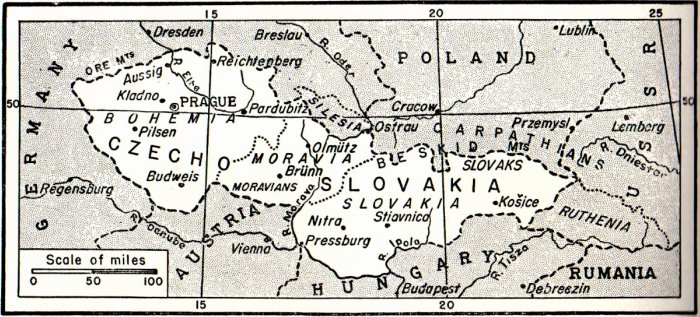

Today I wanted to share a look back at Czechoslovakia before World War I. The first image I want to share is this map.

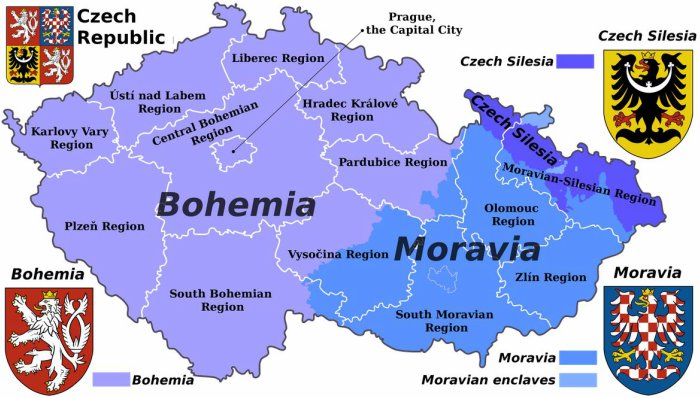

When the Czech Republic was first put on a map, it was placed there as Czechoslovakia. The Bohemian Kingdom officially ceased to exist in 1918 by transformation into Czechoslovakia.

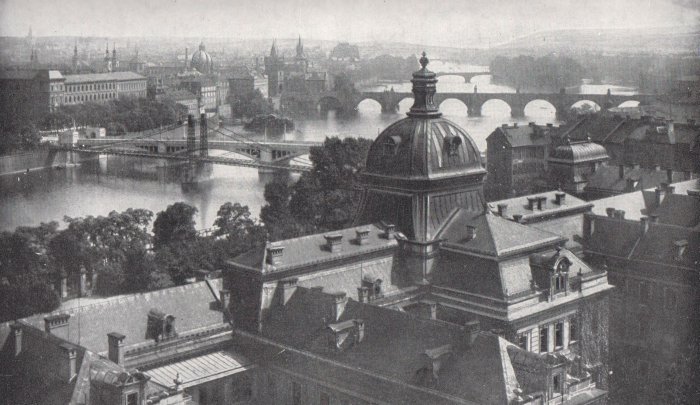

No one is completely clear on the origins of the Czech people, but they were a tribal group that settled in central Europe about 500 ad. They had an association with the Boii tribe, after which the area of Bohemia takes its name, and they were closely related to the Slavic people who settled in the same area about the same time. They were associated with the Great Moravian Empire of the 800’s and then with the Bohemian Empire that followed in the 900’s. Bohemia grew to be quite large and was a self-governing state of the Holy Roman Empire during the Middle Ages. Prague was the empire’s leading city.

But the location on the map and borders just kept changing…

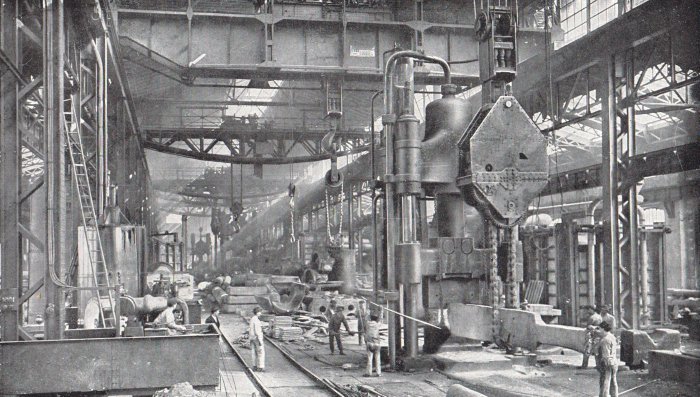

Czechoslovakia was officially founded in October of 1918, as one of the successor states of Austro-Hungarian Empire at the end of World War I and as part of the Treaty of St. Germain. It consisted of the present day territories of Bohemia, Moravia, Slovakia and Carpathian Ruthenia and its territory included some of the most industrialized regions of the former Austria-Hungary.

