American Czechs and their Religious Beliefs (1)

At the time of the mass migration of Czechs to America, according to the Austrian statistics, 960 Catholics, 22 Protestants, 16 Jews and less than 1 percent of agnostics lived in Bohemia, among 1,000 inhabitants. After they came to America, the statistics looked quite differently. Take for example the Czech inhabitants in New York, where one would find, according to Tomáš Čapek, 254 Catholics, 110 Protestants, 16 Jews and 620 agnostics among 1000 inhabitants. These numbers would correspond with the statistics from 1918, according to which the Catholic Benevolent associations had 32,908 members, as compared to 123,183 members in Non-Catholic associations.

It is indisputable that American Czechs become de-Catholicized. The universally respected Catholic historian, Father František Dvorník characterized the situation with the following words: “Most Czech immigrants brought with them from their native country antipathy towards the Catholic Church, which spread over Bohemia in the second half of the 19th century and many of them had given preference to Freethinking which ended up in apathy and anti-Clerical stand.”

Tomáš G. Masaryk expressed the substantiality of the religious liberalism among the American Czechs when he wrote:”It’s the freethinking from Bohemia that was brought on to the free American soil; a more radical freethinking from the fifties and the sixties, to be sure. It’s the freethinking of people who witnessed the revolutionary year of 1848, not only Havlíček’s freethinking, but also that of Dr. Rieger and also the freethinking of the younger Sabina, Sladkovský, Barák…. Whereas the freethinking in Bohemia ceased with liberal phrases and indolent Catholicism, the Freethinkers in America realized their strong beliefs more consistently and practically, they left the Catholicism…”

The question is how the de-Catholicization and liberalism came about? The argument that it was the result of the subversive conditions of American environment would hardly withstand, since it would contradict the experiences with Poles, who kept their Catholicism after they came to America, entirely without prejudice. The same could be said about the Slovaks. Maintaining that Czechs stayed away from churches for thrift reasons, so that they would not have to financially support the priests, that would not explain why they would support the non-Catholic Dominations. To explain it by materialistic thinking of Czech settlers, as Habenicht attempted to do, is absolutely unacceptable. Putting the blame on the offensive behavior of some priests would be difficult to believe, considering that most Catholic priests in America were admired for their tolerance and sacrifice.

The answer must be sought in the Czech past and, to some degree, in the character of the Czech people. Hardly any nation devoted greater attention to the religious question than Czechs and hardly any nation suffered more for religious reasons than Czechs. Nobody can argue with this solid reality, irrespective if it concerns a believer or an agnostic.

