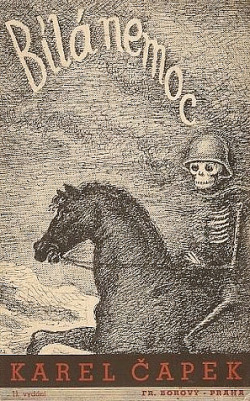

A virus that first appeared in China, spread by shaking hands, putting the elderly at risk. The Czechoslovak film The White Disease (1937) evokes current headlines, but uses the epidemic primarily as a perspective on war and dictatorship. Bílá nemoc (The White Disease – as in leprosy) is a play written by Czech novelist Karel Čapek in 1937.

Written at a time of increasing threat from Nazi Germany to Czechoslovakia, it portrays a human response to a tense, prewar situation in an unnamed country that greatly resembles Germany with one extra addition: an incurable ‘white disease’, a form of leprosy, is selectively killing off people older than 50 years of age. The White Disease aka Bílá Nemoc was also known more colorfully as Skeleton on Horseback.

I thought this was a fascinating historical document. It is an anti-fascist Czechoslovak film released a year before the Munich Agreement and two years before total Nazi occupation in Czechoslovakia. Viewing this today, however, it’s perhaps even more arresting as a picture of belligerent governance during a pandemic.

Bílá Nemoc was remarkable for sounding the alarm relatively early on the dangers of fascist nationalism in Europe in the 1930s. It would be three years even before Charlie Chaplin made The Great Dictator (1940), for instance, which was still an early anti-Nazi film to come from Hollywood.

Unfortunately, it’s message on the dangerous interactions of the contagions of politics and disease have hardly been heeded in the 84 years since, either. This is why we recommend a viewing of The White Disease (aka Bílá Nemoc).

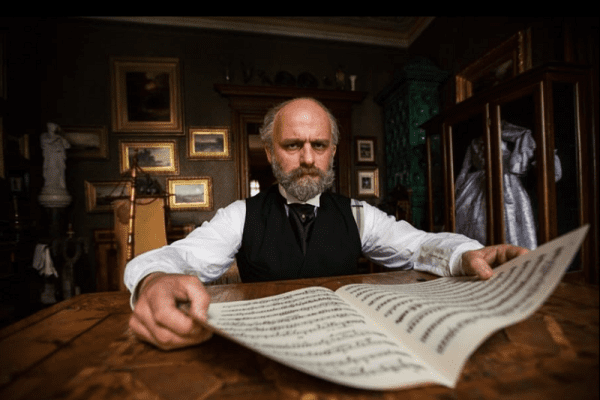

In an unnamed country (which is led by a warmongering Marshal) a disease, which only affects the over 50s, begins to spread. While the government-financed clinics fail to find an answer, backstreet GP Dr. Galen (played by Haas) discovers a cure.

After proving the cure’s authenticity, Dr. Galen informs the press that he will treat the poor immediately but will only treat the rich if the Marshall, who is about to declare war on a neighboring country, signs a peace treaty. Naturally, the Marshal refuses to accept the conditions and sends his men to bring the good doctor to him.

Although obviously an anti-war film (released just a couple of years before WWII), the characters in The White Disease are not simply black and white. Dr. Galen, who is a pacifist, actually stands by and lets people die to stand by his threat. The Marshal on the other hand, doesn’t act as ruthless as you may expect – for instance he never threatens to torture Galen to obtain the cure and actually does eventually release him. Both characters are given interesting, believable background stories and justifications for their very different outlooks on life.

One might ask, what is an epidemic doing in a film about fascist aggression? The answer lies in the relationship between the two death machines. At the beginning of the film they run parallel to each other: the war is approaching, the epidemic cannot be stopped. They are ultimately related to one another by the doctor. Doctor Galen (Haas, a tragically sad man of pain) has found a remedy for the disease, but he only administers it to the poorest of the poor, and refuses to use it on a massive scale in the country’s hospitals – as long as the war preparations continue.

Galen refuses to accept a trade-off that would result in making the people fit for death. This twist ensures that the epidemic cannot be reduced to a political allegory. It is not a mere equivalent of war (and it is not just a question of characterizing fascism as an epidemic), rather it is interesting precisely in its difference to war. The plague unmasked death, stripped it of heroism. Suddenly it is no longer a collective national fate, but affects single, weak individuals. Also the dictator’s immediate circle and finally, as expected, himself. The film finds its center in the encounters between Galen and the ruler.

The White Disease manifests itself as a stain on the affected area of the body; cold and insensitive at first, then the meat rots and falls off. It is a disease similar to leprosy, but it is not leprosy, since it has only recently appeared in the world, and there is no cure or vaccine.

Doctors have named her “Morbus Chengi,” because Dr. Cheng was the first to describe her in a Pei-Pin hospital. It soon becomes a pandemic that kills, above all, adults between 45 and 50 years of age and the only way to “cope” with the ineffectiveness of any other method is rather medieval, using chemical agents to eliminate the pestilence.