The area was long a part of the Austro Hungarian Empire until the Empire collapsed at the end of World War I. The new state was founded by Tomáš Garrigue Masaryk (1850–1937), who served as its first president from November 14, 1918 to December 14, 1935. He was succeeded by his close ally, Edvard Beneš (1884–1948).

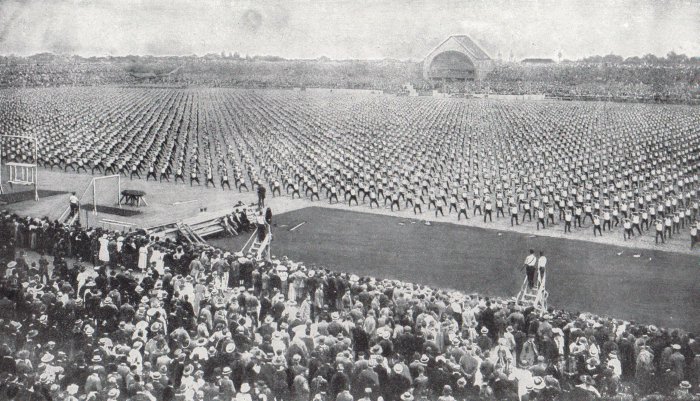

The roots of Czech nationalism go back to the 19th century, when philologists and educators, influenced by Romanticism, promoted the Czech language and pride in the Czech people.

Nationalism became a mass movement in the last half of the 19th century.

Taking advantage of the opportunities for limited participation in political life available under the Austrian rule, Czech leaders such as historian František Palacký (1798–1876) founded many patriotic, self-help organizations which provided a chance for many of their compatriots to participate in communal life prior to independence.

Palacký supported Austroslavism and worked for a reorganized and federal Austrian Empire, which would protect the Slavic speaking peoples of Central European against Russian and German threats.

An advocate of democratic reform and Czech autonomy within Austria-Hungary, Masaryk was elected twice to Reichsrat (Austrian Parliament), the first time being from 1891 to 1893 in the Young Czech Party and again from 1907 to 1914 in the Czech Realist Party, which he founded in 1889 with Karel Kramář and Josef Kaizl.

During World War I small numbers of Czechs, the Czechoslovak Legions, fought with the Allies in France and Italy, while large numbers deserted to Russia, in exchange for their support for the independence of Czechoslovakia from the Austrian Empire.

With the outbreak of World War I, Masaryk began working for Czech independence in union with Slovakia. With Edvard Beneš and Milan Rastislav Štefánik, Masaryk visited several Western countries and won support from influential publicists.