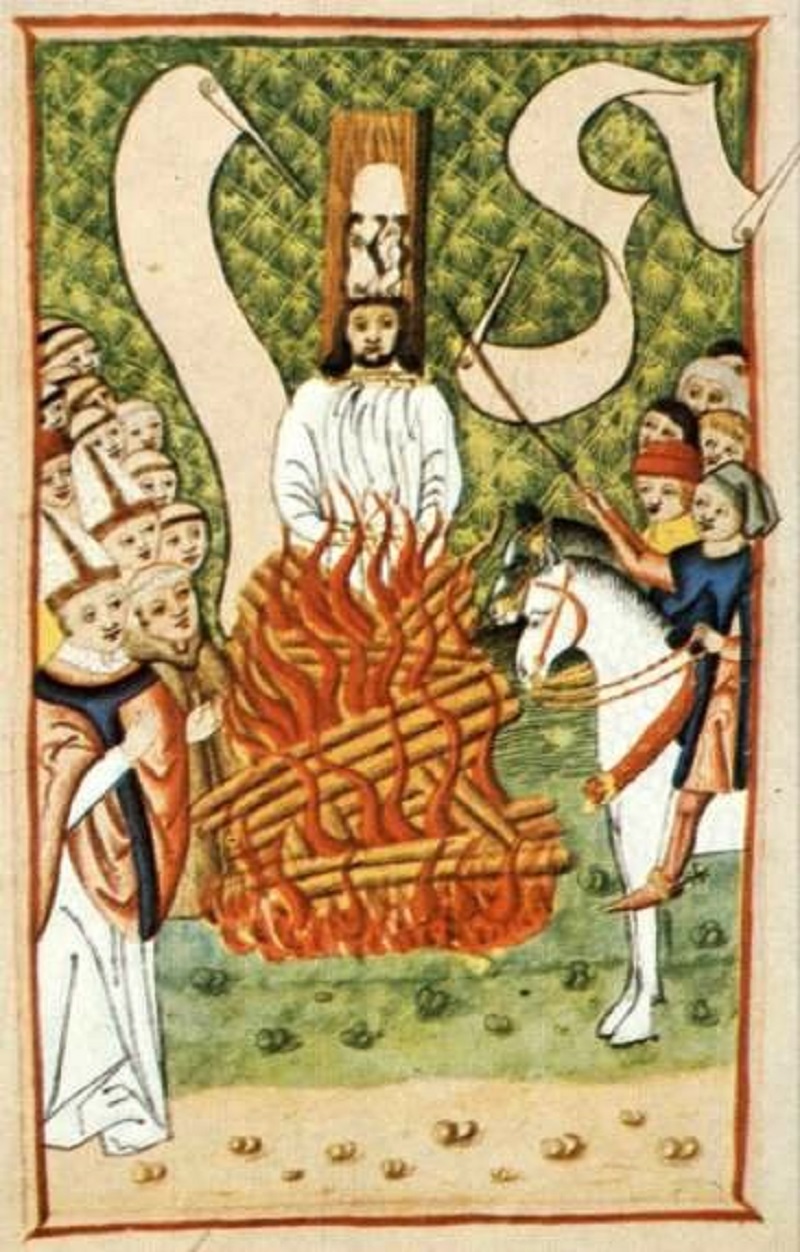

Jan Hus at the stake.

Bohemian history is woven with thoughts of spiritual thinkers and efforts of individuals and groups concerning introduction and maintenance of moral values, as well as with the reform of the eye-witnessed transgressions, perpetrated by some representatives of the organized Church.

Many of the thoughts and opinions of Czech thinkers and philosophers had influenced, for centuries, the development of the Western theology and philosophy and European civilization, in general. Bohemian spiritual thinkers were willing to stand behind their opinions fearlessly, regardless of the consequences. The martyr death of St. Wenceslaus, Jan Hus and Jan Nepomucký, to date are being thought of, symbolically, as examples of courage against wrongdoing and lawlessness, even at the price of one’s life. Their followers were willing to defend the views of their teachers and many of them lost their lives on the battlefield by the enemy’s army. The heroism of the half-blind Czech worrier Jan Žižka of Trocnov and the tragic departure of Jan Amos Komenský to exile, commanded respect and imagination of every Czech, regardless of his religious feelings.

Jan Žižka leading troops of radical Hussites.

It was for the religious reasons that led to the greatest tragedy of the Czech Nation, the defeat of the Bohemian Estates at the Battle of White Mountain. The cruel Habsburgs sought revenge upon the rebelling Czechs by setting up the humiliating public execution of the highest representatives of the Bohemian aristocracy, to frighten the Czech Nation from any further resistance. The execution of twenty-seven Bohemian leaders on the Old Town Square was the beginning of the reign of terror that the victorious Habsburgs brought to the Kingdom of Bohemia.

The victorious Habsburgs were determined to, forever, put an end to the ’Czech heretics’ through public executions, imprisonment, torture, confiscation of property and forced exile. The freedom of territorial rights was infringed by enforced centralization, Czech nationality was extirpated by Germanization, and the last remains of Czech Reformation were rooted out by the governing Catholic absolutism. The population was reduced to half, one third of the farmland was left untilled and the whole country became impoverished. The Habsburg rulers would rather have their lands desolate than inhabited by ‘heretics.’

Image by pruad.

This disastrous situation, lasting for three centuries, naturally left in the minds of the Czech people deep wounds, which could not be so easily healed. It was not just a question of a religious conviction but also a matter of national humiliation, in which the Catholic Church willfully took part. In this sense, de-Catholization of Czech immigrants in America, liberalism, ending in anti-Clericalism, was a natural outcome of the historical development. The idealized Czech leaders of the freethinking in America, were, most certainly, not obsessed with the notion of some vendetta against the Catholic Church, but rather, they were motivated by a genuine personal ideological conviction and desire to bring a better life and fate to the Czech people.

The first Czech spokesman for religious liberalism and rationalism in America was, without doubt, Vojta Náprstek, who, since 1852, was publishing in Milwaukee the weekly Milwaukie Flug-Blätter. He edited his paper in the anti-Clerical mode, and even though it was written in German, Czechs read it ‘voraciously.’ Náprstek was in full agreement with Havlíček’s views, in that the difference that in America he could dare write more openly than Havlíček could. The periodical Slavie, published by Karel Jonáš, to a degree, continued in this tradition.

Vojtěch Náprstek (often called Vojta) (April 17, 1826 – September 2,1894)

To quiet down the ultra liberal readers, Jonáš, together with Alois Kareš, decided to start a new periodical, Pokrok. Under the editorship of Josef Pastor, stiff-necked collisions occurred between him and equally unyielding priests, who, from the pulpit, admonished their faithful against the Freethinking atheists. When J. B. Zdrůbek, replaced him as an editor, the situation put an edge on. As a result of the editor’s clumsiness, it went as far as a law suit with pastor Vilém Řepiš, which left deep footprints in the ranks of the Czech community.

