Yes, love inspires music. At 63, Czech composer Leoš Janáček met his Moravian muse, Kamila Stösslová, and through years of writing to her and composing as a way to further experess his feelings, his greatest works were created. Sometimes the words we say are not as important or as telling as the words we write in private. Love letters share feelings from our most intimate depths and are usually meant for only one other, to whom they are addressed. But it just so happens that every now and again, they find their way into the hands of others and are thus able to paint a new portrait. These are such letters of a great love story whose life existed primarily in the music it inspired.

Almost every summer after 1903, Leoš Janáček went alone to the Moravian spa town of Luhačovice, to take in the countryside and enjoy the healing spa waters. Fate stepped in some time between July 3rd and July 7th of 1917, and he met an interesting 25-year old woman, Kamila Stösslová.

Leoš fell deeply in love with her, despite the fact that they were both married and that he was almost forty years older than she. She became the sole focus of all his erotic feelings, fantasies and passions for the rest of his life.

The Moravian Muse

Because of his love for her and the 700+ love letters they exchanged, Kamila Stösslová (born Neumannová; 1891–1935) holds an unusual place in music history.

Because of his love for her and the 700+ love letters they exchanged, Kamila Stösslová (born Neumannová; 1891–1935) holds an unusual place in music history.

Kamila was living in Luhačovice with her husband, David Stössel, and their two sons, Rudolf and Otto. At that time, David was in the army and he assisted Janáček in obtaining vital food supplies during wartime.

Because David was enlisted and had to perform his army service, it left Kamila much time alone, thus giving Janáček opportunities to walk and converse with her on many occasions.

We know that Janáček arrived at the resort on July 3, 1917. By July 8th, he wrote a fragment of her speech in his diary. Sending a brief note on July 24, 1917, his correspondence with Kamila had begun.

She was a profound influence on the composer in his last decade.

“You stand behind every note, you, living, forceful, loving. The fragrance of your body, the glow of your kisses – no, really of mine. Those notes of mine kiss all of you. They call for you passionately…“

Kamila was very passive and quite ambivalent about his feelings for her. Yet for Janáček the muse had awakened.

It was Kamila who inspired him to create the lead characters of three of his operas; the vixen in The Cunning Little Vixen, Emilia Marty in The Makropulos Affair and Káťa in Katya Kabanová. Other works were also inspired by his passion for her, including Glagolitic Mass, Sinfonietta, The Diary of One Who Disappeared and String Quartet No. 2 (appropriately subtitled Intimate Letters) which was written in 1928. String Quartet No. 2 has been referred to as Janáček’s “manifesto on love”.

When they met, he was sixty-three and locked in a loveless marriage; she was a mere twenty-six, the wife of a man who was frequently away from home. After the week at the spa, Janáçek began writing to Stösslová and over 700+ letters were eventually exchanged between them. Though this was not your ordinary love story.

Janáček kept the relationship alive on nothing more than his own fantasy and desire.

The Lonely Composer

Leoš Janáček

There was nothing ordinary about Czech composer Leos Janáček. He set one opera in a barnyard and another on the moon. He fell heavily for a married woman more than 30 years his junior, and proceeded to write her more than 700 love letters. Most of the letters reveal a realization that the composer’s love for Kamila was unrequited.

“My life is sadder, more disordered, which is why I bind it with this ‘art’ of mine, I glue it together, I re-create it in my imagination more tolerably for myself. Who knows, if fate had united us closely, whether I would have needed this art, whether it would ever have made itself felt within me at all? Whether in your eyes which look on so sincerely there wouldn’t have been the whole world for me?”

Completely undeterred by her lack of interest in his work and her spasmodic replies, he continued to compose while sending her letters until his death eleven years later.

In short, he was obsessed with the young woman. A woman who in the beginning, barely answered him. Yet he continued to write, and to compose some of his greatest works. In fact, it was when he was in his mid-60s that he churned out piece after amazing piece in one of classical music’s most impressive late surges.

We now know that the attention Janáček paid Kamila was primarily expressed through his letters. The initial flow of correspondence was heavy, as if she had lit a spark within him. His were the letters of a lonely old man whose fantasies about Kamila as his soulmate and true “wife” truly fueled the inspiration of his greatest works. He writes:

Dear soul

Believe me, I cannot escape from our two walks. Like a heavy, beautiful dream; in which I am bewitched.

I know that I’d be consumed in that heat which cannot catch fire. On the paths I’d plant oaks which would endure for centuries; and into their trunks I’d carve the words which I shouted into the air. I don’t want them to be lost, I want them to be known.

To no-one, ever, have I spoken these words with such compulsion, so recklessly: ‘You, you, Kamila! Look back! Stop!’ and I read in your eyes as well that something united us in that gale-force wind and heat of the sun. Perhaps something was fated to give us both unutterable pleasure? Never in my life have I experienced such an intermingling of myself with you. We walked along not even close to one another and yet there was no gap between us. I was just your shadow, for me to be there it needed you. I’d have wished that walk to be without an end; I waited without tiring for the words which you whispered; what would I have done were you my wife? Well, I think of you as if you were my wife. It’s a small thing just to think like that, and yet it’s as if the rays of a hundred suns were overwhelming me. I think this to myself and I won’t stop thinking it.