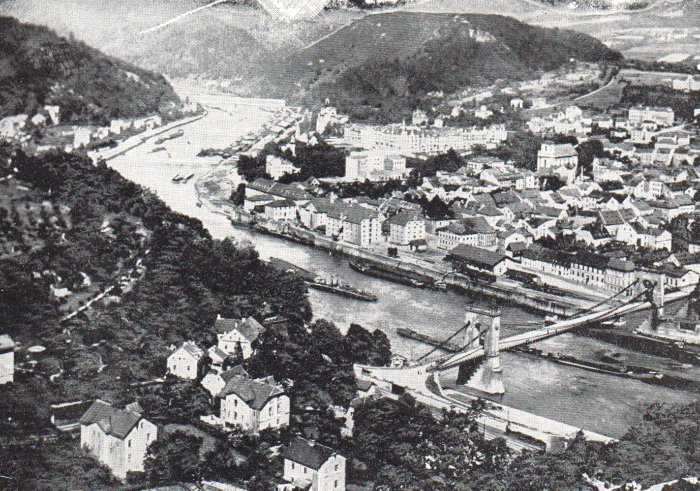

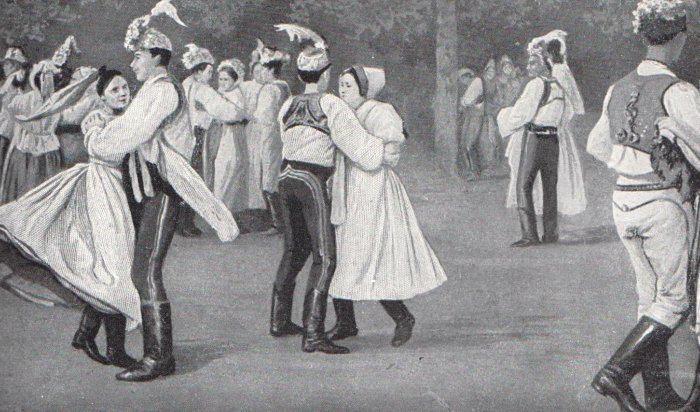

Bohemia and Moravia, under Austrian rule, were Czech-speaking industrial centres, while Slovakia, which was part of Hungary, was an undeveloped agrarian region. Conditions were much better for the development of a mass national movement in the Czech lands than in Slovakia. Nevertheless, the two regions united and created a new nation. Keep in mind, also that Moravia was in the center of the two. Czechs (Bohemians), Moravians and Slovaks all speak a similar Slavic language but have a very different dialect.

The girls above are wearing Czechoslovakian national folk dress. It included lots of embroidery and reds, blues and golds.

Even the ribbons of her cap are richly embroidered. The women of Czechoslovakia loved to wear their national finery and were proud of their handwork. Lots of gold thread was used in both Bohemian and Slovak Kroje.

A very well preserved photograph of a group of Bohemian girls wearing national folk dresses from 1892.

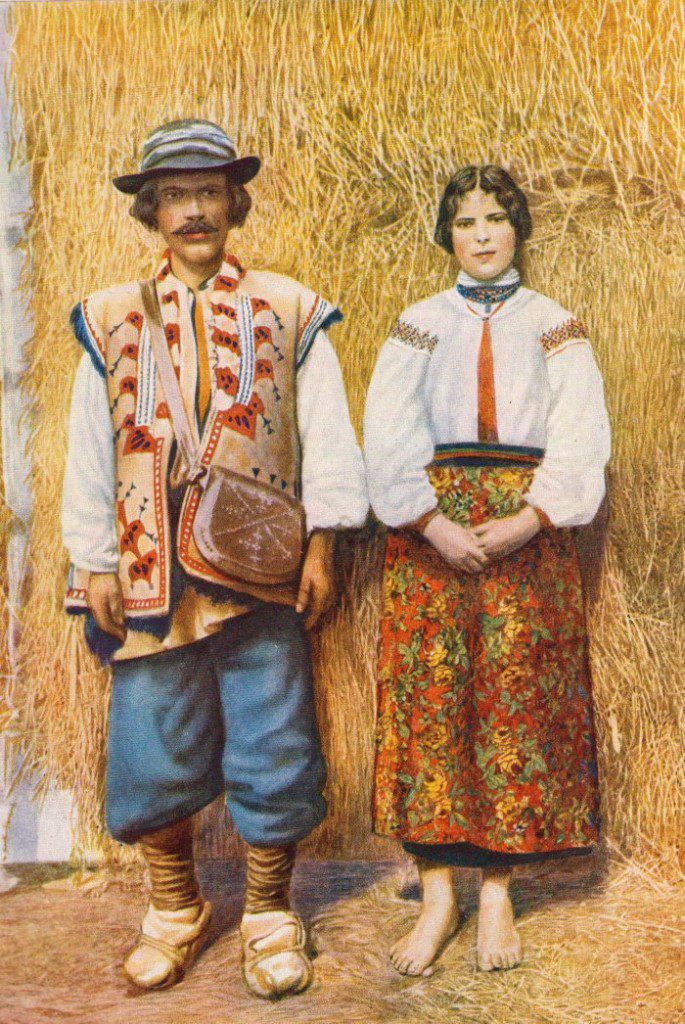

Kroje (pronounced “kro-yeh”, singular: kroj) are folk costumes worn by Czechs, Moravians and Slovaks. Gothic influence is seen in tying shawls and kerchiefs on the head.

Fine pleats and gathered lace collars typify the Renaissance era. From Baroque bell-shaped skirts to delicate Slavic patterns, their traditional folk costumes show Czech, Moravian and Slovak traditions.

Holiday clothing is brightly colored and heavily embroidered. Note the matching tall black leather boots on both mother and daughter.