The Czech American Freethinkers began organizing around 1870. On October 5 of that year, the editor F. B. Zdrůbek wrote in his Pokrok periodical: “All zealots for the truth and the freedom in the entire America, on the day of the crushing fall of our freedom, even of the civil one, on November 8, gather to form the ‘Jednota’ (Union), which would give boost to our Nation, to get its former freedom and honor back!” According to Klácel, the origin of ‘Jednota’ dates to April 21, 1870, when he issued his proclamation in Slowan Amerikánský. “That was the first regiment, or the first revived root above the ground.” The Union was indeed established in 1870 and on the given day, November 8, on the memorable day of the tragic defeat of the Czechs at the Battle of White Mountain, 23 communities with 250 members, joined.

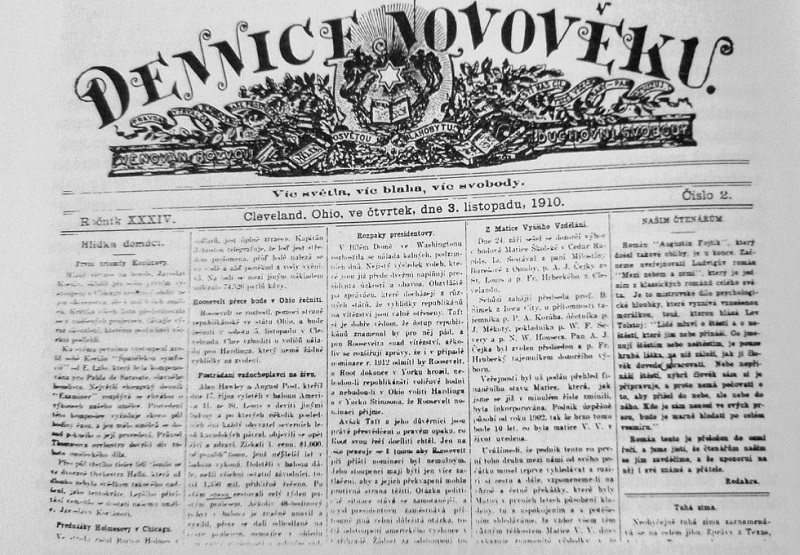

The followers of rationalism gained productive help when in 1875, Zdrůbek, together with August Geringer, in Chicago, founded the daily Svornost. Two years hence, Šnajdr’s periodical, Dennice Novověku, joined in similar spirit. During the latter’s foundation, the publisher Kořízek informed the readers: “Together with Mr. Šnajdr, I have established Dennice Novověku, the organ of radicals and the Freethinkers, in general, with firm belief that I have done my duty, as dictated to me by my conscience.” Václav Šnajdr remained active as editor of Dennice Novověku, continuously, for thirty-three years, while Zdrůbek worked a total of thirty-five years, as editor of Svornost. The readership and the influence of both papers transcended, by far, the border of the city. Until the ČSPS established its own newsletter, Dennice Novověku had been their official organ, as well as the organ of the women’s benevolent society, ‘Jednota Českých Dam’ (Union of Bohemian Women), which, no doubt, added to a greater influence of the Freethinkers.

Dennice novověku.

If one takes into account the number of Czech papers that supported the Freethinkers’ movement, starting with Náprstek’s Milwaukie Flug-Blätter up to Pastor’s Pokrok, Klácel’s Hlas Jednoty Svobodomyslných, Čapek’s Díblik, Zdrůbek’s Svornost, Bittner’s Šotek and Iška’s Vesmír, their influence must have been phenomenal. Besides the periodicals, book and pamphlet literature also had contributed for the promotion of the Freethinker’s movement, e.g., humorist books about the creation of the world, Ingersoll’s lectures, Paine’s Věk rozumu (Rise of Reason), Strauss’ Život Ježíšův (The Life of Jesus), amusing biography of St. Anthony, Voltaire’s works, as well as those of Buechner, Hassaurek’s and Volney’s.

It is a great pity the conflict between the Freethinkers, on one hand, and the Catholics, on the other, had gone so far. It was unnecessary. The situation went so far that the entire Czech American community was polarized into two camps and the majority of the Czech inhabitants had to choose for this or that side. Who knows how far these confrontations would have gone, if the First World War had not appeared on the horizon, and with it the opportunity for the liberation of the Czech Nation from the Austrian yoke. The situation led to the point that the Freethinkers and the Catholics finally forgave each other, shook hands and, with joint determination, side by side, collaborated in the liberation of the Czech Nation.

I don’t want to imply in this discourse that the Czech American Freethinkers were the good boys, while the Czech American Catholics were the bad boys. There were some good people, on both sides. It was actually the Czech Catholic priest, Father Oldřich Zlámal, who found a way making the adverse sides cooperate toward a common goal of establishing independent Czechoslovakia. Another Czech American priest, John Nepomucene Neumann, the founder of parochial education, was later declared the first male Saint in America.

St. John Nepomucene Neumann.

