Today marks the anniversary of the death of Jan Palach and in his honor, we are sharing a film we recently watched about him and what he means to the people of the Czech Republic.

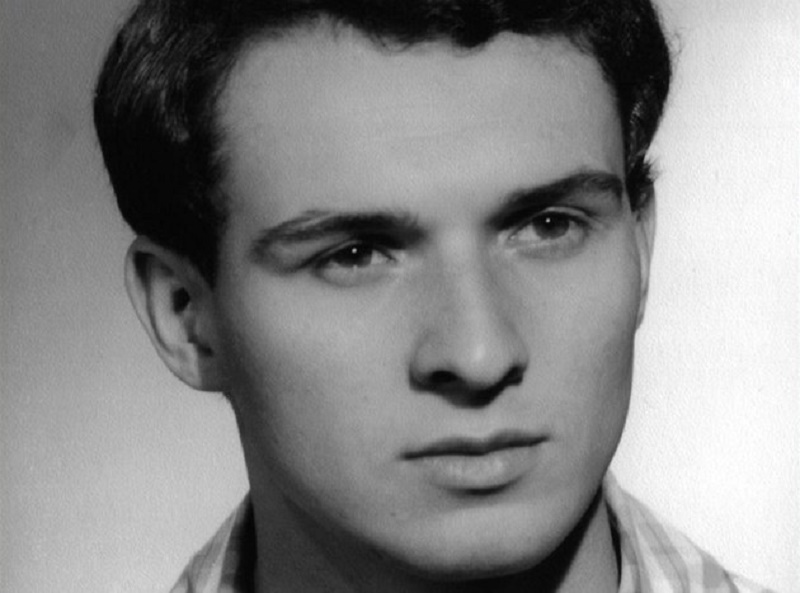

In January 1969, Czechoslovakia was under Soviet occupation following an August invasion to crush the liberal reforms of Alexander Dubcek’s government. Five months after the Soviet invasion of Czechoslovakia on January 16, with the intent to stir a Prague on the “edge of hopelessness,” Jan Palach, an earnest 20-year old university student staged a dramatic protest of Soviet repression and occupation.

“Entering Wenceslas Square in the bustle of mid-afternoon traffic, Palach carefully removed his overcoat, poured a small can of gasoline over himself and struck a match,” wrote Time.

“Instantly, to the horror of several dozen passersby, he turned into a human torch.”

“Despite a bus dispatcher’s frantic effort to smother the flames with his overcoat, Palach’s body was ravaged. He died three days later.”