At the same time, as in the novel In the days of the comet by HG Wells, faced with the impending catastrophe, the world is preparing for another war. The dictator, the Marshal (Zdenek Stepánek), describes his young soldiers as “beautiful and brave”, and the accident in a chemical plant, due to the escape of a novel weapon, the “C gas “, Leaves several fatalities, of whom condolences are given to their relatives but before whose tragedy the politicians consider a” successful test “of the gas), since the dictator on duty, claims” space for his nation “, in an obvious allusion to the “living space” of the emerging Hitler.

This is opposed by Dr Galen (the same Hugo Hass, director of the film), originally from Pergamum, Greece (hence his name, in homage to the first doctor in history), apparently the only sane person in that country , and that he claims to have discovered the cure. He goes to the cold Professor Sigelius (Bedrich Karen), but he doubts him at first; later, Faced with the scientific advances of Galen, it will be Sigelius who, during a visit from the Marshal, takes the credit and ends up decorated. In an oversight, Galen turns to journalists, whom he confesses to be, really, who discovered the cure, and who he entrusts to announce from the rooftops that, unless the leaders of the world, all in the age of contracting the disease, wars cease, he will not give you medicine.

Galen is expelled from the hospital, as Sigelius considers his “plague of pacifism” more harmful than the plague.

During a conversation between Baron Krog, the owner of factories of war material and Sigelius, the latter proposes to send all the sick to concentration camps (the citizens are so distracted by the smoke screen of war, that ignore the risks of the pandemic), but the baron uncovers his chest, before the astonished eyes of Sigelius, who recognizes the signs of the plague, but has thrown Galen out of the facilities, and he is dedicated to vaccinating only the poor. The next on the list is the dictator himself, who gets sick when he shakes hands with Krog, because “he is a strong man without fear.”

Thus, the plague manifests itself in this scenario under a double form, that of disease, and that of politics, which leads to total war. By the time the murderous marshal in charge of the war machine sees the white spots on his own skin and realizes he’s done for, his deathbed agreement to lay down arms is too late to save him from the epidemic.

The ending, though predictable — the fanatics lynching Galen, before he can help the dictator, when he orders a cessation of hostilities — is still naive, but it is charged with emotion.

The White Disease is based on the play by Czech author Karel Čapek, the same one who gave the world the word “Robot”, and one of the few representatives of science fiction literature who wrote from dramaturgy.

You can watch the entire film here:

(I’m sorry, I could not find one with English subtitles.)

The emotional tenor of the situations comes across very strongly indeed and it makes you able to appreciate both the strong anti-fascist nature of the movie and the chilling irony of the ending of the movie.

Apparently, The White Disease (aka Bílá Nemoc) was the last movie made in Czechoslovakia before the Nazi invasion, and the movie was banned by the Nazis for its message. The film was smuggled to the United States by Hugo Haas himself and given distribution in this country by Carl Laemmle.

Hugo Haas would end up making a bunch of low-budget potboilers with Cleo Moore. Potboilers are overblown, trashy dramas in America in the 1950s, but back in the 1930s, he was a very well-respected actor/director/writer in Europe. Bílá nemoc is a classic example of the work that led to Haas’ high reputation, a thought-provoking, political and science fiction drama.

Janne Wass wrote, “Happy endings were not a trademark for Čapek, but The White Disease is still one of his most cynical works, almost completely devoid of the playful nihilism he displayed in so many of his other texts. And it is no surprise that the play, and likewise the film, feels like it is enshrouded in a blanket of resignation. Čapek had a disdain for collectivism in all forms, be it organized religion, communism or fascism, neither did he believe in corporate capitalism. But his most outspoken ideological stances throughout his life were his anti-fascism and his pacifism. Yet by 1937, he watched all his darkest nightmares coming true. In the East, Stalinism was quenching any of the hopeful optimism that might had existed in the young socialist federation, and in the West Hitler’s Nazi party loomed ever more dangerous, like a black plague spreading throughout Europe, now threatening to engulf his home country and thrust upon the world a war of catastrophic proportions. What’s more, for the pragmatic humanist Čapek, the coming war seemed devoid of reason or logic, a war that could benefit no-one but arms manufacturers and power-hungry despots. Yet, somehow, much of the world seemed oblivious to the utter folly behind the Nazi ideology, a world ruled by a content middle- and upper-class that somehow believed that they were impervious to the disease spreading through Europe.”

Thomas Mann wrote after Capek’s death: “If ever anyone died of a broken heart, he did”.

An intelligent film which is charmingly naïve in many respects, is simply for asking for normality in a mad world. All in all, this is one Czech movie that deserves to be more widely known and seen, especially today. (I’m sorry, I could not find it with English subtitles.)