In conclusion, let me say a few words about the character of Czech people. I categorically reject the stereotypical view, coming mainly from ill-disposed people, that Czechs are godless men, anti-Clerical, “decayed to bone by impiety,” people without emotions and without feeling. Czechs are just the opposite! Majority of Czechs are idealistic people, meditative, and deeply religiously rooted, even though they may not attend church.

Longing for freedom, for justice, for truth, humanity and morale are the genuine roots of the Czech character and indivisible part of the Czech historical traditions, which, for centuries, had kept the Czech Nation alive and, thanks to these traditions, the Czech Nation lives on…!

Addendum

The above discussion does not, of course, pertain to the members of Moravian Church or to the Bohemian Jews. Nevertheless, the situation within these two-major religious denominations did not, in any way, change the overall conclusion reached about the religious nature of Czech people. If anything, it strengthens the point I have made.

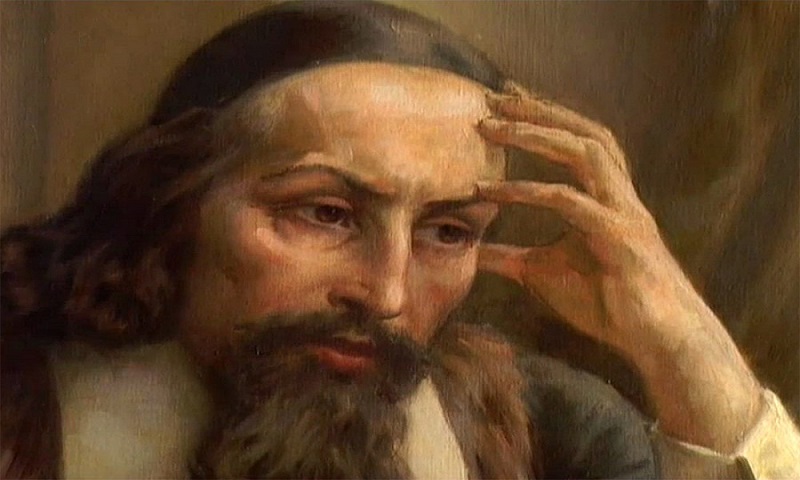

Moravian Brethren – The Moravian Church, as explained earlier, evolved from the ancient Unitas fratrum bohemicorum, whose members, known as Bohemian Brethren, were adherents and the followers of the teachings of the Czech martyr Master John Hus and John Amos Komenský (Comenius). Following the tragic Battle of White Mountain in 1620, the vengeful Habsurgs did not allow the Brethren to worship in their faith and they, in fact, outlawed their Church. Comenius, who held the position of the last Bishop of the outlawed Church, was forced to leave for exile and seek refuge abroad. This eminent European scholar was later offered Presidency of Harvard College in America, which would have made him the first Czech immigrant in America.

John Amos Komenský (Comenius).

Unfortunately, he did not accept. The followers of his Church went underground and, some 100 years later, they escaped from the Czech lands to Lusatia, Saxony, where they found a temporary refuge and where they resurrected their faith in the renewed Church which they named Moravian, in honor of the Comenius who was a native of Moravia. Because of the worsened situation in Saxony, they later immigrated en masse to America, where they established their distinct religious communities in Georgia, Pennsylvania, Ohio, North Carolina and elsewhere. (2)

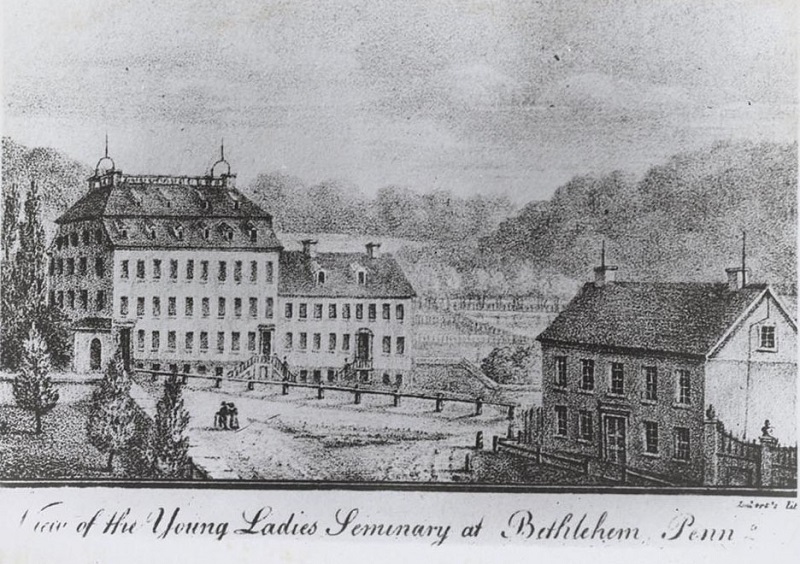

In America, they devoted their lives to missionary work among the Indians and black populations. These highly devoted people to their faith were all pacifists. Their Church, which has developed into an international institution, has had rather rigid, almost Puritan-like rules, which made some of its members change their affiliation to another Protestant faith. This was rather rare, however. The bulk of the Church’s members remained faithful to their creed and the Moravian Church, generally, has been expanding. Moravian Church has played an important role in the development of the United States. Among other, it has promoted higher education. Their Moravian College traces its roots to the Bethlehem Female Seminary, founded in 1742, as the first boarding school for young women in the US. (3) Harvard University, in comparison, did not admit women until the end of the 19th century! Moravian women, generally, played an important, if not a key role in the affairs of the Moravian Church and, frankly, they were ahead of American suffragists by a hundred of years. (4)

Bethlehem Female Seminary.