Girls in traditional folk clothing, playing.

Note the bridal ribbon headdress. Brides in Slovakia did not wear white. Instead, they wore a crown of as many colors as they could composed of many, many ribbons.

Another image of a Slovak bride, this one is from 1953. The bride from a village known as Očová, in the Podpoľanie region of Central Slovakia.

A couple from 1890 wearing traditional folk dress.

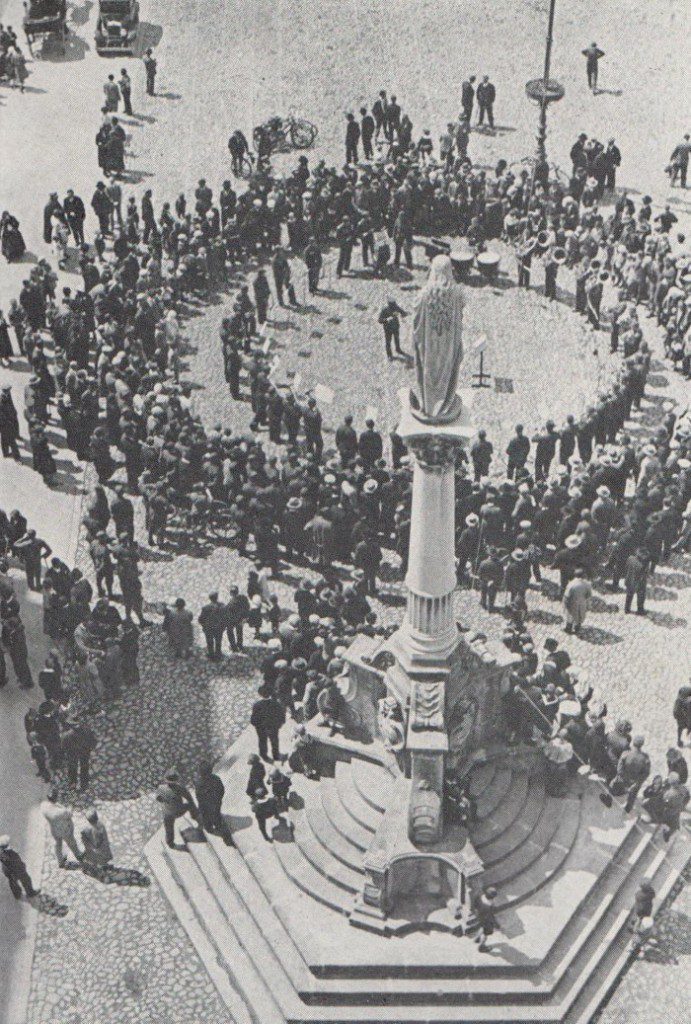

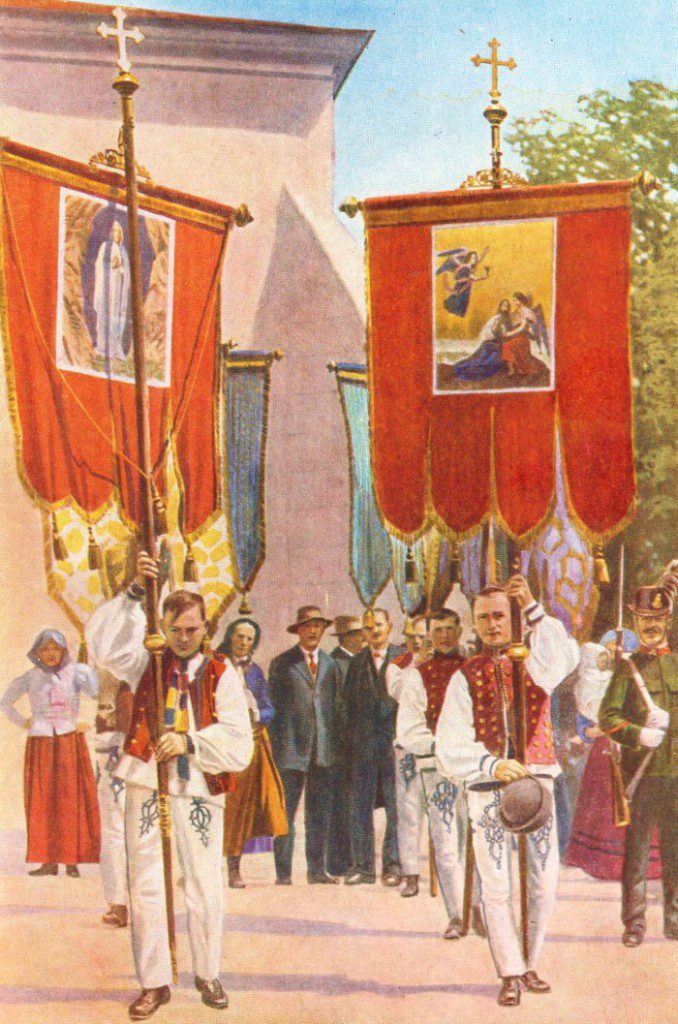

Men also dressed up. In the photo below, a group of Slovak men march with colorful banners celebrating the name day of their patron saint.

Detail of a traditional folk dress from Moravia on woman praying.

Even Slovak peasant women cared to wear a Kroj.

Even Slovak peasant women cared to wear a Kroj.

Czech dolls, dressed in national folk dresses.

Pan Tichy in traditional national male folk dress or Kroj. Estimated date, 1920.

And while Prague was much more ‘western’ in their clothing at the time, people in Prague did still pull out the traditional folk dress during certain festivals and celebrations.

