Today we are honoring Helen Brooke Taussig, a woman physician who saved thousands of children’s lives.

When in May 1980, the famed 87- year physician, Helen Brooke Taussig, lost her life during a car accident, the Czech foreign press did not devote any attention to that event. Nobody could, of course, suspect that she was, on her father’s side, of Czech origin. The family name ‘Taussig’ occurs frequently in Bohemia and comes from ‘Taus’ which is a German term for the west Bohemian town of Domažlice.

Helena Taussig was an eminent woman who is generally considered the founder of pediatric cardiology and who is credited for saving thousands of lives of newborns and small children before a certain death. She came from a famous family of the American Taussigs, whose ancestors emigrated from Bohemia to America, at the onset of the 19th century.

Helen Brooke Taussig was born in Cambridge, MA, on May 24, 1898. As a small child, she suffered a serious case of dyslexia and she credited her father, Frank W. Taussig, a professor at Harvard University, for overcoming her immense difficulties while reading. Her mother died when she was only eleven years old. Her grandfather, a Bohemian Jew, William Taussig, who came from Prague, settled in St. Louis, MO. From meager beginnings he worked out to become a practicing physician and, later, one of the most influential businessmen and industrialists in the State of Missouri.

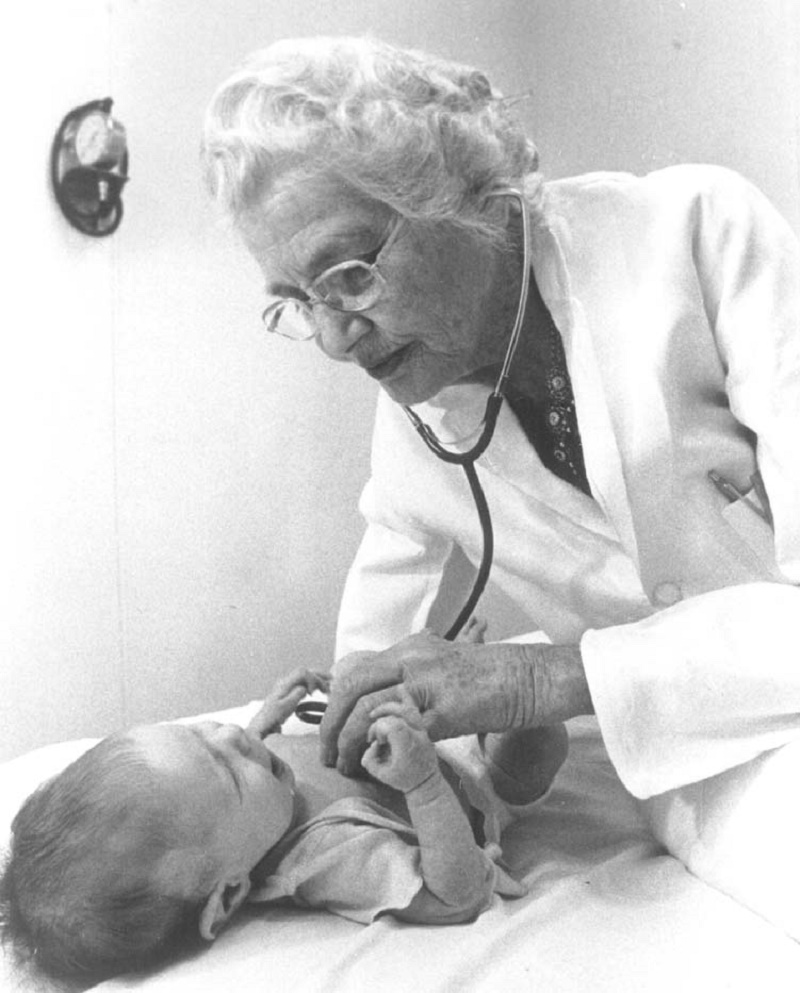

Taussig examining a blue-baby. Photograph by permission Hearst Newspapers.

Helena Taussig grew up in a university setting and spent her summers on a Cape Cod. In 1917-19, as one of the first women, whatsoever, she attended Radcliffe College, where she became a tennis champion. To broaden her horizons, she went to University of California at Berkeley, where she gained Bachelor’s degree. Afterwards she enrolled as a special student at the Medical Faculty of Harvard University, where the women were not admitted yet to regular university programs (until 1945). For some time she also studied at Boston University and, in 1924, she transferred to Medical School at Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, where she was accepted as a full-degree candidate. Already in the second year of her studies, she published her first scientific paper about the rhythmic contraction of heart muscles.

Helen Brooke Taussig completed her MD degree in 1927 at Johns Hopkins, where she then remained for one year as a cardiology fellow and for two years as a pediatrics intern. While at Hopkins, she received two Archibald Fellowships, spanning 1927-1930. Taussig began her career after her fellowship in cardiology with a stint as head of a rheumatic fever department. She then was hired by the pediatric department of Johns Hopkins, the Harriet Lane Home, as its chief, where she served from 1930 until 1963. Simultaneously she taught at Johns Hopkins University, where, in 1959, she became a full professor.

Portrait of Helen B. Taussig by Yousuf Karsh, ŠKarsh.