Bohemian Jews – As for the Bohemian Jews in America, their situation and attitude was similar to that of the Moravian Brethren. After coming to the US, they all maintained their faith and, if anything, their bond to Judaism in America became stronger than it was in their native country. In fact, it was their faith, which kept them together and sometimes separate from the Jewish groups of other nationalities. (5)

Jacob Block, was one of the first Blocks of a large family of Bohemian Jews to land in America, who briefly lived in Baltimore, Maryland, and Williamsburg, Virginia, before settling permanently in Richmond, Virginia. In Baltimore, he had been a grocer; in Richmond, he became a merchant. He was very active in Jewish affairs and before his death, in 1835, he had served as president of Beth Shalome, the only Jewish congregation in Richmond at the time.

Almost upon their arrival, Bohemian Jews began to organize their own distinct congregations, such as was the case in New York City, St. Louis, Milwaukee, Newark, or Chicago. Apart from different philosophies, their distinct congregations were conditioned by the fact that most Bohemian Jews came generally from affluent families and were highly educated, when compared, for example, to East European Jews.

As for New York City, it is noteworthy that, already in 1848, the New York Czech Jews had their own congregation ‘Ahabath Chesed Böhmischer Kultus.’ Their synagogue stood on 133 Ridge Street and their burial ground in Cypress Hill Cemetery. Their first rabbi was Falkman Teberich, while Ignatz Stein served as president of the congregation. It became Central Synagogue in 1917, designated as NYC Landmark in 1966 and a National Historic Landmark in 1975.

The Central Synagogue is located at 652 Lexington Avenue on the corner of E 55th Street, Manhattan, New York City, New York.

The parent organization, recorded, as early as 1846, was not a synagogue but a mutual aid society, called ‘Bohemian Brethren.’ This society was mentioned in the minutes of Emanu-El Congregation in New York of May 30, 1847, under the name of ‘Bőhmischer Verein.’ Simon Klauber was president, Charles S. Kuh vice-president, Dr. Brockman as treasurer and M. Opper was secretary. (6)

In St. Louis, its pioneer Jew was Wolf Bloch, a native of Švihov, Bohemia, who was reported to have settled there in 1816. The United Hebrew Congregation, founded in St. Louis in 1837, a mere fifteen years after the incorporation of the City of St. Louis, was the first Jewish congregation established in St. Louis and was the oldest west of the Mississippi River. The chief organizers of the minyan were Abraham Weigel and Nathan Abeles, both natives of Bohemia, who were to become the first president and secretary of the United Hebrew Congregation, when it was legally organized four years later, on October 3, 1841. In 1854, the congregation elected the first rabbi ever to serve in St. Louis. He was a Bohemia –native, Rev. Dr. Bernard Illowy, one of the foremost Orthodox rabbis in the country.

The B’nai B’rith synagogue in St. Louis, Missouri was founded by the Bohemian Jewish leader Daniel Block (1802–1853). He lived for only four years in the United States but he made important contributions on the culture of the St. Louis Jewish community to which he belonged. Between his arrival in about 1848, and his death in 1853, he contributed greatly to the organization and development of B’nai El Congregation. His actions were described in some detail in Zion in the Valley. (7) This congregation was known as the ‘Bohemian Shul,’ as it was founded by German speaking Bohemian Jews who lived in the southern part of St. Louis. Daniel Block was named as the ‘first parnass’ and referred to as ‘the father of the B’nai B’rith Congregation.’

The St. Louis Congregation Shaare Emeth, in turn, was organized on 17th and Pine, with Rabbi S. H. Sonneschein (1839-1908), who received his rabbinical training in Prague, as its spiritual leader. In 1886, a number of the members, being dissatisfied, banded together, and with Rabbi Sonneschein organized Congregation Temple Israel, with Isaac Schwab as president.(8)

In Newark, NJ, Bohemian Jews established, in 1860, their ‘Böhmisch Schul,’ Oheb Shalom (Lovers of Peace) Conservative Congregation and Synagogue, then located on Prince Street in Newark, New Jersey. Its 1884 Moorish Revival building, known as Prince Street Synagogue is now listed on the National Register of Historic Places.(9)

Later on, they even established their own cemetery, Oheb Shalom Cemetery, located at 1321 North Broad Street in Hillside, NJ. As we learn from its history, “At the close of the nineteenth century, a group of congregants from Oheb Shalom, then located on Prince Street in Newark, NJ, led by Emanuel Abeles, Isidore Grand and Meyer Kussy decided to acquire land to develop a conservative Jewish cemetery. They settled on a three-acre parcel in Hillside, New Jersey. They organized a board, Manny Abeles was elected chairman and dividing the land into available plots, developed a fee arrangement including perpetual care and planned for a Chapel House that would accommodate funerals and also house a groundskeeper and his family on the second floor.”