Do with this letter, this confession of mine, what you will. Burn it, or don’t burn it. It brings me alive. Even thoughts become flesh.

(Source: Quilldrivers)

The feeling in his letters served to expose an extraordinarily self-revealing portrait of an isolated artist at the height of his creative powers and the beginning of his international fame.

Meanwhile, during this entire time, Kamila continued to remain emotionally aloof. Perhaps her inaccessibility is what made his obsession even stronger. He says it time and time again, it is what drove him to write and to compose. She inspired him to greatness and while she was not there for the relationship that existed in his mind, she was there with him when he died in 1928.

The last entry, from two days before he died, reads:

And I kissed you.

And you are sitting beside me and I am happy and at peace.

In such a way do the days pass for the angels.

Like most everything else, the letters were suppressed until changing conditions in Czechoslovakia allowed their full publication.

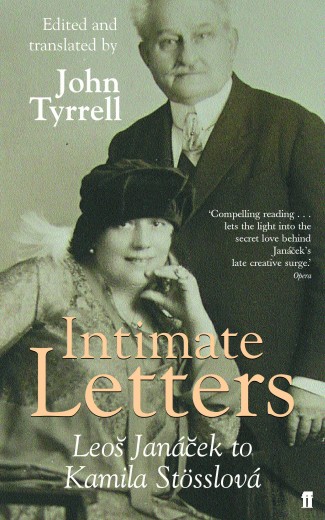

Originally published in 1994, you’ll definitely want to read Intimate Letters: Leoš Janáček to Kamila Stösslová by John Tyrrell.

Originally published in 1994, you’ll definitely want to read Intimate Letters: Leoš Janáček to Kamila Stösslová by John Tyrrell.

In this incredible book, John Tyrrell edited and translated a comprehensive selection of them, concentrating on the almost daily letters of the final eighteen months.

Supported by a diary of meetings between Janáček and Stösslová, a decoding of the erotic references in the letters, and a selection of mostly unknown photographs, this remarkable book breathes life into the story one of the greatest of operatic composers and provides vital clues to the nature of his creative genius.

“He was 63 and had been unhappily married. She was 25 and apparently dully, indifferently married. His infatuation was immediate and continued at high convection until his death 11 years later. His love was neither reciprocated nor consummated and she seldom even responded to his epistolary bombardment, yet most of his greatest music is about her. The letters are wonderful.” – The Washington Post

True Creative Genius

“Janáček was a choirboy at Brno and studied at the Prague, Leipzig, and Vienna conservatories. In 1881 he founded a college of organists at Brno, which he directed until 1920. He directed the Czech Philharmonic Orchestra from 1881 to 1888 and in 1919 became professor of composition at the Prague Conservatory. Deeply interested in folk music, he collected folk songs with František Bartoš and between 1884 and 1888 published the journal Hudební Listy (Musical Pages). His first opera, Šárka (1887–88; produced 1925), was a Romantic work in the spirit of Wagner and Smetana. In his later operas he developed a distinctly Czech style intimately connected with the inflections of his native speech and, like his purely instrumental music, making use of the scales and melodic characteristics of Moravian folk music.” – Encyclopædia Britannica.

Leoš Janáček was one of the most prominent personalities of the music of the first half of the 20th century. While Bedřich Smetana was praised for his genuine Czech musicality and is considered the greatest Czech composer, it was Janáček who was mostly misunderstood because of his attempt to capture the reality of life in music. Moving from brightness of fortune to the tragedy, from the ordinary to ceremonious and grand, many did not understand his music or the genius behind it.

Janáček also had a very strong personality. He openly expressed his views and thus had to reckon with the fact that what he shared often resulted in frequent criticism. His truest expression came through music, an area where he could freely express without any consequence. Through his music, we can now understand why Janáček is one of the world’s most spectacular, most interesting and most sought-after composers of the 20th century.

Below is the only film footage of Leoš Janáček, set to some of his late music. Though it is only seven seconds long, it serves to capture his brusque, hectic style never seen in photographs.

A documentary, In Search of Janácek (original title Hledání Janácka) was made for Czech television in 2003. The film, written and directed by Petr Kaňka, received Special Mention at the International Television Festival Golden Prague in 2003. It was officially released in 2004 to celebrate 150 years anniversary of Janáček. In it, the director combined archive footage with contemporary stagings.

We sure do wish this was on DVD!

The music of Leoš Janáček lives on and even if you do not listen to chamber music or attend theater or opera, you may have heard it in contemporary films such as Crown Court (1972) , The Unbearable Lightness of Being (1988), and Tomcat (2016).

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Become a friend and get our lovely Czech postcard pack.