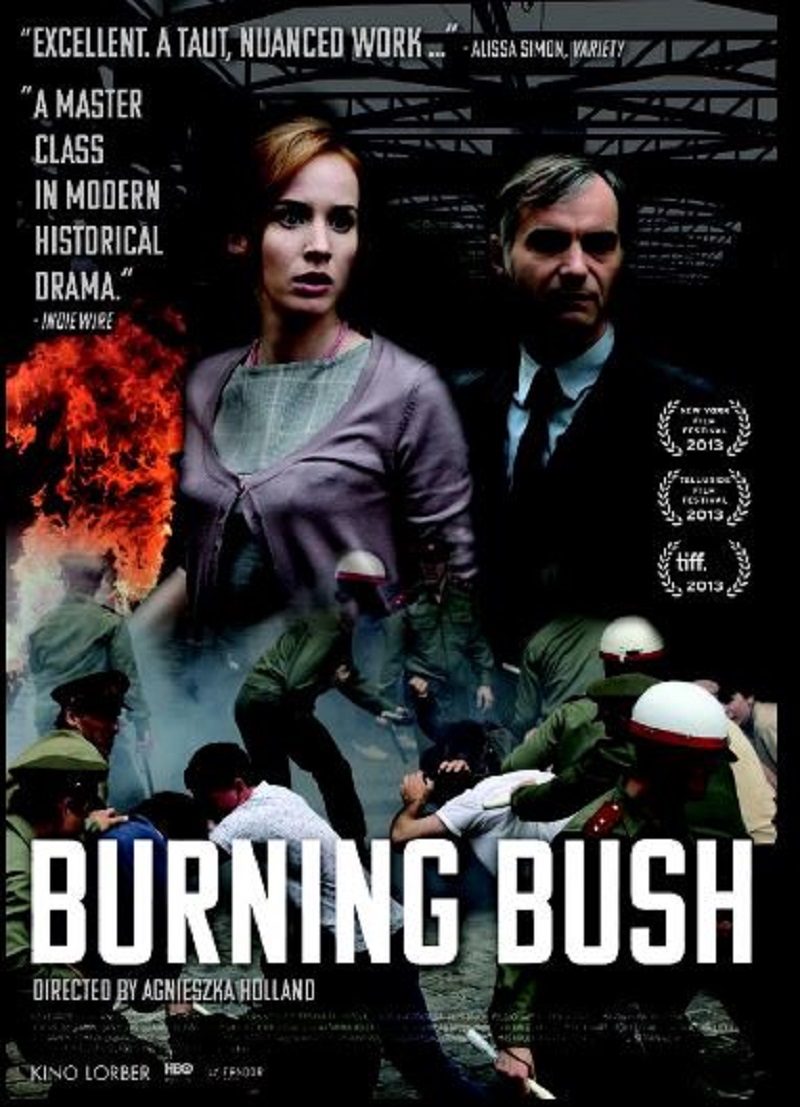

This is the beginning scene from a 2013 HBO mini-series which is now on DVD called Burning Bush (Hořící keř).

Watching a man ignite himself into flames is a disturbing sight, as we see in the first few moments of the film. But we watch anyway. Drawn to how a single match can ignite a nation.

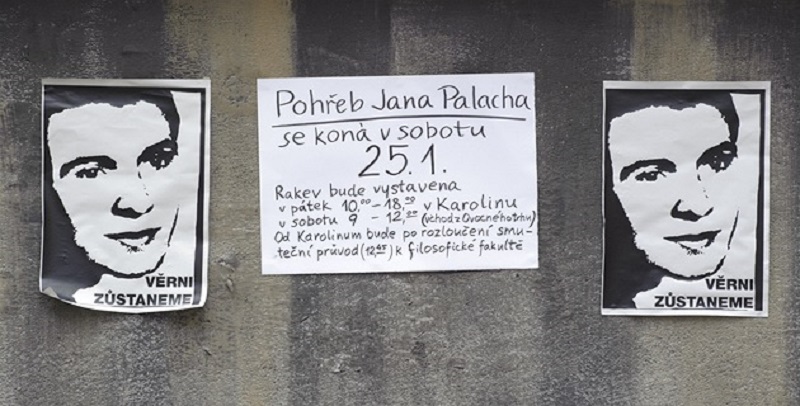

Jan Palach committed suicide by self-immolation in Prague’s Wenceslas Square.

He sacrificed his life to re-awaken opposition to the Soviet occupation of 1968, and eventually become a galvanizing symbol of the Velvet Revolution.

Burning Bush is not simply an artful historical drama that tells a story, but a moving and poignant work of art which unveils layer after layer of human emotion and response. This is due to the masterful way the film’s plot takes up several strands of narrative that are ultimately woven together to tell this important piece of Czech history.

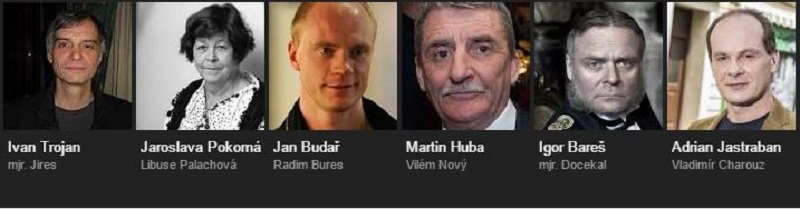

The cast seems as though they were born to play each part in this intelligent political panorama with a wide scope and a beautifully wounded heart.

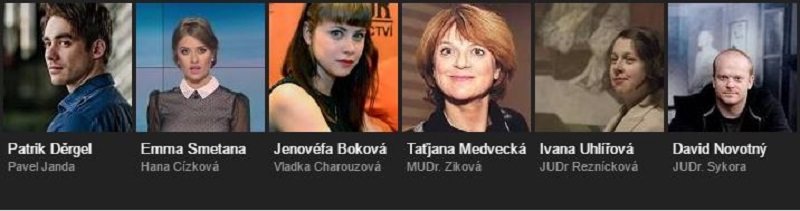

Though the story is about Jan Palach, it’s Dagmar Burešová whose perspective dominates. She is brilliantly portrayed by the lovely Tatiana Pauhofová, a Slovak actress born in Bratislava.