In Milwaukee, on Yom Kippur in 1847, 12 Jewish pioneers held their first services at the home of Bohemia-native, Isaac Neustadtl at Chestnut and Fourth Streets, leading to the establishment, in 1850, of Emanu-El, the first Jewish congregation in Milwaukee. Solomon Adler, who was a Bohemian Jew, became its first president.(10) In 1849, the congregation transferred its services to the home of Nathan Pereles. This Bohemian congregation, the oldest Jewish congregation on Milwaukee and Wisconsin, later merged with a younger congregation Avath Emunah and formed the B’ne Jeshurun under the presidency of Nathan Pereles.(11)

In Chicago, the Bohemian Jews constituted a distinct group; they were too far advanced in the religious views to join the orthodox group, and too conservative for Reform Judaism. Hence, they formed in 1870 a congregation of their own, B’nai Abraham, and erected a house of worship on the corner of Brown and Henry Streets. Rabbi Abraham R. Levy ministered to their spiritual needs. In 1921, it combined with Zion Congregation.

Another non-Orthodox congregation, B’nai Jehoshua,’ at the 19th and Ashland Streets on the fringe of the Maxwell Street area was organized in 1893 by Bohemian Jews, who wished to live near their small stores on 18th and 22 Streets in the Gentile Bohemia neighborhood of Pilsen. (12)

In Michigan, Solomon Weil (1821-1891), immigrated from Bohemia in 1845, followed by other members of the Weil family, settling in Ann Arbor, and forming the Jewish nucleus in the city. Minyanim services, first held in Michigan, took place in their house. Their father Joseph Weil (1777-1863) served a Rabbi.

In Cleveland, Bohemian Jews belonged among the pioneers of te city Jewish community. The Bohemian Rabbi, Josef Levy (born in 1797), from Písek, was trained in the Orthodox Schools in Prague and ordained by rabbis from Písek and Březnice. In Cleveland he made livelihood in the grocery business and served every Sabbath, without renumeration, to the needs of the Jewish congregation.

In 1850, when the first Reform synagogue, Temple-Tifereth Israel, was formed in Cleveland, the Prague-educated Isadore Kalisch (1816-1886), became its first rabbi, followed by Rabbi Aaron Hahn (1877-1892) and then by Rabbi Moses Gries (1868-1918), both of whom were Bohemian Jews. Under the leadership of Rabbi Moses J. Gries, during 1892-1917, Tifereth Israel became one of the leading congregations in the US.

On August 12, 1884, the Bohemian Congregation was officially incorporated in Cleveland, by Simon Metzel, Markus Koblitz, Solomon Pollock, Louis Adler and Charles Lederer, as the Bohemian Chebra Kaddischa (Burial Society) Church Association. In 1916, the Congregation had 80 members in addition to a women’s auxiliary known as the Sisterhood, over 60 ladies. There was an unofficial (un-recorded) name change to ‘Chevera Kadisha – Temple Israel,’ as they as well as other Synagogues moved from the orthodox practices of Judaism to the reform movement.

In Arkansas, Abraham Block (1780-1857) was the patriarch of the first documented Jewish family to immigrate to the the State of Arkansas (1823). Anshe Emeth Congregation organized in Pine Bluff in 1867, invited that year as its first rabbi Bohemian Jew, Jacob Bloch (1846-1916), who served from 1867 till 1871. Subsequently, he became Rabbi at Little Rock, AR (till 1880), prior to mving to California.

Despite their small count, a number of Bohemian rabbis were quite influential in the US, some of them assuming a leadership role. This was the case of Rabbi Isaac Myer Wise, a native of Lomnička, Bohemia, who is considered Father of the Reform Judaism in the US. When, upon his arrival in America in 1846, he was appointed Rabbi of the Congregation Beth-El of Albany, he soon began agitating for reforms in the service. His was the first Jewish Congregation in the United States to introduce family pews in the synagogue. Wise introduced other innovations, including confirmation, a mixed-gender choir and counting women in forming a minyan or religious quorum. During his lifetime, Isaac M. Wise was regarded as the most prominent Jew of his time in the United States. He was instrumental in organizing the Union of American Hebrew Congregation (1873) and in founding Hebrew Union College (1875), which he served as president until his death. In 1889, he also founded the Central Conference of American Rabbis and served as its president until the end of his life. (13)

Rabbi Isaac Mayer Wise (29 March 29, 1819 – March 26, 1900).