Foreword from the book by Karel Čapek (loosely translated by Google) The first impetus for this game years ago gave me the idea of a friend of the doctor Dr. Jiří Foustka: a doctor who discovers new rays, destroying malignant tumors, finds the rays of death in them; with their help he will become an autocrat and an unfortunate savior of the world. The idea of a doctor who, in a way, has the fate of humanity in his hands stuck to this theme. But in our time, there are so many people who have or want to have in their hands the destinies of nations or humanity that it would never tempt me to multiply them by another specimen if there was no other and more compelling stimulus: that is our time itself. One of the hallmarks of post-war humanity is a retreat from what is sometimes and contemptuously called humanity; which word includes pious respect for life and human rights, love for freedom and peace, the pursuit of truth and justice, and other moral postulates which have hitherto been considered the meaning of human development in the spirit of European traditions. As is well known, in some countries and nations a completely different spirit has emerged; not man, but class, state, nation, or race is the bearer of all rights and the only object of respect, but sovereign respect: there is nothing above him that would morally limit him in his will and rights. State, nation, regime is endowed with omnipotent authority; the individual, with his freedom of spirit and conscience, with his right to life, with his human self-determination, is physically and morally completely subordinate to the so-called collective, but essentially purely autocratic and violent order. In the present state of the world, simply, the spirit of political authority is in vivid conflict with the European tradition of moral and democratic humanity; this conflict takes place more and more threateningly in international affairs year after year, but at the same time it is an internal issue for every nation. True, today's world conflict can also be defined in terms of economic and social; or it can be interpreted in the biological terms of the struggle for life; but its most dramatic aspect is the collision of two great antagonistic ideals. On the one hand, the moral ideal of universal humanity, democratic freedom, world peace and respect for every human life and law. On the other hand, a dynamic anti-human ideal of power, domination, and national or other expansion, for which violence is a welcome tool and human life is only an instrument. In common terms, it is a conflict between the ideals of democracy and the ideals of unlimited and ambitious dictatorships. And it was this conflict in its tragic topicality that prompted the writing of the White Disease. It could be cancer or another disease instead of a fake "white disease"; but the author tried, as far as possible, to transfer the individual motives and the very localization of his play into the fictional sphere, so that it was not necessary to think of a real disease or of real states or regimes; moreover, he felt the leprosy somewhat symbolically, as a sign of the deep disruption of the white race; such an epidemic seems to man today as a return to the plagues of the Middle Ages. The author deliberately induced the whole dramatic situation of his conflict to the motive of a murderous epidemic; for a sick and poor person is compulsively and typically an object of humanity; his dependence on kind moral rules the deepest. Two great worldviews are intertwined here, so to speak, over a bed of pain, and in their conflict the life and death of leprosy is decided. He who represents the will to power will not be stopped on his way by compassion for human pain and horror; he who fights with him in the name of humanity and respect for life, refuses to help the suffering, because he himself fatally takes over the relentless morality of the struggle. Even in the name of peace and humanity, he will kill and die in hecatombs, if the dispute had to be fought once. In a world of war, Peace itself must be a tough and unyielding warrior. On the contrary, the representative of power and force himself becomes one of those who cry for human help, while the unstoppable machinery of the massacre that unleashed ruthlessly rolls over him. It was in this that the author saw the hopeless weight of the world conflict we are experiencing; it is not just that black and white, evil with good, injustice with law; high values and irreconcilable hardness collide on both sides; but what is at stake in this dispute is all good and right and all human life. In the end, it is only a crowd without greatness and compassion that will indifferently trample to death both representatives of opposing wills. Behold the humanity that humanity wanted to save, behold the crowds that the will to power wanted to lead to greatness and glory! Here you have your "all the people", Galen, here you have your nation, Marshal; and we all have our historical conflicts here, in which ultimate success is uncertain, but where only one thing is unquestionable: that Man will pay for them hard and painfully. Whatever the outcome of the war, the roaring of which concludes the White Disease, it is certain that Man remained unsaved in his suffering. The author is aware that this inevitable tragic conclusion is not the answer; but if it is a real struggle that takes place in our time and space between real human forces, we cannot solve it with words and we must leave its solution to history. Perhaps we can have confidence in the next people as well, such as the two honest and sensible young people at the end of the game; but the final solution remains a political and spiritual history in which we are engaged not only as spectators, but as comrades-in-arms, who must know on which side of the world dramatic conflict the whole law and the whole life of a small nation lie.

Sources: 1, 2, 3, 4, 5, 6, 7, and The Origins of Dread.

We know that you could spend hours, days, weeks and months finding some of this information yourselves – but at this website, we curate the best of what we find for you and place it easily and conveniently into one place. Please take a moment today to recognize our efforts and make a donation towards the operational costs of this site – your support keeps the site alive and keeps us searching for the best of our heritage to bring to you.

Remember, we rely solely on your donations to keep the project going.

Thank you in advance!

If you have not already subscribed to get TresBohemes.com delivered to your inbox, please use the form below now so you never miss another post.