In part one, we are shown us the chaos and how it spreads to every corner of Prague.

We learn that according to a note in Palach’s coat, he hoped for an end to censorship of the Czech press and a ban on the Soviet newspaper, Zpravy, a propaganda newspaper for the occupying armies. It also called for a general strike. If these demands are not met within five days, the letter states, more self-immolations will follow. The letter is signed, Torch Number One.

Dr. Jaroslava Moserová, the plastic surgeon who treated Palach for burns at the hospital, told Radio Prague, “When people say that he did it because of the invasion of the Warsaw Pact armies, that’s not really so. He did it because of the demoralization that was setting in.”

Dr. Jaroslava Moserová, the plastic surgeon who treated Palach for burns at the hospital, told Radio Prague, “When people say that he did it because of the invasion of the Warsaw Pact armies, that’s not really so. He did it because of the demoralization that was setting in.”

Having left multiple letters of protest, there was no question why Palach did what he did.

Certain events in the film have been simplified and compressed for clarity and concision (the court case, for example), but what happens in these early scenes and in much of the film is a matter of historical record.

Polish filmmaker, Agnieszka Holland, happened to be studying in the then Czechoslovakia when Palach self-immolated on Wenceslas Square. She shared the feelings of inspiration, frustration, and rage that swept across the country in the days that followed. Now she masterfully captures the tenor of those oppressive times in the monumental Burning Bush.

As Jan Palach hoped, the student movement is emboldened to call for a general strike.

The government swings into full panic mode, fearing more will follow his example.

The Party’s heavy-handed techniques do not sit well with Police Major Jireš, but his ostensive subordinate is more than willing to do the dirty work he assumes will advance his career.

Part two takes the form of a conspiracy thriller. Jan Palach’s mother decides to hire a young attorney, Dagmar Burešová, and sets her mind to sueing a party official for slandering her son in print.

“There are at least a dozen stellar actors in the film, but perhaps the most spectacular is Jaroslava Pokorná as Mrs. Palachová, whose shock and sorrow transform her into a mythic figure: part doughy-faced babushka, part Mater Dolorosa…”

“Every artistic choice Pokorná makes, every emotion conveyed in the stance of her thick-set body and fleeting across her mobile, expressive features reminds us there was a real Mrs. Palachová, who—like her onscreen counterpart—was so determined to defend her beloved son against the lies that were told about him after his death that she took the extraordinary step of suing, in court, a member of Parliament and a prominent Communist Party member….”

Pokorná as Palach’s mother is not merely a performance, it is an indictment viewers will feel down to their bones. She delivers a heartbreaking and harrowing portrayal of a woman nearly broken by the Communist state.

“The fact that she was not a political radical but rather an ordinary Czech citizen whose son had been wronged made her action all the more powerful—and more threatening to the authorities.” – Francine Prose

In response, the collaborationist Czech government intimidates Mrs. Palach, Burešová and her family and as the months begin to pass, the fragile mother of Palach becomes the target of a ruthless harassment campaign.

Eventually, Dagmar Burešová agrees to take the case, but it will cost her family dearly.

Then we begin to see the working of standing against a repressive regime.

Her husband suffers in his position and eventually loses his job, and she is constantly followed and watched.

This was a master mini series which originally aired as three episodes. We watched the DVD and saw straight through the entire production, almost 4 thrilling hours.

Although Palach appears relatively briefly in Burning Bush, his absence is felt keenly throughout. He is the missing man—the ghost at the banquet.

However, his mother and her advocate are very much of and in the world as it was, and must carry on as best they can.

Part three is a courtroom drama as Burešová finally gets the case to trial and we finally see Vilém Nový, the communist official who defames Palach, in court.

We also witness Burešová and her assistant thrown into disarray as their leads start to dry up.

We also witness Burešová and her assistant thrown into disarray as their leads start to dry up.

Of course, this is due to coercion and sabotage by the party.

Burning Bush will be nothing less than revelatory for many viewers.