Bernard Illowy (l812-1871) from Kolín, Bohemia was probably the second most influential rabbi in America of Czech ancestry. He was an orthodox rabbi and scholar educated at the rabbinical school in Padua and the University of Budapest. At time of his immigration to US in 1848 he was the only Orthodox rabbi to hold a doctorate degree in the US. He served as rabbi in New York, Philadelphia, St. Louis, Syracuse, Baltimore, New Orleans and Cincinnati. He stressed Orthodox observance in his sermons and was a powerful speaker, accomplished lyricist, and great Talmudist. (14)

The third rabbi of significance was Maximilian Heller (1860-1929), a native of Prague, who was educated in Prague and Cincinnati. He became rabbi in Chicago (1884-86), Houston (1886-87) and of the Temple Sinai in New Orleans (s. 1887), where he served for more than 40 years. He was active in communal affairs and in 1912 was appointed professor of Hebrew and Hebrew literature at Tulane University, where he served until retirement in 1928. He was a Charter member of Central Conference of American Rabbis, serving as their president from 1911-29. (15)

Samuel Wolfenstein (1841-1921), a native of Moravia, was educated at the universities of Vienna, Prague and Breslau. He received his ordination from Rabbi Zvi Mecklenburg of Koenigsberg in 1865 and duly served as a congregational rabbi in Insterburg, Prussia for five years. He and his wife, the former Bertha Brieger, immigrated to the US, where they he shortly applied and was accepted to the post as rabbi of B’nai El congregation, St. Louis. In 1878, he resigned from B’nai El to become superintendent of the highly regarded orphan home established in Cleveland by B’nai B’rith.(16)

Stephen S. Wise (1874-1949) was a descendant of a long line of rabbis in Moravia in the 17th and 18th centuries. After immigration to New York as a child and after his ordination as a Reform rabbi, he led a congregation in Portland, Oregon, where his liberal political convictions inspired him to fight for child labor laws and for the demands of striking workers. A charismatic orator, he became a champion for social justice and civil rights and was one of the founders of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. He later became a strong advocate and vocal supporter of Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s ‘New Deal.’(17)

Mention also should be made of Samuel Weltsch (1835-1901), from Prague, who descended from a family of hazzanim (cantors). While a young man he became cantor of the Meisl Synanogue, which was an outstanding among the synagogues of Prague, In 1865 he received a call from congregation Ahabath Hesed of New York, and remained its cantor until 1880 when he returned to his native city. During his stay in in New York, he was active in improving the musical service of the American synagogue and was one of the collaborators on the first three volumes of Zimrat Yah, a collection of music for all the seasons of the year.

Other rabbis of note included Emanuel Schreiber (1852-1932), Gotthard Deutsch (1859-1921), Moses J. Gries (1868-1918), Eugene Kohn (1887-1977, James G. Heller (1892-1971), and Leo Jung (1892-1977).

Compared to other Jewish groups, the contribution of Bohemian Jews to America have been phenomenal and extraordinary.

The notion, that the Bohemian Jews in America lived separate life from the rest of the Czechs in the US, would be a wrong conclusion, considering the fact that it was Congressman Adolph Sabath and Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, both Bohemia-born Jews, who were instrumental in convincing President Wilson to change his policies leading to the creation of independent Czechoslovakia in 1918.

Notes:

(1) Information about this topic can be found in the following publications: Tomáš Čapek, “Rationalism: A Transition from the Old to the New,” in: The Čechs (Bohemians) in America. Boston and New York: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1920, pp. 119-136; Tomáš Čapek, “Čechoameričan Reformátor: Racionalism,” in: Naše Amerika. Praha: Nákladem Národní rady československé, 1926, pp. 362-371; Lev Palda, Myšlenky o novém náboženství. Omaha, 1902; Jan Rudiš-Jičinský, Historical Sketch of Bohemian Free Thought in the United States. Cedar Rapids, IA: Free Thought Society, 1908; T. G. Masaryk, “Svobodomyslní Čechové v Americe,” Naše doba (Praha), 20. října, 1902, pp. 1-7; J. E. Salaba Vojan, “Why Should We American Čechs Be Liberal-Minded?,” in: Czech Reader. Ed. By Vojta Beneš. Prague, 1912, pp. 425-428; E. F. Prantner, “Free Thinkers-American Czechoslovaks,” in: The Czechoslovak Review 6, No. 7 (1922), pp. 174-177; J.E. S. Vojan, “Racionalismus a jeho budoucnost, Svojan 43, No. 12 (Prosinec 1937), pp. 177-180; “One Hundred Years of the Bohemian Freethinkers in Chicago,” in: Panorama. A Historical Review of Czechs and Slovaks in the United States of America, 1970, pp. 82-84; Karel D. Bicha, “Settling Accounts with an Old Adversary: The Decatholization of Czech Immigrants in America,” Social History 4 (November 1972), pp. 45-60; Bruce M. Garver, “Czech-American Free Thinkers on the Great Plains, 1871-1914,” in: Ethnicity on the Great Plains. Ed. Frederick Luebke. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1980, pp. 147-59; Richard Samuel Schneirov, “Free Thought and Socialism in the Czech Community in Chicago, 1875-1887,” in: Struggle a Hard Battle. Essay on Working Class Immigrants. Edited by Dirk Hoerder, DeKalb, IL: Northern Illinois University Press, 1986, pp.121-142.