Slovak men wore trousers that resembled large skirts. You can even see the little boys wearing them.

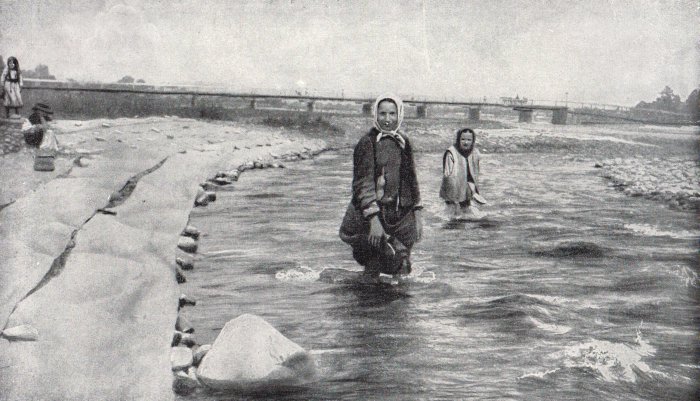

Hemp fields were plentiful and many clothes items were made from this sturdy fabric which was rather simple to work with. The Slovakian women below are wearing clothing made from hemp.

Entire families worked with the plant.

And so many of the earlier textiles in the area were made from hemp (konopĕ).

Czechs are predominantly Roman Catholic and especially the peasant people practiced their religion. Below is a small shrine between villages.

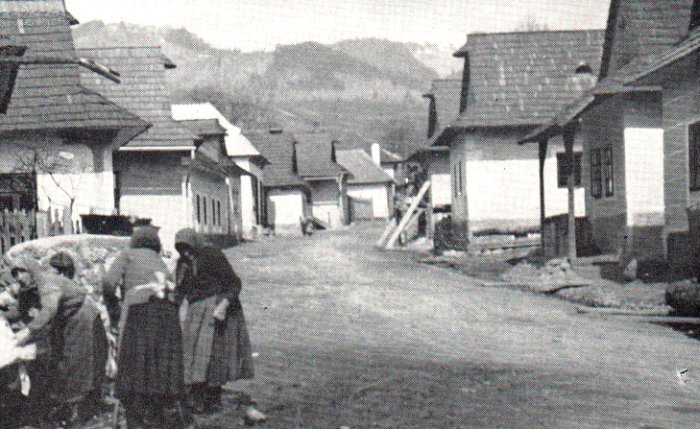

You will not find too many farmhouses standing alone in Czechoslovakia. Instead, they huddled them together forming little hamlets. The homes were simple but very comfortable and always had a high pitched roof to ensure that the snow would fall off easily. Both men and women worked in the fields and took their sheep or cows to the foot of the hills for green grasses. Whenever there was a festival, such little hamlets would come to life with folk costumes, song, feasting and merriment.