Typically films dealing with the Prague Spring and subsequent Soviet invasion end in 1968, with a happier 1989 postscript frequently appended to the end. However, Holland and screenwriter Štĕpán Hulík train their focus on the nation’s absolutely darkest days.

There is considerable scale to Burning Bush, but it is intimately engrossing. Viewers acutely share the fear and pain of the Palach family and marvel the Bureš family’s matter-of-fact defiance.

Somehow Holland simultaneous builds the suspense, as Burešová methodically exposes the Party’s lies and deceits, as well as a mounting sense of high tragedy, as the secret police rig the system against her.

Petr Stach conveys all the inner conflicts roiling inside Jiří Palach, the brother forced to hold himself together for the sake of his family (and arguably his country).

Ivan Trojan’s increasingly disillusioned Major Jireš adds further depth and dimension to the film.

Tatiana Pauhofová has some very impressive moments as Burešová, particularly with Jan Budař as her husband Radim Bureš.

One of the film’s most devastating shots goes literally through a wall to reveal a gang of operatives listening to a conversation, deciding ahead of time how it will end.

Yes… Deciding the outcome of the court we were just witness to.

Segments of archival footage are interspersed throughout and the focus is clearly that there is a great hardship that comes with being on the right side of history, but that we also have to choose to live by a right moral code, not matter the sacrifice.

Chosen by the Czech Republic as its official foreign language submission to the Academy Awards, but disqualified because it was originally produced for Czech HBO, Burning Bush is both excellent cinema and outstanding television (finally), depending on how chose to categorize it.

And although the four hour (234 minute) running time might sound intimidating, it is a blisteringly tight and tense viewing experience. which we highly recommend.

At the end of the film, we are reminded that, twenty years after his death…

Jan Palach again became a powerful symbol when the Czechs rose up against the Communist government in 1989.

Later that year, Dagmar Burešová, coincidentally born under the sign of the scales of justice, and the attorney who spent her life representing dissident opposition leaders, would also be vindicated by becoming Minister of Justice of the first post-Communist administration.

The real Dagmar Burešová.

The film is dedicated to Jan Palach, Jan Zajíc, Evžen Plocek, Ryszard Siwiec and to all who sacrificed their lives while fighting for freedom.

At 3 hours and 51 minutes, make sure you have ample time to settle in and watch the entire film. We sat in on a rainy day and watched straight through.

Watch the full-length international trailer:

An important and deeply moving work, Burning Bush has its focus on everyday citizens, it kindles and then fans a flickering hope for the masses of individuals down and out, waiting and wanting to rise up, consumed not by hate or fear but a desire for a fairer system and better lives.

You can purchase the DVD on Amazon, Barnes & Noble or eBay or stream part one and part two on Amazon.

If in Prague…

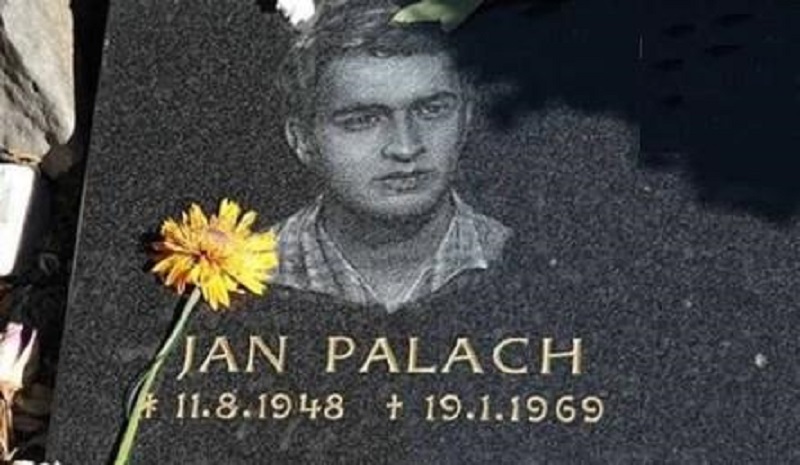

Jan Palach Memorial.

We located footage of the funeral from British television. You can view that below.

Learn more about Jan Palach through a multimedia project by the Charles University here.

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Become a friend and get our lovely Czech postcard pack.