(2) Miloslav Rechcigl, Jr., “The Renewal and Formative Years of the Moravian Church,” Czechoslovak and Central European Journal 9 (19990), pp. 12-24.

(3) “Moravian College,” in: Wikipedia. See: https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Moravian_College

(4) Miloslav Rechcigl, Jr. “Czech (Bohemian) Women in US History. Independent Spirit and their Nonconforming Role,” Kosmas 35, No. 1 (Fall 2011), pp. 102-139.

(5) Guido Kisch, In Search of Freedom. A History of American Jews from Czechoslovakia 1592-1948. London: Edward Goldston, 1948; Miloslav Rechcigl, Jr., “Early Jewish Immigrants in America from the Czech Historic Lands and Slovakia,” Rev. Soc. History Czechoslovak Jews 3 (19990-91), pp. 157-70.

(6) The American Synagogue: Historical Dictionary and Sourcebook. By Kerry M. Olitzky, Marc Lee Raphael. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996.

(7) Walter Ehrlich, Zion in the Valley. The Jewish Community of St. Louis. Volume 1. 1807-1907. Columbia and London: University of Missouri Press, 1997.

(8) “History of Jewish Americans in St. Louis,” in: Wikipedia. See – https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/History_of_Jewish_Americans_in_St._Louis

(9) “Oheb Shalom Congregation,” in: Wikipedia. See – https://en.wikipedis.org/wiki/Oheb_Shalom_Congregation; “Prince Street Synagogue,” in: Wikipedia. See- https://en.wikipedia/wiki/Prince_Street_Synagogue

(10) History of Milwaukee, Wisconsin. Chicago: The Western Historical Company, 1881, vol. 2; Louis J. Swichkow and Lloyd P. Gartner, This History of the Jews of Milwaukee. Philadelphia: The Jewish Publication Society of America, 1963.

(11) The overwhelming majority of Jews in Milwaukee who founded Congregationj B’ne Jeshurun were Bohemian. Among the families that were prominent in the community in the 19th century were Oplatka, Rindskopf, Schram, Patek, Herbst, Eckstein, Greenhut, Teweles, Karpeles, Pereles, Polachk, Schefteles, Stransky, Fischel., all of Bohemian background.

(12) The Jews of Chicago: From Shtetl to Suburb. By Irving Cutler. Chicago: University of Illinois, 1996, p.100.

(13) Max B. May, Isaac Mayer Wise. The Founder of American Reform Judaism. A Biography. New York-London: G.P. Putnam’s Sons, 1916; Isaac M. Wise, Reminiscences. Cincinnati: Leo Wise & Co., 1901.

(14) Cyrus Adler, Gotthard Deutsch,”Illowy, Bernard,” in: Jewish Encyclopedia. New York: Funk and Wagnalls Co., 1904, Vol. 6, p. 561; Chuck Jackson, “Rabbi Bernard Illowy,” Generations, 10, Issue 4 (April 2004), pp. 6-7; “Illowy, Bernard (181-1871),” in: Orthodox Judaism in America. By Moshe D. Sherman. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1996, pp. 101-103.

(15) Barbara S. Malone, Rabbi Max Heller, Reformer. Zionist, Southerner, 1860-1929. Tuscaloosa, AL: University of Alabama Press, 1997.

(16) Gary Edward Polster, “Dr. Samuel Wolfenstein. The Beginning of an Era,” in: Inside Looking Out: The Cleveland Jewish Orphan Asylum, 1868-1924. Kent: Kent State University Press, 1990, pp. 25-49.

(17) Stephen Wise, Changing Years: The Autobiography of Stephen Wise. New York: G. P. Putnam’s Sons, 1949; Melvin Urofsky, A Voice that Spoke Justice. The Life of Times of Stephen S. Wise. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1982.

Guest Post Author

Mila Rechcígl

Miloslav Rechcígl, Jr. is one of the founders and past Presidents of many years of the Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences (SVU), an international professional organization based in Washington, DC.

He is a native of Mladá Boleslav, Czechoslovakia, who has lived in the US since 1950.

Read his entire profile here. Discover Mila’s many books on Amazon.

Thank you in advance for your support…

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

We appreciate you more than you know!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

Interesting stuff, thanks.

It’s astounding to think a place that fought the 30 years war over religion is now mostly atheist.

Proud to be a Czech-American!!!!