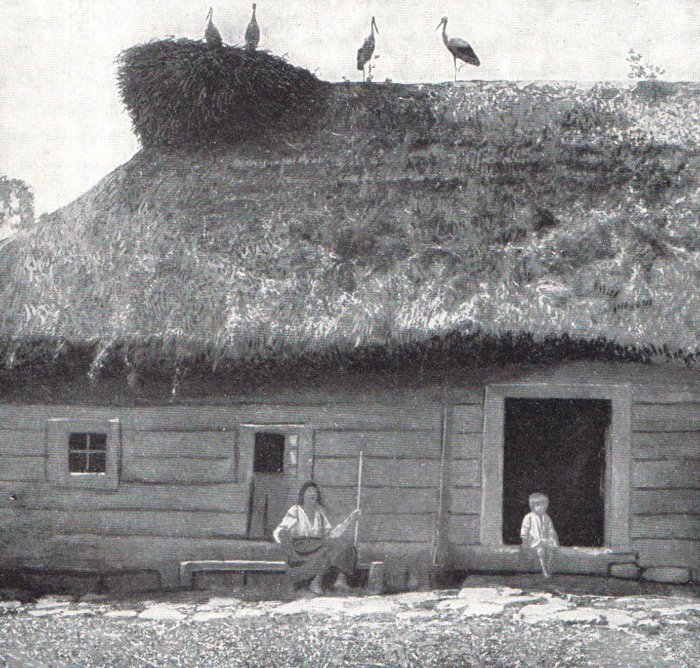

Slovaks had even more rustic homes, and yet when a stork nested on the roof – it was an incredible blessing and considered a very lucky omen, especially for Ruthenians. You can see the bundles of flax and hemp drying on the roof.

You may have noticed that the map at the top also shows Ruthenia, on the far eastern end of the country. Because it was at one time a part of Czechoslovakia, I have decided to include it here. The area has always been populated by Carpatho-Ruthenians, a group of East Slavic highlanders. While Galician Ruthenians considered themselves to be Ukrainians, the Carpatho-Ruthenians were the last East Slavic people that kept the ancient historic name (Ruthen is a Latin deformation of the Slavic rusyn). Nowadays, the term Rusyn is used to describe the ethnicity and language of Ruthenians who did not embrace the Ukrainian national identity. In May 1919, the area was incorporated with nominal autonomy into Czechoslovakia.

After this date, Ruthenian people have been divided among three orientations. First, there were the Russophiles, who saw Ruthenians as part of the Russian nation; second, there were the Ukrainophiles who, like their Galician counterparts across the Carpathian mountains, considered Ruthenians part of the Ukrainian nation; and, lastly, there were Ruthenophiles, who said that Carpatho-Ruthenians were a separate nation, and who wanted to develop a native Rusyn language and culture.

On 15 March 1939, the Ukrainophile president of Carpatho-Ruthenia, Avhustyn Voloshyn, declared its independence as Carpatho-Ukraine. On the same day Hungarian Army regular troops started to occupy the new state. The Hungarian occupation regime was pro-Ruthenophile.

In 1944 the Soviet Army occupied Carpatho-Ruthenia, and in 1946, annexed it to the Ukrainian SSR. Officially, there were no Rusyns in the USSR. In fact, Soviet and some modern Ukrainian politicians, as well as Ukrainian government claim that Rusyns are part of the Ukrainian nation. Nowadays the majority of the population in the Zakarpattya oblast of Ukraine consider themselves Ukrainians, however, a small Rusyn minority is still present.

A Rusyn minority that remained after World War II in northeastern Czechoslovakia (now Slovakia). According to critics, the Ruthenians rapidly became Slovakisized. In 1995 the Ruthenian written language became standardized. They’re included here so they do not completely disappear…

The images above are all from my edition of Land and Peoples: The World in Color, Volume II, published by the Grolier Society in 1929, 1930, 1932 and 1949 by The Grolier Society Inc. Other sources: Wikipedia, Catholic Encyclopedia 1913, Wikipedia, Girl in 1909, 1890 Bridal Couple, Bohemian girls 1892, Pan Tichy, Woman praying, Bride from 1953.

We tirelessly gather and curate valuable information that could take you hours, days, or even months to find elsewhere. Our mission is to simplify your access to the best of our heritage. If you appreciate our efforts, please consider donating to support this site’s operational costs.

See My Exclusive Content and Follow Me on Patreon

You can also send cash, checks, money orders, or support by buying Kytka’s books.

Your contribution sustains us and allows us to continue sharing our rich cultural heritage.

Remember, your donations are our lifeline.

If you haven’t already, subscribe to TresBohemes.com below to receive our newsletter directly in your inbox and never miss out.

Very nice.