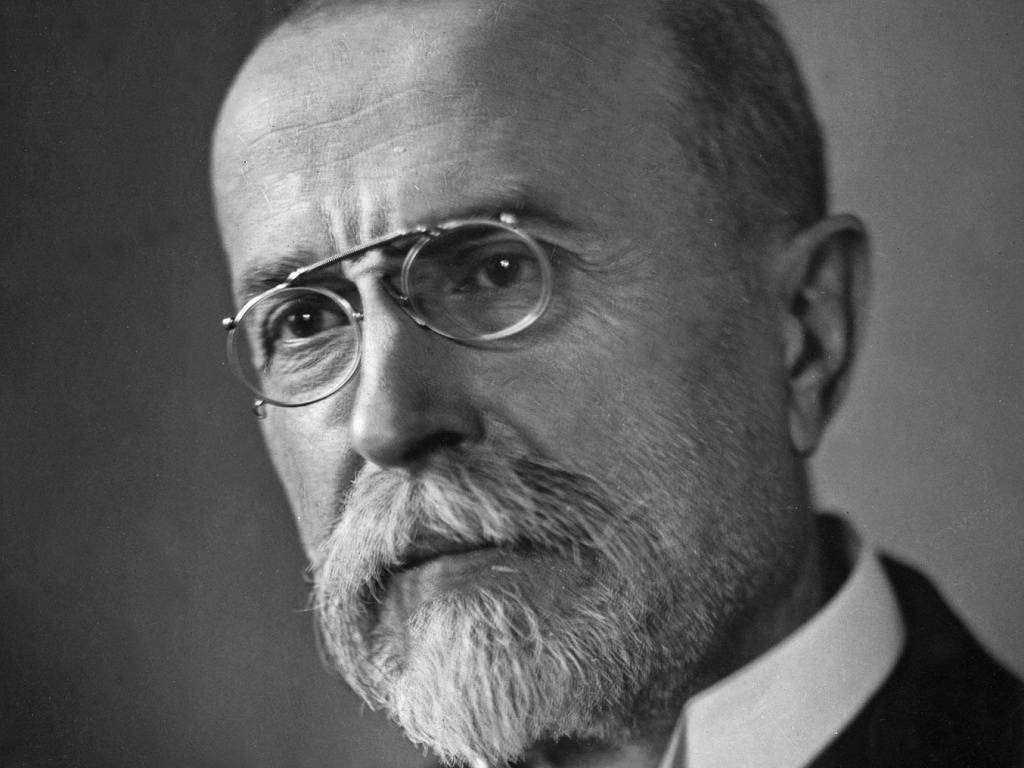

Václav Budovec (August 28, 1551 – June 21, 1621) was a Czech politician, diplomat, writer, and traveler. He was significant figure of the political and ecclesial life of the Czech people. He was born to a family belonging to the lower Bohemian nobility and was in favor of the idea of the Protestant Unity of Brotherhood, a religious society that placed an extraordinary emphasis on education.

As a young man he studied at the Protestant university in Wittenberg and boisterous student life he apparently liked – he continued, ‘the way round “after universities in Germany, the Netherlands, France and England, so he studied a total of twelve years. After studying, he traveled to the Protestant countries of Europe, visited the Netherlands, France, England, Denmark, and spent a year in Italy.

From 1577 to 1581, he worked as a diplomat in the diplomatic service as a deputy ambassador of the Viennese imperial court in the Turkish capital of Constantinople. During his stay in Turkey, he devoted himself to the study of the Koran and Turkish (Ottoman) history. There he added Turkish and Arabic to many of the languages he spoke and wrote-and he used this knowledge to thoroughly study Mohammedan customs and beliefs.