In her scientific work, Taussig began to be early interested in children’s heart diseases, especially the rheumatic fever, from which many children suffered. As the first, she began using a fluoroscopy during diagnostics, then entirely a new Roentgen method, to localize inborn heart malformations. It was exactly, by using this technique from various angles, when she discovered correlation between certain changes of the size and shape of the heart and specific kinds of inborn malfunctions. It was then when she also found that many children died, as a result of partial blockage of the pulmonary artery, either alone or combined with a hole between the ventricles of the infant’s heart.

Helen Taussig with a small patient in 1981. Photograph by permission of Tadder Associates.

The children who suffered from such inborn animally, usually also suffered from anoxemia, i.e., a malformation during which blood is not sufficiently being oxidized. Children with such defect either died soon or remained forever invalids. Due to the lack of oxygen, the skin in such youngsters characteristically turned blue, which was the reason why they were called ‘blue babies.’

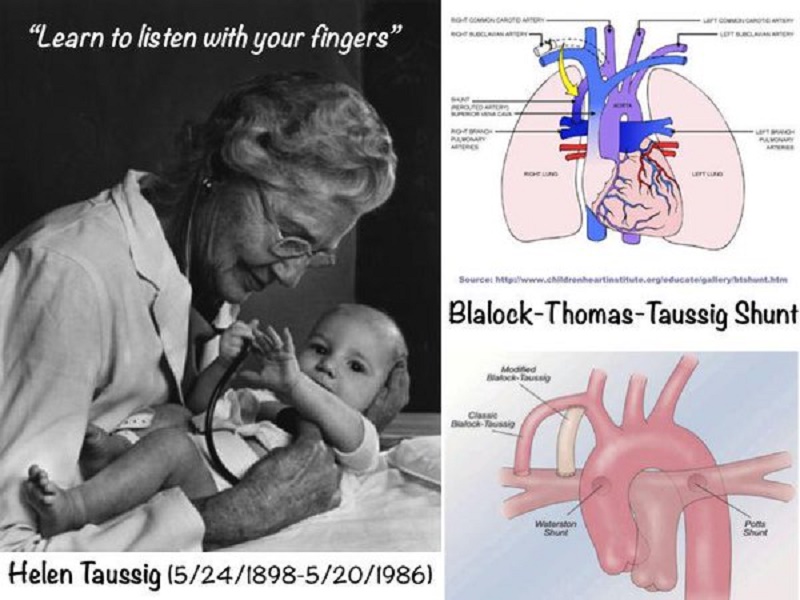

To prove her theory, Dr. Taussig joined forces with the university surgeon, Dr. Alfred Blalock, with whom she began experimenting, using experimental dogs. After hereafter they succeeded experimentally to reproduce the syndrome in dogs, they began working on a suitable surgical intervention, which would rectify the anomaly. The experiments were successful so that in 1944 first operation could be performed on a human patient – a 16-month child, suffering from this anomaly of a narrowed artery bringing the blood to the heart. With the surgical intervention, now known as the Blalock-Taussig Shunt, using an artery-like tube designed to deliver oxygen-rich blood from the lungs to the heart, they succeeded to bypass the narrowing of the artery. On November 29, 1944, Eileen Saxton, an infant affected by tetralogy of Fallot, a congenital heart disorder that gives rise to blue baby syndrome and that was previously considered untreatable, became the first patient to survive a successfully implanted Blalock-Taussig Shunt.

The clinical proof of the success of the surgical intervention, to correct anoxemia, was manifested by the lowering of the intensity of cyanosis, i.e., skin bluing and considerable improvement of dyspnoea, the shortness of breath, as well as the increase of tolerance to physical exertion. In 1946 four operations weekly were performed regularly on children with the faulty blood circulation, at the ages from three to twelve years of age. Physicians from all over the world were coming to view the course of these miraculous operations.

Dr. Taussig also played a major role in preventing a repetition in the United States of an epidemic of bizarre birth defects in Europe among babies born to mothers who took Thalidomide, a tranquilizer. Her investigation of the epidemic in West Germany helped warn American physicians of the hazard. She also testified before the US Congress about the harmful effects of the drug thalidomide.

Left, Jamie Wyeth’s 1963 portrait of Dr. Helen Brooke Taussig, and right, a more conventional 1981 likeness by the artist Patric Bauernschmidt. Source: NY Times.

Taussig was a prolific writer, publishing an astounding number of medical papers. In 1947 she wrote Congenital Malformations of the Heart, which was revised in 1960. Throughout her lifetime she received worldwide honors. She was awarded the Medal of Freedom by US. President Lyndon B. Johnson in 1964 and in 1965 Taussig became the first woman president of the American Heart Association.

In 1973, she was elected a member of the prestigious National Academy of Sciences. That was an extraordinary honor, considering that the Academy had only a handful women among its midst and, moreover, that only a very small number of physicians achieved such distinction.

Helen Brooke Taussig died during an automobile accident in Philadelphia on May 21, 1986, at the age of 88. As was characteristic of her, in her last will she donated her mortal remains to university hospital for the purpose of scientific research.

Sources: Medical Archives 1, Medial Archives 2, CF Medicine, NY Times.

Guest Post Author

Mila Rechcígl

Miloslav Rechcígl, Jr. is one of the founders and past Presidents of many years of the Czechoslovak Society of Arts and Sciences (SVU), an international professional organization based in Washington, DC. He is a native of Mladá Boleslav, Czechoslovakia, who has lived in the US since 1950.

Read his entire profile here. Discover Mila’s many books on Amazon.

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Become a friend and get our lovely Czech postcard pack.