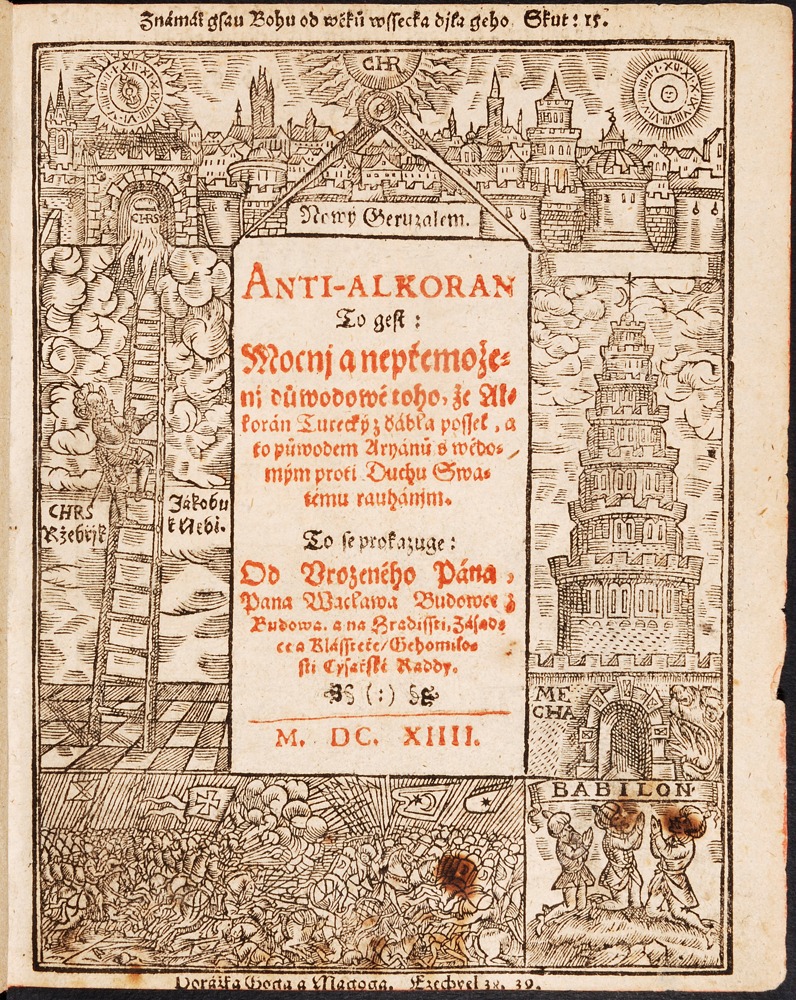

In 1593 he wrote about his reaction to his stay there, and in 1614 he published Anti-alkorán or its full name Anti-alkoran, tj. mocní a nepřemožitelní důvodové toho, že Alkoran turecký z ďábla pochází (Anti-alkorán, ie. The powerful and invincible explanatory that Alkoran Turkish comes from the devil), a religious-political text calling for the unification of all Christian churches for their struggle against Islam.

The first version was created in 1593, but censorship did not allow the release. The censors – most probably wrongly – saw the allegorical attack of the Protestant on the Catholics, so the second and revised version came out in 1614.

This book is important when looking at Islam as a culture, and religion in Czech environment. Antialkorán was one of the first books which were created at the territory inhabited by Czech speaking population and is focused on this topic.

I presume that for a proper understanding of Antialkorán it is necessary to pay attention to political and cultural events which are connected with a period in which mentioned book was written (1500s).

Upon his return to Bohemia, Václav Budovec became advisory to the council of appeals in 1584.

At the beginning of the 17th century, he publicly opposed the persecution of members of the Protestant Unity of Brethren and voiced his recognition of religious freedoms. In the following years, he became one of the most distinctive authorities of the Brethren Union in the Czech lands.

In 1608, he acted as an imperial commissioner during the war between Emperor Rudolf II of Habsburg and his brother, Hungarian King Matthias. In 1609, he was deeply involved in the issue of the “Majesty” of Emperor Rudolf II., A meeting that preceded the adoption of this document at the Czech Parliament, and then he described it as “Acts and Stories”.

Between 1618 and 1620, Václav Budovec belonged to the leaders of the ceského stavovského povstání. He was a member of the director and co-author of the texts of the second Estonian “Apologie”. After Friedrich Falcki’s accession to the Czech throne he became a royal chamberlain and president of the appellate court.

After the defeat of Czech lands, Emperor Ferdinand II. of Habsburg arrived. He ordered the execution of twenty-seven Czech lords and their property confiscated. One June 21, 1621 at Old Town Square, he was sentenced to death and executed as the second of the 27 executed leaders of the state in the so-called “Old Town Execution”.

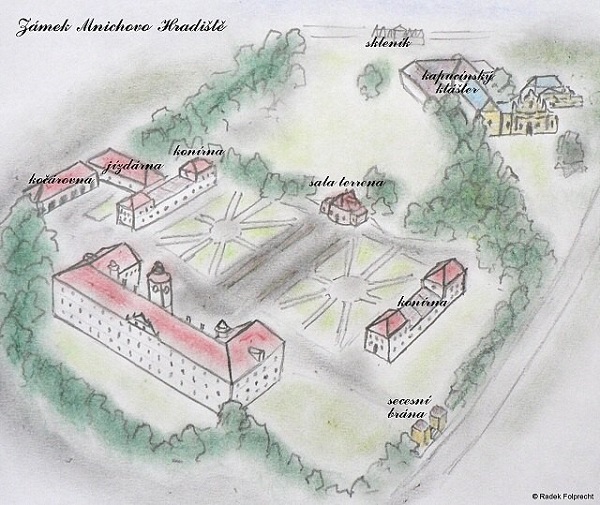

From 1602 until his death, Václav Budovec was the owner of the monastery on the grounds at what’s now referred to as Mnichovo Hradiště, which he inherited from his uncle Kryštof. Later, the estate of Zásadka and Klášter were also bought.

Taking care of and improving the estate was a pleasant change for him in the middle of political negotiations. He sought, in particular, to upgrade the entire city economically. He gave the burghers the privilege of 4 annual markets, more favorably regulated the inheritance law and granted 33 burghers the right to brew. Archives confirm his orders.

Another important achievement was the construction of the Renaissance chateau.

In the history of the city, Václav Budovec’s ownership represents an important stage. Citizens were always aware of this, and in the 1930s they created a sculpture by Karel Lidický and Josef Bílek. The statue is now located in the castle park.

The street was in Žižkov, between Koněvová and Roháčov.

Not far from Comenius Square, it was named in 1875.

Today the street longer exists.

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Become a friend and get our lovely Czech postcard pack.